CHAPTER TWELVE

Lost

August 20, 1900

The storm continued for four days, pummeling the tundra with wind, rain, and lightning. Sally and I dined on canned beans and sardines, and we only left the burrow to do our business. Even then, venturing just three feet up the bank, the fear of being swept away was real, and she held on to my collar as we made our way behind a bush. Each time we returned soaked, it took longer and longer to warm up.

Sometimes Sally shook with the cold. Her clothes, my fur, and the lone blanket stayed damp. The fire had long since died out. Fortunately the burrow didn’t collapse, though water leaked around the edges of the oilcloth and pooled by the entrance.

When there was enough light, Sally read to me from Grimm’s Fairy Tales. “Hansel and Gretel” was her favorite story. She delighted in switching voices for each character, cackling hysterically when she was the witch.

“I would never be as silly as Hansel and drop bread crumbs to find my way,” she scoffed. “You would gobble them up and so would the birds, and I would be as lost as Gretel.”

Later, when it grew dark, Sally would fall into a restless sleep. That’s when I grew alert. My ears stayed pricked for signs and sounds of danger. What if a bear found our buried food? The river might reach our hole. A wolverine could blunder into our burrow. Or a poisonous spider might crawl from behind the oilcloth.

Finally the storm blew itself out and the sun rose hot and bright. We emerged like foxes from a lair and shook ourselves. Sally shed her wet clothes. She washed them in the river and draped them over the willow to dry. Then she gathered wood to make a fire.

I bounded up the bank and raced around the tundra, glad to stretch my legs. A ptarmigan burst into the air, and I set my sights on hunting. A diet of beans had left my stomach wanting.

I didn’t like leaving Sally for long, but hunger drove me. Finally I brought back a hare. I held it high and proud as I trotted into camp. By then, Sally had a fire burning. The blanket and oilcloth, which she had also washed, hung on sticks to dry.

“Murphy, you are a wonder!” Taking the hare, she twisted a hind leg and began to pull off the hide. “I am glad Grandpapa taught me how to skin and cook a rabbit,” she said. “We need fresh meat in our bellies. Oh, I miss him! I imagine he and Grandmama will be glad when Mama arrives home safely. Not that San Francisco is home to me anymore. I wonder if I will even be missed.”

The roasting hare smelled delicious. Sally buried several potatoes in the coals and I knew we would have a feast.

While we waited for the food to cook, Sally waded into the water. “I’m going to find that nugget, Murphy. Or one like it,” she said, as she began to pan. “We missed four days due to the rain. August is coming to an end, and the storm was only a taste of winter. I know we must head back to Nome soon, but I won’t leave until I have my prize.”

Sally scooped sand and dirt from the river bottom into the pan. Then she dipped the pan into the water, swirling and shaking it, intently watching for gold. Finally I had to bark, reminding her that the hare was done.

She ate quickly, tossing me the bones, and then went back to work. In her zeal, she forgot to bury the rabbit hide away from our camp so it would not attract wild visitors. I dragged it far into the tundra and left it, stopping to eat some gooseberries on my way back.

A grunt made the hair on my back rise. I crouched and peered from behind the scraggly bushes. A bear and her two cubs were dining on berries too. Their silver-tipped hides were glossy. The mama bear’s claws were long and sharp as she stripped berries from the branches.

