“Yaas,” said the farmer reflectively, “all the I.W.W. fellers I’ve met seemed to be pretty decent lads, but them ‘alleged I.W.W.’s’ must be holy frights.”

In early August 1913, some 2800 men, women and children were camped on an unshaded hill near Marysville, California, on the hop ranch of E. B. Durst, the largest single employer of migratory labor in the state. They came in answer to Durst’s newspaper advertisements for 2700 hop pickers. Many walked from nearby towns and cities. They arrived to find that Durst had deliberately advertised for twice as many pickers as he needed and that living conditions were totally inadequate even for half their number. Some of the people slept on piles of straw rented from Durst at seventy-five cents a week. Others slept in the fields. Nine outdoor toilets provided the only sanitary facilities for the entire group. Irrigation ditches became garbage disposals and the stench in the camps was nauseating. Dysentery spread.

The resulting episode, known as the Wheatland Hop Riot, has been called, “one of the most significant incidents in the long history of labor troubles in California.”1 It was the first such outburst of migratory farm labor in this century which resulted in national publicity. It affected the future of the I.W.W. in California profoundly and aroused some interest in the living and working conditions of agricultural workers in that state.

In addition to the intolerable living conditions, Durst offered ninety cents a hundred weight to the crowd of unskilled laborers he had attracted to the ranch. The going rate that season was $1.00. He held back a ten-cent “bonus” to be paid if the worker stayed through the harvest. He also required “extra clean” picking which further reduced the workers’ earnings.

The men, women, and children started work at four A.M. and often picked crops in 105 degree heat during the day. They went without drinking water since no water was brought into the fields. Durst’s cousin sold lunch wagon lemonade, which could be bought for five cents a glass. Because the stores in surrounding towns were forbidden to send delivery trucks into the camp, the hop pickers were forced to buy their food and supplies at a concession store on the ranch.

Only about one hundred of the workers had at any time been I.W.W. members. About thirty of them immediately formed an I.W.W. local on the ranch to protest the living and working conditions. “It is suggestive,” the official investigation report later stated, “that these thirty men through a spasmodic action, and with the aid of deplorable camp conditions, dominated a heterogeneous mass of 2,800 unskilled laborers in three days.”2

A mass meeting of the workers held three days after their arrival at the ranch, chose a committee to demand drinking water in the fields twice a day, separate toilets for men and women, better sanitary conditions, and an increase in piece-rate wages. Two of the committee, Blackie Ford and Herman Suhr, had been in the I.W.W. free speech campaigns in Fresno and San Diego. Ranch-owner Durst argued with the committee members and slapped Ford across the face with his gloves.

The following day, August 3, the Wobblies called a mass meeting on a public spot they had rented for the occasion. Blackie Ford took a sick baby from its mother’s arms, and holding it before the crowd of some 2000 workers, he said, “It’s for the kids that we are doing this.”3 The meeting ended with the singing of Joe Hill’s parody, “Mr. Block.” While the singing was going on, two carloads of deputy sheriffs drove up with the district attorney from Marysville to arrest Ford. One of the deputies fired a shot over the heads of the crowd to “sober the mob.”4 As he fired, fighting broke out. The district attorney, a deputy sheriff, and two workers were killed. Many were injured, and, as the deputies left, another posse of armed citizens hurried to the ranch.

In the following panic and hysteria, the roads around the ranch were jammed with fleeing workers. Governor Hiram Johnson dispatched five companies of the National Guard to Wheatland “to overawe any labor demonstration and protect private property.”5 Burns detectives rounded up hundreds of suspected I.W.W. members throughout California and neighboring states. Some of them were severely beaten and tortured and kept incommunicado for weeks. One I.W.W. prisoner committed suicide in prison and another went insane from police brutality. A Burns detective was later convicted of assault on an I.W.W. prisoner, fined $1000, and jailed for a year.

At a trial beginning eight months later, Ford and Suhr were charged with leading the strike which led to the shooting and convicted of second-degree murder. They were sentenced to life imprisonment and jailed for over ten years.

In his testimony before the Industrial Relations Commission in San Francisco in 1914, Austin Lewis, the Socialist lawyer who defended Ford and Suhr at the Marysville trial, drew the parallel between conditions in agriculture and those in factory work. He called the Wheatland Riot “a purely spontaneous uprising … a psychological protest against factory conditions of hop picking … and the emotional result of the nervous impact of exceedingly irritating and intolerable conditions under which those people worked at the time.”6 I.W.W. agitation about the Wheatland episode led to an investigation by the newly created Commission on Immigration and Housing in California which made subsequent annual reports on the living and working conditions of migrants. Professor Carleton H. Parker was appointed to make a report on the hop riot and investigate abuses in labor camps.

After Wheatland, the California press denounced both the I.W.W. and the exploiters of farm labor. The conservative Sacramento Bee on February 9, 1914, editorialized:

The I.W.W. must be suppressed. It is a criminal organization, dedicated to riot, to sabotage, to destruction of property, and to hell in general. But it will not be suppressed until first are throttled those conditions on which it feeds. Great employers like Durst who shriek the loudest against the I.W.W. are the very ones whose absolute disregard of the rights of others, and whose oppressions and inhumanities are more potent crusaders to swell the ranks of the I.W.W. than its most violent propagandists.7

In the year following Wheatland, forty new I.W.W. locals started in California. Five national organizers and over one hundred volunteer soapboxers agitated throughout the state. The I.W.W. blanketed California with stickers and circulars urging a boycott of the hop fields until Ford and Suhr were released, and living and working conditions improved. Members were urged to organize on the job and slow down if their demands were not met. Employers charged that the I.W.W. members burned haystacks, drove copper spikes into fruit trees, and practiced other acts of malicious sabotage during this campaign. Although much of the I.W.W. propaganda included a hunched black cat showing its claws, an emblem of sabotage, the stickers condemned such practices. I.W.W. opponents claimed that the propaganda ironically advocated the very acts advised against.

“It is no use appealing to the master’s sense of justice for he has not got any, the only thing left is action on the pocketbook …”8 read an I.W.W. statement of this time. By the end of 1914, the I.W.W. Hop Pickers’ Defense Committee claimed that action on the pocketbook had left the hop crop 24,000 bales short. Three years later, the I.W.W. estimated that their boycott of the hop fields had cost California farmers $10,000,000 a year, while the farmers themselves charged that their total losses were between $15-20,000,000 since 1914.9

Ranch owners like Durst financed their own private police force of gunmen and detectives to eliminate the I.W.W. It cost them an estimated average of $10,000 each a year.10 In addition, a Farmers’ Protective League, organized to see that strikes and riots would never threaten the harvesting of a ripened crop, turned its attention to lobbying with the federal government for federal prosecution of the I.W.W.

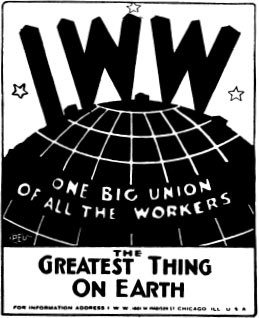

I.W.W. Songbook, Third Edition.

