Chapter 12

Bend it, Stretch it, Any Way You Want to

A child[’s] … first geometrical discoveries are topological … If you ask him to copy a square or a triangle, he draws a closed circle.

– Jean Piaget

Topology is precisely the mathematical discipline that allows the passage from local to global.

– René Thom

There’s an old joke that asks: what is a topologist? The answer: someone who can’t tell the difference between a doughnut and a coffee cup – or, more to the point, who doesn’t care about the difference. In topology, a doughnut and a coffee cup shape are equivalent because (assuming they were made of something like clay) the one could be gradually deformed into the other: the handle deformed into the hole in the doughnut and the rest of the coffee cup gradually morphed into the ring around it. ‘Hole’ here has a specific meaning. A hole in topology must have two ends and pass all the way through, as it does in the case of a doughnut shape, or, to give it its formal name, a torus. What sometimes in everyday language is called a hole, such as one dug in the ground, isn’t a hole to a topologist because it doesn’t have two openings and can be gradually deformed until it’s completely filled in. In a nutshell, then, topology is the study of properties that stay the same if something changes in shape without having a hole put in it or being cut. It’s a modern extension of geometry that gives rise to a lot of weird results and pops up in all kinds of unexpected places.

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to a trio of British scientists, Duncan Haldane, Michael Kosterlitz, and David Thouless, for their work on so-called exotic states of matter. Under certain conditions, such as very low temperatures, a material can undergo a sudden, unexpected switch in behaviour. One morning in February 1980 a German physicist, Klaus von Klitzing, was experimenting with a supercooled, ultrathin sliver of silicon in a powerful magnetic field when he noticed something bizarre. The silicon had begun conducting electricity only in packets of certain sizes: a smallest-sized packet, a packet exactly twice as big, one three times as big, and so on, or nothing at all – there were no in-between amounts as you get with an ordinary electrical current. This phenomenon is known as the quantum Hall effect, and von Klitzing won the 1985 Nobel Prize in Physics for shedding new light on it. Evidently, the silicon had jumped into some new physical state, in which, as happens whenever there’s a change of state, there must have been a rearrangement of atoms. Theorists, however, struggled to explain how such a rearrangement could take place in a layer of silicon so thin that the atoms within it had no room to move up or down. Then Kosterlitz and Thouless came up with a novel idea. As the silicon cooled, they suggested, swirling pairs of silicon atoms formed and then spontaneously separated into two miniature vortices at the critical temperature of the transition. Thouless set to work on the maths behind these spinning transitions and found that it could best be formulated in terms of topology. The electrons in the material undergoing the change were forming what’s known as a topological quantum fluid, a state in which they flowed collectively only in whole numbers of steps. Working independently, Haldane found that these fluids can spontaneously appear in ultrathin layers of semiconductors even in the absence of strong magnetic fields.

After the announcement of the 2016 Prize in Stockholm, a member of the Nobel committee stood up and drew from a paper bag a cinnamon bun, a bagel, and a (Swedish) pretzel. These were different, he pointed out, in a number of ways – in flavour, for instance, sweet or salty, and general appearance. But to a topologist only one of their differences mattered: the number of holes – 0 in the bun, 1 in the bagel, 2 in the pretzel. The winners of the Prize, he explained, had found a way to link the sudden appearance of exotic physical states to changes in topology – effectively, the ‘hole-iness’ of the underlying abstract structures. In doing so they’d found a new and tremendously important application for a subject that has spawned some of the most surprising results in mathematics.

Take two prints of the same picture. Put one of them down flat on a table, then crumple up the other, any way you like, providing you don’t actually tear it, and place it somewhere on top of the uncrumpled print. It’s an inescapable fact that at least one point on the crumpled copy will lie directly over the corresponding point on the flat picture. (Strictly speaking, the maths we’re talking about here deals with continuous quantities whereas in the real world matter is grainy because it’s made of atoms and so forth, but the result is still valid to a very good approximation.) The same thing is true in three dimensions, so if you stir a glass of water, for however long you like, at least one water molecule will be in the same position after stirring as before. The first mathematician to publish a proof of this was the Dutchman Luitzen Brouwer, in the early years of the twentieth century, and so it became known as Brouwer’s Fixed Point Theorem.

