RADAR RESEARCH AND NAVY INTELLIGENCE

While some women joined the military, worked in untraditional venues, kept farms running, maintained their homes, and supported the war effort through the American Red Cross and USO, Julia F. Herrick, a biophysicist working at Mayo Clinic, was invited by the US War Department to conduct research on radar. In 1942, she was granted a leave of absence by Mayo Clinic to allow her to become a civilian working at the Army Signal Corps Engineering Laboratories in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. During her nearly three years of research, she was also assigned to the radio direction finding receiver subsection of the equipment subsection at the Evans Signal Laboratory at Bradley Beach, New Jersey.

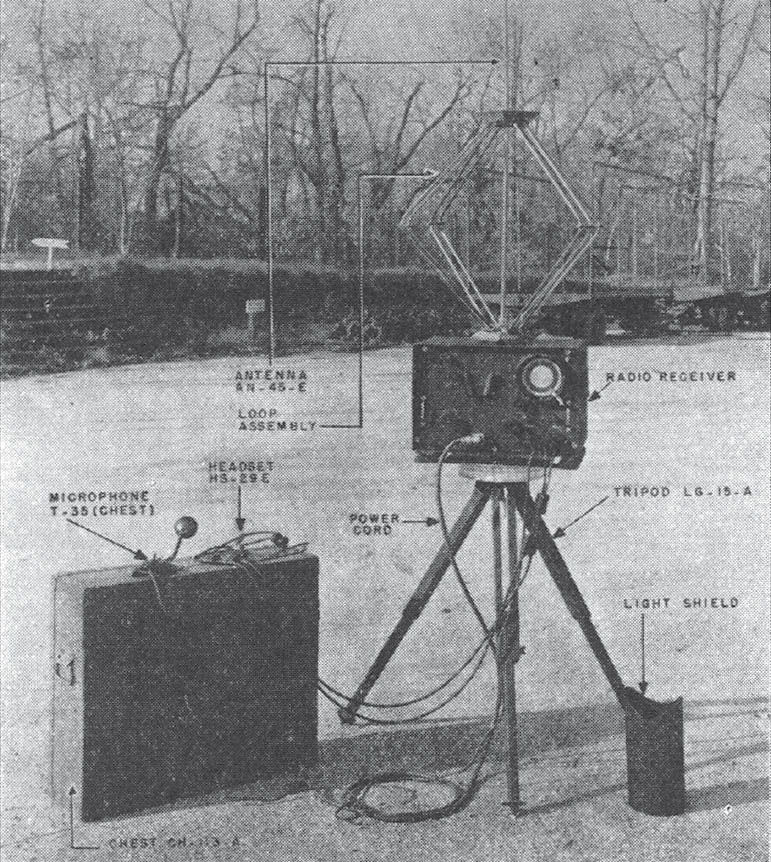

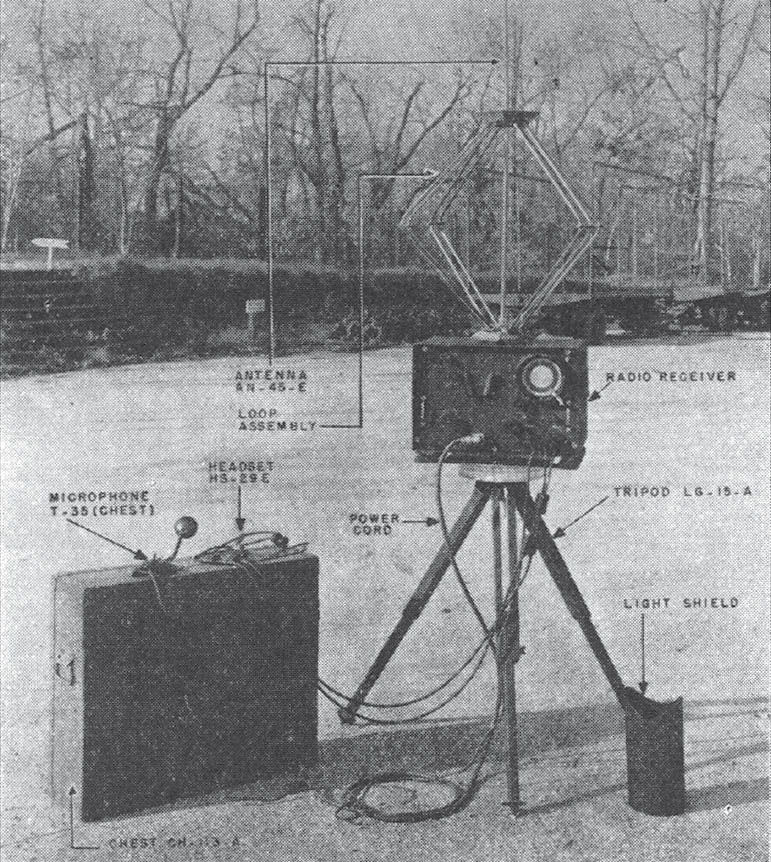

Dr. Herrick’s research focused on radio direction finding, which allowed military units to determine their own locations and to find enemy transmissions. Her team was charged with designing a direction finder that could be transported in a small vehicle and of a size and weight three men could set up and make operational within twenty minutes. Development began in August 1943 and concluded in August 1945. The project was successful for its intended use of radiocommunication direction finding, and she and her team found that “it may also have important application to homing and navigation for position finding for rescue operations.”

· · · · ·

Julia Herrick’s path to radar research began early in her career. She was born in 1893 in North St. Paul. After completing a bachelor’s degree in math from the University of Minnesota in 1915, Julia taught high school math, chemistry, and physics in Pine City and Ely, and in Minneapolis at a private high school later known as Blake School. She returned to the University of Minnesota, and in 1919, after completing a master’s degree in physics, she became head of the physics department at Rockford College, Illinois.

Frustrated by the lack of funding for her lab and changes in the curriculum that discouraged students from taking physics, Julia applied to Mayo Clinic. In 1927, she was accepted as a fellow in biophysics there. By 1931, she had completed her doctorate and became an associate in experimental surgery and pathology, conducting research in Mayo’s Institute of Experimental Medicine. She studied the impact of ultrasound on bone and made important contributions to the development of the thermistor, a device used for physiologic thermometry by biophysicists, anesthesiologists, and experimental surgeons. She had thirteen years of experience working in the field of biophysics when the war broke out.