In October 1915, the governors of California, Oregon, Washington, and Utah urged President Wilson to investigate the I.W.W. immediately. They stated:

California, Oregon, Washington, and Utah are experiencing abnormal disorder and incendiarism. These experiences are coincident with threats made by I.W.W. leaders in their talks and publications, and are in harmony with doctrines preached in their publications. Local or state apprehension of ring leaders is impracticable, as their field of activity is interstate…. Through federal machinery covering the whole territory involved, the national government might get at the bottom of this movement…. Exigencies of the situation demand absolute secrecy.11

A Department of Justice agent was sent from Washington to look into these charges, but found that the I.W.W. numbered some four thousand members in California and Washington, and that it was composed “chiefly of panhandlers, without homes, mostly foreigners, the discontented and unemployed, who are not anxious to work.”12 The Farmers Protective League found this a disappointing report.

I.W.W. activity was moving out of the cities onto the farms. Hundreds of thousands of industrial workers left jobless by the 1914 financial depression hopped freights in hope of finding work in the harvest fields. Professor Paul S. Taylor described the situation this way:

In the second decade of the twentieth century, American radicalism in the form of the I.W.W. spread rapidly among these men. It became unsafe to ride the freights unless one carried a “red card.” Farmers learned the meaning of strikes for better wages and working conditions, and responded with vigilante mobs, driving agitators and workers from towns at points of guns. Class warfare broke out in the most “American” sections of rural America.13

Based on over a decade of experience, there developed within the I.W.W. a growing demand to build an organization with a more permanent membership. More than 300,000 Wobbly membership cards had been issued since 1905—but workers often passed through the I.W.W. and did not stay. Usually, I.W.W. branches were “mixed locals” of members from many industries which at times were dominated by the transient workers and at times by the homeguards, the more permanently employed.

In September 1914 the national I.W.W. convention passed a resolution endorsing a conference of representatives from I.W.W. agricultural workers’ locals. This meeting, held in Kansas City in April 1915, organized the Agricultural Workers’ Organization, with headquarters in Kansas City. The A.W.O. was called No. 400 in reference to Mrs. Astor’s ballroom, to indicate that, “the new union was being formed by the elite of the working class.”14

The A.W.O. was set up initially to improve working conditions in the 1915 harvest season. But it proved so effective that it continued as a branch of the I.W.W. for several years. It was the first union to organize and negotiate successfully higher wage scales for harvest workers. It was one of the most dramatic union efforts ever to appear on the American scene.

Practical policies met the problems of organizing the wheat industry, in which thousands of farmers over a vast region hired seasonal workers. The most novel innovation was that of the “job delegate system,” a mobile set of organizers who worked on the jobs, starting at the Mexican border in the early spring and winding up in the late fall in the Canadian provinces. Each local could nominate job delegates who reported regularly to the A.W.O. general secretary. It was the job delegate system of volunteer organizers who “carried the entire office in their hip pocket”—application cards, dues books, stamps, and Wobbly literature—that enabled the organization to spread so rapidly in the wheat fields. One of the job delegates described the opening drive for A.W.O. members in 1915:

With pockets lined with supplies and literature we left Kansas City on every available freight train, some going into the fruit belts of Missouri and Arkansas, while others spread themselves over the states of Kansas and Oklahoma, and everywhere they went, with every slave they met on the job, in the jungles, or on freight trains, they talked I.W.W., distributed their literature, and pointed out the advantage of being organized into a real labor union. Day in and day out the topic of conversation was the I.W.W. and the new Agricultural Union No. 400…. Small town marshals became a little more respectful in their bearing toward any group who carried the little red card, and the bullying and bo-ditching shack had a wonderful change of heart after coming in contact with No. 400 boys once or twice. As for the hijacks and the bootleggers, one or two examples of “direct action” from an organized bunch of harvest workers served to show them that the good old days, at least for them, were now over, and that there was a vast difference between a helpless and unorganized harvest stiff and an organized harvest worker. But best of all, the farmer, after one or two salutary examples of solidarity, invariably gave in to the modest request of the organized workers, with the result that the wages were raised, grub was improved, and hours shortened.15

The Kansas City Conference decided to abandon street agitation and soapboxing in harvest towns in favor of conserving energy for on-the-job organizing. An agriculture workers’ handbook stated this new policy:

Waiting in town or in the “jungles” while holding out for higher wages is a poor policy. This tends to help the organized men “on the ‘bum’” while the unorganized do nothing to improve conditions. The place to take action is on the job and it is the only way to get results. Other tactics that are harmful are soapboxing by ignorant or inexperienced members … and throwing unorganized workers off freight trains…. We are out for 100 percent organization, but we must keep the issues of the big struggle constantly in mind and use judgment and foresight. Tactics that have proved successful are: take out organizers’ credentials … line up as many of the crew as possible and then make demands if conditions are not what they should be. The slowing-down process will be found of great help where employers are obstinate.16

“Get on the Job!” and “Never Mind the Empty Street-corners: The Means of Life Are Not Made There!” became the new slogans of the campaign.

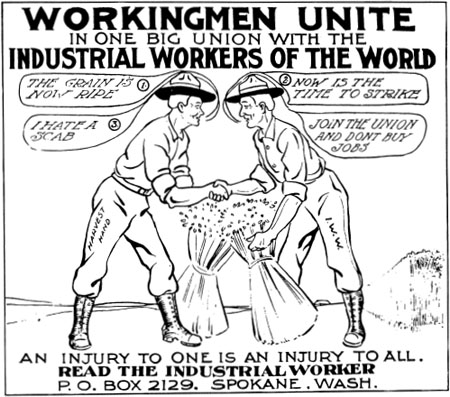

Industrial Worker, August 21, 1913.

The A.W.O. pressed for a uniform wage increase of fifty cents to raise wages to a daily rate of $3.50 in the 1915 wheat harvest. In many areas it was successful. It won its demands through sporadic strikes on the job which became a characteristic form of I.W.W. direct action. Members were instructed to bring other Wobbly crews onto the struck job to strike again if necessary, or effect a slow-down until their wage demands were granted.

Membership expanded to a peak of 70,000 in 1917 as A.W.O. organizers followed the harvest crews into lumber and mining areas to sign up off-season workers. Wherever harvest stiffs met in the Midwest, they sang Wobbly songs. Whenever farm workers had a grievance, the A.W.O. job delegates would be their spokesmen. In some areas cooperative train crews honored the little red membership card as a train ticket and allowed I.W.W. members to move freely from one harvest town to another. The Wobbly card often protected its holder from hijackers and hold-up men who were afraid of molesting an I.W.W. member for fear of incurring the wrath of the organization. Thus the A.W.O. became entrenched in the wheat fields and was regarded as the I.W.W. in the Midwest.

Using the A.W.O. as a model, the 1916 I.W.W. convention set up other industrial branches which absorbed some of the nonagricultural members of the A.W.O. In March 1917, No. 400 was rechartered as Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union No. 110, and restricted solely to organizing agricultural workers. Its members became known as the “one-ten cats.” Despite its depleted membership, the A.W.O. remained the financial backbone of the I.W.W. until about 1925.

