ZORA NEALE HURSTON

BORN: JANUARY 7, 1891, NOTASULGA, ALABAMA

DIED: JANUARY 28, 1960, FORT PIERCE, FLORIDA

AUTHOR, ANTHROPOLOGIST

I WAS RECENTLY ASKED, “If someone were to write about you after you passed away, what would you want them to say?” My response is pretty simple: “I want them to tell the truth. The good, the bad. The in-between. I don’t want to be on a pedestal. I don’t want anyone fighting over the decisions I made in my life, debating if I deserve to be grieved.” At the end of her life, Cicely Tyson said, “I did my best.” I’m doing my best. And I’m closing this book with someone who, despite all she contributed to this world, had to wait decades for folks to say the things that she deserved to hear before she passed away.

Zora Neale Hurston died poor and was buried in an unmarked grave. I’m going to start there because out of everyone in this book, she is likely the most important, most influential, and most talented person of the Harlem Renaissance—and just maybe of the Black lexicon of thought. It’s painful to learn time and time again how many of our greats died in poverty. I’m glad that who she is to us in her afterlife is much better than we treated her while she was alive.

I was a teenager when I first learned who Zora was. I remember it clear as day. Oprah Winfrey was presenting the TV original film Their Eyes Were Watching God, starring Halle Berry and based on Zora’s book of the same name. The night it premiered, I sat in the living room watching it with my mother, as we often did when TV movies came out. The film received a lot of pushback because it didn’t touch on the rawest parts of Zora’s novel. But that’s a common theme in Zora’s legacy. Her hard truths were simply too much for people.

Zora said in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, “I wrote Their Eyes Were Watching God in Haiti. It was dammed up in me … I wish that I could write it again. In fact, I regret all of my books. It is one of the tragedies of life that one cannot have all the wisdom one is ever to possess in the beginning.” She then went on to say, “If writers were too wise, perhaps no books would be written at all.”

I know years from now I will come back to this book and think, “I should have said this” or “I shouldn’t have said that.” However, that’s the beauty in writing. What I don’t say now can be said in a new work years from now. What I get wrong here, I can get right elsewhere. But there is nothing to get right or wrong if I never sit down and take the time to dig deep into the pit of my soul to tell a story.

Although Their Eyes Were Watching God is Zora’s most remembered work, her personal story is so much more.

Zora Neale Hurston was technically born in Notasulga, Alabama, but she never claimed it as her home. When asked throughout her life where she was from, she would say she was from Eatonville, Florida, the place she moved to as a young child. Zora truly embodied her Southern roots. From speaking with a drawl to the way her words and grammar were tied together, she saw the importance of language. And she understood that Black languages and accents were never monolithic—what many now call African American Vernacular English (AAVE) used to be seen as an unacceptable way to speak. Zora did not judge language as “proper” versus “improper,” as some Black intellectuals of her time did.

People often tell me that I tend to write and text exactly how I talk. Meaning they always read things in my sassy, kinda-Southern-twang voice. They say Zora was like that, too.

Zora was thirteen when her mother passed away. Her father quickly remarried, and sent her off to boarding school. However, her father later stopped paying tuition, so she had to drop out. Zora had a real passion for education and refused to let setbacks hold her up. She worked odd jobs before finding herself in Baltimore, Maryland, where she began attending Morgan College, which we now know as the HBCU Morgan State University. In order to qualify for free tuition, Zora lied about her age, saying she was born in 1901 rather than 1891, making her sixteen years old when she was really twenty-six.

Thankfully, she was never caught. After graduating from high school, she went to Howard University in Washington, D.C., to earn an associate’s degree. In 1925, she attended Barnard College and became the first Black American woman to graduate from the school. She was thirty-seven when she finally completed her education with a BA in anthropology in 1928.

Hurston was paid by Charlotte Osgood Mason, an American philanthropist, to travel the American South and record Black traditions, including folklore, literature, and hoodoo—a practice encompassing spiritual elements from various religions and indigenous ways of knowing, originally created by enslaved Africans in the United States. Essentially, Zora’s work has become an important time capsule of Black histories that otherwise may have never been so thoroughly studied.

During the late 1920s and early ’30s, she lived in Harlem, where she befriended Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Alain Locke, and Wallace Thurman. Together they considered themselves the “Niggerati.” They started a magazine called FIRE!! Although it only had one issue, it caused quite the controversy: It contained stories and images of homosexuality and even prostitution.