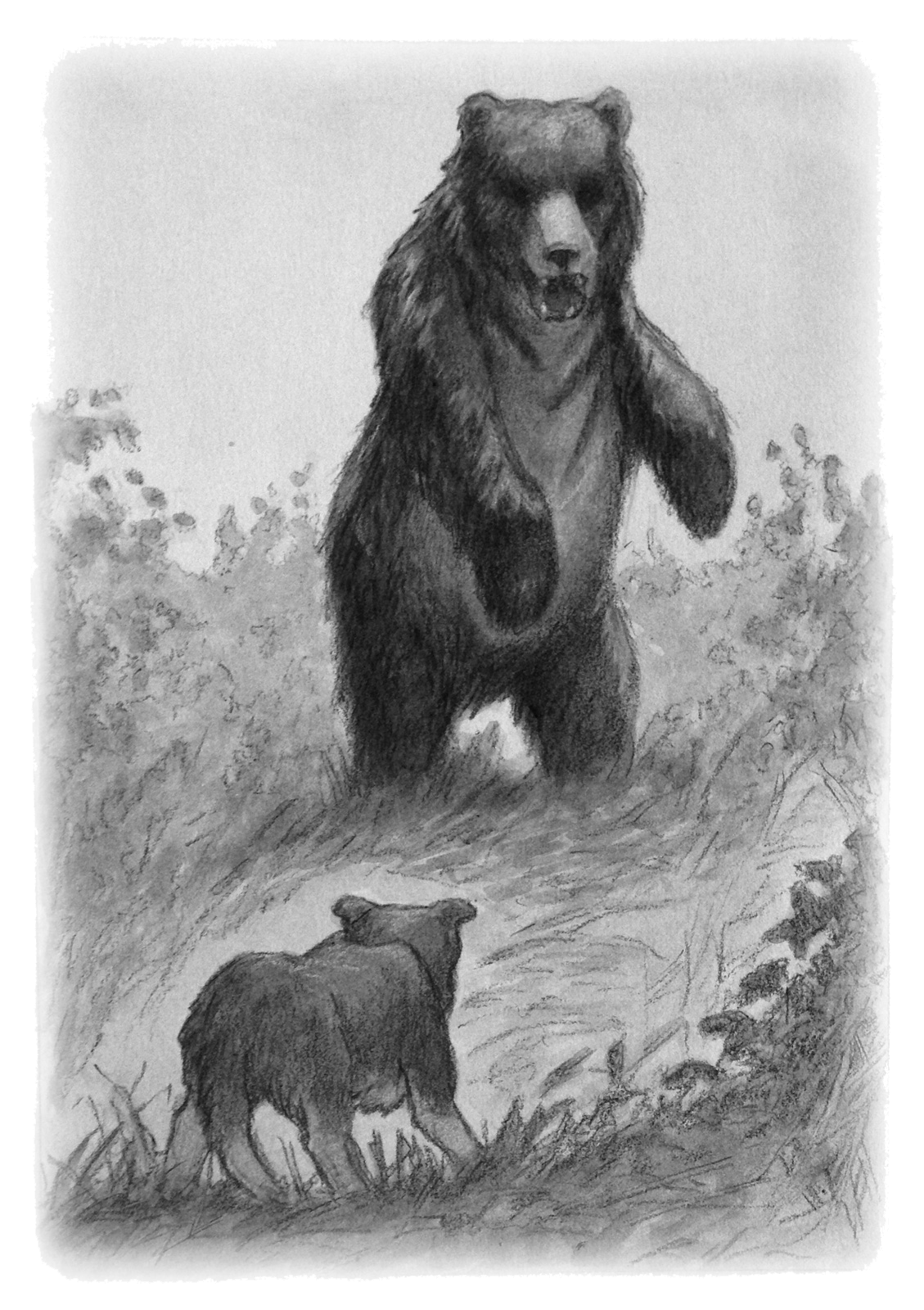

The cubs gamboled around their mother, who was as intent on berries as Sally was on gold. I did not dare run. But then the mother bear’s nose began to twitch and I knew she had smelled me. Nothing is fiercer than a mother grizzly guarding her cubs.

I flattened myself against the boggy earth, trying to disappear. She rose on her hind feet and looked around, huffing. I squeezed my eyes shut, wanting to disappear into the ground. Dropping to all fours, she began to lumber in the direction of the camp.

I couldn’t let her find Sally. Leaping up, I barked, startling her. The cubs squealed as if hurt. With a clack of her teeth, the huge bear sprang toward me.

Grizzlies are fast, but not as fast as a frightened dog. I raced away from Sally and our camp, zigzagging from hillock to hillock. My paws, stabbed by thorns and scraped by roots, were raw and bloody.

When the mother bear charged after me, the babies followed, bawling because they couldn’t keep up. When it seemed I could run no longer, the big grizzly stopped. Turning, she gathered her cubs and peacefully headed toward the horizon as if the encounter had never happened.

I dropped to my belly, panting wearily, until their silvery backs were out of sight. By then it was dark. I sat up and looked around. The tundra flowed around me like the sea. I had no sense where I was. Which way was the river?

Sight would not help me. I had to rely on my nose.

Dropping my head, I retraced my steps. The bears’ scents wound to and fro, and I often had to stop and circle back. I feared for Sally, who’d never been alone at night. Not that I was a great protector. It seemed all I could do was run away.

I quickened my step, stopping only to find my trail or listen for the river. Did I go in this direction before? With the bear hot on my tail, I had run blindly.

The chilly wind made me shiver. The vast sameness of the tundra confused me. I caught my scent again and trotted off, suddenly realizing I was tracking back the way I had just come. Sitting on my haunches, I tipped back my head and bayed.

“Murphy!” Sally’s voice was faint, but it was enough.

With renewed energy, I galloped toward the sound. A distant light glowed in the air.

“Murphy!”

I woofed, telling Sally I was coming. The light bobbed closer as if she was running too. With one last leap, I landed at her feet. She dropped her torch, which hissed in the bog.

“I thought you were gone forever!” She hugged me tightly against her. “What happened? Where were you?”

Lost, I wanted to tell Sally, but I could only wiggle and nuzzle her.

“It doesn’t matter. Only you must never leave me again. Nothing is more important than you—and Mama—I realize that now.” Sally choked on her words and I could hear the sob in her voice. “It doesn’t matter if we don’t find that nugget. Tomorrow we’ll head back to Nome. If Mama’s there, if she didn’t leave for Seattle, I’ll tell her how sorry I am—about leaving her and making her worry. Oh, I hope she will be there!”

Scrambling to her feet, Sally wrapped her fingers around my collar. Then she picked up the torch and held it in front of her. It shone on a piece of paper stuck on a thorn. “This way, Murphy. I marked my trail with pages from Grimm’s Fairy Tales so I wouldn’t get lost. I wasn’t going to be as foolish as Hansel. Now let’s go back and start packing. We’ll leave in the morning.”

I barked, ready to go home too. I’d had enough of wolves, mosquitoes, storms, bogs—and bears!