From the start of the A.W.O., I.W.W. attempts to recruit farm labor met with organized hostility in some rural communities. Vigilante committees, known as “pick-handle brigades,” sprang up to take care of the “Wobbly menace.” In one small community in South Dakota, for example, the newspaper advised “every member of the vigilante committee over twenty-one to supply himself with a reliable firearm and have it where he can secure it at a moment’s notice.”17 As the nation entered the war, newspaper stories fanned the hysteria of local village and farm groups by repeated exposes of “I.W.W. plots” of widespread sabotage and destruction of property.

In March 1918, Thorstein Veblen drafted a memorandum to the U.S. Food Administration based on an investigation he had made of the availability of farm-labor to harvest wartime crops. He wrote:

These members of the I.W.W., together with many of the workmen who are not formally identified with that organization, set up the following schedule of terms on which they will do full work through the coming harvest season: (a) freedom from illegal restraint; (b) proper board and lodgings; (c) a ten-hour day; (d) a standard wage of $4.00 for the harvest season; and (e) tentatively, free transportation in answering any call from a considerable distance.

These are the terms insisted on as a standard requirement; and if these terms are met, the men propose a readiness to give the best work of which they are capable, without reservation. On the other hand, if these terms are not met in any essential particular, these men will not refuse to work, but quite unmistakably, they are resolved in that case to fall short of full and efficient work by at least as much as they fall short of getting these terms on which they have agreed among themselves as good and sufficient. It should be added that there is no proposed intention among these men to resort to violence of any kind in case these standard requirements are not complied with. Here, as elsewhere, the proposed and officially sanctioned tactics of the I.W.W. are exclusively the tactics of nonresistance, which does not prevent occasional or sporadic recourse to violence by members of the I.W.W. although the policy of nonresistance appears, on the whole, to be lived up to with a fair degree of consistency. The tactics habitually in use are what may be called a nonresistant sabotage, or in their own phrasing, “deliberate withdrawal of efficiency,” in other words, slacking and malingering….

They will, it is believed, do good and efficient work on the terms which they have agreed to among themselves. They are, it is also believed, deliberately hindered from moving about and finding work on the terms on which they seek it. The obstruction to their movement and negotiations for work comes from the commercial clubs of the country towns and the state and municipal authorities who are politically affiliated with the commercial clubs. On the whole, there appears to be virtually no antagonism between employing farmers and these members of the I.W.W., and there is a well-founded belief that what antagonism comes in evidence is chiefly of a fictitious character, being in good part due to mischief-making agitation from outside.18

The fear that I.W.W. strikes in mining and lumber during the war years would spread to agriculture, led to stepped-up legal and extra-legal suppression. The federal government banned strikes in those industries which were “vital to national defense”—including mining, lumber, and agriculture. In July 1917, sixty I.W.W. organizers were arrested in Ellensburg, Washington, and charged with “interfering with crop harvesting and logging in violation of Federal statutes.”19 In the same month, army officers in South Dakota announced that they knew of a state-wide plot to destroy South Dakota’s crops and that Wobbly organizers were ready to set fire to the fields when a certain signal was given. Vigilante violence and a wave of arrests greeted this announcement. Headlines in the Morning Republican in Mitchell, South Dakota, read: “Shotguns Will Greet Any Attempts of I Won’t Workers To Destroy Ripened Grain Crops.”20 The newspaper story stated, “Any of them who attempt to carry out the threat of wholesale crop destruction will be roughly handled and will be lucky if they escape with their lives.”21

In many towns, I.W.W. members were arrested for loitering, for riding trains without having tickets, and on various other charges. Troops and vigilante groups raided I.W.W. headquarters, burned records, and smashed and destroyed furniture and other property.

In addition to mass arrests and vigilante activity, the local authorities attempted to suppress I.W.W. activities by recruiting less militant types of labor for farm work. Women and young boys were enlisted to work in the harvest fields throughout 1917 in anticipation of a labor shortage. Mexicans and Indians from the reservations were used in California. Chambers of commerce, working with the employment service set up by the U. S. Department of Labor, recruited and screened farm laborers. “County Councils for Defense,” organized by county agricultural agents and farmers to handle harvest workers, were started during 1917. “Work or fight” orders were sent to men in the fields who, for one reason or another, balked at living or working conditions.

In California, where the I.W.W. had conducted a successful strike among vineyard workers near Fresno in early 1917, a roundup of I.W.W. members and leaders was launched in the fall of that year. Based on a story in the Fresno morning paper describing charges of I.W.W. sabotage on local growers, the I.W.W. hall in Fresno was raided. Over one hundred men were seized, and nineteen were arrested. Later raids and arrests were carried out in Stockton, Hanford, and elsewhere in the state. The round-up continued throughout the rest of the year. Farmers having labor trouble were directed to get help at a U. S. Department of Justice office in Fresno.

Finally, the Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union was completely disorganized when the federal government cracked down on the I.W.W. in the fall of 1917 and arrested more than one hundred Wobblies around the country on charges of violating the federal Espionage Act.

Legal suppression of the I.W.W. continued during the postwar period. Throughout the country, I.W.W. organizers and members were arrested and jailed under the terms of state syndicalism laws passed as postwar emergency measures. Postwar demobilization and unemployment created a surplus labor supply which further weakened the union organization.

However, meeting in September 1920, the “one-ten cats” resolved to launch another organizing drive in the Midwest wheat fields. They had spotty success. In Colby, Kansas, for example, Wobbly harvesters controlled the town’s labor supply for a week when they collectively refused to work at the going wage rates. In some areas the harvest drive was quite successful through the mid-twenties. Elsewhere, however, mechanized harvesters were replacing mobile harvest hands. The combine, developed as a labor-saving device during the war, cut and threshed grain in a single operation. Five men did the work of 320. As Paul Taylor wrote:

As the use of the combine spread, migratory labor declined, and with it labor radicalism and the social problems caused by a great male migration disappeared from the harvest fields. When radicalism came again to the Middle West it was the farmers who agitated and organized, not the laborers.22

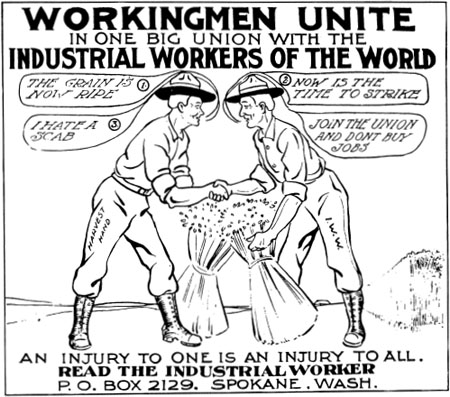

Industrial Worker, February 13, 1913,

These verses were printed in the third edition of the I.W.W. songbook. Little is known about Walquist except that he was the author of a popular I.W.W. pamphlet, The Eight Hour Work Day: What It Will Mean and How to Get It.

(Tune: “My Wife Went to the Country”)

It was on a sunny morning in the middle of July,

I left in a side-car Pullman that dear old town called Chi.

I got the harvest fever, I was going to make a stake,

But when I worked hard for a week I found out my mistake.

Chorus

I went to the country, Oh! why? Oh! why?

I thought it best, you know; the result nearly makes me cry,

For sixteen hours daily, Oh! say; Oh! say;

John Farmer worked me very hard, so I’m going away.

When I left that old farmer he cussed me black and blue;

He says, “You gol durned hoboes, there’s nothing will suit you,”

So back to town I’m going, and there I’m going to stay.