Julia F. Herrick and her team helped design this direction finder radar unit. Institute of Radio Engineers, © 1949 IEEE. Reprinted, with permission, from L. J. Giacoletto and Samuel Striber, “Medium-Frequency Crossed-Loop Radio Direction Finder with Instantaneous Unidirectional Visual Presentation,” in Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers, September 1949

When Dr. Herrick first arrived at Fort Monmouth, she was assigned to a technician with a few college credits and a couple of years’ experience in electronics, Gustav Shapiro. He said Julia “was a fish out of water, but a smart woman. She had a lot of mathematics, and that’s why they assigned her to me. She was able to supplement what I didn’t know. I started to work on cavity resonators (what did I know about cavity resonators?). I had the feel, but not the mathematics. Between the two of us, we managed to figure things out.”

Gustav Shapiro also got to know her personally and learned about her background:

Dr. Herrick came from a Minneapolis banking family. There were three children, two sons and she was the daughter. When the father died, he left control of the bank to her because he trusted her common sense more than that of his sons. She was a smart gal in her late forties I would say, and prematurely gray. She was an extremely good looking and appealing woman and it was very easy to get along with her. She had the common touch. We once had a Thanksgiving party at our house and played charades. When it was her turn to act out something, she took a long-stemmed flower in her hand and stretched out on the floor facing the ceiling with her eyes closed. She was enacting [a nineteenth-century minstrel song]. She was a regular person.

Dr. Herrick was considered an excellent, hardworking member of the signal corps research team. By all accounts, she was a dedicated, strong woman, and yet on September 13, 1944, Dr. Herrick reported to the infirmary “nervous and crying” after being notified that her nephew, a paratrooper, had been killed in the Normandy invasion.

Dr. Herrick’s tenure in the radio direction finding branch of the Eatontown Signal Laboratory at Fort Monmouth lasted from her appointment in May 1942 to June 1946. Her job title was radio engineer. Another engineer, Julius Rosenberg, who had recently graduated from City College of New York with a degree in electrical engineering, was hired by the signal corps in 1940. In 1942, the same year Dr. Herrick arrived at Fort Monmouth, Rosenberg was assigned to Fort Monmouth as an engineer inspector. He was fired in February 1945 for suspected membership in the Communist Party. Rosenberg was later accused of running a spy ring, and two other engineers also working at Fort Monmouth fled to the Soviet Union. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted of federal espionage charges. They were executed in 1953.

