The darkness of this northern place was lit on warm days with falling snow and on bitter days with rising columns of white exhaust that froze in the air. There were coloured lights wrapped around posts and buildings. I felt lonely watching the other students going home at Christmas after their first term away. Everywhere were decorations, red Santas and deer who pulled an imaginary sleigh. One with a bright red nose was beloved by the children. What a strange and frightening idea, a big fat man climbing into your house through the long, dirty chimney, but here the children liked it. People carried full, live trees into their houses. This I had read about with the nuns when we studied British writers. One evening after work Monique and I bought the tiniest tree we could find and we took it back to my room and leaned it against a wall and she pulled shining silver streamers she called tinsel from her pocket and decorated it and said, Voila! Your first Christmas tree! She gave me a red hat to wear and said, See if you can find a sari to match it when you play. People drink a lot at Christmas. You’ll make lots of tips. Do you know any carols?

The shopping places and the churches were visited more than usual and people were having parties with cheeses and toasts and many sweets, like holidays everywhere.

I felt foreign and I remembered Abbu and the Beach Luxury at Christmas, and the music he taught me about kings and babies. I had especially liked one about a poor boy who was a drummer. I thought too of Mor and Eid in her village, holding her mother’s hand and watching the blood of the dying goat on the ground and the new clothes she bought for me on the holiday. When she wanted to know why they made the sacrifice in front of everyone in the middle of the village, her mother squeezed her hand hard and said, Sh!

But why here?

Her mother whispered in Pashto, Be quiet! Your great-grandfather slew his newborn daughter on this spot because he did not want a female heir. This is why all ritual slaughter in the village is here.

I bought my bus ticket to New York City so I too had somewhere to go and because I had always wanted to hear American jazz.

I walked from Times Square to the Village Gate on Bleecker Street. Everyone performed there, Earl Hines and Nina Simone and Bill Evans. The place was empty but I went upstairs anyway. A man with a beard and glasses was talking to some people who were pushing tables around. He said, We’re closed.

Are you Art D’Lugoff?

The same.

Could I play here?

He took a better look at me, my backpack. He gestured to the piano and I sat down, breathed, played. I started to pump it out. I had to get Art’s attention.

How long you in town for?

A couple of weeks.

Got an agent?

I shrugged.

That was how I got my first gig in New York. He let me play warm-up for Larry Coryell for three nights. Later he told me he tried me because I surprised him. A lot of things happened in those days because of chance. People gave each other breaks. The atmosphere was very free. Everyone was playing each other’s music and I did too. Abbu used to say, Porcupine, the best musicians always steal from people who play better.

I had asked him, Did you write “Kansas City”?

He said, I don’t write. I got that song from Little Willie Littlefield. You could play it. That would be great, wouldn’t it? A half-Afghan, half-American Karachi girl who likes jazz and pahada playing “Kansas City” like she owns it. Isn’t that a world to live in, Porcupine? You play it.

*

The first set at the Gate I wore my sari like I did at Rockhead’s but it felt wrong. Everyone was talking and clinking their glasses and I don’t think one single person listened and I couldn’t get their attention. Art came by at the end and said, Fantastic! Some lies are like ointment, meant for healing. I guess he’d seen lots of people bomb. I had to make myself stay. I went into the bathroom and changed into my jeans, listened to Coryell, and later I went downstairs to hear Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers.

That was the night I met Katherine.

She wore a black hat and she had huge hands like a man and she was tall. When she sat at the piano she looked like a question mark. She had a thing with the drums and perfect rhythm, and listening to her playing with the Messengers gave me ideas. I needed to stop hiding behind my gimmicky girl-from-Pakistan routine. I went up to her when the band took a break and I told her I liked her playing and that I was playing upstairs for a couple of nights.

I said, I heard a recording of you playing in the Mo Billson band.

Her serious eyes studied mine, absorbing. She said, Your eyes are grey.

I nodded.

She asked, How’d you get to play upstairs?

I asked Art if I could.

A tall man carrying a sax case came up to her and she said to me, See you, and left the club with him. I went back to my room at the Y alone and felt the city humming outside and I made up a new set list. Coryell’s audience liked technical and complicated. I decided to play Mingus. Bud Powell. I lay in bed and wished I could fall into a dark crack. What if I was a zero in New York? What was I good for? Saint-Antoine joints. This was why men slouched around Times Square. They were so lonely they could die.

