I rustled the High Ore

I rustled the Bell

I rustled the Badger

I rustled like hell,

I rustled the Tramway,

I rustled the View

And I finally found work

At the Ella-ma-loo (Elm Orlu).

The early struggles of the Western miners imprinted a militant heritage on the Industrial Workers of the World. Strikes in the gold, silver, copper, and lead camps of the West made revolutionary unionists of the miners as vigilante committees, state militia, and armed mine guards wrecked their homes and halls, locked them in bull pens, and dominated mining towns. Arrests, beatings, individual killings, machine gunning of union meetings imbued the Western miner with a fierce independence characteristic of the reckless and lawless frontier life.

In 1897 the Western Federation of Miners withdrew from the American Federation of Labor, claiming that the A.F.L. had betrayed the miners’ cause. Disillusioned about legal protection from local courts, state legislatures, and the federal government, mine union leaders like Bill Haywood and Vincent St. John became convinced that political action was useless and that direct economic action was the only way to effect a change. As a result, the Western Federation of Miners attempted to broaden its support, first, through spearheading the organization of the Western Labor Union, then the American Labor Union, and finally, the I.W.W.—radical industrial unions that, hopefully, would be able to counter the mine owners’ force with the force of united labor groups.

A strike in Goldfield, Nevada, a goldmining town of some 15,000-20,000 persons, was the first practical test of W.F.M.-I.W.W. cooperation. It failed. The Goldfield strike came in the midst of the 1907 depression, immediately after the Idaho trials of W.F.M. President Charles Moyer, I.W.W. leader Bill Haywood, and a blacklisted miner, George Pettibone. It came at a time when the I.W.W. organization was split over the issue of direct vs political action.

The Goldfield strike was marked by violence, the activities of a hostile citizens’ committee, and martial law. It was complicated by a jurisdictional dispute between the W.F.M. and an A.F.L. carpenters’ union, as well as by a sympathetic strike of miscellaneous town workers organized into an I.W.W. local.

Goldfield became an armed camp. A restaurant owner was killed. The town’s businessmen locked out I.W.W. members. President Theodore Roosevelt sent in federal troops at the mine owners’ request and, on the day the troops arrived, the mine companies cut wages and announced an open shop policy. A commission which investigated the Goldfield situation reported:

The action of the mine operators warrants the belief that they had determined upon a reduction of wages and the refusal of employment to members of the Western Federation of Miners, but that they feared to take this action unless they had the protection of Federal troops and they accordingly laid a plan to secure such troops and then put their program into effect.1

The loss of the strike in Goldfield gave further impetus to the Western Federation of Miners to withdraw from the I.W.W. Growing increasingly more conservative, the officers of the W.F.M. charged that the “propaganda of the spouting hoodlums” had been one of the reasons for the failure of the strike. On the other hand, Vincent St. John and other I.W.W. organizers claimed that the I.W.W. was abused because the union did win important concessions from the mine companies in Goldfield: higher wages, an eight-hour day, and job control. St. John later looked back on the Goldfield strike as a golden age of I.W.W. effectiveness. He recalled:

No committees were ever sent to any employers. The unions adopted wage scales and regulated hours. The secretary posted the same on a bulletin board outside of the union hall, and it was the LAW. The employers were forced to come and see the union committees.2

Butte, Montana, was another setting for the growing hostility between the W.F.M. and the I.W.W. Butte miners had been organized since 1878 in the largest and strongest metal miners’ organization in the West. For a long time they claimed that Butte was “the strongest union town on earth,” where no employment was possible for a man who did not hold a union card. Oral tradition has it that even the two Butte chimney sweeps had their own union and that a local of miscellaneous workers once debated whether to boycott the Butte cemetery in order to help the grave-digger win better working conditions.3

Butte miners helped organize the Western Federation of Miners in 1893 and received the Federation’s first charter. For the next fifteen years they benefited from a divided enemy, as the “copper bosses,” in their wars with one another, encouraged the unions and wooed union leaders.

Dissension started in Butte Miners Union Local No. 1 about 1908, following the withdrawal of the W.F.M. from the I.W.W. Radicals among the Butte miners railed against the position taken by W.F.M. national officers, and factionalism broke out in the open in 1911 when the W.F.M., after fourteen years as an independent union, rejoined the A.F.L.

In 1912 several hundred Finnish Socialist miners were fired by the Butte mining companies. Company officials fumed against proposals, introduced by the Socialists elected to the town’s city council, to tax mine tonnage for the city’s benefit. In an attempt to rid Butte of radicals—for a time the mayor of the town was a Socialist—the Anaconda Copper Company initiated a “rustling card” system.

A miner applied at the company’s central employment department, gave his personal and job history, and a list of references. He waited for several weeks while his references were checked out. If he was cleared, he was given a “rustling card” which gave him access to “rustle the Hill,” that is, to apply directly for work at any of the Anaconda mines and mines of other companies which required the rustling card as a minimum job qualification. When a miner was hired, his card was sent back to the central employment department. If he quit work, he had to reapply at the rustling card office and go through the same procedure. The card could be withheld if the company regarded him “undesirable” for any reason. Only the small Elm Orlu mine, known among miners as the “Ella-ma-loo,” did not require a rustling card. The company’s president held that it was “un-American.”4

The reason for the rustling card was given by an Anaconda Company official in a speech before the Chamber of Commerce in Missoula, Montana, on August 29, 1917. He said:

It became apparent to the officials of the Anaconda Company that in view of the increasing number of such characters [I.W.W.’s and radicals] in Butte, many of whom were working in the mines, that in order to do any part of its duty to the community and to itself it must first establish some system of knowing its employees. This was the main reason for the adoption of the rustling card system.5

The discharge of the Finnish Socialist miners and the adoption of the rustling card system became immediate issues. A committee of Butte Miners Union Local No. 1 recommended no opposition to the rustling card. But the radicals in the union vehemently attacked the rustling card system and were backed up by a referendum vote taken in the local. The issue was carried to the 1912 convention of the W.F.M. Tom Campbell, the leader of the Butte radicals, ran for the office of national union president against the incumbent, Charles Moyer. Campbell lost, 8318 to 3744. The W.F.M. convention rejected his charges that the conservative W.F.M. officials had taken no action in the firing of the Finns and refused to fight the rustling card system.

In turn, the W.F.M. convention expelled Campbell from the Federation for “conduct unbecoming a member of the Western Federation of Miners … by disseminating the lie that the Western Federation of Miners was floundering on the rocks of destruction and was impotent to protect its membership.”6

Dissension in the next few years split the Butte local. Three miners’ unions vied for membership: the older Butte Miners Union (W.F.M.), a radical independent group led by miner “Muckie” Mac-Donald, and a small I.W.W. local. Factionalism culminated in rioting, gunfire, and death when the hall of the Butte Miners Union was dynamited by twenty-six blasts during a visit of W.F.M. President Charles Moyer to the town.

The Butte mayor, a Socialist, charged Moyer’s followers with firing the first shot from the union hall. The editor of the W.F.M. national magazine reported that he had reliable information that the dynamiting had been done by agents from a private detective company in the mine owners’ employ. Professor Paul Brissenden wrote in 1920:

It is not likely that the responsibility for this disaster will ever be definitely fixed. The mine operators place the blame on the shoulders of the agitators and malcontents in the union. The members of the radical unions in the Butte district generally explained it as an act of the mine operators perpetrated in order to discredit the union and if possible disrupt it and so bring about an open shop camp.7

The dynamiting of the Miners’ Hall ended over two decades of Butte’s role as a closed-shop, union town. The mining companies declared martial law. Troops crushed the new organization of radicals, known among miners as “Muckie MacDon-ald’s Union,” and ended job control by the W.F.M. and A.F.L. craft unions as well. MacDonald and Joe Bradley, the officers of the radical group, were sentenced to three to five years for their alleged part in the bombing. The Anaconda Copper Company, by far the largest producer in the town, declared Butte “open shop.”

