Chapter 2

How to See in 4D

One of the strangest features of string theory is that it requires more than the three spatial dimensions that we see directly in the world around us. That sounds like science fiction, but it is an indisputable outcome of the mathematics of string theory.

– Brian Greene

We live in a world of three dimensions – up and down, side to side, and backwards and forwards, or any other three directions that are at right angles to each other. It’s easy to imagine something in one dimension, such as a straight line, or two dimensions, such as a square drawn on a sheet of paper. But how can we possibly learn to see in an extra dimension to those we’re familiar with? Where is this additional direction that’s perpendicular to the three we know?

These questions may seem purely academic. If our world is three-dimensional, why worry about 4D or 5D and so forth? The fact is that science may need higher dimensions to explain what is going on at a subatomic level. These extra dimensions may hold the key to understanding the grand scheme of matter and energy. Meanwhile, on a more practical level, if we could learn to see in 4D we’d have a powerful new tool to deploy in medicine and education.

Sometimes the fourth dimension is taken to be something other than an extra direction in space. After all, the word ‘dimension’, from the Latin dimensionem, means simply a ‘measurement’. In physics, the basic dimensions that form the building blocks of other quantities are considered to be length, mass, time, and electric charge. Very often, in a different context, physicists talk about three dimensions of space and one of time, especially since Albert Einstein showed that, in the world in which we live, space and time are always bound up together in a single entity called spacetime. Even before the theory of relativity came along, however, there had been speculation about the possibility of being able to move backwards and forwards along the dimension of time just as we can move any way we like in space. In his novel The Time Machine, published in 1895, H. G. Wells explains that an instantaneous cube, for instance, can’t exist. A cube that we see moment by moment is just a cross section of a four-dimensional thing having length, breadth, width, and duration. ‘There is no difference,’ says the Time Traveller, ‘between Time and any of the three dimensions of Space except that our consciousness moves along it.’

The Victorians were also fascinated by the idea of a fourth dimension of space, both from a mathematical point of view and in the possibilities it seemed to offer of explaining another obsession of the age – spiritualism. The late 1800s was a period when many people, including luminaries such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and William Crookes, were attracted to the claims of mediums and the prospect of communicating with the dead. Might the afterlife, people wondered, exist in a fourth dimension that was parallel to, or overlapped with, our own so that spirits of the deceased could pass easily into our material realm and back again?

Our failure to be able to visualise in higher dimensions makes it tempting to think that the fourth dimension is somehow mysterious or alien to anything we know. Mathematicians, though, have no trouble in working with four-dimensional objects or spaces because they don’t have to imagine what they’re actually like in order to describe their properties. These properties can be figured out using algebra and calculus without having to resort to any multidimensional mental gymnastics. Start with a circle, for instance. A circle is a curve made of all the points in a plane that are at the same distance (the radius) from a given point (the centre). Like a straight line, it has only length – no width or height – and so is a one-dimensional thing. Imagine yourself positioned and constrained within a line. The only freedom of movement you would have is along the line, one way or the other. It’s the same with a circle. Although a circle exists in a space of at least two dimensions, if you were positioned and confined within the circle then you’d have no more or less freedom of movement than if you were positioned on a line. You could only go back and forth along the circle, effectively tied down to a single dimension of movement.