The next night I went back to the Gate and wore jeans and a coral camisole and my hair loose like Katherine and hoop earrings like hers that I bought on the street. I ramped it up and the chatter dropped away and people listened. Magic.

Art said, You got them tonight.

Sunday night I saw Katherine listening from the doorway. Near the end of my set, I stood up and said to the crowd, Can you believe it? Katherine Goodnow is here. Come up and play.

Everyone stopped talking and looked around, afraid to miss someone famous though they didn’t know who she was. Katherine was a real performer. She blinked the surprise out of her eyes and she walked right up like a star. I slid over and she sat down on the bench beside me and I played “Autumn Leaves” and she spread her large hands over the keys and started to riff, and we were listening to each other like crazy and we played some Brubeck and we started cutting a little, showing off. We were bumping elbows, we needed two pianos, and the audience was into us.

Art said, They dug you two. Want to play next week?

Of course we did.

Katherine said to me, You got time for coffee?

I had time for everything. My bed in the Y was the last place I wanted to be.

The stars were faraway New York glitter that night, eighty-eight constellations, eighty-eight piano keys. We walked to the Surf Maid and listened for a while, and then she said, Let’s go to my place. I got kids. Come upstairs.

Her apartment was all kitchen table. She threw her hat into the sink, slipped into the children’s bedroom, came out, asked, Where’re you from?

She made instant coffee with hot water from the tap and we talked about music and Hamilton and Montreal. It was her first few months in New York. She said, I play anywhere they pay me. Where did you hear Mo Billson’s band?

At the library at McGill. You were playing with a sax. It was great.

I haven’t thought about that for years.

I never heard the piece before. What’s it called?

I wrote it. It’s called “Tell a Woman-Lie.” The sax is the father of my kids.

I told her I had a lover in Karachi. She said, Well, lovers aren’t always around.

She put on Coltrane’s “Crescent,” very low, which I had never heard, and that was the night that I knew how I wanted to live. With musicians. I would write songs. I would stay up all night with strangers and listen to music and earn a living in music and I would be part of the unfurling beauty of the world. I looked through the window at the streaky black-blue of the Village and the flashing neon outside, my hands cupped around a stained mug full of instant coffee. It was three in the morning and Katherine said, I gotta get some sleep. You can stay here if you don’t want to walk back to the Y.

She showed me her double bed behind a curtain in the living room. She said, Do you want a T-shirt to sleep in? and handed me one from a laundry basket in the corner of the room.

She said, Sometimes in the winter and sometimes in the fall, I slip between the sheets with nothing on at all.

I reached for the shirt and she said, My ma used to say that when I was putting on my pyjamas.

I brushed my teeth with my finger while she looked in again on her sleeping children and then got into bed beside me. She rolled over and said, We should play together again. Her breath lengthened and she was gone. That was how Katherine fell asleep. Like a penny in a fountain.

Those cold New York Christmas weeks. I wandered around the Village. I wandered uptown. I walked in Central Park. I went out every night to listen to music. Katherine asked, You got anywhere to go for Christmas? and invited me to join them. I bought a game called Monopoly because a store clerk told me children here liked it and I bought oranges and chocolate because there were pictures of these things in a Christmas basket in the subway, and when I arrived Katherine had decorated a tiny tree in their apartment and Jimmie knocked it over but it was small and I took down a picture and tied it to the nail. I helped her make dinner, a turkey with bread and butter and celery and an apple inside. Katherine said, This bird cost me a fortune, thank goodness you brought dessert. T came in and he filled the rooms and his children were happy he was there and they tussled about who was sitting next to him. He went to Katherine and stood behind her and put his arms around her and said, Merry Christmas, babe, and it reminded me of how Mor and Abbu sometimes were all alone in a room in which they were not alone at all. I watched the children watching and I knew their feeling too, and I said to them, Give me your hands, I will teach you a Karachi love dance, and we made a ring around Katherine and T and ran around them while I sang the Beatles song, Love, love, love and after dinner we played Monopoly and at the end of the evening everyone said it was lucky that I came for their first New York Christmas and I said I was lucky to be with them for my first Christmas ever. The next day, I got Art to give Katherine and me a gig for February. I asked him, Two pianos?

I can’t get another piano up there.

I’ll bring something.

Suit yourself.

Katherine said, Great. I need to get work as a sideman and make some money. I need to get Bea new ballet slippers, she’s out of hers. How much is Art paying? You can stay here if you don’t mind the floor.

She was doing it all.

