When people began growing crops, they stored food by wrapping it with natural materials such as shells, gourds, animal skins, reeds, bark, and leaves. Eventually, people wove grasses and reeds into baskets. For thousands of years, this was all the packaging humans needed.

About 8,000 years ago, ancient people in the Middle East realized that they could benefit from storing their food in more durable, heavier containers. The first pots were simple balls of clay with holes carved into them, or long coils of clay molded into a round shape.

Glazing the pottery made it more durable. The glaze also kept water from seeping into the clay. Potters took pride in the pots they created, and had their own “mark” or pattern that they’d use to identify which pots were made by them.

Ancient Egyptians started using wood to make boxes for storing food. Wooden boxes were lighter, less fragile, and less cumbersome to move than pots. Two thousand years ago, people in Syria figured out how to blow glass and make the first glass containers.

Metal containers came next. Although silver and gold were used for cups, these were too valuable to use for food packaging. Tin was used instead. Later, inexpensive containers made from thin aluminum were used to package all kinds of food.

The next major innovation in food packaging was plastic. Plastic wrap, plastic containers, and Styrofoam all changed the way food was packaged and how long it lasted. Without proper packaging and storage, food will spoil and go to waste.

1310: First paper packaging in England.

1817: First cardboard boxes for packaging in England, 200 years after the Chinese invented cardboard.

1830: First metal boxes for packaging. Cookies, and then cakes, were sold in these.

1844: Rise of paper bags for packaging.

1900: Rise of glass bottles for packaging liquids.

1950: First aluminum foil containers for packaging. The first “TV dinners” were packaged on aluminum trays.

1950: Rise of aluminum cans for packaging.

1958: First plastic “shrink wrap” used for packaging.

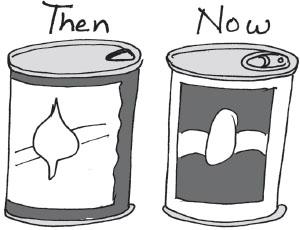

The metal food containers of the 1800s weren’t like the ones on your shelf today. Manufacturers sealed cans in a completely different way.

Cans were soldered together by hand. A small hole was left open on the top of the can. Food was crammed into this hole, which was then covered with a patch. But one tiny hole was left open. This hole let out steam while the food cooked right in the can. After cooking, the hole was sealed so no air could get into the can.

This canning method was so time-consuming that only about 60 cans could be made and filled in a day. After 1866, consumers used a “key” to roll a metal strip away from the side or top of the can, exposing the food inside. The can opener was invented in 1875, making this entire process a lot easier.

durable: able to last.

innovation: new idea or invention.

solder: to fuse metal together to form one piece.

complex carbohydrate: a food source such as whole grains or beans that gives you energy.

Until 1866, the only way to open a sealed can of food was to use a hammer and chisel!

Let’s say you’ve got a big soccer game coming up, and your coach has told you to eat a breakfast high in complex carbohydrates to give you enough energy for the game. You go to the store to shop for breakfast and turn down the cereal aisle.

A bright yellow box catches your eye. Mmmm … Fruity Bombs! You love the taste of fruit, you think the character on the box is cool, and there’s a sweet prize inside! You grab the Fruity Bombs and head home. But if you’d read the nutrition information on the side of the box, you’d realize there are zero complex carbohydrates in this sugar-filled bonanza in a box.

What just happened? You got caught up in the advertising. Manufacturers want packaging to do more than just hold their products. They want boxes that convince you to buy their product over everyone else’s.

Would you rather buy a plain brown box of spaghetti or a box with a photo of an amazing spaghetti meal, complete with steaming meatballs and freshly baked bread, on the front? When you’re in the store, remember that companies are trying to sell you their product. They spend a lot of money designing packaging to get your attention.

It’s important to know what you really need and want when you head to the store. If you buy the plain brown box of pasta, you could end up saving money—maybe enough to buy bread to go with your meal!

biodegradable: something that living organisms can break down.

organism: anything living.

bioplastics: plastic made from plant material.

non-renewable: energy sources that can be used up, that we can’t make more of, such as oil.

sustainable: a resource that cannot be used up, such as solar energy.

Paper and cardboard dominated the packaging industry for most of the last century. By the late 1970s, plastic became more popular.

Not using paper saves a lot of trees. But plastic doesn’t break down as easily as paper. This garbage has become a major problem for our environment.

Experts are coming up with new ways to reduce the environmental impact of packaging. They’ve developed biodegradable plastics with the starch from plants like corn, wheat, and potatoes. These bioplastics break down much more easily than traditional plastics. While traditional plastics are made from non-renewable oil resources, these bioplastics are made from renewable resources, so they’re much better for the planet.

Have you ever opened a box of cereal or crackers and found the plastic bag inside only half full? Companies designed this packaging hoping to give the impression there was more food.

You and your family can help the environment by making smarter food choices. Eat more fruits and vegetables that require no packaging (other than Mother Nature’s!) and food that has minimal packaging. You’ll probably be eating healthier, too!

A bottle can take around 1,000 years to break down. A paper bag takes just a couple of months.