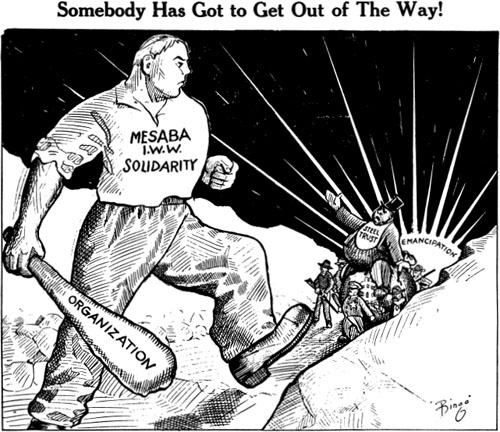

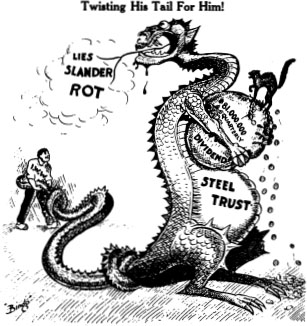

Two years later in 1916, the seventy-mile-long Mesabi Iron Range in northern Minnesota was the setting for a major I.W.W. metal mine strike. Some 7000 to 8000 immigrant miners—Finns, Swedes, and Slavs—who had been brought to the Range in 1907 to scab on striking W.F.M. members, now demanded better wages, shorter hours, and an end to a system of graft practiced by company foremen who elicited “kick-backs” for placing miners on more productive veins of ore.

An unorganized walkout started at the Aurora Mine on June 3 against the Oliver Company, a subsidiary of United States Steel Corporation. The I.W.W. national office responded to a call for help from the miners and sent I.W.W. organizers Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Carlo Tresca, Sam Scarlett, Joe Ettor, and others to the Range. By the middle of June, the entire Range was out on strike.

When the first clash of the strike resulted in the death of a miner, the governor of Minnesota sent an investigator to the Range. He was told by the secretary of the I.W.W. miner’s local: “We don’t want to fight the flag, we don’t want to fight anybody, what we want is more pork chops.”8

A second clash between strikers and deputies resulted in the death of two deputies and led to the arrest of a group of miners as well as the I.W.W. strike leaders. No trial was held. Instead, local legal authorities attempted to make a deal with Judge O. N. Hilton who had been called in by the I.W.W. as defense attorney. Five of the I.W.W. organizers would be released if the other Wobbly prisoners pleaded guilty of manslaughter. Authorities persuaded three Montenegrin miners who spoke little English to plead guilty and sentenced them to prison for terms of one to seven years. Bill Haywood, who had become I.W.W. secretary-treasurer in 1914, charged that the I.W.W. organizers should never have consented to such an arrangement and terminated their connection with the I.W.W. at that time for “breaking solidarity.”

Throughout September the strikes spread to the Cayuna and Vermilion ranges, until a 10 percent wage increase was won and an eight-hour day promised for the following May 1. At the same time, several thousand miles away in Pennsylvania, the I.W.W. agitated for shorter hours and higher pay for anthracite coal miners who had organized about a dozen I.W.W. locals in the region. The strike, which had made some headway in the Lackawanna area, was broken, however, by the activities of the Pennsylvania State Constabulary. Mounted troopers raided a union meeting of 250 miners at Old Forge in June and arrested and jailed all those present. Four months later the prisoners were released because no evidence against them could be found.

Solidarity, August 19, 1916.

In the Southwest, Wobblies stepped up their organizing campaign in Arizona’s four metal mining districts in the fall of 1916. By 1917 their agitation won support from some members of the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (formerly the W.F.M.) and several A.F.L. unions who joined them in a general walkout in June and July 1917. Following the declaration of war in 1917, wages in the copper camps fell far below the wartime price increase in copper. The copper companies met the unions’ demands for wage increases with a consistent refusal to adjust or arbitrate grievances.

The Arizona strike was denounced as “pro-German,” as the companies stockpiled arms and ammunition, organized vigilante committees, hired additional guards and gunmen, and publicly declared their intention of removing labor agitators from the area. The Bisbee, Arizona, sheriff wired the state’s governor that most of the strikers were foreigners, that the strike appeared to be a pro-German plot, and that bloodshed was expected imminently.

On July 6, 1917, a Loyalty League was organized in Globe, Arizona. It resolved

that terrorism in this community must and shall cease; that all public assemblies of the I.W.W. as well as all other meetings where treasonable, incendiary, or threatening speeches are made shall be oppressed; that we hold the I.W.W. to be a public enemy of the United States; that we absolutely oppose any mediation between the I.W.W. and the mine owners of this district; that after settlement … [we are] opposed to employment of any I.W.W. in this district; that all citizens deputized be retained as such.9

Within a few days the Loyalty League circulated application blanks to all citizens in Globe and Miami. They announced: “Every refusal will be noted…. We will take an inventory of the citizenship of the district…. The names of I.W.W. members and sympathizers are wanted.”10 The Loyalty League boycotted those who would not sign.

Four days later, sixty-seven I.W.W. members were rounded up in Jerome, Arizona, forced into cattle cars, and shipped to Needles, California. Two days later the Bisbee Loyalty League surpassed this performance. An organized posse of over 1000 citizens, wearing white handkerchiefs around their arms to identify each other, were deputized by the sheriff. They took over the telegraph office of the town so that no news of the raid would leak out. Rounding up 1200 I.W.W. members, townspeople, and sympathizers, they drove them to a ball park at the edge of town, where a “kangaroo court” asked them to choose between returning to work, arrest, or deportation. Close to 1200 were loaded in groups of fifty into a twenty-seven car cattle train. Guarded by 200 deputies, the train ended up in Hermanas, New Mexico, where the prisoners were kept for thirty-six hours without food before being sent by federal authorities to Columbus, New Mexico. Here they were put into a stockade under army guard and kept until the middle of September, when the camp was disbanded because the federal government refused to continue supplying food.

Most of the deportees returned to Bisbee. Some were arrested; others were allowed to stay unmolested. A year later, a federal grand jury indicted twenty-one leaders of the Bisbee Loyalty League. None was convicted.

The President’s Mediation Commission sent in to settle the strike and investigate the deportations, found that of the 1200 deportees, 381 were A.F.L. members; 426 were Wobblies; and 360 belonged to no labor organization. It also found that 662 were either native-born or naturalized citizens, 62 had been soldiers or sailors, 472 were registered under the Selective Service Act, 205 owned Liberty Bonds, and 520 subscribed to the Red Cross. The foreign-born deportees included 179 Slavs, 141 Britishers, 82 Serbians, and only a handful of Germans.

The copper mining strikes in Arizona were ended by the deportations and by the President’s Mediation Commission which investigated the situation in October 1917. The commission reported that the strikes were neither pro-German, nor seditious, but “appeared to be nothing more than the normal results of the increased cost of living, the speeding up processes to which the mine management had been tempted by the abnormally high market price of copper.”11 Its settlement, however, excluded any miner who spoke disloyally against the government or who was a member of an organization which refused to recognize time contracts. Thus, as Perlman and Taft have written, the commission put the I.W.W. “beyond the pale.”12

The copper companies were protected by the umbrella of the Sabotage Act of 1918, which classified the mines as “war premises” and their output as “war materials.” Army troops which had been sent in during the 1917 Arizona strike were given the authority “to disperse or arrest persons unlawfully assembled at or near any war premise’ for the purpose of intimidating, alarming, disturbing, or injuring persons lawfully employed thereon, or molesting or destroying property thereat.”13

Federal troops stayed in Arizona until 1920 in an effort to curb the “Wobbly menace.” They protected strikebreakers, dispersed street crowds, guarded mine property, broke up public meetings, and patrolled “troublesome” sections of the community. They were billeted in quarters built for them by the mine owners and were brought up-to-date on industrial conditions by reports of private company detectives.

As Perlman and Taft wrote of the I.W.W. and A.F.L. efforts in the Arizona copper camps: “Unionism of either variety failed to survive the experiences of 1917.”14

In June 1917 fire broke out on the 2400-foot level of the Speculator Mine in Butte and killed 164 miners who were smothered or burned to death. It was one of the worst mining tragedies in history. In the words of a Butte miner:

They were caught like rats in a trap by the explosion of gas in the lower levels, the exits of which were blocked by solid concrete bulkheads with no opening in them. The holocaust was the last straw. The miners, galling under abuses and working under conditions which endangered their lives every minute underground, decided to call a halt to this condition of affairs and not return to work until assured by the operators that the conditions would be corrected and the lives of miners fully protected.15

Miners charged that the tragedy was caused by the mine company’s disregard for safety regulations. Trapped on the lower levels, they clawed at concrete bulkheads which the company had built instead of the steel manholes required by the law. Over half of the bodies were so badly burned they were unable to be identified.