Back in Montreal, Jean heard the new licks I’d learned from Katherine. He winked, said, Been playing Little Burgundy?

His hair was longer and he tied it back now at the bottom of his neck. He said, I’ve got a gig for us to play the Esquire Club on Monday nights.

I said, I can do that. I played the Village Gate in New York, and I have another gig there next month.

That stopped his ironic winking. He said, Come for coffee, I want to hear all about it.

I acquired one of the first Minimoog Ds because it was portable and I liked Sun Ra. Monique and I had parties, made cheap soups and saffron vegetable biryani. Jean always arrived with his double bass and stayed to the end and smoked and drank a lot and wanted me to play with him which was fine with me. One night an actor tried to stay. He said to me, I think I am falling in love. I said, You’re drunk. Help me clean up.

I gave him a broom. I was picking up all the dishes and empty bottles and the place smelled of spilled beer and smoke and Jean was sitting in the kitchen with tea trying to stay awake. I told him to go home too, but he said, I’m not leaving you alone with that guy. By the time I finished the dishes the actor had wandered down the hall and passed out in my bed and I looked at him and thought, I can’t move him, so I went back to sleep on the couch but Jean was sleeping there. I put a coat over him and he stirred and took my hand and said, Mahsa, come here. I said, Go back to sleep. You’re my teacher. I figured he would not remember in the morning. He slept with a lot of students, but I was the one he played regular gigs with. Young men were drawn to me here and this was a novelty. Everyone was experimenting with each other and there was no one to stop me and it felt good to be desired. When boys flirted with me, I always thought about Kamal. I wished I could go to Karachi, stay for an hour or so, then come back. Monique was working at the Centaur Theatre. Creeps had opened and she was writing her own play called Simone et Jean-Paul for the Rideau Vert. It began with Simone de Beauvoir earning a second in her philosophy agrégation exam because the committee downstage secretly decided to give first prize to Sartre. They said a man needed it more for his career. Simone walked toward the audience and stage-whispered: Man is condemned to freedom and woman is condemned to be second. Marriage is a worn-out patriarchal oppression, a three-legged race.

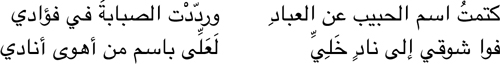

I did not see any subtlety in Monique’s writing but she said that it was not the time for subtlety. The women in the audience laughed and stomped. Monique said, Do the music for my next play, so I began to design stage music. I learned what the synthesizer could do and played and recited Arabic poetry at home for our parties while everyone smoked dope. Jean jumped up, said, Now I understand Persian, and danced with someone’s scarf. He got a recording gig for us with Metamusic. He played double bass and produced. It was my first recording since Abbu’s little 45. We started with me reciting from Ulayya bint al-Mahdi, whose brother forbade her to say the names of her slave-lovers in her songs.

I held back the name of my love, repeating it to myself.

I long for an empty space to call out the name of my love.

We ordered one hundred cassette tapes, gave them to friends, left them at record stores, sent them to radio stations. I mailed one to Katherine. She mailed back a new set list for the summer and said she was juggling too much, that I should recite poetry in New York too, signed off, Peace, baby. I played once a month with Katherine at the Village Gate and I slept on her floor. Jimmie started getting sent home from school and once she smashed a cup in the sink and sat down and cried at the kitchen table. I looked at her kids and they looked at me and finally Katherine said, Jimmie, what the hell are we going to do? He was too worried to say anything and then Katherine popped her head up as if nothing had happened and said, Let’s teach Mahsa to skate!

So we went to Central Park and rented ice skates at the Wollman Rink and I tried skating for the first time. Dexter and Bea held me up while I shuffled on those absurd little blades. I liked sledding better. Jimmie was sullen and sat on a bench. Katherine said, I don’t know what gets into him. Ever since the move. I guess he thought T might live with us. I got to keep him out of bad stuff.

I let Jimmie play on my Minimoog and we jammed. He had a great sense of rhythm, like Katherine. I cut my hair myself and I got Jimmie to hold the mirror. I cut it like Mick Jagger but I left it long enough that I could wear it up when I wore my sari. Now I had two looks. Downstairs there had been a benefit for Timothy Leary and everyone came to the Village Gate and I was happy to be playing there. I loved those New York weekends and arriving at the Port Authority Bus Terminal and my first smell of bagel and exhaust. Katherine said, I’m going to get us a recording gig for two pianos. I’ll send you the charts.