You won’t catch me out on a farm; no more you’ll hear me say:

Chorus

I went to the country, Oh! why? Oh! why?

I thought it best you know; the result nearly makes me cry.

For sixteen hours daily, Oh! say; Oh! say;

John Farmer worked me very hard; so I am going away.

Now the Industrial Workers, they have put me wise;

They tell me I won’t need a boss if the slaves will organize.

They’re all a bunch of fighters; they’ll show you where they’re right.

So workingmen, come join their ranks and help them win this fight.

Chorus

Then we’ll own the country, Hurrah! Hurrah!

We’ll set the working millions free from slavery;

We’ll get all that we produce, you bet! you bet!

So, workingmen, come organize along with the rest!

2

These verses by Ed Jorda appeared in the Industrial Worker (October 3, 1912).

(Tune: “Yankee Doodle”)

A farmer boy once worked in town,

He thought to make a fortune;

The bosses cut his wages down

By capitalist extortion.

Chorus

The I.W.W. waked him up

By preaching class communion,

Said fire the bosses all corrupt

By forming One Big Union.

He thought to get another job

And so regain his losses,

But found it was the same old rob

And by the same old bosses.

He then returned unto the farm,

Perhaps you think it funny;

The farmer boy did all the work—

The boss got all the money.

This farmer boy then came to see

The need of class communion.

Went like a man and paid the fee

And joined the One Big Union.

He joined in with a mighty throng;

I know you think it funny.

He only worked just half as long

But got just twice the money.

So they in winning full control

Depend on class communion.

Demand the earth from pole to pole,

All bound in One Big Union.

Mortimer Downing (1862- ? ) a former editor of the Industrial Worker, was a member of the I.W.W. Construction Workers’ Industrial Union No. 310. He was a chemist and assayer by trade. Convicted in the 1918 federal trial of I.W.W. members in Sacramento, California, Downing was one of the leaders of the “silent defenders,” the group of I.W.W. prisoners who refused to testify before the court. After his release from prison, he took an active part in writing publicity to obtain the release of I.W.W. members who had been arrested in California under the state criminal syndicalism law. Downing’s account of the Wheatland Hop Riot appeared in Solidarity (January 3, 1914).

Bloody Wheatland is glorious in this, that it united the American Federation of Labor, the Socialist Party and the I.W.W. in one solid army of workers to fight for the right to strike.

Against the workers are lined up the attorney general of the state of California, the Burns Agency, the Hop Growers’ Association, the ranch-owners of California, big and little business and the district attorney of Yuba County, Edward B. Stanwood. For the army of Burns men, engaged in this effort to hang some of the workers, somebody must have paid as much as $100,000. The workers have not yet gathered $2,000 to defend their right to strike.

Follow this little story and reason for yourself, workers, if your very right to strike is not here involved.

By widespread lying advertisements Durst Brothers assembled twenty-three hundred men, women and children to pick their hops last summer. A picnic was promised the workers.

They got:

Hovels worse than pig sties to sleep in for which they were charged seventy-five cents per week, or between $2,700 and $3,000 for the season.

Eight toilets were all that was provided in the way of sanitary arrangements.

Water was prohibited in the hop fields, where the thermometer was taken by the State Health Inspector and found to be more than 120 degrees. Water was not allowed because Durst Brothers had farmed out the lemonade privilege to their cousin, Jim Durst, who offered the thirsting pickers acetic acid and water at five cents a glass.

Durst Brothers had a store on the camp, and would not permit other dealers to bring anything into the camp.

Wages averaged scarcely over $1 per day.

Rebellion occurred against these conditions. Men have been tortured, women harassed, imprisoned and threats of death have been the portion of those who protested.

When the protest was brewing, mark this: Ralph Durst asked the workers to assemble and form their demands. He appointed a meeting place with the workers. They took him at his word. Peaceably and orderly they decided upon their demands. Durst filled their camp with spies. Durst went through the town of Wheatland and the surrounding country gathering every rifle, shot gun and pistol. Was he conspiring against the workers? The attorney general and the other law officers say he was only taking natural precautions.

When the committee which Ralph Durst had personally invited to come to him with the demands of the workers arrived, Durst struck the chairman, Dick Ford, in the face. He then ordered Dick Ford off his ground. Dick Ford had already paid $2.75 as rental for his shack. Durst claims this discharge of Ford broke the strike.

This was on Bloody Sunday, August 3, 1913, about two o’clock in the afternoon.

Ford begged his fellow committeemen to say nothing about Durst’s striking him.

At 5:30 that Sunday afternoon the workers were assembled in meeting on ground rented from Durst. Dick Ford, speaking as the chairman of the meeting reached down and took from a mother an infant, saying, “It is not so much for ourselves we are fighting as that this little baby may never see the conditions which now exist on this ranch.” He put the baby back into its mother’s arms as he saw eleven armed men, in two automobiles, tearing down toward the meeting place. The workers then began a song. Into this meeting, where the grandsire, the husband, the youth and the babies were gathered in an effort to gain something like living conditions these armed men charged. Sheriff George Voss has sworn, “When I arrived that meeting was orderly and peaceful.” The crowd opened to let him and his followers enter. Then one of his deputies, Lee Anderson, struck Dick Ford with a club, knocking him from his stand. Anderson also fired a shot. Another deputy, Henry Dakin, fired a shot gun. Remember, this crowd was a dense mass of men, women and children, some of them babies at the breast. Panic struck the mass. Dakin began to volley with his automatic shot gun. There was a surge around the speaker’s stand. Voss went down. From his tent charged an unidentified Puerto Rican. He thrust himself into the mass, clubbed some of the officers, got a gun, cleared a space for himself and fell dead before a load of buckshot from Henry Dakin’s gun.

Thirty seconds or so the firing lasted. When the smoke cleared, Dakin and Durst and others of these bullies had fled like jack rabbits. Four men lay dead upon the ground. Among them, District Attorney Edward T. Manwell, a deputy named Eugene Reardon, the Puerto Rican and an unidentified English lad. About a score were wounded, among them women.

Charges of murder, indiscriminative, have been placed for the killing of Manwell and Reardon. This Puerto Rican and the English boy sleep in their bloody graves and the law takes no account—they were only workers.

Such are the facts of Wheatland’s bloody Sunday. Now comes the district attorney of Yuba County, the attorney general of the state of California and all the legal machinery and cry that these workers, assembled in meeting with their women and children, had entered into a conspiracy to murder Manwell and Reardon. They say had no strike occurred there would have been no killing. They say had Dick Ford, when assaulted and discharged by Durst, “quietly left the ranch, the strike would have been broken.” What matters to these the horrors of thirst, the indecent and immodest conditions? The workers are guilty. They struck and it became necessary to disperse them. Therefore, although they, the workers were unarmed and hampered with their women and children, because a set of drunken deputies, who even had whisky in their pockets on the field, fired upon them, the workers must pay a dole to the gallows.