Fourteen thousand incensed Butte miners immediately struck for adequate safety provisions in all the mines, an increase in wages, and the absolute abolition of the rustling card system. Under the leadership of Tom Campbell who had run against Charles Moyer in the 1912 W.F.M. convention, an independent Metal Mine Workers Union was formed. The I.W.W. members set up the Metal Mine Workers Industrial Union No. 800, which numbered about 1200 members in 1917.

Again, martial law was declared in Butte. The press screamed “sedition,” “enemy of the government,” and “pro-German,” and once more stereotyped the strike as I.W.W. inspired. Company owners refused to meet the unions’ grievance committees. W. A. Clark of the Clark mining interests declared that he would rather flood his mines than concede to strikers’ demands. The miners held a mass meeting and petitioned the government to take over the mines, “so that the miners may give prompt and practical evidence of their patriotism.” 16 They also lodged a formal protest against the rustling card system with Secretary of Labor Wilson, which led to a later investigation of labor conditions in Butte.

In July the Anaconda Company agreed to an increase in wages, but refused to give up the rustling card system, although holding out the inducement of a “temporary card” which could be used until a miner’s record was fully checked. The strikers refused this offer.

In the early morning of August 1, 1917, a group of gunmen broke into the boardinghouse room of I.W.W. organizer Frank Little. He had been an I.W.W. member since 1906 and was one of the leaders of the Missoula, Spokane, and Fresno free speech fights. A member of the I.W.W. Executive Board, Little had come to Butte from the Mesabi Range. In August 1916 he had been arrested at Iron River, Michigan, taken out of jail, beaten, threatened with lynching, and left unconscious in a ditch with a rope around his neck.

Solidarity, August 26, 1916.

George Tompkins, a Butte miner, told what happened to Little in Butte:

At 3 o’clock in the morning of August 1st, six masked, heavily armed men broke down the door of Little’s room and dragged him from his room in his night clothes, placed him in an auto, and took him to a railroad trestle at the edge of the town, and there hanged him. To his dead body was pinned a card which read, “First and Last Warning—3-7-77,” followed by the first letters of the names of prominent members of the strikers, which indicated that the perpetrators of the crime intended more violence on other members of the strikers.17

The numbers 3-7-77 was the sign used by the old-time vigilantes in Adder Gulch, Montana, to threaten road agents with death. They signified the dimensions of a grave.

Little’s funeral was one of the largest the state had ever seen. The five-mile route to the cemetery was lined with thousands of miners. The Butte Miner of August 6, 1917, wrote:

Funeral paraders in silent protest…. 2,514 in procession in demonstration against lynching…. Remains of Frank H. Little, I.W.W. Board Member, are borne down principal streets of Butte on the shoulders of red-sashed pallbearers marching through solid lanes of many thousand spectators…. Brief services at cemetery.18

A band played the funeral march from Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony.

Gradually, the strikers drifted back to work, accepted small wage increases, and the modified rustling card system. The strike ended in December 1917.

But the federal troops which had been called in the year before, stayed on in Butte until 1921. The head of the Butte “Council of Defense” warned:

The minute the military here stop detaining men for seditious acts we have got to take it into our own hands and have a mob and we don’t want to start that. I can get a mob up here in twenty-four hours and hang half a dozen men.19

Mine owner W. A. Clark stated, “I don’t believe in lynching or violence of that kind unless it is absolutely necessary.”20 While the troops remained at Butte, the Chamber of Commerce reported, “Every businessman … feels perfectly safe.”21

Historian William Preston, the author of a recent study on suppression of radicals during the World War I period, described what followed the end of the 1917 strike:

Anaconda seemed intent on a show down. Its detective informers were high in the ranks of the Butte I.W.W. In violently incendiary speeches, these company provocateurs encouraged their cohorts to adopt a position that the government would define as seditious and disloyal. In other words, the copper company was having its paid agents help organize a wartime strike against itself as a ruse for the indictment and elimination of the local radical menace.22

Professor Preston’s footnote to this information stated, “The special agent of the Bureau of Investigation and United States Attorney Wheeler discovered and reported the existence of these company provocateurs.”23

When the Butte I.W.W. local did strike on September 13, 1918, army troops, swelled by private detectives, local police, and mine officials, raided the I.W.W. hall, the hall of the independent radical Metal Mine Workers’ Union, and the offices and printing plant of the radical newspaper, the Butte Bulletin. They confiscated literature and records, arrested and jailed forty miners, and put the union halls and newspaper office under military guard. In the next few days the army arrested seventy-four additional miners without warrants, charged them with sedition, and held them for investigation by the Department of Justice. All but one were later released for lack of evidence on which charges against them could be made.

The Butte I.W.W. strike culminated in April 1920 with the incident called the “Murder of Anaconda Hill,” in which mine guards armed with rifles and machine guns, fired on pickets marching in front of the Neversweat Mine. Fourteen strikers were wounded and one man was killed. The Butte Daily Bulletin issued an extra edition a short time after the shooting. The newspaper had the following headline set in 96 point type. This, it charged, was the order mine company officials had given to the guards:

The newspaper edition, as well as the Butte I.W.W. strike, was suppressed.

1

In 1913 and 1914, Ralph Chaplin wrote a series of poems, signed “by a Paint Creek Miner” which he sent to the International Socialist Review. In his autobiography, Chaplin wrote: “At the time we had moved to Westmoreland [W. Va.], the daily papers were carrying stories about the strike in Kanawha County, but they were far from being of headline importance. Even at meetings of the Socialist local, little attention was then given to that strike. It had started in 1911 as a spontaneous unorganized protest against an accumulation of grievances. The officials of the miners’ union [U.M.W.] ignored it. After months of neglect and inattention it was discovered that the smoldering discontent was assuming ominous proportions. That was just about the time I became associate editor of the Labor Star [Huntington (W. Va.) Socialist and Labor Star]. At this stage the mine-owners were preparing to reinforce their private guards with state militia and with professional gunmen recruited through the Baldwin-Felts agency. From that time on reports of the slugging and manhandling of miners began to trickle through. Then came stories of skirmishes and shooting on both sides …

Solidarity, September 9, 1916.

”In spite of a budding desire to be objective and ‘constructive,’ my passion was aroused by the brutalities of the strike … The inadequacy of strike relief and of publicity seemed to me inexcusable. The horrible conditions in Kanawha County were not arousing indignation beyond the borders of the state. One or two of my ‘Faint Creek Miner sonnets had been reprinted in the Review and the Masses. Beyond that, to my knowledge, no word was reaching the outside world. In the strike zone, however, one of my sonnets, a vitriolic thing titled ‘Mine Guard? created a sensation. Someone with a rare sense of recognition tacked it on Captain Fred Lester’s door … At that time Lester was decidedly unpopular with the miners. He had just been promoted from the state guard to a captaincy in the Baldwin-Felts outfit.

“This incident which transformed the situation from a strike into a small scale civil war was the ‘Bull Moose Special.’ We were tipped off in Huntington that an armored train was being rigged up at the Chesapeake and Ohio yards for use against the miners … We spread a warning to the hills and waited anxiously for newspaper headlines announcing new atrocities. We didn’t have to wait long. It was at Holly Grove. In the dead of night, with all ligjnts extinguished, the armored train drew up over the sleeping tent colony and opened fire with rifles and machine guns. Wooden shacks were splintered and tents riddled with bullets. One woman was reported to have both legs broken by the rain of lead. A miner holding an infant in his arms, and running from his tent to shelter in a dugout, fell, seriously wounded. The baby, by some miracle was unhurt, but it was reported that three bullet holes had tattered the edge of her calico dress. Men, women, and children ran hastily through the night, seeking the cold shelter of the woods . .