Another curious result first proved by Brouwer, in 1912, though it had been proposed earlier by the prolific French mathematician Henri Poincaré, is the Hairy Ball Theorem. This states that no matter how much you comb a ball entirely covered with hair, it’s impossible to make the hair lie flat at every point: somewhere it must be sticking straight up. Brouwer (and Poincaré) didn’t actually talk about hairy balls, but less evocative stuff about continuous vector fields tangent to a sphere that must have at least one point where the vector is zero (at right angles to the sphere). But it amounts to the same thing. In more practical terms, because the velocity of wind along the Earth’s surface is a vector field, the theorem guarantees that there has to be somewhere on the planet where the wind isn’t blowing. Another truism, closely related to the Fixed Point Theorem and known as the Borsuk–Ulam Theorem, has something else to say about meteorological conditions: at any given moment, there exist two points on opposite sides of the planet with exactly the same temperature and barometric pressure. You might say that this is likely to happen quite a lot just by chance, but the Borsuk–Ulam Theorem guarantees mathematically that it’s bound to be the case.

Yet another strange-but-true fact follows from the Borsuk–Ulam Theorem – the so-called Ham Sandwich Theorem. Make a sandwich from ham and cheese, and this result says that it’s always possible to slice the sandwich in such a way that the two parts have an equal amount of bread, cheese, and ham. In fact the three ingredients don’t even have to be touching: the bread could be in the bread-bin, the cheese in the fridge, and the ham on the kitchen counter. Or, for that matter, they could be in different parts of the galaxy. There’s always going to be one flat slice (in other words, a plane) that bisects each one of them.

All these strange theorems – Fixed Point, Hairy Ball, Borsuk–Ulam, and Ham Sandwich – have sprung from the fertile ground of topology – tópos being the Greek for ‘place’ or ‘locality’. It’s a subject that, in daily life, we don’t generally hear much about. Everyone’s familiar with geometry – the subject, with ancient origins, which deals with the shape, size, and relative position of figures such as triangles, ellipses, pyramids, and spheres. Topology is related to geometry and also to set theory, and, as we’ve mentioned, has to do with properties that stay the same even when a figure is bent or stretched out of shape – properties known as topological invariants. Examples of such invariants include the number of dimensions involved and the connectedness, or how many separate pieces of which something is comprised.

The origins of topology can be traced back to the seventeenth century when the German polymath Gottfried Leibniz raised the possibility of dividing geometry into two parts: geometria situs, the geometry of place, and analysis situs, the analysis or taking apart of place. The former, which pretty much covers the geometry we learn about in school, deals with familiar concepts such as angles, lengths, and shapes, while analysis situs is concerned with abstract structures that are independent of those concepts. The Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler subsequently published one of the first papers on topology, in which he showed that it was impossible to find a way around the old seaport city of Königsberg in Prussia (now Kaliningrad in Russia) that would cross each of its seven bridges exactly once. The result didn’t depend on measurements, such as the lengths of the bridges or how far they were apart, but only on how they were connected with the land, either with islands in the river or the riverbanks. He found a general rule for solving such types of problems and in doing so gave birth to a new field of study, within topology, called graph theory.

The seven bridges of Königsberg across the River Pregel.

Euler also discovered a now-famous formula for polyhedra (3D solids with flat polygonal faces): v – e + f = 2, where v is the number of vertices (corners), e the number of edges, and f the number of faces. Again, the result is topological because it involves properties of geometric forms that don’t depend on measurements.

A Möbius band: a shape with only one ‘side’ when embedded in 3D.