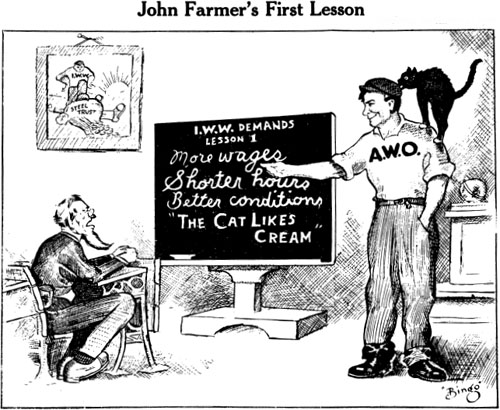

Solidarity, September 2, 1916.

To vindicate and establish this theory an army of Burns men have been turned loose. They took one Swedish lad, Alfred Nelson, carried him around the country through six jails, finally beat him brutally in a public hotel in the city of Martinez. One of these Burns thugs is now under a sentence of a year in jail and $1,000 fine for this act.

These same Burns men arrested Herman D. Suhr in Prescott, Arizona. He was confined like a beast in the refrigerator of a box fruit car. These Burns men poked him with clubs and bars to keep him awake. He was taken to Los Angeles and tortured in that jail. Thence they carried him to Fresno for further torture. Thence to San Francisco, thence to Oakland. Here for four days three shifts of Burns men tortured him by keeping him awake. In order that no marks should show on his person, they rolled long spills of paper and thrust the sharp points into his eyes and ears and nose every time his tired head dropped. He was placed in a three-foot latticed cell so that these animals could easily torture him without danger from his fists. He went crazy, signed a “confession,” and the judges of Yuba and Sutter counties and the district attorneys thereof have tried to make it impossible for him to even swear out a warrant for his torturers.

Mrs. Suhr’s wifehood was questioned when she first visited her husband.

Edward B. Stanwood, the present district attorney of Yuba County, has had more than a score of men arrested. He has kept them for months in jails at widely separated points. Burns men have been permitted to enter their cells and use every effort to frighten them into confessions. Men say they have been brought before Stanwood, himself, and when they told the truth about their actions these Burns men have called them “God damned liars.” Stanwood has sat by. Again and again Stanwood has refused to take any action concerning Durst’s gathering of arms, concerning the actions of the Burns men. He has refused to put charges against these men until compelled to do so by writs of habeas corpus.

Here were a band of men, all of them armed, many of them drunken, who charged a peaceful meeting endangering the lives of women and children. Stanwood says it was because of a conspiracy among the workers that anybody was killed. None of the workers had arms. All the deputies had pistols and rifles.

In the city of Marysville, where the trials will take place the newspapers constantly allude to the men in jail as fiends. The judge is the life-long friend of the dead Manwell, every juror possible knew the sheriff and the other deputies. They publicly allow them to be called fiends. The acts of the Burns men are excused as necessary. To cinch the whole thing the courts have refused a change of venue. The whole community fears that this case should be tried by a jury not involved directly in the facts.

Under the same law the next strike can be broken in the same way. Let a drunken Burns man or a deputy or strike breaker fire upon strikers, kill some of them and the same method will be used. If only these two workers had been killed the six men now held would be charged with murder. It is only handy and incidental to the movement of the bosses that two of their own were involved, whose deaths enrage their friends. The case is plain, workers. Unite to free these six men or it will be your turn next.

4

These unsigned verses about the Wheatland Hop Riot appeared in Solidarity (August 1, 1914).

(Tune: “Wearing of the Green”)

One day as I was walking along the railroad track,

I met a man in Wheatland with his blankets on his back,

He was an old-time hop picker, I’d seen his face before,

I knew he was a wobbly, by the button that he wore.

By the button that he wore, by the button that he wore

I knew he was a wobbly, by the button that he wore.

He took his blankets off his back and sat down on the rail

Solidarity, September 30, 1916.

And told us some sad stories ’bout the workers down in jail.

He said the way they treat them there, he never saw the like,

For they’re putting men in prison just for going out on strike.

Just for going out on strike, just for going out on strike,

They’re putting men in prison, just for going out on strike.

They have sentenced Ford and Suhr, and they’ve got them in the pen,

If they catch a wobbly in their burg, they vag him there and then.

There is one thing I can tell you, and it makes the bosses sore,

As fast as they can pinch us, we can always get some more.

We can always get some more, we can always get some more,

As fast as they can pinch us, we can always get some more.

Oh, Horst and Durst are mad as hell, they don’t know what to do.

And the rest of those hop barons are all feeling mighty blue.

Oh, we’ve tied up all their hop fields, and the scabs refuse to come,

And we’re going to keep on striking till we put them on the bum.

Till we put them on the bum, till we put them on the bum,

We’re going to keep on striking till we put them on the bum.

Now we’ve got to stick together, boys, and strive with all our might,

We must free Ford and Suhr, boys, we’ve got to win this fight.

From these scissorbill hop barons we are taking no more bluff,

We’ll pick no more damned hops for them, for

overalls and snuff. For our overalls and snuff, for our overalls and snuff

We’ll pick no more damned hops for them, for overalls and snuff.

5

Richard Brazier’s song, “When You Wear That Button,” was printed in the fourteenth edition of the I.W.W. songbook. Brazier, who was a delegate to the founding conference of the I.W.W. Agricultural Workers’ Organization, wrote these verses during the 1915 harvest drive.

(Tune: “When You Wore a Tulip”)

I met him in Dakota when the harvesting was o’er,

A “Wob” he was, I saw by the button that he wore.

He was talking to a bunch of slaves in the jungles near the tracks;

He said “You guys whose homes are on your backs;

Why don’t you stick together with the “Wobblies” in one band

And fight to change conditions for the workers in this land.”

Chorus

When you wear that button, the “Wobblies” red button

And carry their red, red card,

No need to hike, boys, along these old pikes, boys,

Every “Wobbly” will be your pard.

The boss will be leery, the “stiffs” will be cheery

When we hit John Farmer hard,

They’ll all be affrighted, when we stand united

And carry that red, red card.

The stiffs all seemed delighted, when they heard him talk that way.

They said, “We need more pay, and a shorter working day.”

The “Wobbly” said, “You’ll get these things without the slightest doubt

If you’ll organize to knock the bosses out.

If you’ll join the One Big Union, and wear their badge of liberty

You’ll strike that blow all slaves must strike if they would be free.”

6

Pat Brennan (1878–1916) also wrote the frequently reprinted poem “Down in the Mines” (Chapter X). “Harvest War Song” was one of the most popular of the I.W.W. agricultural workers’ songs. The line, “We are Coming Home, John Farmer,” was used as the caption for several I.W.W. cartoons. The “Harvest War Song” was submitted by the prosecution in federal and state trials of I.W.W. members, as evidence of the Wobblies’ intent to destroy the crops if their demands were not met. It was printed in the seventeenth edition of the little red songbook. An earlier shorter version appeared in Solidarity (April 3, 1915).

(Tune: “Tipperary”)

We are coming home, John Farmer; We are coming back to stay.

For nigh on fifty years or more, we’ve gathered up your hay.

We have slept out in your hayfields, we have heard your morning shout;

We’ve heard you wondering where in hell’s them pesky go-abouts?

Chorus:

It’s a long way, now understand me; it’s a long way to town;

It’s a long way across the prairie, and to hell with Farmer John.

Here goes for better wages, and the hours must come down;

For we’re out for a winter’s stake this summer, and we want no scabs around.

You’ve paid the going wages, that’s what kept us on the bum.