I think this is a great time to discuss the discord around Zora. Some speculate that she was bisexual. There is a reason I opened this book with Langston Hughes, a figure whose sexuality some still question, and close with Zora.

Zora was married three times in her life, each time to a man. Two of these relationships lasted for a few years, and the other only ten months. I couldn’t find much information about her being in a lesbian relationship. However, one could view her writings about lesbianism, specifically in Their Eyes Were Watching God, as a window into who she was. Many of the Harlem Renaissance writers who never publicly identified as queer wrote about queerness, almost as if they lived vicariously through their works.

Zora once wrote:

If you are silent in your pain,

they will kill you and say you enjoyed it.

I’ve seen this quote hundreds of times. It has become one of the most well-known quotes in the Black community, a rallying cry for many of us afraid to speak up and speak out against the atrocities we face. There is a real fear of death when one fights against the oppressor. However, not speaking out about injustice has never thwarted death, but only delayed it.

As great as the Harlem Renaissance was, there was also a good deal of silencing. Interestingly enough, I’ve always thought of that quote from Zora and linked it to white supremacy. But in thinking of it now, I see that it also talks about the silencing we experience from our own. Even in spaces created by us, for us, many of us are not allowed to have a voice or be our full selves.

Zora and several other writers refused to be silent about the Black communities they represented—even if not fully discussing their queer identities in the public sphere.

Zora wasn’t afraid to speak her mind, which is partly why she had such a hard life in the end. She even foretold her own fate in a letter to W. E. B. Du Bois, where she asked him to gather resources to ensure that notable Blacks would not be buried in unmarked graves and fade away from history. This was not done, and as this book has showcased, Bessie Smith and Zora Neale Hurston were both buried in unmarked graves.

Although celebrated as one of the greatest figures of the Harlem Renaissance early on, she lived the last decade of her life in decline—both in the public eye and in her own community. So when she died, there was no one there to herald her or ensure that her work would be preserved.

Zora Neale Hurston passed away in 1960, broke and alone in a county-run nursing home. Workers at the nursing home were directed to burn all of her manuscripts and belongings since she had neither kin nearby nor any children. A Black police officer named Patrick DuVal knew Hurston, and he knew about the plans to burn all her items. He got to the nursing home just as a barrel filled with her things began to smoke. He put out the fire and essentially saved one of the most important writing collections of our time. But Zora herself had effectively been forgotten.

That was until nearly fifteen years after her death, when Alice Walker—the author of the iconic novel The Color Purple—wrote an essay for Ms. magazine titled “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston.” This essay prompted a resurgence in interest for all of her works. Publishers even began reprinting her stories.

Another quote from Zora:

All my skinfolk ain’t kinfolk.

I think this quote sums up so many of the different -isms, -phobias, and -ogynys in this book. As much as we want to believe that Black folks are here for other Black folks, our communities still have so much healing and learning to do—including the unlearning of colonialism.

Looking at the Harlem Renaissance, looking at how Zora was treated throughout her life, looking at how all of these figures had such obstacles to overcome from white folks and Black folks alike, it is easy to understand how Zora concluded that the people in her community would allow her legacy to be erased. That ain’t family. That ain’t kin.

I’ve seen so many say, “I was called the F-word before I was ever called the N-word.” Although this may be true for them, it is too generalized. If you only live in Black communities, as I did growing up, it would be less likely for you to ever hear the N-word—used as a slur, not the way we use it as a term of endearment. However, because I existed around mainly Black people, the othering of my existence was wrapped up in my queerness—which is why the F-word was my first slur.

As glamourous as the Harlem Renaissance seemed, as culturally shifting as it was, it didn’t stop the problems that continue to plague our community: Black folks opting to pass for white rather than existing in their own community—for reasons ranging from convenience to privilege to safety. Heterosexual Black folks being unaccepting of Black queer people. Black men criticizing and shaming the work and performance of Black women. Hierarchies based on class, gender, and identity—assimilating to the same oppressions we see throughout the white community.

Zora shouldn’t have had to wait till the afterlife to feel the love that she now receives from her skinfolk. This book is a small contribution in the reclamation of these important figures, who deserve their legacy to be told in its totality. Figures who deserve the love of kinfolk and skinfolk. A love without conditions. A love that never requires them to show up as pieces of themselves in order to be acknowledged.