Another pioneer in the field was August Möbius with his explorations of a band with a half-twist that now bears his name, though his compatriot Johann Listing published his own findings on the band a few years before Möbius, in 1861. If a strip of paper is twisted through 180° and then has its ends glued together, the result is a shape with only one surface – a fact easily demonstrated by drawing a pencil line all the way around the middle of the band until it joins up with the starting point. The act of joining the ends of the band following a half-twist makes a Möbius band a different beast in the eyes of a topologist from an ordinary band or open-ended cylinder. Whenever a shape is torn, or the ends of it are joined together, it becomes topologically something new. This fact leads to another feature of topology: it is well suited to describing sudden jumps in the state of a system, as the winners of the 2016 Nobel Physics Prize discovered.

In ordinary geometry, all figures are treated as being rigid and non-interchangeable. A square is always a square, a triangle always a triangle, and the one can never mutate into the other. Straight lines must stay perfectly straight and curves remain curves. However, in topology, shapes are allowed to lose their structure and become flexible while remaining essentially the same, providing they aren’t cut at any points or have separate parts joined together. For example, a square can be stretched and deformed until it becomes a triangle, yet in topological terms be unchanged: they’re said to be homeomorphisms. Likewise, both are identical to discs (circles with a solid interior). In three dimensions, a cube is homeomorphic to a ball (a sphere with a solid interior). In other words, the surface of a cube is topologically identical to that of a sphere. However, a torus or doughnut shape is fundamentally different from a sphere and no amount of stretching will make them the same.

The number of holes in a shape is known as its genus. So, a sphere and a cube have genus 0, an ordinary doughnut-shape genus 1, a two-holed torus genus 2, and so on. Three-dimensional topology can also take into account more complex factors, such as the structure of the surrounding space, which is what allows knots to form. Confusingly, in knot theory, most knots that we learn to tie are not knots at all. A mathematical knot differs from a knot in, say, a shoelace or a rope because its ends are joined together, so that it can’t be undone.

One way to think of a true knot is as a circle or any other closed loop inhabiting 3D Euclidean space. No amount of stretching or twisting will serve to untie it. The only way to make a true (mathematical) knot from a piece of string is to join the ends by, for example, taping them together. Using this method the simplest knot is the unknot, which is just a plain loop. After this, things get more complicated.

The simplest nontrivial knot is the trefoil knot, which is the kind that people often make if you ask them to tie a knot in a piece of string and if the ends are then joined together. More complex is the figure-of-eight knot or those formed from a combination of several basic knots. Two common examples are the square knot, also known as the reef knot, and the granny knot, both formed from two trefoil knots.

The first person to take an interest in knots from a mathematical point of view was the German Carl Gauss in the 1830s. He came up with a way to calculate the linking number – a number which, in the case of two closed curves in 3D, tells how many times the curves wind round each other. Links, like knots, have a central place in topology. Mathematical knots and links crop up in nature too, in electromagnetism and quantum mechanics, for instance, and in biochemistry.

Just as there’s an unknot, there’s an unlink, which is just two separate circles that aren’t joined in any way. Knots are simple links consisting of a single circle, but more complex links are possible by adding more circles. The Hopf link, consisting of two circles linked together once, is named after the German topologist Heinz Hopf, although Gauss had studied it a century earlier and it has long figured in artwork and symbolism. The Buzan-ha, a Japanese Buddhist sect founded in the sixteenth century, used it in its crest. More interesting are the Borromean rings, which employ three circles. What makes these unusual, and at first sight seemingly impossible, is that although no pair of circles is linked in any way, all three are. This means that if any of the three rings are removed, no matter which one is chosen, the other two can then be easily separated. The name comes from the Italian noble family of Borromeo, who used this link as part of their coat of arms, but the symbol dates back to antiquity. It crops up in Viking artefacts in the form of three interlocking triangles known as the Walknot (meaning knot of the slain) or Odin’s triangle. The motif also appears in various religious contexts, including old Christian church decorations where it symbolises the holy trinity.