Chaplin described a trip he and Elmer Rumbaugh made to collect information for an article, immediately after the Holly Grove incident. He wrote: “In every town we passed, miners were gathered in little anxious groups. Feeling was running high. I heard miners saying on every side, ‘Just wait until the leaves come out!’ This remark puzzled me until the desperate implications became apparent. The leafless hillsides made the miners targets for enemy fire and exposed their movements when they were seeking points of vantage from which to take pot shots at guards and militiamen…. At two roadway junctions we could plainly see the yellow wigwams of the militiamen, with stacked rifles glistening beside them. Several times we caught glimpses of machine guns overlooking the frail tent colonies of the miners.”

“When we were on our way back home hell broke loose in the entire Kanawha Valley. We were caught in the midst of it. Armed miners from all parts of the state were on the march with the avowed purpose of destroying the hated ‘Death Train.’ … There were hundreds of incidents … We passed through a district where, in a single engagement, sixteen men had been killed or, as the strikers put it, ‘four men and twelve gun thugs’ … We were exposed to intermittent fire for three full days before we finally caught a freight back to Charleston. I arrived in Westmoreland once more, dog-tired and black with cinders, I sat down at the kitchen table and scribbled stanzas of ‘When the Leaves Come Out.’ It had been tormenting me all the way home. It has tormented me, in a different way, many times since then, because I have found it tucked away in too many miners’ homes.”

“The Kanawha Striker,” “Mine Guard,” and “When the Leaves Come Out,” which were printed in the International Socialist Review (1914), were collected in a privately printed edition of Chaplin’s early poems, When The Leaves Come Out (Chicago, 1917). Ralph Chaplin sent the manuscripts to Miss Inglis who included them in the file on Ralph Chaplin in the Labadie Collection.

Good God! Must I now meekly bend my head

And cringe back to that gloom I know so well?

Forget the wrongs my tongue may never tell,

Forget the plea they silenced with their lead,

Forget the hillside strewn with murdered dead

Where once they drove me—mocked me when I fell

All black and bloody by their holes of hell,

While all my loved ones wept uncomforted?

Is this the land my fathers fought to own—

Here where they curse me—beaten and alone?

But God, it’s cold! My children sob and cry!

Shall I go back into the mines and wait,

And lash the conflagration of my hate—

Or shall I stand and fight them till I die?

The hills are very bare and cold and lonely;

I wonder what the future months will bring?

The strike is on—our strength would win, if only—

O, Buddy, how I’m longing for the spring!

They’ve got us down—their martial lines enfold us;

They’ve thrown us out to feel the winters sting,

And yet, by God, those curs could never hold us,

Nor could the dogs of hell do such a thing!

It isn’t just to see the hills beside me,

Grow fresh and green with every growing thing.

I only want the leaves to come and hide me,

To cover up my vengeful wandering.

I will not watch the floating clouds that hover

Above the birds that warble on the wing;

I want to use this GUN from under cover—

O, Buddy, how I’m longing for the spring!

You see them there below, the damned scab-herders!

Those puppets on the greedy Owners’ String;

We’ll make them pay for all their dirty murders—

We’ll show them how a starving hate can sting!

They riddled us with volley after volley;

We heard their speeding bullets zip and ring,

But soon we’ll make them suffer for their folly—

O, Buddy, how I’m longing for the spring!

3

You cur! How can you stand so calm and still

And careless while your brothers strive and bleed?

What hellish, cruel, crime-polluted creed

Has taught you thus to do your master’s will,

Whose guilty gold has damned your soul until

You lick his boots and fawn to do his deed—

To pander to his lust of boundless greed,

And guard him while his cohorts crush and kill?

Your brutish crimes are like a rotten flood—

The beating, raping, murdering you’ve done—

You sycophantic coward with a gun:

The worms would scorn your carcass in the mud;

A bitch would blush to hail you as a son—

You loathsome outcast, red with fresh-spilled blood!

4

Pat Brennan, author of the popular “Harvest War Song,” composed these verses which appeared in Voice of the People (September 17, 1914).

We delve in the Mines, down below, down below.

Yes, we delve in the Mines down below;

We give to the World all the wealth that we mine,

Yet we’re slaves to the mines down below;

We’re stripped to the waist like a savage of old,

Down in the regions where cold is unknown.

Our Masters have made us, for ages untold,

Their Slaves in the mines down below, down below,

Their Slaves in the mines down below.

With shovel and pick we work till we’re sick,

Down in the mines down below, down below;

Down in the mines, down below.

With hammer and drill we drive and we fill

Our lungs with the gases, the gases that kill;

We’re sent to the “Flats,” all rigid and still,

Us Slaves from the mines down below, down below,

Us Slaves from the mines down below.

But let’s stand together for once at the top,

Then you bet your sweet life the murders will stop—

And don’t go to work till you’ve had your own way,

Down in the mines down below, down below,

Down in the mines, down below.

5

This unsigned song appeared in Solidarity (August 5,1916) during the strike of the iron ore miners on the Mesabi Range in Minnesota.

Solidarity, September 16, 1916.

(Written in Jail)

(Tune: “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”)

The Miners of the Iron Range

Know there was something wrong

They banded all together, yes,

In One Big Union strong.

The Steel Trust got the shivers,

And the Mine Guards had some fits,

The Miners didn’t give a damn,

But closed down all the pits.

Chorus—

It’s a long way to monthly pay day,

It’s a long way to go

It’s a long way to monthly pay day,

For the Miners need the dough,

Goodbye Steel Trust profits,

The Morgans they feel blue.

It’s a long way to monthly pay day

For the miners want two.

They worked like hell on contract, yes,

And got paid by the day,

Whenever they got fired, yes,

The bosses held their pay.

But now they want a guarantee

Of just three bones a day,

And when they quit their lousy jobs

They must receive their pay.

Chorus—

It’s the wrong way to work, by contract

It’s the wrong way to go.

It’s the wrong way to work by contract

For the Miners need the dough.

Goodbye bosses’ handouts,—

Farewell Hibbing Square.

It’s the wrong way to work by contract

You will find no Miners there.

John Allar died of Mine Guards’ guns

The Steel Trust had engaged.

At Gilbert, wives and children

Of the Miners were outraged

No Mine Guards were arrested,

Yet the law is claimed to be

The mightiest conception

Of a big democracy.

Chorus—

It’s the wrong way to treat the Miners,

It’s the wrong way to go.

It’s the wrong way to best the Miners,

As the Steel Trust soon will know.

God help those dirty Mine Guards,

The Miners won’t forget.

It’s the wrong way to treat the Miners,

And the guards will know that yet.

The Governor got his orders for

To try and break the strike.

He sent his henchmen on the Range,

Just what the Steel Trust liked.

The Miners were arrested, yes,

And thrown into the jail,

But yet they had no legal rights

When they presented bail.

It is this way in Minnesota

Is it this way you go?

It is this way in Minnesota,

Where justice has no show.

Wake up all Wage Workers,

In One Big Union strong.

If we all act unified together,

We can right all things that’s wrong.

Chorus—

It’s a short way to next election,

It’s a short way to go.

For the Governor’s in deep reflection

As to Labor’s vote, you know.

Goodbye, Dear Old State House,

Farewell, Bernquist there.

It’s a short way to next election

And you’ll find no Bernquist there.

Get busy, was the order to

The lackeys of the Trust,

Jail all the Organizers

And the Strike will surely bust.

Trump up a charge, a strong one,

That will kill all sympathy,

So murder was the frame-up,

And one of first degree.

Chorus—

It is this way in Minnesota

Is it this way you go?

It is this way in Minnesota,

Wake up all Wage Workers,

In One Big Union strong.

If we all act unified together,

We can right all things that’s wrong.

6

The following five songs were included in an undated, paperbound collection of twenty-five poems and songs, titled New Songs for Butte Mining Camp. Acquired by I.W.W. member John Neu-house and now in the library of folklorist Archie Green, this booklet has been microfilmed by the Stanford University Library. A copy of the microfilm is in the Labadie Collection.