Non-mathematicians sometimes think of a circle as including its interior as well. But a ‘filled-in circle’ to a mathematician isn’t a circle at all but a very different object called a disc. A circle is a one-dimensional object that can be ‘embedded’ in a two-dimensional object, a plane (a finely drawn circle on a sheet of paper is an approximation to this). The length, or circumference, of a circle is given by 2πr, where r is the radius, and the area enclosed by the circle is πr2. Moving up a dimension we come to the sphere, which consists of all the points lying at the same distance in three-dimensional space from a given point. Again, the layperson may confuse an actual sphere, which is just a two-dimensional surface, with the object that also includes all the points inside this surface. But, once more, mathematicians make a sharp distinction and call the latter a ‘ball’. A sphere is a two-dimensional object that can be embedded in three-dimensional space. It has a surface area of 4πr2 and encloses a volume of 4/3πr3. Because an ordinary sphere is two-dimensional, mathematicians call it a 2-sphere, whereas a circle, using the same naming system, is a 1-sphere. Spheres in higher dimensions are said to be ‘hyperspheres’ and can be labelled in the same way. The simplest hypersphere, the 3-sphere, is a three-dimensional object embedded in four-dimensional space. We can’t capture this in our mind’s eye but we can understand it by analogy. Just as a circle is a curved line and an ordinary (2-) sphere is a curved surface, a 3-sphere is a curved volume. Using some straightforward calculus, mathematicians can show that this curved volume is given by 2π2r3. It’s the 3-sphere equivalent of the surface area of an ordinary sphere and is also referred to as a cubic hyperarea or surface volume. The four-dimensional space enclosed by a 3-sphere has a four-dimensional volume, or quartic hypervolume, of ½π2r 4. Proving these facts about the 3-sphere is not much more difficult than proving them about the circle or ordinary sphere and doesn’t involve having to understand what a 3-sphere actually looks like.

In the same way, we may struggle to grasp the true appearance of a four-dimensional cube or ‘tesseract’, though, as we’ll see, we can try to represent it in two or three dimensions. But it’s straightforward to describe the progression from square to cube to tesseract: a square has 4 vertices (corners) and 4 edges; a cube has 8 vertices, 12 edges, and 6 faces; a tesseract has 16 vertices, 32 edges, 24 faces, and 8 ‘cells’ – the three-dimensional equivalents of faces – consisting of cubes. This last fact is the one that defies our attempts at visualisation: a tesseract has 8 cubic cells arranged in such a way as to enclose a four-dimensional space, just as a cube has 6 square faces arranged so as to enclose a three-dimensional space.

The best we can normally do in coming to terms with the fourth dimension is to draw analogies with the third. For instance, if we were to ask, ‘What would a four-dimensional hypersphere look like if it were to pass through our space?’ we can get an impression by considering what happens if a sphere passes through a plane. Suppose there are two-dimensional beings who inhabit that plane. Looking along the surface of their world – which is all they can do – they see only dots or lines of different length which they can only interpret as two-dimensional figures. As our 3D sphere initially makes contact with their 2D space they see it as a dot, which then grows into a circle reaching a maximum diameter equal to the diameter of the sphere before the circle shrinks again to a dot and then disappears, as the sphere passes through. Likewise, if a 4-sphere were to intersect our space we’d see it as a dot that expanded, like a bubble, into a three-dimensional sphere of maximum size before shrinking and finally vanishing. The true nature – the extra dimensionality – of the 4-sphere would be hidden from us, although its mysterious appearance, growth, and disappearance would probably cause us to wonder what was going on!

Four-dimensional beings would have seemingly magical powers in our world. They could, for example, pick up a right-footed shoe, flip it over in the fourth dimension, and put it back as a left-footed one. If this seems hard to understand, think of a two-dimensional shoe, which would be like an infinitely thin sole shaped for one foot or the other. We could cut such a shape out of a piece of paper, lift it up, turn it over, and put it back down, so that we changed its footedness. A 2D creature would find this utterly astonishing but to us, with the benefit of the extra dimension, the trick would seem obvious.

In principle a 4D being could flip around a whole (3D) person in the fourth dimension, although the absence of cases of people having suddenly had everything switched right-to-left or left-to-right, suggests that this hasn’t actually happened. In his short tale ‘The Plattner Story’, H. G. Wells describes the remarkable case of Gottfried Plattner, a teacher who disappears for nine days following an explosion in a school chemistry lab. Upon his return, he is effectively a mirror image of his previous self, though his recollections of what had happened during the period of absence are met with incredulity. Being flipped over for real in the fourth dimension would be bad for your health, apart from the shock of seeing yourself look different in the mirror (faces are surprising asymmetrical). Many of the crucial chemicals in our bodies, including glucose and most amino acids, have a certain handedness. Molecules of DNA, for example, which take the form of a double helix, always twist like a right-handed screw. If all these chemicals had their handedness reversed we’d quickly die of malnutrition because many of the essential nutrients in our food, from plants and animals, would now be in a form we couldn’t assimilate.

