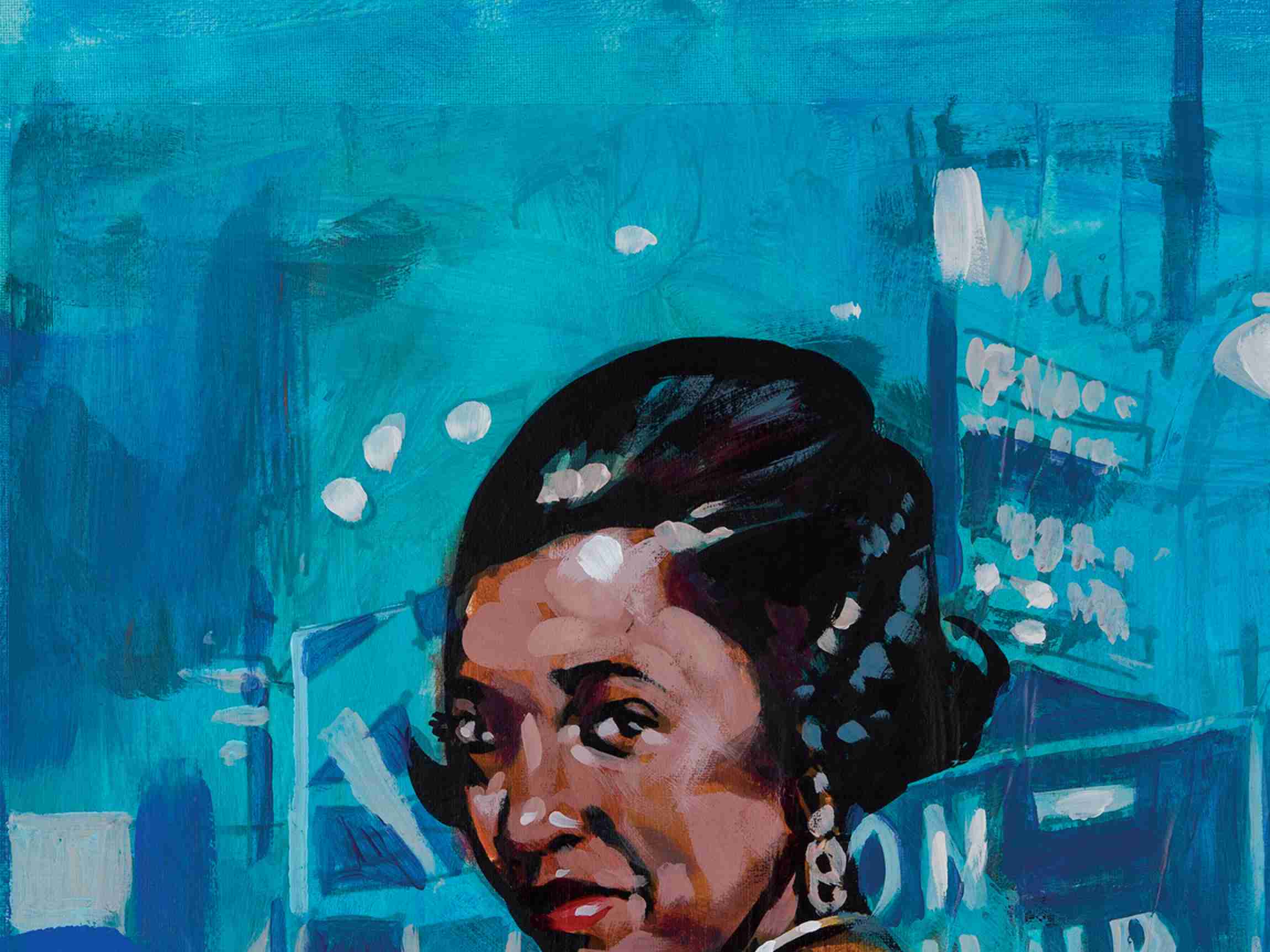

ETHEL WATERS

BORN: OCTOBER 31, 1896, CHESTER, PENNSYLVANIA

DIED: SEPTEMBER 1, 1977, CHATSWORTH, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA

SINGER, ACTRESS

Symbolism is a threat to actual change—it’s a chance for those in power to say, “Look how far you have come” rather than admitting, “Look how long we’ve stopped you from getting here.”

—George M. Johnson, All Boys Aren’t Blue

THE FIRST AFRICAN AMERICAN TO BE … Black people are still becoming “firsts.” It’s the lens through which a lot of Black history is taught in school. We are taught to be only as great as our achievements, which often leaves out most of our story. Every time I would see a “first” as a child, I’d get excited. I had a glass-half-full mentality. I used to think, “Look how far we have come.” Now I say, “Look how long they kept us from achieving what we have always deserved.” That was the first thought that came to my mind when learning about Ethel Waters.