Page Stegner, in an unpublished study, “Protest Songs from the Butte Mines,” wrote: “It may safely be said that few if any of the songs in this book have ever been reprinted, and there is considerable doubt whether they were widely known in Butte even at the time they were written. Apparently, they never entered oral tradition, the principal scholars in the field have not noted their existence, and they are not remembered by anyone yet interviewed who lived and worked in Butte. In any scholarly definition they cannot be considered folksongs, yet this does not eliminate their importance to the folklorist or the labor historian. Their real value lies in the insights they give into the actual causes of the strikes and labor problems from the viewpoint of the miner and labor organizer. Furthermore, they are representative not only of the causes of labor agitation, but also of what the labor organizers thought would be the most stirring issues among Butte workmen and most useful for organizing the labor class. They are social documents of this class in the Butte mining area.”

Tom Campbell, who is mentioned in these poems, was the Butte miners’ leader who ran against Charles Moyer for the presidency of the Western Federation of Miners in 1912, charging that W.F.M. officials had done nothing to oppose the newly instituted “rustling card” system in Butte nor the discharge of a large number of Finnish Socialist miners. Campbell was expelled from the W.F.M. for these charges. In 1917 he was elected president of a new union, the Metal Mine Workers, formed after the June 1917 Speculator Mine fire of the North Butte Mining Company.

“Con” Kelly was Cornelius Kelly, vice-president of the Anaconda Copper Company, the largest ore producer in Butte. Kelly is reported to have said that he would see the grass grow on the muck heaps in Butte before meeting the demands for better working conditions presented to the company by the I.W.W. This remark is preserved in Scottie’s song, “Cornelius Kelly.”

Page Stegner noted: “Perhaps one of the most important contributions of the song book to labor history and the labor historian is the way in which several of the songs reflect the difficulties labor organizers had in breaking down ethnic barriers and getting workers to cooperate with other racial groups. Scottie’s song, ‘Workers Unite,’ is one of the best examples of this problem.”

Both Scottie and Joe Kennedy were remembered by a retired electrician, Tiger Thompson, a Wobbly who worked in the mines of Butte in 1917 and 1918, who was interviewed by Stegner in Portola Valley, California.

(Tune: “Standard on the Braes O May”)

The miners in the mines of Butte

Are in rebellion fairly,

The gathering clouds of discontent

Are spreading fast and surely.

The miner’s life is full of strife,

In stopes and drifts and raises,—

Don’t judge him hard, give him his due,

He needs our loudest praises.

Down in these holes each shift he goes

And works mid dangers many,

And gets the “miner’s con” to boot,

The worst disease of any;

In hot-boxes he drills his rounds,

Midst floods of perspiration,

And clogs his lungs with copper dust,—

A hellish occupation.

The merry breezes never blow

Down in these awful places

The sun’s rays are one-candle power

That shines on pallid faces;

The only birds that warble there

Are “buzzies” and “jack hammers,”

Their song is death in every note,

For human life they clamour.

Conditions such as these, my friends,

Have made the miners rebels,

The under-current is gaining strength,

The mighty system trembles;

The revolution’s coming fast,

Old institutions vanish,

The tyrant-rule from off the earth

For evermore ‘twill banish.

7

(Tune: “The Campbells Are Coming”)

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

The “Campbell’s real union” is here to stay

The buttons are blazing, the bosses are raving

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

The Englishman, Scotchman and Irishman, too,

American, Dutchman, Finlander and Jew,

Solidarity, July 7, 1917.

Are all turning Campbells, good luck to the day,

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

The rustling card system, it sure has to go,

Six dollars we ask and more safety below,

And after awhile six hours in the day

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

The prostitute-press is bucking us hard,

And the A. F. of L. is just quite as bad,

But well show them all we’re made of right clay,

The Campbells have come and they’re going to stay.

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

The “real Campbell’s union” is here to stay,

The buttons are blazing, the bosses are raving,

The Campbells are coming, Hooray! Hooray!

Solidarity, July 14, 1917.

8

Of all the men in old Butte City,

That needs contempt or even pity,

There’s one that rules on the Sixth Floor

That’s got them all skinned, by the score.

This old gent’s name is Cornelius Kelly,

Was meant to crawl upon his belly,

But listen, boys, he’s good and true

The Company’s interests to pull thru,

But when it comes to working men,

He’d rather see them in the pen,

Or burning in eternal hell,—

His nostrils would enjoy the smell.

“The grass would grow,” so says this plute,

“In Anaconda and in Butte,

Before I meet the men’s demands,

As this is final as it stands.”

All right, old boy, the time will tell,

You cannot stop the ocean’s swell;

It’s we who dig the copper ore,

While you lie in your bed and snore;

It’s we who fold our arms and stand

Until we get our just demand.

Five months ago we told you so—

(The grass is coming very slow).

9

On the twelfth of June we called a strike

Which filled the miners with delight,

In union strong we did unite,

On the rustling card to make a fight.

The Bisbee miners fell in line,

And believe me, Miami was not far behind;

In Globe they surely were on time,

To join their striking brothers.

The companies were money mad,

This strike made dividends look sad;

The men to Con these words did say,

“They’ll be twice as short before next May.”

The local press it came out bold

And said it must be German gold,

Although we did not have a dime

The morn we hit the firing line.

Although we re classed as an outlaw band,

We’ve surely made a noble stand,

Our fight is just for liberty

And make Butte safe for democracy.

Six hundred gunmen came to town

And tried to keep the strikers down,

In spite of all we re full of vim,

Our password is, “we re bound to win!”

The old war-horse is in the game

I know all rebels heard his name,

For thirty years and more, I’m told,

His fellow-workers never sold.

The A.C.M. they tried their skill,

When Fellow-Worker Little’s blood did spill,

The day will come when union men

Will have a voice in Butte again.

Fellow-Worker Campbell, true and bold,

His comrades would not sell for gold;

He said to Con, “Why, 111 get mine

By standing on the firing line.”

Now respect to all true union men,

Who have courage to fight until the end;

To copper barons we will say,

“The rustling card has gone to stay.”

10

Ye sons that come from Erin s shore,

Just list to what I’ve got in store,

Of Celtic race and blood you came,

Of fighting blood and noble strain.

Your blood on every battle field,

You’ve shed for master class to wield,

The Iron Hand in name of state,

To bring you to an awful fate.

But, Irishmen, you’re not to blame,

In other lands it’s just the same,

The workers of the world are slaves,

The parasites are heartless knaves.

If you’d be free, you’ve got to stand,

With working men from every land;

Race prejudice you’ve got to banish

From out your minds and not be clannish.

Our interests are just the same

From County Cork to State of Maine,

The master rules with iron hand,

From Australia to Baffin’s Land.

So Workers of the World unite

Beneath one banner for the right,

In Labor’s ranks there is a place

For every man of every race.

Now, Erin’s sons, again I say,

Don’t be a slacker in the fray;

The world for workers be your cry,

Resound aloud from earth to sky.

Frank Little.

Labadie Collection photo files.

Like Bill Haywood, Frank Little had only one good eye. He boasted of being half Indian. He was one of the most courageous and dynamic of the I.W.W. organizers. Chairman of the I.W.W. General Executive Board, Little had been active in the I.W.W. since 1go6. He had helped lead the Missoula, Spokane, and Fresno free speech fights, and had organized lumberjacks, metal miners, oil workers, and harvest stiffs into the One Big Union. With one leg in a plaster cast from an accident he had while organizing in Oklahoma, Frank Little arrived in Butte, Montana, shortly after the Speculator Mine fire, when infuriated Butte miners refused to go back to work until their demands were met for improved safety conditions and an end to long-standing grievances. Following a speech at the ball park in Butte on July 31, 1917, Little went to his room at the Finn Hotel. That night, six masked and armed men broke into his room, beat him, and dragged him by a rope behind their automobile to a Milwaukee Railroad trestle on the outskirts of Butte. There he was hung. On his coat was pinned a card: “First and last warning! 3-7-77. D-D-C-S-S-W.” It was said that the numbers referred to the measurements of a grave and that the initials corresponded to the first letters of the names of other strike leaders in Butte, thereby warning them of similar treatment if their strike activities were not stopped. No attempt was made to find Little’s assailants.

The poem, “To Frank Little,” by Viola Gilbert Snell appeared in Solidarity (August 25, 1917). “When the Cock Crows” by Arturo Giovannitti appeared in Solidarity (September 22, 1917).