You say you’ve done your duty, you chin-whiskered son of a gun.

We have sent your kids to college, but still you rave and shout.

And call us tramps and hoboes, and pesky go-abouts.

But now the long wintry breezes are a-shaking our poor frames,

And the long drawn days of hunger try to drive us boes insane.

It is driving us to action—we are organized today;

Us pesky tramps and hoboes are coming back to stay.

7

Elmer Rumbaugh, whom Ralph Chaplin credited with authoring the song “Paint ’Er Red,” was the author of these verses that appeared in Solidarity (June 2, 1917).

(Tune: “Arrah Wannah”)

To the North Dakota harvest came the wobbly band,

Singing songs of revolution and One Big Union grand,

Old Farmer John sat and cussed ’em—called ’em pesky tramps

Just because they would not work by the light of carbide lamps.

Chorus:

We want more coin; that’s why we join

The One Big Union Grand—

The pork chops for to land.

And Farmer John may cuss and rare

And loudly rave and tear his hair;

But one thing understand:

For shorter hours and better wages

We all united stand.

Now fellow workers all together—Let us organize

Into One Big Fighting Union! When will you get wise?

Can’t you see the bosses rob you of your daily bread?

They half starve you, pay bum wages, with a haystack for your bed.

8

Joe Foley wrote these verses to the tune, “Down in Bom Bom Bay.” They were printed in Solidarity (June 9, 1917).

If you’re tired of coffee an’

Beef stew, hash and liver an’

Come, be a man

Join the union grand;

Come organize with us in harvest land—

Down in harvest land.

Chorus

Down in harvest land

United we will stand,

With the A.W.O.

We’re out for the dough

Out for to make old Farmer John come through

Down in harvest land,

The one big union grand

If Farmer John don’t please us

His machine will visit Jesus,

Down in harvest land.

If you’re sick of bumming lumps,

Bread lines and religious dumps;

When you’re broke

You’re a joke

They tell you Jesus is your only hope,

Down in harvest land.

When the winter comes around

You are driven out of town

You’ve got to go,

In the hail and snow

Cause you wouldn’t line up with us, Bo,

Down in harvest land.

9

These verses by George G. Allen, who wrote the popular “One Big Industrial Union,” were taken from the file of I.W.W. songs and poems in the Labadie Collection. The source is not known.

(Tune: “Along the Rocky Road to Dublin”)

One day a western passenger train in the northern belt of wheat

In the burning summer heat, just stopped in time to meet

A little band of “400” men who were standing by to wait,

For a faster train upon the main and surer than a freight.

Oh scenery, Bo! Oh scenery, Bo! Think while I relate:

Chorus

Along the Industrial Road to Freedom,

They were rolling along, singing a song

Though they fight the shacks they need ’em,

On the transportation lines.

And when the crew came round to collect

They never seemed to care

To try to put the dead head off

Who wouldn’t pay his fare.

For a little direct action

It sure never fails at showing the rails

The spirit of that solidarity that has for its call

An injury to one concerns us all,

Along the Industrial Road to Freedom.

Solidarity, October 14, 1916.

By and by, a hard boiled guy, who was hungry for a lunch,

Confided to the bunch that he’d follow up a hunch;

He led the way to the front of the train and all sat down in seats,

In the dining car where the good things are and ordered all the eats.

Oh jungle, ’Bo! Oh, jungle, Bo! Think of all the sweets.

10

E. F. Doree who wrote this article for the International Socialist Review (June 1915) was a leader in the Agricultural Workers’ Organization and was later sentenced to Leavenworth Penitentiary after the I.W.W. Chicago trial.

The great, rich wheat belt runs from Northern Texas, through the states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South and North Dakotas, into Canada, and not a few will point with pride to the fact that last year WE (?) had the largest wheat crop in the history of this country. But few are the people who know the conditions under which they work who gather in these gigantic crops. It is the object of this article to bring out some of these vital facts.

About the middle of June the real harvest commences in Northern Oklahoma and Southern Kansas. This section is known as the “headed wheat country,” that is to say, just the heads of grain are cut off and the straw is left standing in the fields, while in the “bundle country” the grain is cut close to the ground and bound into sheaves or bundles.

In the headed grain country the average wage paid is $2.50 and board per day, but in the very end of the season $3 is sometimes paid, the increase due to the drift northward of the harvest workers, who leave the farmers without sufficient help. This is not a chronic condition, as there are usually from two to five men to every job.

The board is average, although fresh meat is very scarce, salt meat being more popular with the farmer because it is cheaper. Most of the men sleep in barns, but it is not uncommon to have workers entering the sacred portals of the house. Bedding of some kind is furnished, although it is often nothing more than a buggy robe.

The exceedingly long work day is the worst feature of the harvesting so far as the worker is concerned. The men are expected to be in the fields at half past five or six o’clock in the morning until seven or half past seven o’clock at night, with from an hour to an hour and a half for dinner. It is a common slang expression of the workers that they have an “eight-hour work day”—eight in the morning and eight in the afternoon.

Most of the foreign-born farmers serve a light lunch in the fields about nine o’clock in the morning and four o’clock in the afternoon, but the American farmers who do are indeed rare.

In this section the workers are sometimes paid so much per hundred bushels, and the more they thresh the more they get. On this basis they generally make more than “goin’ wages,”* but they work themselves almost to death doing it. No worker, no matter how strong, can stand the pace long; the extremely hot weather in Kansas proves unendurable. Twenty-five men died from the heat in one day last year in a single county in Kansas.

The workers threshing “by the hundred” must pay their board while the machine is idle, due to breakdown, rain, etc.

About the time that the headed grain is reaped the bundle grain in Central and Northern Kansas and Southern Nebraska is ready for the floating army of harvesters.

Here the wages range from $2 to $2.50 and board per day. They have never gone over the $2.50 mark. Small wages are paid and accepted because thousands of workers are then drifting up from the headed wheat country and because of the general influx of men from all over the United States, who come to make their “winter’s stake.” This is about the poorest section of the entire harvest season for the worker. The following little story is told of the farmers of Central Nebraska:

“What the farmers raise they sell. What they can’t sell they feed to the cattle. What the cattle won’t eat they feed to the hogs. What the hogs won’t eat they eat themselves, and what they can’t eat they feed to the hired hands.”

In Nebraska proper the farms are smaller, as a rule, than elsewhere in the harvest country and grow more diversified crops. Almost every farmer has one or more “hired men,” and for that reason does not need so many extra men in the harvest, but in spite of this, the whole floating army marches up to get stung annually. Most of the “Army From Nowhere” cannot get jobs and have a pretty hungry time waiting for the harvest farther north to be ready.

Industrial Pioneer, July 1924.

The farmers in South Dakota do not believe in “burning daylight,” so they start the worker to his task a little before daybreak and keep him at it till a little after dark. If the farmer in South Dakota had the power of Joshua, he would inaugurate the twenty-four-hour workday.

The wages here range from $2.25 to $2.50 and board per day, while in isolated districts better wages are sometimes paid. A small part of the workers are permitted to spend the night in the houses, but most of them sleep in the barns. Sometimes they have only the canopy of the heavens for a blanket.

As soon as the harvest strikes North Dakota wages rise to $2.75 or $3.50 and board per day, the length of the workday being determined by the amount of daylight.

