CHAPTER NINE

A Sudden Change

August 5, 1900

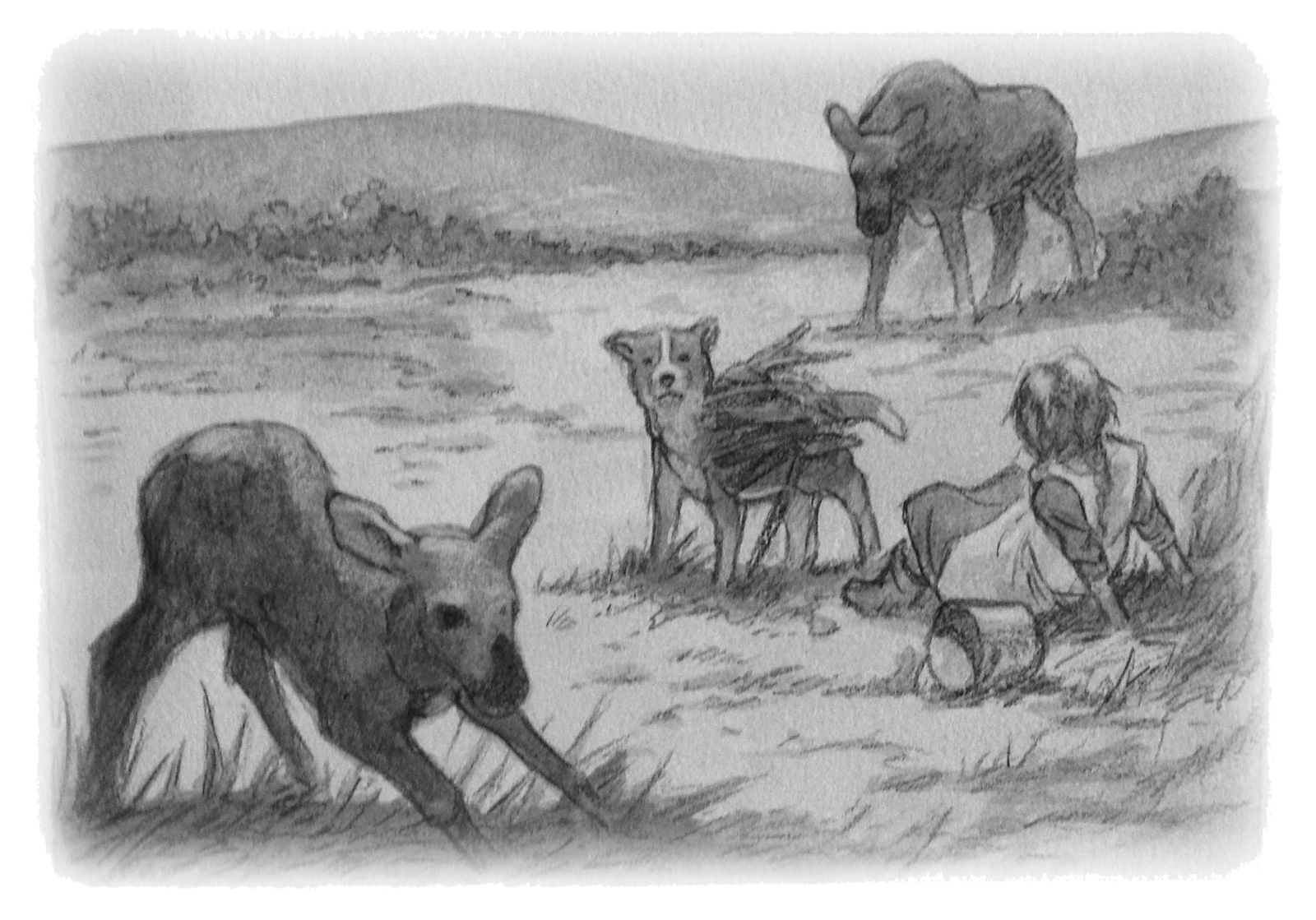

Grabbing Sally’s long skirt in my teeth, I yanked her out of the path between the moose and her calf. The cloth tore and she fell. Her bucket tipped over and blueberries scattered everywhere.

“Murphy!” She swatted me on the nose.

Sally had never hit me before, and the pain startled me. For an instant, I remembered my days with Carlick and was filled with sadness, but then the moose stepped closer to us.

She swung her head from side to side, glaring and my heart quickened. Just then the calf struggled to its knees, rump in the air, and rose on its gangly legs. I barked, trying to warn Sally.

Startled, she turned and saw the calf and its mother. Stifling a scream, she crawled from the bushes and up the hill as fast as she could.

I barked again. My hair bristled and I backed down the hill away from Sally in fear.

The moose leaped, her forelegs pawing the air. I darted away, the firewood banging my side, and ran past the calf. The moose galloped after me, crushing the brush in her anger.

From the corner of my eye, I saw Sally scramble to her feet. Grabbing the bucket and satchel, she ran up the hill and disappeared over the side.

I raced on, trying to get away from the mama moose, blundering through brambles and flowers. The wood on my harness caught on branches and ripped from the straps.