The plains you loved lie parching in the sun,

The streets you tramped are sweltering in the heat,

The fertile fields are arid with the drouth,

The forests thick with smoldering fires and smoke.

Traitor and demagogue,

Wanton breeder of discontent-

That is what they call you—

Those cowards, who condemn sabotage

But hide themselves

Not only behind masks and cloaks

But behind all the armored positions

Of property and prejudice and the law.

Staunch friend and comrade,

Soldier of solidarity—

Like some bitter magic

The tale of your tragic death

Has spread throughout the land,

And from a thousand minds

Has torn the last shreds of doubt

Concerning Might and Right.

Young and virile and strong-

Like grim sentinels they stand

Awaiting each opportunity

To break another

Of slavery’s chains.

For WHATEVER stroke is needed.

They are preparing.

So shall you be avenged.

Within our hearts is smoldering a heat

Fiercer than that which parches fields and plains;

Your memory, like a torch, shall light the flames

Of Revolution. We shall not forget.

12

To the Memory of Frank Little Hanged at Midnight

I

Six MEN drove up to his house at midnight, and woke the poor woman who kept it,

And asked her: “Where is the man who spoke against war and insulted the army?”

And the old woman took fear of the men and the hour, and showed them the room where he slept,

And when they made sure it was he whom they wanted, they dragged him out of his bed with blows, tho’ he was willing to walk,

And they fastened his hands on his back, and they drove him across the black night,

And there was no moon and no star and not any visible thing, and even the faces of the men were eaten with the leprosy of the dark, for they were masked with black shame,

And nothing showed in the gloom save the glow of his eyes and the flame of his soul that scorched the face of Death.

NO ONE gave witness of what they did to him, after they took him away, until a dog barked at his corpse.

But I know, for I have seen masked men with the rope, and the eyeless things that howl against the sun, and I have ridden beside the hangman at midnight.

They kicked him, they cursed him, they pushed him, they spat on his cheeks and his brow,

They stabbed his ears with foul oaths, they smeared his clean face with the pus of their ulcerous words,

And nobody saw or heard them. But I call you to witness, John Brown, I call you to witness, you Molly Maguires,

And you, Albert Parsons, George Engle, Adolph Fischer, August Spies,

And you, Leo Frank, kinsman of Jesus, and you, Joe Hill, twice my germane in the rage of the song and the fray,

And all of you, sun-dark brothers, and all of you harriers of torpid faiths, hasteners of the great day, propitiators of the holy deed,

I call you all to the bar of the dawn to give witness if this is not what they do in America when they wake up men at midnight to hang them until they’re dead.

III

UNDER a railroad trestle, under the heart-rib of progress, they circled his neck with the noose, but never a word he spoke.

Never a word he uttered, and they grew weak from his silence,

For the terror of death is strongest upon the men with the rope,

When he who must hang breathes neither a prayer nor a curse,

Nor speaks any word, nor looks around, nor does anything save to chew his bit of tobacco and yawn with unsated sleep.

They grew afraid of the hidden moon and the stars, they grew afraid of the wind that held its breath, and of the living things that never stirred in their sleep,

And they gurgled a bargain to him from under their masks.

I know what they promised to him, for I have heard thrice the bargains that hounds yelp to the trapped lion:

They asked him to promise that he would turn back from his road, that he would eat carrion as they, that he would lap the leash for the sake of the offals, as they—and thus he would save his life.

But not one lone word he answered—he only chewed his bit of tobacco in silent contempt.

IV

NOW BLACK as their faces became whatever had been white inside of the six men, even to their mothers’ milk,

And they inflicted on him the final shame, and ordered that he should kiss the flag.

They always make bounden men kiss the flag in America where men never kiss men, not even when they march forth to die.

But tho’ to him all flags are holy that men fight for and death hallows,

He did not kiss it—I swear it by the one that shall wrap my body.

He did not kiss it, and they trampled upon him in their frenzy that had no retreat save the rope,

And to him who was ready to die for a light he would never see shine, they said, “You are a coward.”

To him who would not barter a meaningless word for his life, they said, “You are a traitor.”

And they drew the noose round his neck, and they pulled him up to the trestle, and they watched him until he was dead,

Six masked men whose faces were eaten with the cancer of the dark, One for each steeple of thy temple, O Labor.

V

NOW HE is dead, but now that he is dead is the door of your dungeon faster, O money changers and scribes, and priests and masters of slaves?

Are men now readier to die for you without asking the wherefore of the slaughter?

Shall now the pent-up spirit no longer connive with the sun against your midnight?

And are we now all reconciled to your rule, and are you safer and we humbler, and is the night eternal and the day forever blotted out of the skies,

And all blind yesterdays risen, and all tomorrows entombed,

Because of six faceless men and ten feet of rope and one corpse dangling unseen in the blackness under a railroad trestle?

No, I say, No. It swings like a terrible pendulum that shall soon ring out a mad tocsin and call the red cock to the crowing.

No, I say, No, for someone will bear witness of this to the dawn,

Someone will stand straight and fearless tomorrow between the armed hosts of your slaves, and shout to them the challenge of that silence you could not break.

VI

“BROTHERS—he will shout to them—”are you, then, the God-born reduced to a mute of dogs

That you will rush to the hunt of your kin at the blowing of a horn?

Brothers, have then the centuries that created new suns in the heavens, gouged out the eyes of your soul,

That you should wallow in your blood like swine,

That you should squirm like rats in a carrion,

That you, who astonished the eagles, should beat blindly about the night of murder like bats?

Are you, Brothers, who were meant to scale the stars, to crouch forever before a footstool,

And listen forever to one word of shame and subjection,

And leave the plough in the furrow, the trowel on the wall, the hammer on the anvil and the heart of the race on the knees of screaming women, and the future of the race in the hands of babbling children,

And yoke on your shoulders the halter of hatred and fury,

And dash head-down against the bastions of folly,

Because a colored cloth waves in the air, because a drum beats in the street,

Because six men have promised you a piece of ribbon on your coat, a carved tablet on a wall and your name in a list bordered with black?

Shall you, then, be forever the stewards of death, when life waits for you like a bride?

Ah no, Brothers, not for this did our mothers shriek with pain and delight when we tore their flanks with our first cry;

Not for this were we given command of the beasts,

Not with blood but with sweat were we bidden to achieve our salvation.

Behold: I announce now to you a great tidings of

For if your hands that are gathered in sheaves for the sickle of war unite as a bouquet of flowers between the warm breasts of peace,

Freedom will come without any blows save the hammers on the chains of your wrists, and the picks on the walls of your jails!

Arise, and against every hand jeweled with the rubies of murder,

Against every mouth that sneers at the tears of mercy,

Against every foul smell of the earth,

Against every hand that a footstool raised over your head,

Against every word that was written before this was said,

Against every happiness that never knew sorrow,

And every glory that never knew love and sweat,

Against silence and death, and fear,

Arise with a mighty roar!

Arise and declare your war:

For the wind of the dawn is blowing,

For the eyes of the East are glowing,

For the lark is up and the cock is crowing,

And the day of judgment is here!”

VII

THUS shall he speak to the great parliament of the dawn, the witness of this murderous midnight,

And even if none listens to him, I shall be there and acclaim,

And even if they tear him to shreds, I shall be there to confess him before your guns and your gallows, O Monsters!

And even tho’ you smite me with your bludgeon upon my head,

And curse me and call me foul names, and spit on my face and on my bare hands,

I swear that when the cock crows I shall not deny him.

And even if the power of your lie be so strong that my own mother curse me as a traitor with her hands clutched over her old breasts,

And my daughters with the almighty names, turn their faces from me and call me coward,

And the One whose love for me is a battleflag in the storm, scream for the shame of me and adjure my name,

I swear that when the cock crows I shall not deny him.

And if you chain me and drag me before the Beast that guards the seals of your power, and the caitiff that conspires against the daylight demand my death,

And your hangman throw a black cowl over my head and tie a noose around my neck,

And the black ghoul that pastures on the graves of the saints dig its snout into my soul and howl the terrors of the everlasting beyond in my ears,

Even then, when the cock crows, I swear I shall not deny him.