Mathematical interest in a fourth spatial dimension began in the first half of the nineteenth century with the work of the German Ferdinand Möbius. He’s best remembered for his study of a shape that’s now named after him – the Möbius band – and as a pioneer of the field known as topology. It was he who first realised that in a fourth dimension a three-dimensional form could be rotated into its mirror image. In the second half of the nineteenth century, three mathematicians stood out as explorers of the new realm of multidimensional geometry: the Swiss Ludwig Schläfli, the Englishman Arthur Cayley, and the German Bernhard Riemann.

Schläfli began his magnum opus, Theorie der Vielfachen Kontinuität (Theory of Continuous Manifolds), by saying: ‘The treatise … is an attempt to found and develop a new branch of analysis that would, as it were, be a geometry of n dimensions, containing the geometry of the plane and space as special cases for n = 2, 3.’ He went on to describe multidimensional analogues of polygons and polyhedrons, which he called ‘polyschemes’. These are now commonly known as polytopes, a term coined by the German mathematician Reinhold Hoppe and introduced to English researchers by Alicia Boole Stott, daughter of the English mathematician and logician George Boole, who devised Boolean algebra, and Mary Everest Boole, a self-taught mathematician and writer on the subject.

Also to Schläfli’s credit is the discovery of the higher-dimensional relatives of the Platonic solids. By Platonic solid is meant a convex shape (one with all the corners pointing outwards) with regular polygon faces and the same number of faces meeting at each corner. There are five of them: the cube, tetrahedron, octahedron, (12-sided) dodecahedron, and (20-sided) icosahedron. The four-dimensional equivalents of the Platonic solids are the convex regular 4-polytopes (also called polychora), of which Schläfli found there were six, named after the number of cells they have. The simplest 4-polytope is the 5-cell, which has 5 tetrahedral cells, 10 triangular faces, 10 edges, and 5 vertices, and is analogous to the tetrahedron. Then there is the 8-cell, or tesseract, and its ‘dual’, the 16-cell, obtained by replacing cells with vertices, faces with edges, and vice versa. The 16-cell has 16 tetrahedral cells, 32 triangular faces, 24 edges, and 8 vertices, and is the four-dimensional analogue of the octahedron. Two other 4-polytopes are the 120-cell, an analogue of the dodecahedron, and the 600-cell, an analogue of the icosahedron. Finally, there is a 24-cell, which has 24 octahedral cells and no three-dimensional counterpart. Interestingly, Schläfli found, the number of convex regular polytopes in all higher dimensions is the same – just three.

Through the work of Cayley, Riemann, and others, mathematicians learned how to do complex algebra in 4D and branch out into multidimensional geometries that went beyond the rules prescribed by Euclid. But what they still couldn’t do was actually see in four dimensions. The question was: could anybody? This was a problem that intrigued the British mathematician, teacher, and writer of scientific romances, Charles Howard Hinton. In his twenties and early thirties, Hinton taught at two private schools in England: first at Cheltenham College in Gloucestershire and then at Uppingham School in Rutland, where a fellow teacher – in fact, Uppingham’s first mathematical master – was Howard Candler, a friend of Edwin Abbott. It was during this period, in 1884, that Abbott published his now-classic satirical novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Four years earlier, Hinton had penned an article of his own on alternative spaces called ‘What Is the Fourth Dimension?’ in which he put forward the idea that particles moving around in three dimensions might be thought of as successive cross sections of lines and curves existing in four dimensions. We, ourselves, might really be four-dimensional beings, ‘and our successive states the passing of them through the three-dimensional space to which our consciousness is confined’. The extent of the relationship between Abbott and Hinton isn’t clear but they certainly knew of each other’s work (and acknowledged as much in their writings) and some social contact would have taken place, if only via their mutual friend and colleague. Candler would surely have discussed with Abbott the young teacher at Uppingham who wrote and spoke so openly about other dimensions.

Cover of the first edition of Edwin Abbott’s Flatland.

