The basic processes of digestion we learned about in biology classes did not seem very exciting, but if you think about it in an imaginative way it is an awe-inspiring process. Our digestive organs recognise what we eat and secrete the right enzymes to digest all the different components of the meal. This enables us to eat a large variety of foods and use them to give us energy and to grow our bodies.

Digestion and assimilation

The taste and aroma of food stimulate our metabolic organs to secrete enzymes to help digest it. Carbohydrates, fats and oils, protein and minerals all go through different digestion processes as they are broken down. Our bodies accomplish a great number of energy transformations in digestion, keeping us alive, healthy and active.

Digestion breaks down food into its chemical components so it can be built up again into our own bodies. Not only the chemicals, but also the organisational energies that we take in have to be destroyed and in that process, stimulate our own organisational energies which use the nutrients. Our bodies are not machines but dynamic, living and self-organising. They need more than so many calories and so many grams of various chemicals. We need the stimulation of rhythmical organisational energies in our food to maintain the rhythms and harmony of our organs, our circulating blood, our breathing, our energy cycles, our immune systems, our thinking and feeling. Eugen Kolisko (1978, p.9) pointed out that all substances have to be transformed into substances which can exist in human blood. He gave a detailed description of the digestive processes.

The energy pattern and rhythm in each piece of food we eat is foreign to our own body and cannot be assimilated and used in that form. Food has to be completely broken down by our digestive enzymes then assimilated and built up again into our own energy rhythms and our own unique proteins. When protein is digested it is broken down into its constituent parts, then the body uses the formative energy released to builds up its own protein. A protein molecule is a highly organised structure of amino acids which themselves are complex organised molecules. The blueprint or energy pattern of each amino acid is needed to enable us to rebuild them after completely breaking them down by digestion. Steiner said that our bodies do not retain those blueprints, they need to be provided each day for us to be able to build our own protein (Steiner 1991, p.112). Each human makes their own unique protein – that is why DNA sampling can be used for identification at a crime scene. We particularly need the blueprint structure of each of these substances, particularly complex proteins,

Our bodies can only build healthy protein if we eat balanced protein foods containing all the essential amino acids. Plant protein is particularly important. The smaller quantity of protein in plant foods compared to in animal foods provides more stimulation of our own energies because plant proteins are harder to digest. Animal protein is more similar to our own protein than is plant protein.

Everyone has a unique digestive system, digesting these various types of substance differently. Some people are better able to digest food than others, depending on such factors as the health of their digestive organs and their psychological state. Wolcott and Fahey (2000) described many types of imbalance such as the rate of food oxidation, electrolyte/fluid balance and dominance of an endocrine gland, all of which can affect digestion and which vary between each person. Good feeding and care of babies and young children helps to build healthy digestive organs which can contribute to health in later life.

The rate at which we metabolise glucose has considerable affects not only on cellular functions and physical energy but also on our state of mind. George Watson (1972) categorised people into slow and fast glucose oxidisers, finding relationships between this metabolism rate and mental disorders. He found that fast oxidisers needed a different diet to improve their condition than that which benefited slow oxidisers. He also found that lack of particular vitamins could affect people psychologically, and also could affect their sense of smell.

The interconnections between our minds and our digestions is a further reason why each person digests the same food differently. Dr Edward Bach found a relationship between the predominant species of bacteria in a person’s gut and their basic attitude to life (Howard, 1990, p.7). Someone who is fearful has different gut bacteria to someone who is more relaxed and is enjoying life.

Our gut bacteria play a major role in digestion and assimilation. Scientists at the Institute of Food Research, UK, estimate there are about ten trillion microbial cells living in the human gut (Juge et al. n.d.).

Eating food in a fresh, natural state such as raw milk and yogurt and fresh salads assists with keeping healthy gut bacteria which protect against harmful bacteria.

With so many different factors affecting our digestion and assimilation of food it is no wonder that particular diets have different effects on different people. Chronic disease states such as leaky gut syndrome further complicate food assimilation. An unsuitable diet is unhelpful no matter how good quality the food is. This is why we all need to take responsibility for our own nutrition and health. Learning to be aware of the taste, smell and appearance of different foods and how they affect your energy levels and state of mind helps to build consciousness, both directly and through selecting the right, high quality food.