I used to think of Ethel Waters only as a singer. Of course, she was one of the greatest singers of the Harlem Renaissance, one of the best vocalists of all time. She performed hits like “Dinah” and the iconic “Stormy Weather”—although the rendition we hear the most now was from Lena Horne and Etta James. That’s all I knew of Ethel before researching this book.

But Ethel Waters was and is one of the most important figures for us. She broke down barriers and kicked in the doors unapologetically, despite her life starting from a place of trauma. Her mother was raped as a teen and gave birth to Ethel in 1896.

In the Black community, we talk a lot about how violence is a cyclical thing. That violence enacted upon the parent can influence the raising of their child. Although she played no role in her creation, Ethel described the hatred she received from her family as a living reminder of her mother’s trauma. I can’t even begin to imagine what Ethel faced.

However, Ethel surpassed the odds. On her seventeenth birthday she went to a costume party at the Philadelphia club Jack’s Rathskeller, where she ended up singing a couple of songs. Ethel wowed the crowd. So much so that she was given a job at the Lincoln Theater in Baltimore. But she made only ten dollars a week from her performances, because her business managers robbed her of her tips.

From there she went on to vaudeville, like other Black singers of that time. She eventually joined the carnival circuit and toured the country before landing in Atlanta, where she would find herself working alongside Bessie Smith around 1916. Bessie, who was a force in her own right, complained that Ethel was singing blues songs, too. Despite this, Ethel would continue performing there before moving on to Harlem in 1919.

She recorded with Black Swan Records, becoming the highest-paid Black recording artist for a few years. In 1924, Paramount—yes that same Paramount you all know nowadays—bought out Black Swan. Ethel eventually left that deal and started recording for Columbia Records—yes, that same Columbia Records.

In 1925, she began performing at the Plantation Club in Harlem, followed by a stint on Broadway. She continued to bounce between theaters and nightclubs, and eventually began acting.

Very early in her career, Ethel did identify as bisexual, but never in a public space. This is important when we think about the trajectory of her life and her successes. Publicly, Ethel was married three times to heterosexual men, but she was also known to date women. This makes me think back to Countee Cullen’s story. There was pressure for one’s image to look a certain way. And to be clear, being bisexual means just that. You can be married to someone of the opposite sex who is heterosexual, and your identity can still be bisexual. However, some bisexual people choose never to show their full truth to the public for fear of retaliation. When you read a biography of Ethel, her bisexuality may be left out of all the things she accomplished.

At the core of Ethel’s story is her list of “firsts.” First Black woman to integrate Broadway’s theater district. First Black American to star in her own television show. And the first Black woman to be nominated for a Primetime Emmy. Accomplishing any one of those things would be a hell of a career, let alone all three. But what did being the first really mean for Ethel Waters?

Breaking barriers in all those spaces didn’t come without conflict or struggle. She was still Black and a woman, two identifiers that have always come with their own distinct oppression—even more so when you live at the intersection of the two. Success doesn’t negate the pressures that come with it. You’re sitting alone at the top of a mountain that no one ever gave you the equipment to climb.

In Ethel’s list of accomplishments, the most interesting one for me is this: second Black woman to be nominated for an Academy Award. The nomination was for her role in the film Pinky.

Many of us in Black communities know about Hattie McDaniel being the first Black woman to be nominated for an Academy Award. But do we know the second person to do it? Therein lies the problem with symbolism. What happens after history is made? Do things change? Or is that symbolic moment simply used as the token, an excuse? The first gets remembered, but what about the tenth? When do we get to a point where there are so many Black people achieving historic success that the order in which they do it isn’t even a thing anymore? That’s my goal. To find my success and help others do the same.

I’m sure that I am a first of something or will be a first one day. But it doesn’t matter to me if I ain’t making sure that number eventually has some zeroes after it. Unfortunately, that’s not everyone’s mentality. I think gatekeeping occurs because we have seen so many “seconds” be forgotten. People who make it to the top will give you a rope to climb rather than stairs or the elevator. You know, the whole “I struggled, so you need to struggle, too” refrain.

Ethel once said:

The white audiences thought I was white, my features being what they are, and at every performance I’d have to take off my gloves to prove I was a spade.

This quote raises a question: Were a lot of Ethel’s “firsts” because people thought she was white? Was she a palatable Black woman to the white folks who dominated the decision-making process in show business? Even if it was, I love that Ethel never denied her Blackness and took it a step further to make sure those in the room knew it, too. She refused to be the token or the symbol of “change.”

It speaks to the importance of showing up in rooms and being who you are. I’ve discussed the notion of showing up as pieces of our identity for safety reasons and convenience—both valid. However, there is power in showing up as your full self, in disallowing the powers that be to strip you of parts of your identity. Like the spade on a playing card, Ethel was a Black symbol surrounded by whiteness. She refused to let that spade be anything else.