In this activity, you’ll make a coil pot similar to the ones that our ancestors made to store their food. Don’t put any food in your pot, however, unless it’s in another wrapper. The clay you get at stores isn’t “food quality.”

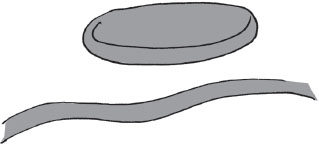

1 Begin by softening the clay. The heat of your hands will warm and soften the clay. Gently play with it, roll it around, and squish it. Roll a medium piece of clay into a ball and then press it flat until you get a circle about 3 inches in diameter. This will be the base of your pot.

2 Roll a large piece of clay into a long “snake.” The snake should be about a half inch in diameter.

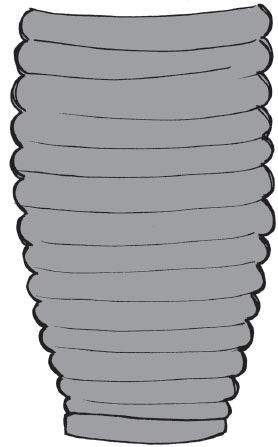

3 To build the sides of the pot, lay the end of the snake around the outside of the circle, coiling it up on top of itself to make a series of stacked rings. If you run out of snake before your pot is tall enough, just make another snake, attach it to the end where you stopped, and continue.

4 When your pot is the size you want, spray a little water on your coils and smooth them together to make the sides of your pot solid. Make sure to press the sides of your pot firmly into the base.

5 If you want to make a lid for your pot, roll another medium piece of clay into a ball and press it flat until it is the size of the top of your pot.

6 Dry your lid separately from your pot so they don’t stick together. Air-dry or bake your pot. When your pot is dry, you can decorate it with paint.

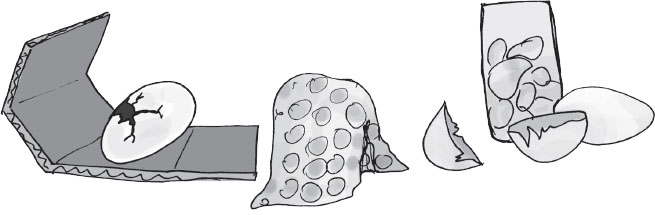

Manufacturers try to come up with packaging that will protect the food inside as it’s being shipped to stores. In this egg drop experiment, you’ll find out just how difficult it can be to keep food safe in transit!

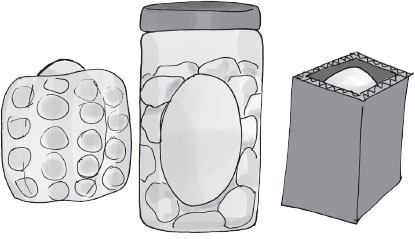

1 In this project, your goal is to create packaging that will protect an egg from a fall.

2 Think about the everyday materials that you have around the house. What might provide good protection for the egg? For example, you might consider cotton wool or leftover bubble wrap, or some kind of inner suspension in a plastic container.

3 Create several types of packaging for a few different eggs. That way, you can test to see which is most effective.

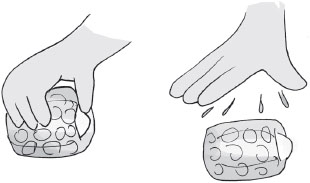

4 When your eggs are safe in their packaging, either drop them from a high place or throw them as high as you can—and get out of the way!

5 Carefully open up all the packages. Think about why some eggs survived and others didn’t. Then consider the packaging that real manufacturers use.

ASK YOURSELF:

Some food, like the crackers, needs protection from moisture that makes it go stale quickly. Other food, like the milk, loses vitamins when exposed to light for too long. And some food, like the potato chips, crushes easily and needs to be cushioned with air or a rigid tube. When you buy certain foods, you’re also paying for their special packaging!

Packaging not only has to protect food, but it also has to attract the consumer—you!—and make you want to buy the product. In this project, you’ll try to come up with your own eye-catching package.

1 Take your notepad to the grocery store. Walk up and down the aisles and look at the ways that companies present their products. How do they use color? Slogans? Characters? Who is the audience? Are they appealing to moms, kids, or both? Take notes on what you observe.

2 Then come home and look through your pantry. Pick a “boring” item that you’re going to market—plain saltine crackers, maybe, or spaghetti.

3 Think about how best to convince someone that he or she absolutely must have this product. How can you make it stand out from other products on the shelves? What are its major benefits? Convenience? Great taste? Versatility? Also, keep in mind the audience to whom you are trying to sell this product.

In commercials, only the food being advertised has to be real. The food around it can be fake to make it look good. The ice cream being sold might be real, but that whipped cream could be shaving cream!

4 Develop three different package designs. Apply each package design to a different box.

5 Show your packages to your parents, brothers, sisters, and friends, and ask them which one they’d be most likely to choose. Tally the results. The more input you get, the better.

6 When you’ve received all your feedback, go through the results. Every time companies develop a new product or redesign an old product, they go through this same process. Keep this in mind the next time that you go grocery shopping. When you buy a product, are you making your decision based on the packaging or the food inside? Could the generic store brand, with the same taste at a lower price in less attractive packaging, be a better choice?