Zora may have been buried in an unmarked grave, but today we know her name and what she meant. Alice Walker gave Zora a headstone that states, “Zora Neale Hurston. A Genius of the South.”

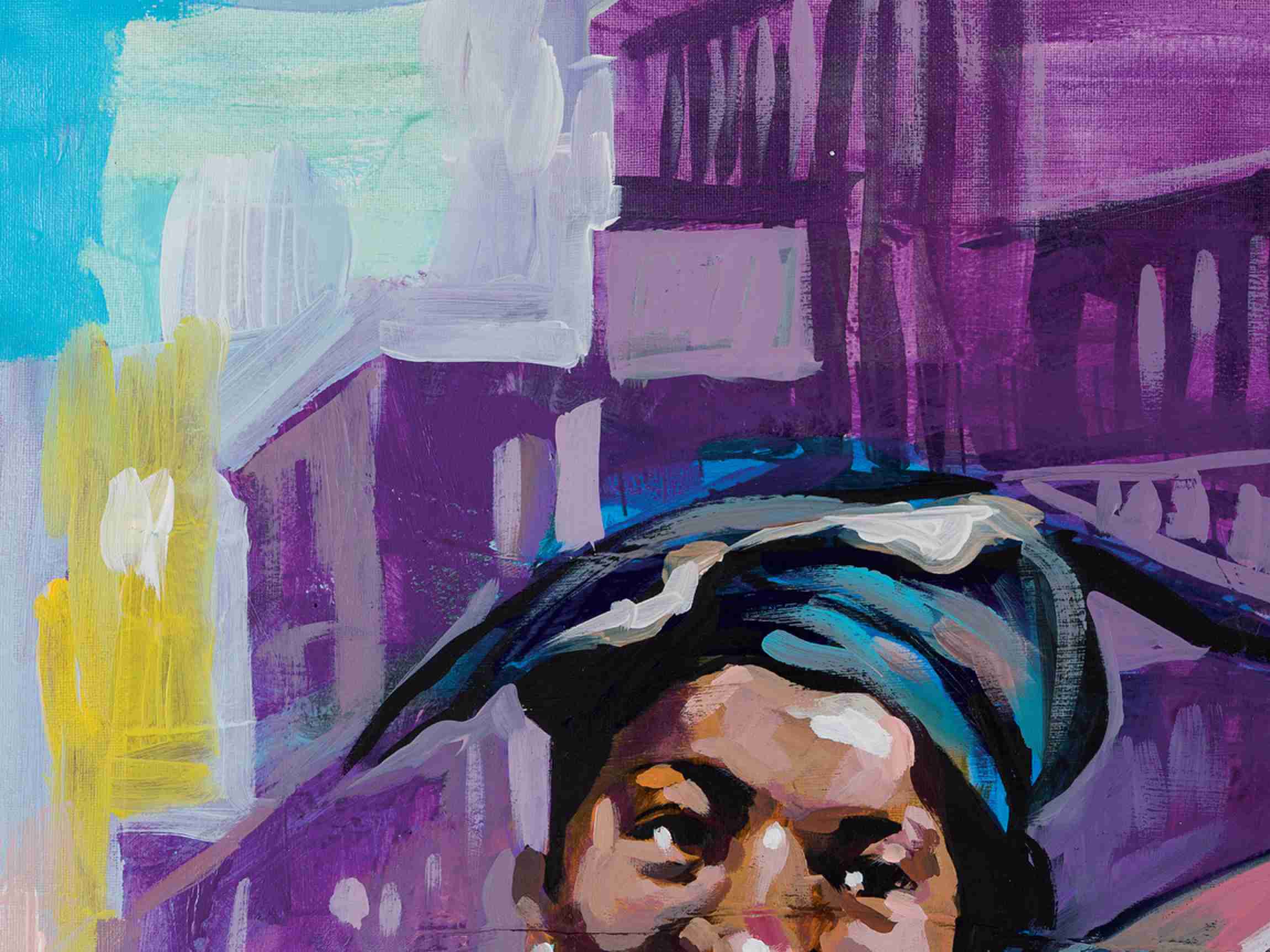

And that’s how many of us remember her, as a genius. That’s how we should honestly remember all the figures in this book. Some of the greatest geniuses we may have ever known. I call them “the Flamboyants.” Their lives were full of color, wisdom, and experiences that shined brightly beyond the confines of their time.