Finally I could no longer hear the moose. Panting and tired, I slowed. When I looked back, she stood over her calf, lovingly cleaning it with her tongue.

Relief filled me. Now I had to find Sally. I trotted up the hill, giving the moose and her baby a wide berth. Dropping my head, I caught her scent, which zigzagged through the brush.

“Murphy.” I heard a low call. She stood up from behind a hillock and waved urgently. I ran up to her and she gave me a hug. I wagged my tail and whole rump with joy. “I’m so glad you’re all right. Thank you for saving me. I didn’t see the moose or her calf until you barked.”

I licked her face, which was pale. Usually Sally was brave, so I was surprised to see her cheeks so white.

She took my head in her trembling hands. “I am so sorry I hit you. How could I have doubted you? It will never happen again. I promise. The boys in town were wrong, you aren’t a scaredy-cat.”

Only I was. I ran from the moose just as I had run from other dogs, the boys in town, and Carlick. But since it had chased me instead of Sally, she had been able to get away.

“What happened to your dress, young lady?” Mama asked when we finally returned. She stood in front of a smoky fire outside our tent, and I could smell beans and beef simmering.

“My dress?” Sally echoed. Her white pinafore was streaked with mud and her flowered skirt was ripped where I had grabbed it. Before coming home, she had again picked up more sticks and tied them to my harness. But we had lost all the blueberries.

“Where is your bonnet, what are those things on your feet, and where have you been?” Mama’s voice rose high and tight like the day she had given Sally a shake. I slunk to the other side of the fire, wanting to get away.

“I was fishing.” Sally pulled the oilcloth-wrapped fish from her satchel. “And collecting wood. The driftwood on the beach is about gone. You needn’t have worried. Murphy was with me.”

Mama didn’t even glance my way. For a long moment, she stared at Sally. When she did speak, her voice had dropped to almost a whisper. “Look at you, my lovely daughter. Your hair is tangled and your skin is as brown as a native’s. And instead of being a Gibson girl, I am a mess too. My one good dress has been ruined, and my fingers are sore from typing all day. Our house is filled with sand, and the sides flap and the roof leaks during storms. Grandmama was right. We never should have come to Nome.”

“Grandmama was not right,” Sally protested. “I love it here. Yes, it is wild and cold and we live in a tent. But the tundra is beautiful and you should have seen the blueberries. We would have brought you a bucketful, only the moose—”

Sally caught herself, but not before Mama heard her. Her face drained of color. Then slowly she turned away from her daughter, bent over the pot, and stirred. “Supper is ready,” she said tightly. “I am not hungry and have typing to do before I retire.” With sagging shoulders, she went into the tent.

Sally’s lower lip quivered as she watched her mother go. “It’s all right, Murphy.” She untied my harness straps. “It’s just that Mama works day and night. She’s more tired than angry. She’s right about the tent, though. We must find gold so we can buy a cabin. Come. Let’s fry these fish. A good meal will make her feel better.”

But a good meal didn’t tempt Mama. Rapid click-clacking came from the tent, and no amount of cajoling on Sally’s part would persuade her mother to stop typing and come eat. Much to my delight, I got to eat a whole fish, plus part of Sally’s, for now she wasn’t hungry either.

When the frying pan had cooled, I licked up the last of the lard. Then Sally washed it with water and sand. By the time we had finished, the sun was lowering for the night.

When we returned to the tent, Mama stood outside with a creased piece of paper in her hand. “I have written to your grandparents, Sally,” she said. “I have told them that we are booking passage on the Lucky Lady for home.”

For an instant Sally was too stunned to speak. “Y-y-you mean leave Nome?” she stammered. “But Mama, we can’t. I love it here.”

“Tomorrow I am buying tickets. The steamship leaves August 7; that’s in four days. We will arrive in Seattle by the end of August. We may miss your Grandfather’s arrival here in Nome, which is unfortunate, but I will leave word for him. Grandmama will be triumphant that we have given up, but I will deal with her.”

“Mama, no!” Sally cried out. “This is my home, not San Francisco.”

I whined anxiously, hearing the emotion in their voices. Things had been so right since I met Sally and Mama. Now suddenly they were so wrong. And I didn’t know how to help.

“It’s done, and I will hear no more of it,” Mama said. “Now pack a valise. We are going to the bathhouse to wash ourselves and our clothes. We may not be Gibson girls, but we needn’t smell like beggars.” She pointed the letter at me. “That goes for you too, Murphy,” she added before disappearing into the tent.

I lowered my head at Mama’s stern words. But when I glanced over at Sally, her eyes were narrowed and her lips were pressed firmly together.

As she stared after Mama, her fingers found my head. She stroked my ears just the way I liked and said in a low voice, “I believe our plans have changed, Murphy. We must stake our claim sooner than I thought. I am not leaving with Mama on the Lucky Lady. As soon as my gear is ready, we are off to the Snake River to find gold.”

I understood the word “gold,” but I did not know the rest of Sally’s words. Still I shivered, sensing that what had just happened between Mama and Sally would forever change all our lives.