The improved wages are due to the fact that thousands of harvesters begin leaving the country because of the cold weather, and the fact that the farmers insist on the workers furnishing their own bedding. At the extreme end of the season wages often go up to as high as $4.00 and board, per day.

The board in North Dakota is the best in the harvest country, which is not saying much.

In North and South Dakota no worker is sure of drawing his wages, even after earning them. Some farmers do not figure on paying their “help” at all and work the same game year after year. The new threshing machine outfits are the worst on this score, as the bosses very seldom own the machines themselves and, at the end of the season, often leave the country without paying either worker or machine owner.

This, however, is not the only method used by the farmers to beat the tenderfoot. In some cases the worker is told that he can make more money by taking a steady job at about $35.00 a month and staying three or four months, the farmer always assuring him that the work will last. The average tenderfoot eagerly grabs this proposition, only to find that thirty days later, or as soon as the heavy work is done, the farmer “can no longer use him.” There have been many instances where the worker has kicked at the procedure and been paid off by the farmer with a pickhandle.

The best paying occupation in the harvest country is “the harvesting of the harvester,” which is heavily indulged in by train crews, railroad “bulls,” gamblers and hold-up men.

Gamblers are in evidence everywhere. No one has to gamble, yet it is almost needless to say that the card sharks make a good haul. Quite different is it, though, with the hold-up man, for before him the worker has to dig up and no argument goes. This “stick-up” game is not a small one, and hundreds of workers lose their “stake” annually at the point of a gun.

As is the rule with a migratory army, the harvesters move almost entirely by “freight,” and here is where the train crews get theirs. With them it is simply a matter of “shell up a dollar or hit the dirt.” Quite often union cards are recognized and no dollar charged, and the worker is permitted to ride unmolested.

It is safe to say that nine workers out of every ten leave the harvest fields as poor as when they entered them. Few, indeed, are those who clear $50.00 or more in the entire season.

These are, briefly, the conditions that have existed for many years, up to and including 1914, but the 1915 harvest is likely to be more interesting if the present indications materialize.

The last six months has seen the birth of two new organizations that will operate during the coming summer. The National Farm Labor Exchange, a subsidiary movement to the “jobless man to the manless job” movement, and the Agricultural Workers’ Organization of the Industrial Workers of the World.

The ostensible purpose of the National Farm Labor Exchange is to handle the men necessary for the harvest systematically, but its real purpose is to flood the country with unnecessary men, thus making it possible to reduce the wages, which the farmer really believes are too high. If the Exchange can have its way, there will be thousands of men brought into the harvest belt from the east, and particularly from the southeast. It is needless to say that these workers will be offered at least twice as much in wages as they will actually draw.

News has come in to the effect that the farmers are already organizing their “vigilance committees,” which are composed of farmers, businessmen, small town bums, college students and Y.M.C.A. scabs. The duty of the vigilance committee is to stop free speech, eliminate union agitation, and to drive out of the country all workers who demand more than “goin’ wages.”

Foreign language pamphlets issued by the I.W.W.

Arrayed against the organized farmers is the Agricultural Workers’ Organization, which is made up of members of the I.W.W. who work in the harvest fields. It is the object of this organization to systematically organize the workers into One Big Union, making it possible to secure the much needed shorter workday and more wages, as well as to mutually protect the men from the wiles of those who harvest the harvester.

The Agricultural Workers’ Organization expects to place a large number of delegates and organizers in the fields, all of whom will work directly under a field secretary. It is hoped this will accomplish what has never been done before, the systematization of organization and the strike during the harvest, as well as the work of general agitation.

Both of these organizations intend to function so that the workers in the fields will have to choose quickly between the two. If the farmers win the men to their cause, smaller wages will be paid and the general working conditions will become poorer; if the workers swing into the I.W.W. and stand together, then more wages will be paid for fewer hours of labor. Both sides can’t win. Moral: Join the I.W.W. and fight for better conditions.

Mr. Worker, don’t do this year what you did last, harvest the wheat in the summer and starve in breadlines in the winter.

Let us close with a few “Don’ts.”

Don’t scab.

Don’t accept piece work.

Don’t work by the month during harvest.

Don’t travel a long distance to take in the harvest; it is not worth it.

Don’t believe everything that you read in the papers, because it is usually only the Durham.

Don’t fail to join the I.W.W. and help win this battle.

11

This poem may have been written by T-Bone Slim. In some editions of the I.W.W. songbook it is signed “T-Bone and H,” in others, “T. D. and H.” It first appeared in the seventeenth edition of the I.W.W. songbook.

(Air: “Beulah Land”)

The harvest drive is on again,

John Farmer needs a lot of men;

To work beneath the Kansas heat

And shock and stack and thresh his wheat.

Chorus

Oh Farmer John—Poor Farmer John,

Our faith in you is over-drawn.

—Old Fossil of the Feudal Age,

Your only creed is Going Wage—

“Bull Durum” will not buy our Brawn—

You’re out of luck—poor Farmer John.

You advertise, in Omaha,

“Come leave the Valley of the Kaw.”

Nebraska Calls “Don’t be mis-led.

We’ll furnish you a feather bed!”

Then South Dakota lets a roar,

“We need ten thousand men—or more;

Our grain is turning—prices drop!

For God’s Sake save our bumper crop.”

In North Dakota- (I’ll be darn)

The “wise guy” sleeps in “hoosiers” barn

—Then hoosier breaks into his snore

And yells, “It’s quarter after four.”

Chorus

Oh Harvest Land—Sweet Burning Sand!

—As on the sun-kissed field I stand

I look away across the plain

And wonder if it’s going to rain—

I vow, by all the Brands of Cain,

That I will not be here again.

12

Signed “E. H. H.,” this short story appeared in the Industrial Pioneer (October 1921). The “Palouse,” a French-Canadian word, refers to the grassy hill lands north of the Snake River.

The Palouse Harvest being in its full twelve hour swing, “Rhode Island Red” and I, “Plymouth Rock Whitey,” decided to give the struggling farmers a lift and help them “gather in the sheaves.”

Now, for some reason or other, Red was not as enthusiastic over the harvest work as he should be. He claimed that even if he harvested all the wheat in the country, chances were he would be in the soup line in the winter time.

Whatever becomes of the wheat, he says, is a deep mystery to him, except that he knows Wall Street stores a lot of it up where the stiffs can’t get at it.

Anyhow, we landed in the town of Colfax with Red growling over conditions, bum grub and high prices of the local restaurants. After eating some of their “coffee and at two bits a throw,” we sauntered out on the main street to look for a farmer who wanted a couple of enterprising harvesters.

We were approached by a long, thin individual with close set eyes of the codfish order. He was wearing a disguise of spinach on his chin and inquired in a high pitched voice, “Were ye boys looking fer work?” To which I says: “Yes, we certainly are that!” Red busts in then and asks him how much he pays and how many hours he works.

This seemed to be a leading question, altogether irrelevant and immaterial to the farmer’s point of view. He looks Red over and says, “Guess you boys ain’t looking for work, be you?” With that parting shot he walks away and leaves us standing there like a couple of lost dogs.

Now Red has no diplomacy whatever so I told him to keep his remarks to himself, and the next time I would do the talking.