Knots and links have been found in the chemistry of life itself. Proteins are well known for their ability to fold into certain specific shapes, which are crucial to the way they function in biological systems. What came as a surprise to biologists was the discovery, starting in the mid-1990s, that they can fold to become knotted, and may even form linked rings. Everyday knots call for some kind of threading to be done intentionally. It was hard to see how a protein could spontaneously self-assemble and, at the same time, manage to put a knot in itself. In fact, most mathematical models used to predict the outcome of protein folding, based on energy considerations, explicitly threw out any structures that were knotted because they were thought to be impossible. It’s an ongoing issue for researchers to understand how knotted proteins fold – and why.

At the start of 2017, a team of chemists from the University of Manchester announced that it had created the tightest knot ever seen. Made from 192 atoms linked in a chain, the knot was a mere two millionths of a millimetre wide – about 200,000 times thinner than a human hair. The atoms, of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, formed a strand which crossed itself eight times and curled around into a circular triple helix. Between each crossing point, the distance that defines the tightness of the knot, were just 24 atoms.

Other unexpected topologies have been found in the scientific world, one of the most surprising of which is the Möbius band, mentioned earlier. In 2012, chemists at the University of Glasgow reported that they had turned a symmetric, ring-shaped molecule into an asymmetric one by adding a molybdenum oxygen unit, with the formula Mo4O8, into the ring. The effect of introducing the new unit was to give the ring a half-twist, thereby producing a Möbius topology.

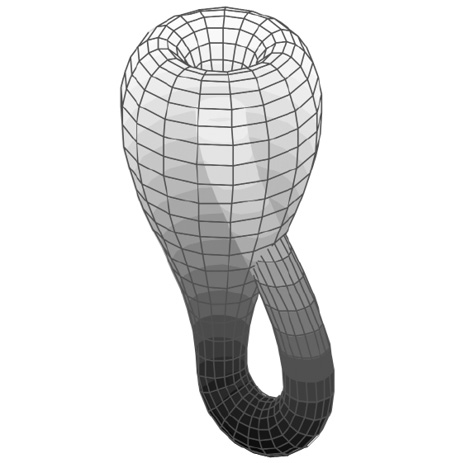

Making a Möbius band can literally be child’s play. But this isn’t the case with another one-sided surface known as the Klein bottle, after the German mathematician who first described it, Felix Klein. It may originally have been called Kleinsche Fläche, meaning the Klein surface, which then got passed along erroneously as Kleinsche Flasche, the Klein bottle. In any event, the latter name has stuck and may have helped give the object wider recognition, despite ‘surface’ being a better description.

Unlike the Möbius band, the Klein bottle has no edges or boundaries, a property it shares with the sphere. But unlike a sphere, the Klein bottle doesn’t have an inside and an outside – the two are identical – because there’s just a single surface folded back on itself. We’re not used to this kind of thing. In the real universe, we’re accustomed to objects, such as bubbles, boxes, and bottles of Beaujolais, having a well-defined interior and exterior, so that they enclose a certain volume of space. But because the Klein bottle doesn’t separate space into two different regions, it encloses nothing and therefore has zero volume.

A Klein bottle immersed in 3 dimensions. The ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ are, in fact, the same side. This cannot normally be achieved (there is no embedding into 3D), so the Klein bottle must intersect itself.

Spheres, tori, and Möbius bands are all examples of two-dimensional surfaces that can be ‘embedded’ in three-dimensional space. Embedding has a precise mathematical meaning but in everyday terms it can be thought of as sticking one space inside another, different, space. It’s important to keep in mind that spheres, Möbius bands, Klein bottles, and other geometrical objects are abstractions with properties that don’t depend on the nature of the space they’re put into – how many dimensions it has, whether it’s flat or curved, and so on. But certain things about them do change from one embedding to another. For example, a torus can be embedded in 3D, which is how we normally encounter it, and it then appears with a hole – a true mathematical hole – and an inside and outside.