Hinton was nothing if not unconventional. At the time he was teaching in England, he married Mary Ellen Boole, daughter of the above-mentioned Mary Everest Boole (herself the niece of George Everest, after whom the tallest mountain is named) and George Boole. Unfortunately, three years into his marriage, Hinton also went through a secret wedding ceremony with another woman, Maud Florence, whom he’d met while at Cheltenham College and had twin children by. Probably the attitudes of his father, James Hinton, a surgeon and head of a sect devoted to polygamy and free love, played a part in Charles’ behaviour. In any event, Hinton was found guilty of bigamy at an Old Bailey trial and jailed for several days. With his (first) family he then fled to Japan, where he taught for some years, before becoming an instructor of mathematics at Princeton University. There, in 1897, he designed a species of baseball gun, which, with the help of gunpowder charges, fired out balls at speeds of 40 to 70 miles per hour. The New York Times in its March 12 edition of that year described it as, ‘a heavy cannon, with a barrel about two and a half feet in length, with a rifle attachment in the rear’. Its cleverest trick, throwing curveballs, was accomplished with the help of ‘two curved rods, which are inserted in the barrel of the cannon’. For a few seasons, the Princeton Nine used it, on and off, before abandoning it as a safety hazard. Whether the injuries it caused were a factor in Hinton’s dismissal from the college is unclear, but they didn’t prevent him reintroducing the machine at the University of Minnesota where, briefly, in 1900, he held a teaching post before joining the US Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C.

Hinton’s fascination with the fourth dimension, stretching back to his early days as a teacher in England, began at a time when others were writing about the subject and often speculating about its possible links with spiritualism. In 1878, Friedrich Zöllner, professor of astronomy at the University of Leipzig, published a paper called ‘On space of four dimensions’ in The Quarterly Journal of Science (edited by the chemist and prominent spiritualist William Crookes). Zöllner started on solid mathematical ground by referencing Bernhard Riemann’s seminal paper ‘On the hypotheses which underlie geometry’, published in 1868, two years after Riemann’s death and 14 years after its contents were first delivered as a lecture by Riemann while still a student at the University of Göttingen. Riemann developed the concept, first hinted at by his supervisor at Göttingen, the great Carl Gauss, that three-dimensional space could be curved (just as a two-dimensional surface, such as a sphere, can be) and extended this idea of the curvature of space into an arbitrary number of dimensions. The result, known as elliptic or Riemannian geometry, later formed a cornerstone of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Zöllner also borrowed the notion, described in an 1874 paper by the young projective geometer Felix Klein, that knots could be undone and rings unlinked simply by lifting them into a fourth dimension and turning them over. In this way Zöllner set the scene for his explanation of how spirits, existing, as he saw it, on a higher plane, could perform the various phenomena – especially the knot-untying tricks – that he’d witnessed at séance experiments with the famous (and, as it turned out, utterly fraudulent) medium Henry Slade. Hinton, like Zöllner, was inclined to think that mere habit of perception limited us to a three-dimensional viewpoint and that a fourth dimension might be all around us and become visible to us if only we could train ourselves to see it.