Relationships between plant and human energies

When you eat your five servings of fruit and vegetables a day, do you think about what types of fruit and vegetables? Generally we take into account whether they are starchy or contain more protein, trace elements, other nutrients and antioxidants. Also important is the question of what kind of fruit, vegetable or animal food. When formative forces are considered it could make a difference whether I eat an apple or a pear or a carrot as they each have different combinations of formative energies and rhythms. A leafy vegetable such as lettuce contains different energies from a root vegetable such as carrots. A broccoli head is actually a plant flower, so this contains different energies again.

When you eat an apple you eat the energy processes that were used by the apple and the tree it grew on to maintain life. When the apple that has been broken down by digestion is assimilated by your body, these energies stimulate your own energy processes. In earlier times people considered the whole plant or animal food rather than its constituents. The idea that a plant form can resemble part of a human body, indicating that it can be used to heal that part is generally dismissed as unscientific. It was a very ancient belief revived in the sixteenth century by Paracelsus as the ‘doctrine of signatures’ and also used in Chinese traditional medicine. There are some remarkable similarities often quoted such as that walnuts look like a brain and are good for brain function, and the lungwort plant is helpful in healing lungs.

Effects of eating different types of plant energy

Paracelsus and other alchemists identified three main types of energy, which they called ‘Salt’, ‘Mercury’ and ‘Sulphur’. Salt energies produce mineral salt forms. These energies are predominant in plant roots. Sulphur energies enable warm, metabolic, differentiating processes in plants, resulting in flowers and seeds. The mercurial energy refers to the flowing and rhythmic nature of all liquids, which flow between the salt and sulphur extremes. Mercury energies predominate in plant leaves.

Rudolf Steiner related different parts of the plant and their processes to different parts of the human body (Steiner 1991, pp.98, 106). He said that these relationships are the basis of how different parts of the plant have different nutritional effects in the body. Eating particular parts of the plant stimulates and nourishes corresponding parts of our body. Steiner visualised the plant as an upside down human. The roots correspond to our heads – the mineral energies in the soil which are taken up by roots are similar to the energies in our heads and nervous system. The leaves relate to our respiratory and circulatory systems and the flowers, fruit and seeds to our digestive system and limbs.

When you follow through this concept into nutrition, it becomes apparent that it could make a difference which part of a vegetable you eat. Steiner said that eating root vegetables such as carrots and beetroot can help the thinking, nerve based processes concentrated in our heads, leaves are beneficial for lungs and blood circulation and flowers and fruit for digestion. He further elaborated how this approach could be used to feed animals appropriate food according to whether they are to produce milk, be fattened or for growing calves (Steiner 1993, p.159–66). For example, feeding calves root vegetables, which contain a lot of mineral salts, enables them to develop their nerves and senses in a healthy way. I have not found any modern research that backs up this theory, although a specialist in nutrition science might find some. There is some evidence from traditional practices. For example, chamomile flowers, fruit and fennel seeds are commonly used to help digestion. You might like to experiment with your diet to see if you find any difference from eating these various parts of the plant.

Some scientists did investigate Steiner’s ideas in the early twentieth century, using different methodology from that now required. Eugen Kolisko, a doctor who undertook extensive research, said that the various formative energies in plants are rhythmical and affect the rhythmical processes of the human body (Kolisko 1978, p.30). He found that the blood circulation and its transport of sugar, starch and minerals around the body are particularly affected by the energy rhythms. When you eat fruits they stimulate the rhythms of the digestive system. He said that eating processed sugar has a quite different effect from the sugar in fruits, because it is inert, no longer living. Similarly, the mineral salts in root vegetables stimulate our nerves, consciousness and thinking, but eating a mineral salt such as dolomite does not have that effect.

These concepts could provide an important reason why some people have found a wholefood diet to be beneficial. The nutrients in processed foods may appear to be the same, but they are not, as they do not carry energy rhythms. Bread is made from flour which would lose much of its energies in the milling process. Eating cooked whole grains, which retain these energies, would stimulate the metabolism and limbs, our ‘doing’ energy. Eating fresh green salads stimulates our breathing and blood circulation, keeping us alive and healthy. Root vegetables contain a lot of minerals drawn from the earth. Eating them provides these minerals in a living, dynamic form to stimulate our thinking, our consciousness of who we are. Eating mineral supplements would not have this energetic effect.