Some readers may be old enough to remember the classic arcade game Asteroids. In this, the player controls a spaceship and tries to knock out wayward asteroids and occasional flying saucers that pass by. At first glance, this seems to have nothing at all in common with the familiar doughnut-shaped ring torus. However, topologically, they are one and the same – both are toroidal. The hole in a doughnut is a feature caused by the embedding of a torus in 3D, and isn’t an inherent property of all tori. In Asteroids space, the underlying toroidal topology manifests itself, not as a hole, but as the ability of things that disappear off one side of the screen to immediately reappear on the opposite side. A torus can also be embedded in 4D and one of the possible outcomes of this is the Clifford torus, named after the Victorian mathematician William Kingdon Clifford, who was also the first person to suggest that gravitation might be an effect of the geometry of the space in which we live. Unlike the ring torus that we know well, with its clearly defined interior and exterior, the Clifford torus doesn’t divide space and so can’t be said to have an inside and an outside.

The same is true of the Klein bottle. The Austrian-Canadian mathematician Leo Moser described, in the form of a limerick, how the original idea for this shape came about:

A mathematician named Klein

Thought the Möbius band was divine.

Said he: ‘If you glue

The edges of two,

You’ll get a weird bottle like mine.’

This is why the Klein bottle has no edges – when the edges of two Möbius bands (a left and a right) are brought together they form one continuous surface that is smoothly connected at all points. Another way to make a Klein bottle is to start with a rectangle, join one pair of opposite sides to make a cylinder, and then join the other pair of sides after making a half-twist. This second step, simple as it sounds, is actually impossible in three dimensions. Access to a fourth is needed in order that the surface can be made to pass through itself without a hole. That little difficulty doesn’t stop people making 3D models of Klein bottles that are nearly but not quite accurate representations. Notable experts of the art are Clifford Stoll, of Oakland, California, who runs the Acme Klein Bottle company, and Alan Bennett, of Bedford, England, who fashioned a series of Klein bottles, analogous to Möbius bands with odd numbers of twists greater than one, for the Science Museum in London. What these craftsmen have created are known by mathematicians as 3D ‘immersions’ of Klein bottles. The distinction between an immersion and an embedding is a technical one but what it boils down to is that a 3D model (an immersion) of a Klein bottle will always have a point of self-intersection where the surface passes through itself. A true Klein bottle has no such self-intersection and, indeed, none is present in a 4D embedding of it.

Another important feature of the Klein bottle, and of any surface, is its orientability. Most surfaces we meet in the physical world are said to be orientable. What this means is that if you were to draw a small circular arrow on the surface, pointing either clockwise or anticlockwise, and then slide the arrow all the way round the surface and back again to where it started, it would still point in the same direction. This would happen on a sphere or torus, for example, so these are orientable surfaces. But try the same experiment with a Klein bottle or a Möbius band and the arrow would have reversed its direction because these are non-orientable surfaces.

Topologists spend a lot of time flitting, in their mind’s eye, between spaces of different dimensions. So they’ve come up with their own vocabulary to be able to generalise about things as they do this dimension-hopping. ‘Embedding’ and ‘immersion’ are a couple of terms used in this respect; another is ‘manifold’, which is a generalisation of the term ‘surface’ to other dimensions. By definition, surfaces are two-dimensional, so rather than say ‘2D surface’ (which is tautological) we should really say ‘2D manifold’. Spheres, tori, Möbius bands, and Klein bottles are all examples of 2D manifolds. The first three of these can be embedded in 3D but not the Klein bottle. Lines and circles are 1D manifolds, and, although we can’t visualise them properly, there are 3D manifolds, 4D manifolds, and so on. One of the simplest 3D manifolds is the 3-sphere. Just as an ordinary sphere, or 2-sphere, is a surface that forms the boundary of a ball in three dimensions, a 3-sphere is an object with three dimensions that forms the boundary of a ball in four dimensions. We can’t accurately imagine what the 3D analogue of a surface might look like, let alone boundaries in even larger numbers of dimensions. But, despite this handicap, mathematicians have all the tools they need to deal with them.