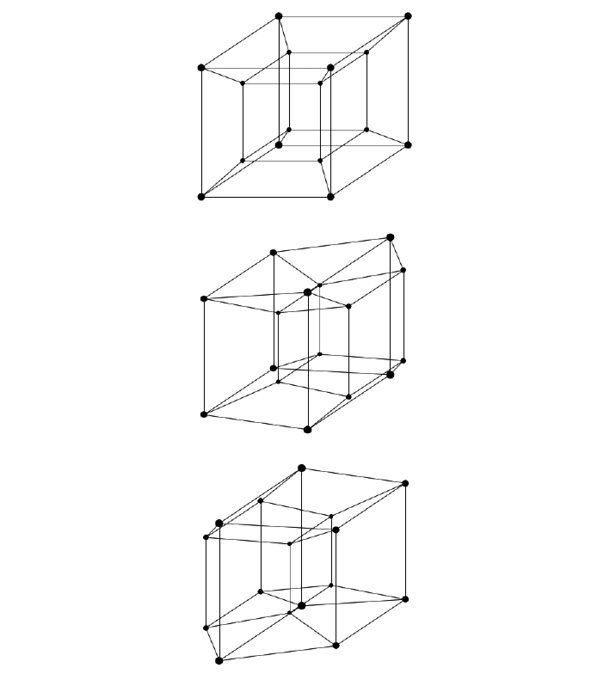

Although something that’s four-dimensional is hard to imagine, it’s easy to do a 2D sketch of one. This is especially true in the case of the four-dimensional equivalent of a cube for which Hinton coined the name ‘tesseract’. Start by drawing two squares, slightly offset, and connecting their corners by straight lines. This can be visualised as a perspective drawing of a cube, the squares being separated, in our mind’s eye, in the third dimension. Next draw two cubes joined at their corners. With 4D vision we’d be able to see this as two cubes separated in the fourth dimension – in fact, a perspective of a tesseract. Unfortunately, flat representations of 4D objects aren’t much help to us in being able to see them for what they really are. Hinton realised that a more fruitful approach to training our minds to see in four dimensions might be through three-dimensional models that could be rotated to show different aspects of a 4D shape: at least that way we’d only be dealing with a perspective of the real thing rather than a perspective of a perspective. To this end, he developed an intricate visual aid in the form of a set of one-inch wooden cubes in different colours. A complete set of Hinton cubes consisted of 81 cubes painted in 16 different colours, 27 ‘slabs’ used to represent, by analogy, how a 3D object can be built up in two dimensions, and 12 multicoloured ‘catalogue cubes’. By elaborate manipulations, described in detail in his book The Fourth Dimension, first published in 1904, he was able to represent the various cross sections of a tesseract and then, by memorising the cubes and their many possible orientations, gain a window on this higher-dimensional world.

Rotation of a tesseract. (Top) The traditional ‘cube within a cube’ view of a tesseract. (Centre) The tesseract has rotated slightly. The central cube has started to move and is in the process of becoming the right cube. (Bottom) The tesseract has rotated further and the central cube is now much closer to where the right cube was originally. Finally, the tesseract rotates fully back to its starting position. What is important is that the tesseract has not in any way deformed. Instead, the changes are due to a shift in perspective.

Did Hinton actually learn to create four-dimensional images in his brain? In addition to the familiar up and down, forward and back, and side to side, could he see ‘kata’ and ‘ana’ – his names for the two opposite directions along the fourth dimension? Without getting inside his head we can’t know. Certainly he wasn’t alone in building 3D representations of 4D shapes. He introduced his cubes to his sister-in-law, Alicia Boole Stott, who became an intuitive geometer of the fourth dimension herself and adept at making card models of 3D cross sections of 4D polytopes. The question remains whether, by such means, a person can develop true four-dimensional vision or just the ability to understand and appreciate the geometry of higher-dimensional objects.

In a way, being able to see an extra dimension is like being able to see a new colour – one outside all our previous experience. The French impressionist painter Claude Monet underwent surgery in 1923, at the age of 82, to remove the lens from his left eye, which had become hopelessly clouded by cataracts. Subsequently, the colours he chose to use in his art changed from mostly reds, browns, and other earthy tones to blues and violets. He even repainted some of his earlier works so that, for example, what had been white water lilies took on a bluish hue – an indication, it’s been claimed, that he could now see into the ultraviolet region of the spectrum. This idea is supported by the fact that the lens of the eye blocks out wavelengths shorter than about 390 nanometres (billionths of a metre), at the far end of the violet range, even though the retina has the potential to detect wavelengths down to about 290 nanometres, which is in the ultraviolet. There’s also plenty of evidence, in more recent times, of young children, and of older people who have missing lenses, being able to see beyond the violet end of the spectrum. One of the best-documented cases is that of a retired air force officer and engineer from Colorado, Alek Komarnitsky, who had a cataract-affected natural lens replaced by an artificial one that can transmit some UV light. In 2011, Komarnitsky underwent tests using a monochromator at a Hewlett-Packard lab where he reported being able to see wavelengths down to 350 nanometres, as a deep purple hue, and some variation in brightness even further into the UV, down to 340 nanometres.