After returning to Mayo Clinic in 1946 from her military assignment, Dr. Herrick continued research on the biological effects of microwaves, ultrasound, physiologic thermometry, and the circulation of blood. She began to study engineering as well. She joined the Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) and became the first editor for the Medical Electronics Professional Transactions. Throughout her career, she published more than 130 articles and attained full professor status at Mayo Clinic. After retiring from the clinic in 1958, at age sixty-five, Dr. Herrick began working for NASA in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, contributing to its space research programs during the first years of its formation until 1965, when she returned to the Midwest and continued working in the medical field until her death in Rochester in 1979.

Julia Herrick, Mayo Clinic biophysicist. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved.

While Dr. Herrick was on the East Coast working with the Army Signal Corps, Veda Ponikvar became one of eighty-one thousand women to join the navy in the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES). She was assigned to analytical and intelligence work in Washington, DC. Veda was born in Chisholm, Minnesota, a small town on the Iron Range, in 1919. Her father was a miner, and her mother was a homemaker. Veda enlisted in March 1943 and was sent to officers’ training at Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts.

The officer who interviewed Veda noted that she was “a rather heavy-set young woman of Slavic origin, [but] her personality makes one unaware of an average appearance. She was a member of several honorary societies, and culminated a college career of activities and debating by being made editor of the year book. This is an outstanding honor at Drake and carries with it a full tuition scholarship.” The interviewer also marked attributes on the “personality appraisal sheet,” noting that Veda’s grooming was inconspicuous and in conversation her volubility was well regulated, not rambling or garrulous. On a personality scale of 4.0 to 2.0, she was given the moderately high score of 3.5.

Veda had been the editor in chief of the Chisholm Tribune Herald at the time she enlisted. She set editorial policy and wrote all of the editorials. She was in charge of the reporters and press employees. She wrote several sections of the weekly paper. She had also been the representative for the Sixtieth Legislative District in Minnesota, temporarily replacing a male senator who was in the armed forces. In that role, she was a member of the committees for rehabilitation, labor, and rules and taxation. Perhaps her most valuable credential was her competency in languages. Veda was able to read, write, interpret, and speak fluently in six foreign languages, including several Slavic languages, French, and German.

After completing the eight-week navy officers’ school at Smith, Veda’s first assignment was in the Office of Procurement and Material in Washington, DC. In that role, she was the editor of secret publications and in charge of other writers. After two months, she was transferred to the foreign branch of naval intelligence. In this position, Veda was the chief analyst of morning conferences and head of the Yugoslav and Albanian desks. During the time she was in this role, the region known as Yugoslavia was contentious, fraught with internal conflict as well as having been defeated early in the war by Hitler. The Allied forces wanted to regain the region. Veda served as an interpreter and oriented naval attachés assigned to posts in Slavic regions. During this fourteen-month assignment, she was frequently involved in security updates given directly to President Roosevelt at the White House. Once when she arrived, the president asked how the WAVES managed to keep their ties so straight. Veda replied, “Mr. President, I cannot tell you. It is a Navy secret.”

As the war in Europe began to wind down toward the end of 1944, Veda was reassigned to the office of the inspector of naval material in Detroit, Michigan. There she was the transportation and assistant security officer, in charge of transportation priorities. She also assisted in security and was a member of the coding board.

Veda’s active status ended in August 1946. She was interested in continued service and so remained on inactive status but not officially discharged in the event her skills would be needed. She was not discharged until 1959. Her extended discharge date might also have related to the classified nature of her work. The navy was known to keep personnel and records secret by extending discharge dates.