And if you spring the trap under my feet and hurl me into the gloom, and in the revelation of that instant eternal a voice shriek madly to me

That the rope is forever unbreakable,

That the dawn is never to blaze,

That the night is forever invincible,

Even then, even then, O Monsters, I shall not deny him.

13

This unsigned poem appeared in the One Big Union Monthly (August 1919).It is the only piece of writing found thus far to commemorate the events of July 12, 1917, in Bisbee, Arizona, when an armed vigilante committee raided the homes of striking miners, loaded over 1160 of them into cattle cars, and deported them to the town in the desert where they were retained until September, following the end of their strike.

By Card No. 512210

We are waiting, brother, waiting

Tho the night be dark and long

And we know ‘tis in the making

Wondrous day of vanished wrongs.

They have herded us like cattle

Torn us from our homes and wives.

Yes, we’ve heard their rifles rattle

And have feared for our lives.

We have seen the workers, thousands,

Marched like bandits, down the street

Corporation gunmen round them

Yes, we’ve heard their tramping feet.

It was in the morning early

Of that fatal July 12th

And the year nineteen seventeen

This took place of which I tell.

Servants of the damned bourgeois

With white bands upon their arms

Drove and dragged us out with curses

Threats, to kill on every hand.

Question, protest all were useless

To those hounds of hell let loose.

Nothing but an armed resistance

Would avail with these brutes.

There they held us, long lines weary waiting

‘Neath the blazing desert sun.

Some with eyes bloodshot and bleary

Wished for water, but had none.

Yes, some brave wives brought us water

Loving hearts and hands were theirs.

But the gunmen, cursing often,

Poured it out upon the sands.

Down the streets in squads of fifty

We were marched, and some were chained,

Down to where the shining rails

Stretched across the sandy plains.

Then in haste with kicks and curses

We were herded into cars

And it seemed our lungs were bursting

With the odor of the Yards.

Floors were inches deep in refuse

Left there from the Western herds.

Good enough for miners. Damn them.

May they soon be food for birds.

No farewells were then allowed us

Wives and babes were left behind,

Tho I saw their arms around us

As I closed my eyes and wept.

After what seemed weeks of torture

We were at our journey’s end.

Left to starve upon the border

Almost on Carranza’s land.

Then they rant of law and order,

Love of God, and fellow man,

Rave of freedom o’er the border

Being sent from promised lands.

Comes the day, ah! we’ll remember

Sure as death relentless, too,

Grim-lipped toilers, their accusers,

Let them call on God, not on you.

This “Tightline Johnson” story by Ralph Winstead finds the Wobbly Johnson in a coal mining camp. It appeared in the Industrial Pioneer (January 1922).

Education accordin’ to my idea is a matter of grabbin’ onto and arrangin in the mind all sorts of new ideas and experiences. When a fellow just grabs onto ideas and never has any experiences, why, about all he is good for is to spread ideas. When it comes to action the idea guy is handin’ out the absent treatment.

Coal minin’ is not generally listed as one of the essentials to a finished education, but it is sure a form of experience that is liable to change one’s ideas. My first mingling with the black diamonds happened after I had put in about seven months on the shelf with a busted leg. The Doc, in his last once over, had told me that all I needed was light exercise and change, and so I started out to find the change, intendin’, of course, to take my exercise as lightly as possible.

After ramblin’ around for a few crispy fall days and nights I landed without malice or forethought in a coal camp out of Tacoma some considerable ways. The two strings of whitewashed miners’ shacks strung along a narrow canyon with the railroad, wagon road, promenade and kids’ playground occupyin’ the fifty feet of space between the rows of workingmen’s places completed the residence section.

The mine buildings mostly lay up on the side hill and looked like the dingiest collection of hangman’s scaffolds that ever happened. There is some things that all the doctorin’ and fussin’ in the world ain’t goin’ to make restful to sore eyes, and a coal mine is one of ’em. Everything, from the bunker chutes up to the hoist house, is usually covered with the dust of dirty years and the buildings are, as the British remittance man says of his squaw wife, “Built for use and not for display.”

When I first ventured on the scene the night shift was just gatherin’ toward the biggest scaffold of the whole bunch, so I wandered over that way myself. The big tower supported two bull wheels that ran in opposite directions, guiding cables which were pulling a trip of loaded coal cars up on one track while the other cable was sending down the empties on the other track.

The hole in the ground, into which these cables ran from the bull wheel, went straight in for about fifty feet and then seemed to jump off. Electric lights made the inside bright as day so that the well of inky blackness beyond the lights showed up strong. The cables roared and the ground shook to the rapid explosion of the steam hoist. This, I surmised, was a place for a cool head and a steady hand.

While I was watchin’, a coal smeared lad about of a size to be studyin’ fractions moseyed out to the jumpin’ off place. The roar of the cables increased, then was drowned in a growin’ mightier noise. The lad crouched as for a spring. The mighty roar achieved a climax. A hurtling black shape come pushing over the brink. The boy leaped in the air and landed square on the end of the moving mass.

He stooped, grasped the couplin’ that fastened the hoistin’ cable to the end of the car and, jerkin’ it loose, threw clevis and gear clear of the track. He leaped to the ground and gave scarcely a glance at the swift movin’ train of loaded one ton cars which went chargin’ through a muddle of switches out onto a trestle, where another and smaller boy took them in charge.

I was all excited by these maneuvers. I felt just like the time when the high climber accidentally cut his life rope with the axe and climbed down hangin’ onto the bark of the spare tree with his hands. Nobody else seemed to be much excited and the kid that had gone through the performance least of all. He hustled some empties into the tunnel, hooked ’em up and fastened the cable on and soon another trip was hurryin’ up from the guts of the earth while the empties were goin down.

On all sides there was a bunch of little shavers scurrym around amongst the cars spraggin’, oilin’, shovin’ and pushin’. There was a whole raft of ’em. Kids and coal minin’ seem to work together. I grew a lot of respect for coal miners in a few minutes. “If the kids were set at this sort of a job,” thinks I, “what was expected of the men?” I turned and sized up the group that was hangin’ round.

I saw right away where I was goin’ to horn in on some light exercise, for each one of these grimy slow movin’ plugs was exercisin’ some sort of a light. Some wore ’em on their caps like a posie on a summer bonnet, while another sort was carried in the hand like a little lantern.

I felt a big desire to have a shining light hung on me, so I approached one of the nearest light bearers and probed him as to how to get a job in the outfit.

Did you ever notice the hostility of some slaves toward the strangers that are rustlin’ a job from their masters? Well, this strange-cow-in-the-pas-ture attitude was noticeable for its absence here. I got all the information wanted cheerfully, and then went over and tackled the shifter, who looked just like the rest of the gang except that he carried two lights and a little more dry black mud.

He seemed almost human. Instead of askin’ about my lurid past or family connections, he seemed interested in the jobs to be filled and my ability to fill ’em. He went into the lamp house to see how the gang was lined up and came out with the haulage boss, who sized me up and said a few words about trips and number seven motor while I looked wise. I hooked a job ridin’ trip and was told to report the next day for afternoon shift.

After enterin’ my name and number in the office I went down to look for the boardin’ house. This affair was in one of the bigger white-washed shacks and the boardin boss was a big fat woman with a cockney accent and a warm and generous smile.

Accommodations was not exactly luxurious. I got a little single cot in a room with two other fellows. I was informed that the union had a big bath house by the mine so that all washin’ up would be done there.

While I was sittin’ in the main room on one of the luxurious kitchen chairs, the missus came in for a chat. She asked me about my clothes and finances as if she was an old pal. Finding that I was goin’ to work on the haulage crew she told me right off that I would need a miner’s cap and some shoe grease. Then she wrote out a slip that made my face good at the company store and I went up to this institution and got the goods.

The company store is a sort of clearing house. The bookkeeper is the postmaster, the timekeeper and paymaster all rolled into one by hand. He was a busy plug. A miner would put in so much time in the mine and would be given credit on the books for so much. His store bill, union dues and doctor’s fees were deducted from his credit balance and what was over he could get in cash every two weeks or so.

