CHAPTER TWO

Nome

June 6, 1900

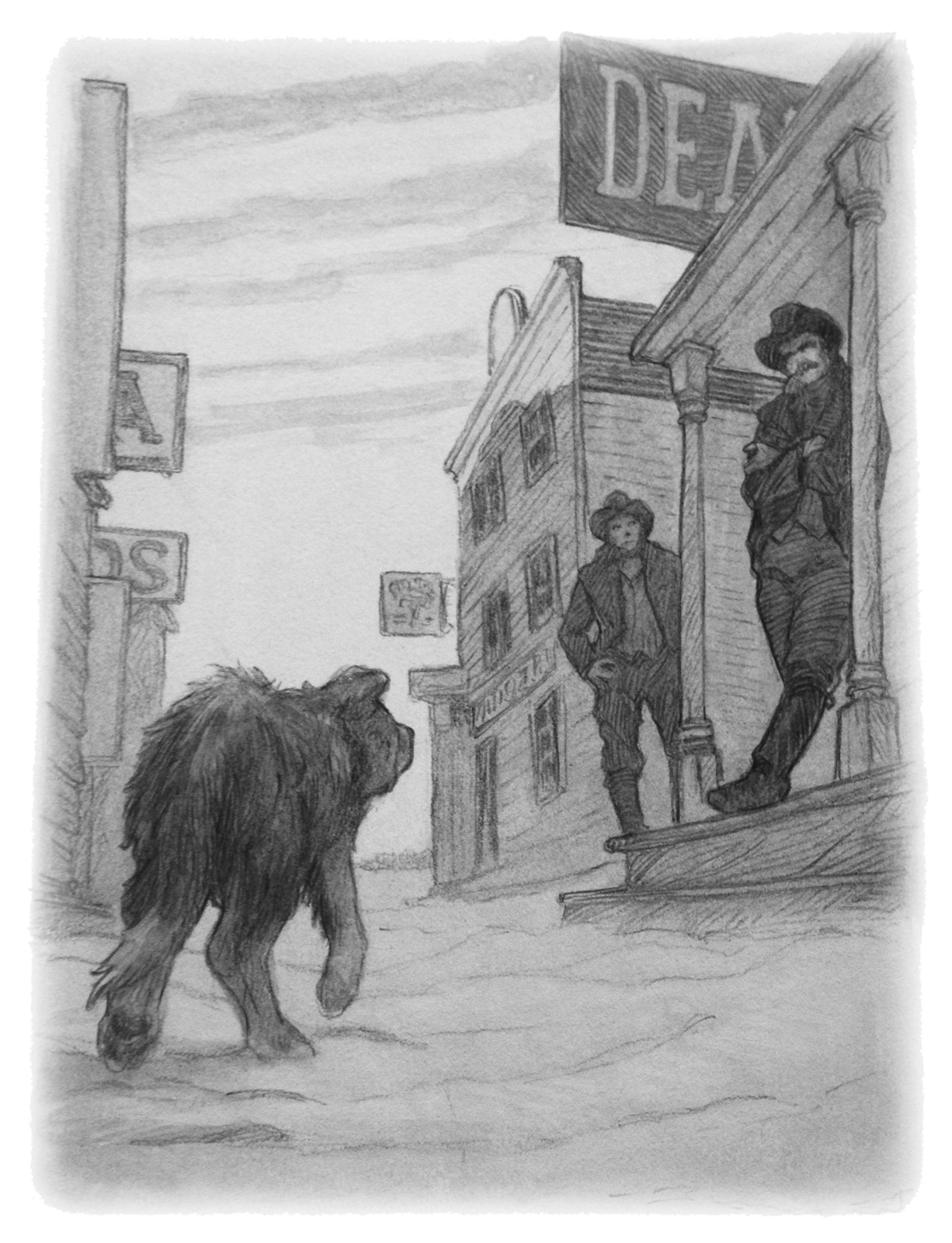

The sun peeked over the horizon as I trotted down the snow-packed street. A few flakes swirled from the graying sky, but the storm had ended. Wood buildings flanked each side of the narrow way, leaning in the wind. Shutters banged. Ahead of me, music and friendly sounds came from one of the lighted buildings.

A group of men stood on the stoop. I approached them with a wag of my tail.

“Get outta here, skinny cur!” One of the men threw a snowball at me.

“There should be a law that says any stray lurking on Front Street can be shot,” another said, flicking his cigarette at my feet.

“Law?” a third asked with a chuckle. “What’s that?”

I slunk into the shadows, where a pack of dogs tussled over food. My insides rumbled emptily. One of them growled at me and I flattened my ears and looked at the ground. When they saw I was not a threat, they kept eating. But I knew from their bristled hair that I wasn’t welcome.

I smelled salty water. Water meant fish. I trotted from the street to a stretch of frozen sand by the sea. As the sun rose higher, it glistened off piles of snow. I gazed toward the horizon, listening to the crash and boom of the ice breaking apart.

Row after row of tents extended to the edge of the water. Sleepy-eyed men were slowly emerging from some of them. My ears pricked. Were they friendly? Or would they treat me the way Carlick had?

Tired now, I walked among them, hoping for a whistle or an encouraging “Here, boy. Have a bite of breakfast.” But few glanced my way, and those who did had hard, uninviting eyes.

My stomach rumbled. Lowering my nose to the sand, I trotted along the edge of the water, hunting for washed-up fish. I smelled decay and rot, and found a pile of bones and slimy scales. Then the rich scent of boiling walrus reached me.