Upon her return to Minnesota, Veda, who had wanted to run a newspaper since she was in fifth grade, started the Chisholm Free Press. Nine years later, she bought the competing paper in town because it was basically run by the mining companies and did not reflect the workers’ perspectives. She said she knew “a newspaper was a powerful force—for good or bad.” She made up her “mind to be positive, but [she’d] be honest.” She’d do her “homework and get [the] facts straight.” She was heavily involved in politics and was considered a formidable influence in the region. Some people said she not only ran the newspaper; she also ran the Iron Range, leading to her nickname: the Iron Lady. Among her accomplishments was her role in establishing the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, to protect a million-acre wilderness from development, including mining. On a smaller scale, but of great importance, was her work in creating a facility for developmentally disabled people. She spent a lifetime committed to helping the underdog.

Veda Ponikvar, navy intelligence. Chisholm War History Committee records, Minnesota Discovery Center, Chisholm

Veda returned to the White House on two occasions, meeting Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, to receive awards for community work and volunteering. In the 1989 movie Field of Dreams starring Kevin Costner, the main character’s obituary is read at the end. Dr. Archibald Graham, the real person upon whose life the movie is based, practiced medicine in Chisholm after his baseball career. When he died in 1965, Veda wrote his obituary and published it in her newspaper. Actor Anne Seymour plays Veda in the movie and reads the obituary.

Veda wrote more than forty-three hundred editorials throughout her career. She said, “Once you get printer’s ink in your veins, you can’t replace it. It isn’t blood—it’s ink.” But in addition to her civic involvement and newspaper work, she was also known for her baking. Her walnut potica was said to be the reason many politicians and three-star generals would appear at events she hosted.

· · · · ·

Another woman who would eventually live in Minnesota worked in navy intelligence in Washington, DC, during the same time that Veda did. A large installation of “code girls” was assigned to decipher German and Japanese code throughout the war. Helen Friedline from Jennerstown, Pennsylvania, worked with the large deciphering machines. Her mother raised her and her three brothers after separating from their father, who was a mine supervisor. The Depression had hit the coal mining town in Pennsylvania hard, like it did the Iron Range in Minnesota. Helen’s family lived in poverty, and food was scarce. Helen did not attend her high school graduation ceremony because she did not have shoes. The school provided a good education, though, and in addition to the core curriculum, Helen learned to play the piano and cello. After graduation, Helen waited tables and worked as a housekeeper for a local woman.

After the United States entered the war, Helen worked for Westinghouse Electric as an armature winder. She and some friends decided to join the navy, where they knew they would receive adequate clothing and food. Helen was assigned to naval communications as an “operator of special equipment. This duty required a high degree of accuracy, alertness, manual dexterity, and some proficiency in record keeping.” The machines were large, filling rooms, and they were loud. Helen suffered hearing loss in her right ear as a result.

Helen was not sure why she was given this post. When she enlisted, she had requested an assignment in nursing. She must have scored well on the enlistment exams, plus the ability to play musical instruments was sometimes correlated with math aptitude.

Whatever the reason, Helen and the other WAVES provided a critical service decoding messages. Helen was described as “a capable, conscientious, willing, and adaptable worker” by her captain in the Naval Communications Annex. The navy booklet containing her record also noted that “The individual was employed in a position of special trust and no further information regarding his duties in the Navy can be disclosed. He is under oath of secrecy, and all concerned are requested to refrain from efforts to extract more information from him.” She received the Navy Unit Commendation award for her service, but it was directed that due to the “nature of the services performed by this unit, no publicity be given to [her] receipt of this award.” Several hundred women worked in the Annex, where armed guards were present outside and inside. Decades later, the assistant chief of staff for the Naval Security Group Command noted that “Never in the history of American intelligence had so many people kept a secret for so long.” It is likely that Helen was working on the famous Enigma code that allowed the US Navy to decode German ciphers.

Another letter sent by the deputy chief of naval communications said, “You may take real pride and satisfaction in the part you have played in bringing about the victory that has come to us. The Navy will always be grateful for your loyalty and devotion to duty.”

During her assignment in Washington, DC, she met a navy pharmacist mate from St. Paul, Minnesota, at the Pepsi Center, where men and women in the service were given refreshments. He was a marine about to deploy on missions against the Japanese in the South Pacific and to rescue POWs in China. They decided if he survived and if she liked Minnesota after spending time there, they would get married, which is what happened. Helen attended Gustavus Adolphus College on the GI Bill and finished a nursing program at Bethesda Hospital in St. Paul. She soon had a son, who years later followed in his parents’ footsteps with an assignment in special operations with the marines during the Vietnam War.