CLAUDE MCKAY

BORN: SEPTEMBER 15, 1889, CLARENDON PARISH, JAMAICA

DIED: MAY 22, 1948, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

WRITER, POET

AS SOMEONE WHO LIVES at the intersection of Black and queer, I’ve been told that my Blackness comes before my queerness. As if those two things can be separated when I enter a space. As if we must walk around as pieces of ourselves rather than whole people. As if our queerness will be a threat to our Blackness and the Black community as a whole. Claude McKay faced the same dilemma.

He was a Jamaican-born writer and poet. Although he was bisexual, he never really lived that truth in the public eye. At six years old, he went to live with his older brother, Uriah, who was a teacher. Uriah helped Claude learn to love reading and writing. Claude was also mentored by the philosopher Walter Jekyll, who would eventually help Claude compose his first book of poetry in 1912, Songs of Jamaica. Claude left Jamaica for the United States that same year.

A few years after arriving in America, Claude read W. E. B. Du Bois’s book The Souls of Black Folk, which greatly affected him. He also married his childhood sweetheart. The relationship ended quickly, and Claude left his wife and daughter.

He became involved in Black politics. Claude felt that the focus on respectability and elitism shown by the leaders of the NAACP and the Black nationalism movement weren’t in the best interests of a Black revolution. At the end of the decade, he traveled to the United Kingdom, where he became involved in socialism, and then on to Russia and France.

Despite being abroad for some time, Claude still became a force within the Harlem Renaissance. His poetry took a radical view of race. He made it clear in his work that he hated racism. He also displayed his love of Jamaica throughout his writing. In his sonnet “If We Must Die,” he challenges Black folks to have courage to fight against those who oppress them. I encourage you to read the full poem, but these lines say it all:

Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

Claude McKay was a truth-teller. He was fearless in his depictions of the totality of Harlem. As a kid, I thought of the Harlem Renaissance only as a glamourous time. The movie Harlem Nights, which starred Eddie Murphy and Della Reese, always made the Harlem Renaissance seem so fabulous to me. The characters were dressed in elegant suits and gorgeous dresses. The scene was about opulence. Even Michael Jackson’s “Smooth Criminal” video made the Harlem Renaissance seem cool and stylish.

If we did study the Harlem Renaissance in school, it was only from this place of opulence and creativity. Harlem was the “birthplace of jazz music” and everything cool about Black culture. We never really learned about the lives of real people during that time. Black history is often taught in silos like this, where parts of the truth are left out of the narrative. Claude McKay filled in those parts of the story, even to the frustration of the most prominent figures during that time.