Then we removed ourselves to another corner as our chin-whiskered friend was pointing at us from across the street and waving his hands in the air. He seemed to be delivering an oration to some of his fellow farmers.

Red says they ain’t really honest to God farmers in this section but are illegal descendants of horse thieves and train robbers and we would be better off if we got the hell out of the Palouse district and into the United States again.

But his brain storm was cut short by another “son of the soil” planting himself in front of us and asking in an oily tone of voice, “Gentlemen, are your services open to negotiations? I need a couple of scientific side hill shockers and thought that you probably would consider a proposition of taking on a little labor.”

I was about to accept his offer of work but Red “horns in” again about the hours and wages and our friend left us with the remark that he thought we were gentlemen when he first sized us up but now he knew different.

He even went as far as to remark that he thought we might be connected up with that infamous organization known as the I.W.W. and ought to be in the county jail and that we better be a lookin’ out or he would get a bunch together with a rope and a bucket of tar and a few flags and show us if we could fool around with a real 102 per cent American and his wheat crop. By Heck! Consarn ye!

I then took Red up an alley and had a short talk with him about keeping out of these arguments and letting me get a word in now and then.

Red agreed to keep quiet next time, but I had very little confidence in Red’s being able to hang onto himself so I steered him into a pool hall and went out on the street by myself.

While walking down the street a bright idea permeated into my “ivory dome” as Red calls it.

You are all aware that when a farmer buys a horse he sizes its muscles up and inquires about the price of it. He don’t ask the horse how many hours he will work a day. That, I surmised, was probably the reason the farmer gets hostile when you ask him how many hours you are supposed to work per day. It is contrary to his purchasing habits.

Putting myself on the same basis as the farm horse I accordingly went into an alley and took off my shirt, rolled back my undersleeves and wrapped a couple of old gunny sacks around each arm.

When I put the shirt on over that rig I had a regular set of arms on that would make the world’s champion strong man turn green with envy. “Now watch me captivate the old farmer,” thought I as I burst into view again on the main stem.

A half dozen farmers were lolling and milling around on the opposite corner admiring each other’s twelve cylinder cars and spitting tobacco juice on the sidewalk.

But they forgot all about the late war and the price Wall Street was going to give them for their wheat when they laid eyes on my muscular arms.

A wild scramble ensued in my direction. One farmer tripped his fellow farmer up and “blood flew freely.” They surrounded me like a bunch of wild Indians with loud howls for me, Plymouth Rock Whitey, 100% to go to work! It kind of reminded me of the old times of work or fight in 1919.

But who was it said that “the best laid plans of mice and men will sometimes land you in the pen”? The sons of Colfax got hold of my shirt in their wild excitement, and tore it off, exposing my gunny sack camouflage.

The Rebel Worker, September 1, 1919.

Now just to show you the inconsistency of mankind, these Palousers got angry. In fact they got violent and if I had not been a good sprinter I fear I would have never lived to tell about this. I left, going strong and decided then and there that a pleasant position circulating among the best people would be preferable to a life of unconventional freedom amongst toilers of the soil.

As for Red, he stuck to his cruder and more common methods of selling himself and eventually found a master. That the results of the bargain were mutually satisfactory cannot be stated unreservedly. However, Red gained some accomplishments that in due season will probably come in handy.

For instance he is now quite as able to see in the dark as in the day. He claims that he owes the accomplishment to his labor in the Palouse country, as they seemed to have no clear conception down there as to just when day stopped and night commenced. At any rate Red has a distinct taste for poultry which, so he says, was highly exacerbated by the sight of fat pullets and the absence of any such from the festive board. Being able to see at night he informs me is one of the first requirements for a poultry dinner.

‘Tis an ill wind that never stirs a chicken feather.

13

Folklorist Archie Green collected the song, “The Big Combine” from Glenn Ohrlin, a working cowboy and traditional musician now living in Mountain View, Arkansas. Ohrlin told Green that he had learned the song in an Oregon bar and that it was written about 1919 by Jock Coleman, a Scotch cowboy and harvest hand around Pendleton, Oregon, who was known as the “Poet Lariat” of that region.

The I.W.W. was frequently mislabeled the Independent Workers of the World, and “The Big Combine” might have been an I.W.W. song. “The Big Combine,” sung by Glenn Ohrlin, is included on a recent LP record, “The Hell-Bound Train,” issued by The University of Illinois Campus Folksong Club. In the notes to that recording, Professor Green states, “To my knowledge, ‘The Big Combine’ has never been collected or published as a folksong. Hence, Glenn’s version is significant as: (1) a traditional document of a by-gone agricultural practice; (2) an addition to the corpus of Wobbly songs collected from a nontrade union oriented singer; (3) a new branch in the already abundant ‘Casey Jones’ family tree.”

“The Big Combine” is set to the tune “Casey Jones.” In this song, as in Joe Hill’s parody, the train engineer is portrayed as anti-union.

Well, come all you rounders that want to hear

The story of a bunch of stiffs a-harvesting here,

The greatest bunch of boys ever come down the line,

Is the harvesting crew on the big combine.

There’s traveling men from Sweden in this grand old crew,

Canada and Oregon and Scotland, too.

I’ve listened to their twaddle for a month or more,

I never saw a bunch of stiffs like this before.

Oh, you ought to see this bunch of harvest pippins,

You ought to see, they’re really something fine,

You ought to see this bunch of harvest pippins,

The bunch of harvest pippins on the big combine.

Well, there’s Oscar just from Sweden, he’s as stout as a mule,

He can jig and dance and peddle the bull,

He’s an Independent Worker of the World as well,

Says he loves the independence but the work is hell.

Well, he hates millionaires and he wants to see

Them blow up all the grafters in the land of liberty,

Says he’s going to leave this world of politics and strife

And stay down in the jungle with his stew can all his life.

Oh, Casey Jones, he knew Oscar Nelson,

Casey Jones, he knew Oscar fine,

Oh, Casey Jones, he knew Oscar Nelson,

He kicked him off the boxcars on the SP line.

Well, the next one I’m to mention, well, the next in line

Is the lad a-punching horses on the big combine,

He’s the lad that tells the horses what to do,

But the things he tells the horses I can’t tell you.

It’s Limp and Dude and Dolly, you get out of the grain,

And get over there, Buster, you’re over the chain,

Oh, Pete and Pat and Polly, you get in and pull,

And get over there, Barney, you durned old fool.

You ought to see, you ought to see our skinner,

You ought to see, he’s really something fine,

You ought to see, you ought to see our skinner,

You ought to see the skinner on the big combine.

Well, I’m the head puncher, you can bet that’s me,

I do more work than all the other three,

A-working my hands and my legs and my feet,

Picking up the barley and the golden wheat.

I got to pull the lever and turn on the wheel,

I got to watch the sickle and the draper and the reel,.

And if I hit a badger hill and pull up a rock,

Well, they say he’s done it, the durn fool Jock.

I’m that lad, I’m the head puncher,

I’m that lad, though it isn’t in my line,

I’m that lad, I’m the head puncher,

I’m the head puncher on the big combine.

*“Goin’ wages” is an expression used by the farmer in answer to the question, “What do you pay?” It really means the smallest wages paid in the country.