The energies in foods can affect not only our physical health but our feelings and behaviour. Maria Geuter, in the introduction to her book, Herbs in Nutrition (1962), describes how children can be assisted to develop more rounded temperaments, through eating particular vegetables and herbs. For example a forceful and overactive ‘choleric’ child can be more amenable if they eat plenty of starchy food and root vegetables. Those foods would accentuate the inactivity and lethargy of a ‘phlegmatic’ child. That child needs a good variety of food including plenty of fresh salads and fruit.

Have you noticed that people living in different areas, on different soils tend to have different physique? I have observed that people born and brought up on clay plains tend to be shorter and stockier than those on sandy areas. I wonder how much this reflects the earth energies in that area and how much the energies in the locally grown food. I recently travelled from New Zealand to England and noticed a difference in the vegetables there – they were thicker, chunkier, more dense, particularly the lettuces. I needed to eat less than in New Zealand. I wondered what caused this difference, whether it was an effect of less light and more earth energies in England, compared to New Zealand. If vegetables grown in different areas have different nutritional effects, this is a factor relevant to the debate about the benefits of eating locally grown food.

Pictorial quality assessment of plant formative forces

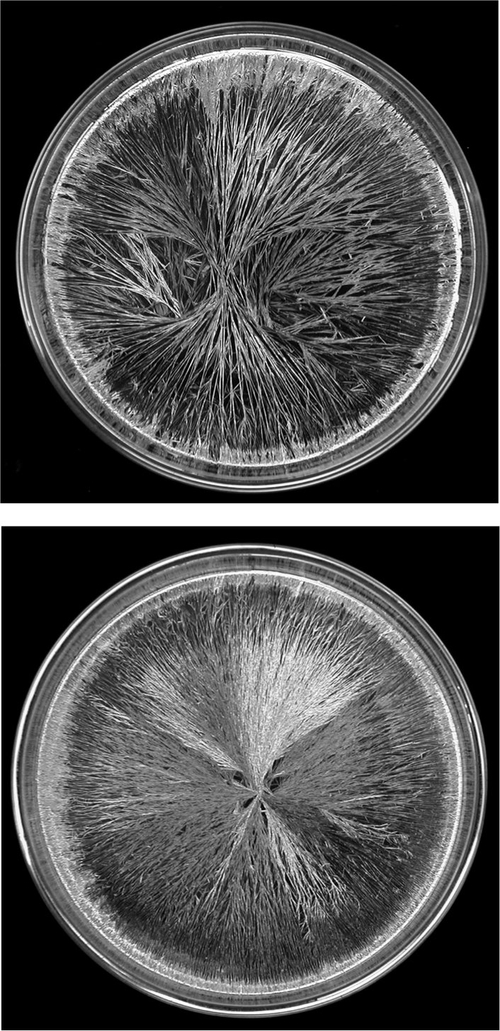

As formative forces in plants cannot be measured in the usual way we need more imaginative ways of assessment. Ehrenfried Pfeiffer (1984) developed a method of showing the formative force content of a plant pictorially by the sensitive crystallisation method. Have you ever noticed the patterns made by hoar frost on window panes? The crystallisation method is similar. Plant sap is added to copper chloride solution and a thin layer is poured on to a glass plate. The plate is kept absolutely still in a chamber designed to eliminate any movement, until the liquid all evaporates, leaving crystals. These crystals are formed in a definite pattern that can be related to the health of the plant and the way it has been grown.

Each plant forms a characteristic pattern of crystals. The method is used quite frequently in Europe to assess food quality. It is also used with human blood and urine to assess health conditions and with animal products such as milk. Dr Ursula Balzer-Graf (1999) claims to tell with 99% accuracy whether milk has been pasteurised or not and whether it comes from a cow on a biodynamic farm or not.

Christian Marcel used this methodology to assess the quality of wines. He was able to show clear differences between different soil types, between wines grown on different soil-types. A further set of pictures showed how well the vines producing the wine-grapes had adapted to the soil and environment (see Figure 7.1). The structure and texture of the crystals provide an indication of the energies in the test material. He emphasised that interpretation of these pictures requires a lot of experience.

An understanding of the formative energies in plants could become an important scientific tool in the future for plant breeders as well as nutritionists. In the following chapter I discuss how observation of formative energies in food plants can be used to indicate their nutritional value.

Figure 7.1: Sensitive crystallisation pictures showing champagne made from grapes. Top: under intensive management; and bottom: under biodynamic management. From Marcel, Sensitive Crystallization (2011), Floris Books, pp. 50, 51, Figures 21, 22.