What struck me most was the spirit of friendliness that everyone showed. There was little of the backbitin’ and hate that is found in so many small towns and camps. A tolerant spirit was floatin’ around in the air and one seemed to grab onto it right away. Yet it was a rough and critical tolerance and not of the smooth, oily sort that one finds among the so-called cultured people.

I mentioned the fact to the boardin’ missus. She told me that there was jealousies and hates all right, but the general ideas of the miners discouraged ’em. She rattled off a few phrases like solidarity and direct action and the like, tryin’ to describe the past battles and conditions and I sat up and took notice. The boardin’ missus was no slouch to my mind. She explained how conditions were fought for.

Durin’ the evenin’ I had a good time listenin’ to the rag chewin’ that was carried on in the sittin’ room and out on the porch. Some of the boys had good ideas and I sat there as pleased as a bald headed man in the front row.

Next afternoon at three o’clock I reached the pit mouth and after gettin’ my lamp and brass check number I hung around with the rest of the bunch and watched the top eager go through his gymnastics with the gallopin’ cars. One of the miners came over and told me in a friendly way that I should be sure not to take any matches down with me, as that would raise hell if I did. I searched every pocket and got rid of all that I had. Later on I found that this gentle-voiced old Finn was chairman of the safety committee.

They rolled out the man cars. They was queer lookin’ rigs, just big open topless boxes on wheels with boards for seats, nailed crossways and slanting up in the air at an angle like the cow guards on a railroad crossing. When the car was runnin’ down the slope the seats was about horizontal.

As one car went down with a load of night shift men the other car came up from the bottom with a load of the day shift. The plugs comin’ off sure didn’t impress one with bein’ specimens of manly beauty. Smeared with coal dust and mud, with their clothes sticky and black with scrapins from chute and wall they was sure a hard lookin’ bunch.

Finally I got into the car with a big Italian that had taken me under his wing. We moved out slowly to the jump off and then picked up speed goin’ down the steep slope.

Everything was dark except for the light in our caps and these made the timbers that capped the slope and the posts and walls on the sides, quite plain. Half way down we passed the other car comin up. All that we could see was a blur of lights as they whizzed by.

Solidarity, August 11, 1917.

In order to make me feel good Tony alongside told about mines where the cable had broken while they were pullin’ the men out. He told about the runaways with such happy satisfaction that I figured that he was kiddin’ me. Later I found that he was only happy because it was the truth. You know a fellow always gets a sort of kick out of doin’ dangerous things cheerfully. The coal owners sure used short sightedness when they plastered the pit buildings full of safety first posters with the old bunk that it never pays to take a chance. If the miners really acted on that idea there would be a lot of perfectly good machinery and coal burnin stoves bein lugged up to the pawn shop, right away. Coal would be an inter-estin’ specimen.

At last we rolled out on the bottom of the eighteen hundred foot slope and we scrambled out on one side of the car while a gang of fierce eyed, muddy and sweaty miners piled in on the other side. There was no confusion however as the first men down were the first ones up and there was strict enforcement of the rule. The car climbed up and disappeared and I looked around me at this electric lighted gallery so deep under ground. The first thing that took my eyes was some petrified clam shells on the hangin wall just as natural as if they were ready to furnish the makins of a Coney Island chowder. Many a thing had happened in this highly important world of ours since they had played their last squirt in the sunshine on the beach.

We checked in, to a man with a book, and a big pencil, who kept track of the trip loads comin’ down and goin up. As I was walking on past groups of miners waitin’ their turn to go up, a little hard lookin Scot jumped out at me with a pad and pencil.

“Hi Laddie—sign this paper!” he commanded.

“What is it?” I asked thinkin’ maybe it was a contribution list for indignant Armenians or some-thin’ like it.

“It’s the union check off, Laddie,” he said seriously, “and you’ll have to sign it if you work wi’ us.” So I signed up and was a miners’ union man, except for the sacred oath with the right hand on the left breast in front of the Imperial Lizard.

Then I came to a little Italian who was the haulage boss on my shift. He was an excitable high ball artist but was ashamed of it and tried to cover it up with a forced good nature. He kept his mind fixed on the tonnage at all times. Otherwise he seemed a hell of a fine fellow. He had a hard case of producers’ mental cramp.

This boss took me over to a squat fat Austrian who was tinkerin’ with a low, wicked lookin’ motor, that looked like an armored car more than anything else. They told me to sit down and wait till the rest of the trips had pulled in to the different veins and chutes to load up and then we would start.

The night shift trooped by to their places in the interior and trip by trip the crowd of men on the bottom lessened. When the watch said four o’clock the trips commenced to roll out of the bottom with their ten and fifteen cars into the dark narrowness of the miles of tunneled gangways each foot of which had its danger to the trip rider and haulage man.

At last we too hooked onto a string of cars and went rolling into the mysterious inside. The big blue sparks from the trolley snapped and flamed while faster and faster the trip moved into the darkness with Johnny the boss, and myself draped over the end of the last car.

In places the roof was low and timbers had to be dodged or they would brush a plug off like he was a fly. Then the trolley hung low and there was a constant danger of touchin’ it and gettin’ electrocuted about half way.

A thousand dangers was on every hand. The little light on my cap was all that enabled me to see the overhead things that was ready to cave in my dome at any time I grew careless.

Johnny explained that I would get to know these dangers and would safeguard myself without thinkin’ about it. “It’s like a guy walkin’,” he said. “He’s takin’ a chance every minute dat he might fall down and bust his neck but he gets so used to it dat he protects himself widout any worryin’ at all. Besides dis is nuttin’. You’d ought to see what de miners is up against, up de pitch.”

We turned off of one tunnel into another and passed yawning black gangways to right and left but kept on goin’. These miles of track down here that took so many hours and days of workin’ together to build, these thousands of timbers each set of which took plannin’ and figurin’ of whole gangs workin’ for one impersonal end, the dozens of miles of galleries, gangways, chutes, counter air courses, and escapeways, all of these played up by the flickin’ light of my head lamp and emphasized by the pitchy blackness that was only relieved by the station lamps shinin so far away, these things sure made a guy feel like he was only a small part of somethin’ and not the whole cheese.

Mines I decided was no place for individual freedom. The more I saw of my job that day the more I figured that this was correct. We loaded trip after trip of cars full to overflowing, from the chutes. The miners up the pitch depended on us to use our heads at all times so that they would not be cut off in the black damp and gas that was sure to gather when the air courses were diverted.

Every thing you did had to be done just so, on account, of the peculiar desire that a lot of the rest of us have, to remain all in one piece that can move around some. And that is what coal mining amounts to. It is a wild struggle to get the wages that can be had by diggin’ coal, diggin’ the coal and stayin’ in such a shape so that the wife will recognize you when you come home. This complication naturally needs unionism and real helpful understanding of the local problems.

Unionism is my long suit and you can bet I was interested in the one that I had just joined. A lot of us has heard about the United Mine Workers and the funny thing is that the news is mostly in two classes, that is the sort of news that we can rely on. One sort of material is like the facts of the Ludlow Massacre and the West Virginia battles of the last twenty years.

Then there is the other sort. The facts that Mitchell, one time official of the Mine Workers, died with an estate of hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the way that the officials often have of letting the rank and file carry on the battles of the organization when they get in a tight place while they sit back and issue public interviews discouraging the members.

Naturally I was interested in the whys and wherefores of such an organization and you can bet I was on hand to take in anything that had a bearin’ on the subject.

At the very next union meeting I got my first earful. After bein solemnly swore in I took a seat and looked at the maze of faces that looked out from the seats arranged, like the Russian bond holders, with the backs to the wall.

There was a safety committee report to listen to and I heard myself bein issued instructions from the body assembled not to leave any ties or rails layin’ alongside the track in the gangways and was impressed with the need to handle things with an eye to the welfare of my fellow workers. These fellows was lookin’ after the bosses’ business in order to keep out of the little plot of holy-ground up on the hill.

Then they discussed methods of pullin’ pillars and seemed to take exception to the technique of one of the bosses in this respect. The said boss was called in and made his statement in regards to the matter and was issued instructions to pull his pillars in the way that provided some chance of escape in at least nine out of ten times if you’re lucky.