Working in higher dimensions springs some surprises. In 4D, for instance, circles can’t be linked and ordinary knots don’t exist. The same is true in all higher dimensions. Something else very bizarre happens in four-dimensional space: spheres themselves can become knotted. We can’t visualise this but then the idea of circles being knotted without self-intersecting would be impossible for two-dimensional beings to imagine.

Like all other areas of mathematics, topology is a dynamic subject in which new discoveries are being made every year and problems, old and new, remain to be solved. One of the most important notions in topology, and in maths as a whole, is known as Poincaré’s conjecture. It isn’t important because of any obvious practical applications. It won’t, so far as we know, help us get to Mars faster or find a cure for ageing. Its interest to mathematicians is purely theoretical, as part of the effort to classify higher-dimensional surfaces, or manifolds.

The conjecture was first put forward in 1900 by Henri Poincaré, one of the founders of topology as a precise discipline and regarded by some as the ‘last universalist’, in that he was an expert in all the areas of maths as they existed during his lifetime. Poincaré came up with a technique called homology, which, loosely speaking, is a way of defining and categorising holes in manifolds. This isn’t as straightforward as it may sound because mathematical holes can be sneaky things that aren’t as easy to spot and count as the ones in, say, a pretzel or an old sock. The two-dimensional space in Asteroids, for example, is topologically equivalent to a torus, although a torus appears to clearly have a hole whereas the Asteroids space doesn’t seem to have any. Keep in mind that mathematical holes are abstract things that can be harder to imagine than, say, a hole in a doughnut and also that they are surrounded by ‘loops’, so that homology can also be defined as a way of analysing the different types of loops in manifolds.

Poincaré’s original conjecture was that homology was enough to tell whether any given three-dimensional manifold was topologically equivalent to a 3-sphere. However, within a few years he himself disproved this by finding the Poincaré homology sphere, which isn’t a true 3-sphere but has the same homology as it. After further research, he restated his conjecture in a new form. In plain language it says that any finite 3-dimensional space, providing it has no holes in it, can be continuously deformed into a 3-sphere. Despite much effort during the twentieth century, the conjecture went unproven. So important was it considered to be that, in 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute listed it as one of seven major problems a solution to which would win a million-dollar prize. Three years later, the conjecture was proved correct by the Russian mathematician Grigori Perelman as a consequence of his proof of a closely related problem called Thurston’s geometrisation conjecture.

In 2005, Perelman was awarded the Fields Medal – arguably the most prestigious honour in mathematics and often considered to be equal in stature to a Nobel Prize. Then, in 2010, came the announcement that he had met the criteria for the $1,000,000 Clay Institute Prize. However, he turned down both these awards, apparently on ethical grounds. Firstly, in his view, they didn’t acknowledge the important contributions of others, notably the American mathematician Richard Hamilton, whose work Perelman had built upon. He was also unhappy about what he considered to be a lack of good conduct by some researchers, especially the Chinese mathematicians Zhu Xiping and Huai-Dong Cao, who, in 2006, published a verification of the Hamilton–Perelman proof but seemed to imply that the proof was actually their own work. They later retracted their original paper, titled ‘A Complete Proof of the Poincaré and Geometrization Conjectures – Application of the Hamilton–Perelman Theory of the Ricci Flow’, and issued another with more modest claims. But the damage had been done as far as Perelman was concerned: he was dismayed by their behaviour and also by the lack of criticism of it by others in the field. In an interview given to The New Yorker in 2012, he said: ‘As long as I was not conspicuous, I had a choice. Either to make some ugly thing [a fuss about the ethical breaches he perceived] or, if I didn’t do this kind of thing, to be treated as a pet. Now, when I become a very conspicuous person, I cannot stay a pet and say nothing. That is why I had to quit.’ Whether Perelman has now permanently retired from mathematics or is quietly working on other problems isn’t clear. Certainly, he is not one to enjoy the limelight. ‘I’m not interested in money or fame,’ he said after being awarded the Clay Institute prize. ‘I don’t want to be on display like an animal in a zoo.’ His place in history, however, is assured having finally settled one of the most important and difficult questions in topology.