Under the wood pilings of a dock, an Inupiaq family camped. They wore fur hoods against the morning cold. One had a baby strapped to her front. She stirred an iron pot over a driftwood fire. All three watched me, only their dark eyes moving.

Then the largest one held out a sliver of meat. Food! I stepped toward him, but glanced up at his face. There was no smile, and I spotted a leather strap in his other hand.

I leaped away. He raced after me. I galloped along the shoreline and then darted between stacks of wood crates that reached to the sky. I hid in the dark crevice and waited.

When I peered out, the man was still there. Again, he held out the meat for me but the leather strap lay at his feet.

I retreated into my hiding place. There was no other way out of the tunnel under the boxes. I was trapped.

Exhausted, I lay my head on my front legs. Night would fall. I would wait.

My belly ached. Many days had passed since I had arrived in Nome with little food. Dark nights prowling for a meal and sunlit days hiding in the tunnel had left me weak.

I needed to eat.

I trotted through the sea of tents to the shoreline. Two men worked on the beach. Their attention was on the sand that they shoveled and sifted. If they had seen me, they would have chased me away. A dog as a pet would mean less food for them. Or they might try and catch me since the quick sale of a dog to a driver might bring in needed money. To a hungry native, a dog might also mean a meal in a stew pot.

A dying fish flopped in the sand. Licking my lips, I pounced on it.

A boot found my ribs before my claws found the fish. “Get, before I kick you clean to Seattle!” I skittered away.

More men rose from their tents to start their day. I hid behind a barrel and watched for a dropped morsel or untended pot.

Two men stirred the coals of a smoky fire.

“Gotta get to work,” one said to the other. “I heard a ship’s arriving soon. More men coming with high hopes of finding gold.”

The second man grunted. “That means more men with big dreams coming to steal our claim.”

I heard a sizzle and sniffed the air. Bacon. Once before I had risked a hot pan and burning coals for bacon—and I had almost gotten shot.

I dared not risk it again.

I sneaked away, darting between tents, wooden pilings, and crates, still looking for something to eat. My eyes widened. Someone had left an open can sitting on a rock. Sprinting forward, I grabbed it in my powerful jaws and raced to my hiding place.

Beans. I lapped them from the can, careful of the sharp edge, and from the ground where some of them had spilled. Not as good as bacon, but at least they filled my belly. Now I could fall asleep for a bit.

Daytime was dangerous. I would come out again when night fell. In Nome, that was a long time from now. The sun seemed to sit in the sky forever.

Closing my eyes, I dreamed of a home filled with kind words—and maybe even bacon.

Night. There was no moon, no stars, but Front Street was lighted by torches and lanterns. Music and laughter rang from buildings brimming with people. Men strode down the wooden walkways and staggered into the muddy streets. I stuck to the lighted byways, searching for food left in trash cans or bones tossed from a doorway.

A man lay sprawled on his back in an alley. Though he seemed to be no threat, I gave him a wide berth.

My nose picked up the scent of bread. A half-eaten loaf, soggy and dirty, poked from a snowdrift by the front steps of a building. Men lingered on the top of the steps, smoking. Did I dare?

My aching belly gave me no choice.

Rushing from the shadows, I snatched the bread and ran under the wooden steps. It was gone in two bites. Voices rose above me.

“Hey, Carlick, was that the beast of a dog you’ve been looking for?”

Carlick. Even after all this time, I knew that name.

“Might be. If you can catch him, I’ll pay a reward.”

“How much?”

“Ten dollars.”

“Sounds like easy money to me.”

I heard the clomp of boots and then a face peered at me. My heart beat faster.

“Hungry, boy?” The man sounded friendly. He held out a sausage link.

I drooled. I was so hungry.

“I’ve been trying to catch that blasted dog for three weeks,” Carlick said. “Name’s Murphy. There’s a brand on his shoulder. If you gents can snag him, I’ll throw in a round of whiskey.”

A flurry of boots thundered above and around me. “Hurry and get behind him on the other side of the steps!” A hand grabbed my tail.

Panicking, I barreled forward and leaped from under the steps, knocking one of them clean off his feet.

“Hey!”

I didn’t dare look over my shoulder, but I could tell by the pounding of feet that more than one person was after me.

“Get that dog! Fifteen-dollar reward!”

I ducked under a parked wagon and burst out the other side. More men leaped off the wooden walkway to my left and ran after me. I headed left, into a throng of people.

“Don’t let him get away!”

I was surrounded. The only way out was to knock someone over. I was about to jump when I heard the crack of a whip.

“Let me at him!” Carlick said.

I sank to my belly.

Pushing through the men, Carlick approached me. “Finally I’ve got you. Now I’m going to teach you not to run away from me ever again.” He raised the whip.

Whoo whoo! A ship’s whistle blasted far in the distance.

“It’s the Tacoma!” someone shouted. “Thank the Lord she’s finally here. Fresh supplies!”

In a wave, the men scurried toward the beach like rats. Carlick hollered after them to stop, but none turned around. Suddenly he was alone.

I lifted my lip in a snarl. Once I might have been able to take him. I used to be as big and strong as a man. But now I was thin and weak—and frightened of that whip. I had known the sting of it too many times. Tucking my tail, I fled into the dark.

“I’ll get you yet, you miserable cur!” Carlick shouted. “And then you’ll wish you were dead.”

I had escaped again. I knew next time I might not be so lucky.