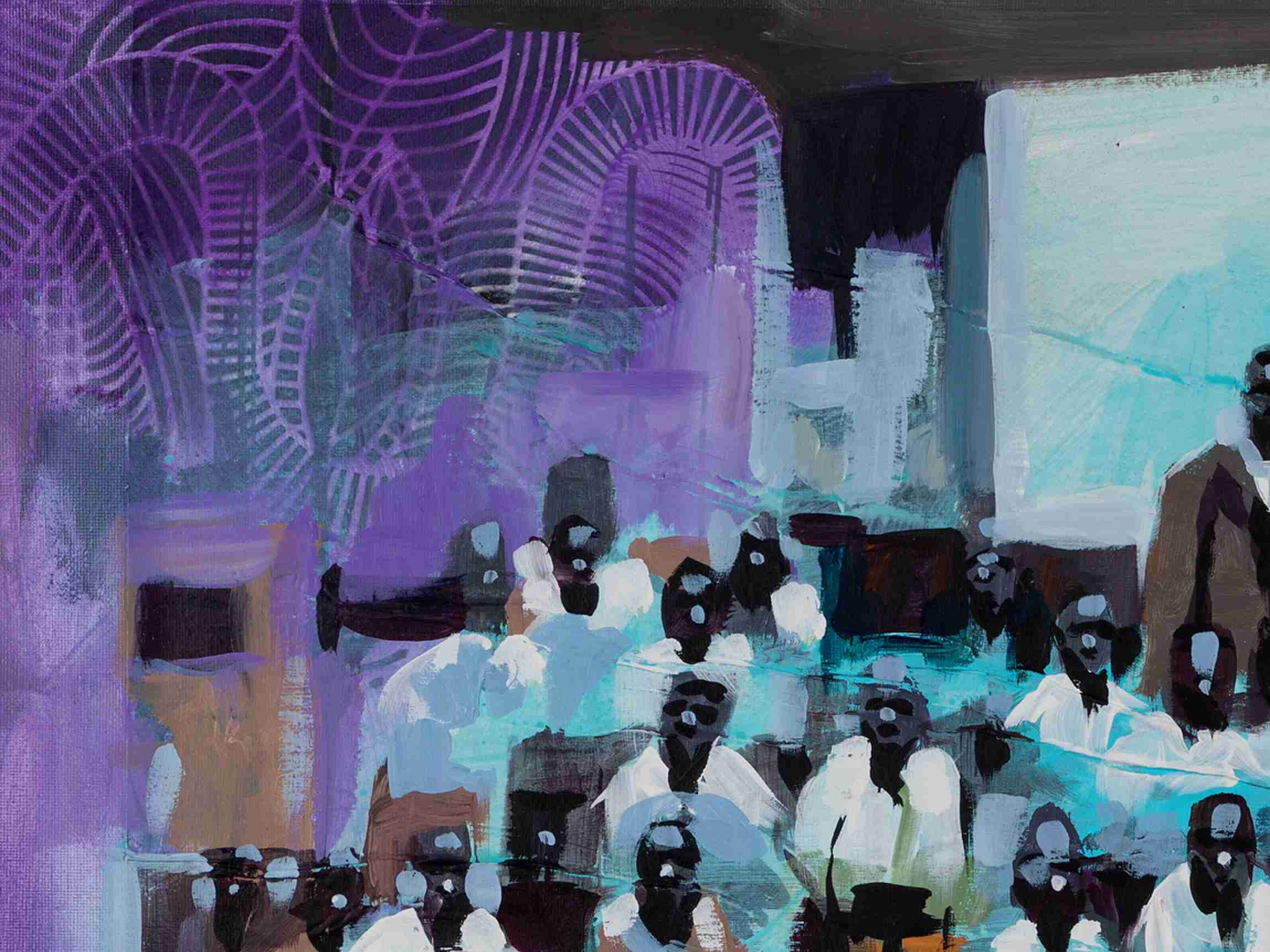

Claude’s most well-known work, the novel Home to Harlem, was a huge success both here and in the Caribbean. In it, Claude painted a colorful picture of the Harlem Renaissance. He did a deep dive into the sex scene, the lower-income classes, and the less-than-fantastic parts. He talked about the nightlife of Harlem in full detail: petty crimes, lawlessness, prostitution. His stories showcased how many people during that period merely survived instead of thrived. It wasn’t all glitz and glamour. Claude made sure the world knew that.

W. E. B. Du Bois wasn’t pleased. He felt that Claude’s “negative” depictions of Black folks were written for the white audiences who created the negative stereotypes Claude was critiquing to begin with. W.E.B. felt that artists should be showing only the affluent parts of our community, as a model for others to live by. However, Claude felt that W.E.B.’s approach was more like propaganda than art.

This reminds me of Black leaders like Al Sharpton and others who want to “bury the N-word.” Meaning they want Black people to stop using it. They believe that because that word was, is, and may always be used as a slur toward us—and one of the most hateful words our ancestors heard—that our use of it is also negative. But for those of us who do use the shortened form (n*gga), it is a term of endearment.

That word has been used in my household from my earliest memories. When my uncle says, “You know you my n*gga,” it is his way of saying, “I love you, support you, and will protect you.” We all repurpose language for our own benefit. The N-word is the same way. But trust I get it. Especially the generation that lived through the civil rights era and heard the N-word used against them. But there were also folks in my family who lived during that time who still used the repurposed meaning of the word. And I think that’s okay. It’s okay to have some people who don’t want to use it and some who do. We can have all parts of our community’s story be told.

It’s great that people want to talk about our achievements. Many did believe in W. E. B. Du Bois’s “talented tenth” model. However, this model shouldn’t mean that we don’t get to discuss the other 90 percent, or not see their lives as central to our journey.

There are some horror stories about how queer people are treated in Jamaica. And I want to be clear that most places on this earth are homophobic, but Jamaica is one of the most notorious. I’ve been to Jamaica several times, and each time loved it more and more. But I have also been warned that the things I do in America may not fly in Jamaica. I need to be very careful when I travel there. My experience in Jamaica helped me understand Claude McKay so much more. He had a great love for his home country even if he couldn’t fully be himself there.

When I wrote my young-adult memoir, All Boys Aren’t Blue, I had no idea that it would expand the story of the Black queer American past my own country. But now it’s been translated into French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Korean, with other languages to come. Claude McKay’s work also has a universal appeal that transcends race, gender, sexuality, and nationality—he broke barriers that allowed me the space to tell my story.

Claude continued to write poetry for many years—almost as a diary for his experiences moving through the world as a Black man. He has become known as a prominent liberal thinker of the Harlem Renaissance. It takes a lot of courage to live a life like Claude’s. Unafraid to go against whiteness as well as elites in his own community who wanted to hide parts of our existence.

Claude showed us writers how to tell the truth. And to be unafraid in that storytelling. As we live in an age where books about Blackness and queerness are being banned left and right, I think about how Claude McKay continued to write more stories even when being criticized. I take that with me.

If I must die, it won’t be in silence.