Another well-known thorn in the side of topologists goes by the name of the triangulation conjecture and it, too, has recently been resolved – but this time in the form of a disproof. In plain English, the issue is whether or not every geometric space can be divided into smaller pieces; the triangulation conjecture proposes that it can. In the case of a sphere, for instance, it’s possible to completely tile its surface with triangles. A regular icosahedron – a polyhedron with 20 sides made of equilateral triangles – is a rough approximation to a sphere, but we can improve on this indefinitely by using as many triangles as we like and of any shape. A torus can be ‘triangulated’ in the same way. A three-dimensional space can be sliced up into an arbitrary number of tetrahedrons. But is it possible to triangulate geometric objects in all higher dimensions with higher-dimensional equivalents of a triangle? In 2015, Ciprian Manolescu, a Romanian mathematics professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, managed to prove that it isn’t. Manolescu, a child prodigy who is the only person ever to have racked up three consecutive perfect scores in the International Mathematics Olympiad, first encountered the triangulation problem as a graduate student at Harvard in the early 2000s. At the time he dismissed it as ‘an unapproachable problem’, but years later realised that a theory he’d written about in his PhD thesis, concerning something called Floer homology, was the very thing needed to resolve the issue. By bringing his earlier work to bear he managed to show that there are some 7-dimensional manifolds that have no triangulation, thereby disproving the triangulation conjecture. It was a remarkable feat given that, using other methods, even spaces of four dimensions are still too complex to analyse with respect to their triangulation.

In the early 1980s, the American geometer William Thurston, who died in 2012, envisioned a project that would identify every three-dimensional manifold. In two dimensions this had already been done. The 2-manifolds are the sphere, torus, two-holed torus, three-holed torus, and so on. To these we can add non-orientable surfaces, such as the Klein bottle and the projective plane (made by joining two Möbius bands of the same handedness along their edges). Thurston used a technique that allowed many of these 2-manifolds to be represented by polygons. For example, if you take a square and join opposite edges, the result is a torus. The two-holed torus is tougher to produce, but Thurston found a way. He represented a two-holed torus by joining certain pairs of edges of an octagon, which is embedded in the hyperbolic plane. This embedding avoids a difficulty that crops up if the octagon were Euclidean. In this case, the two-holed torus would have a single point common to all vertices of the octagon, which would have an angle sum of 1080 degrees and not 360 as is required. In hyperbolic geometry – geometry on saddle-shaped surfaces, or, more precisely, ones that curve the opposite way to a sphere and at a constant rate – octagons of the correct size can have angles of 45 degrees, thereby fixing the problem.

Thurston tried to do a similar thing in three dimensions. In 2D there are three types of uniform geometry: elliptic, Euclidean, and hyperbolic. The elliptic and Euclidean geometries can easily be embedded in space, but hyperbolic geometry can’t, which is why it wasn’t discovered until much later. In 3D, all three of these geometries have an analogue, but there are also some others, for a total of eight geometries. Of these, the hyperbolic one is the most complex and hardest to work with, just as it is in 2D. In 2012, Ian Agol managed to enumerate all of the hyperbolic manifolds (then the only unsolved case). His methods involved techniques that at first sight appeared to bear no relation to the original problem, such as using complexes made of cubes of various dimensions and analysing the hyperplanes that bisect these cubes. These manifolds have real applications. For instance, some cosmologists have suggested that the geometry of the universe as a whole is elliptic and is a finite manifold, having the structure of a dodecahedron with certain faces identified. This manifold can be classified by Agol’s techniques.

Of course, there are still many unsolved problems in topology, and perhaps there always will be given that as the boundaries of the known are pushed back they reveal more of the extent of our ignorance. But topology is no longer the specialised and seemingly impractical subject it was a century or more ago. It has countless real-world applications, including robotics, condensed matter physics, and quantum field theory, and its ideas can be found in almost all areas of mathematics today.