Most of us have three types of cone cells – the kind responsible for colour vision – in our retinas. Most colour blind people, and many other types of mammal, including dogs and New World monkeys, have only two so that the number of different shades of colour they can see is restricted to about 10,000 compared to the million or so the rest of us can discern. Researchers have, however, found rare instances of individuals with four different working types of cone cells. These ‘tetrachromats’ can, according to estimates, distinguish almost 100 million more shades of colour than normal, although, since it’s natural for everyone to assume we all see the same, they may only gradually come to realise that they have this super-power, without special testing.

The point is, humans have the ability, in special circumstances, to see things that are outside the normal experiences that most of us have. If some people can see in ultraviolet, or subtler shades than usual, then why not the fourth dimension? Evidently, our brains can adapt to processing sensory information that we’re not normally used to receiving. Perhaps they can be trained to create internal images that are in 4D.

Today, we have a huge advantage in our efforts to visualise the world of four dimensions thanks to the availability of computers and other advanced technology. It’s easy now to create animations of a wire-framed tesseract, for example, to show how its appearance, as seen on a flat screen, changes as it’s rotated. Our brains still interpret what we see as the strange behaviour of a number of interconnected cubes, rather than anything in 4D. Yet we get an impression of something very unusual going on that can’t be explained in ordinary three-dimensional terms. Does the technology we have, or soon will have, hold the promise of letting us directly experience the fourth dimension?

One school of thought says that, despite the claims of people like Hinton, we can never really see in 4D because the world around us is unremittingly three-dimensional, our brains are three-dimensional, and evolution has equipped us to interpret all the sensations we receive as set in a 3D context. No amount of mental effort will help bring the particles that make up our bodies into a different plane of existence. Nor will any trick of engineering allow us to build a thing in 4D, such as an actual tesseract. This hasn’t stopped science fiction writers from imagining some strange combination of events that might cause a 3D object or system to spontaneously develop an extra dimension. ‘And He Built a Crooked House’, by Robert Heinlein, first published by Astounding Science Fiction in February 1941, tells the tale of an ingenious architect who designs a house with eight cubical rooms laid out like a net of a tesseract in 3D. Unfortunately, an earthquake shakes the building, shortly after its completion, and causes it to fold into an actual hypercube with bewildering results for those who first venture through its door. In ‘A Subway Named Moebius’ (1950), Boston’s underground train network becomes so convoluted that part of it flips into another dimension along with a train full of passengers, although all arrive safely at their intended stations in the end. Written by A. J. Deutsch, an astronomer at Harvard (one of the stops on the system), it plays on the themes of the Möbius band and Klein bottle, the latter being a one-sided shape that can exist only in four dimensions.

Artists too have tried to capture the essence of 4D in their work. In his 1936 Dimensionist Manifesto, Hungarian poet and art theorist Charles Tamkó Sirató claimed that artistic evolution had led to: ‘Literature leaving the line and entering the plane … Painting leaving the plane and entering space … [And] sculpture stepping out of closed, immobile forms.’ Next, Sirató said, there would be ‘the artistic conquest of four-dimensional space, which to date has been completely art-free’. Salvador Dalí’s Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), completed in 1954, unites a classical portrayal of Christ with an unfolded tesseract. In a 2012 lecture given at the Dalí Museum, geometer Thomas Banchoff, who advised Dalí on mathematical issues connected with his paintings, explained how the artist was trying to use ‘something from a three-dimensional world and take it beyond … The exercise of the whole thing was to do two perspectives at once – two superimposed crosses.’ Dalí, like the nineteenth-century scientists who tried to rationalise spiritualism in terms of existence in some higher space, used the idea of the fourth dimension to connect the religious with the physical.

Twenty-first-century physicists have a new reason to be interested in higher dimensions: string theories. In these, subatomic particles, such as electrons and quarks, are treated as being not point-like, but one-dimensional vibrating ‘strings’. One of the strangest aspects of string theories is that, in order to be mathematically consistent, they require that the space and time in which we live have extra dimensions. A version called superstring theory requires a total of 10 dimensions, and an extension of this, known as M-theory, involves 11, while another scheme, by the name of bosonic string theory, demands 26. All of these additional dimensions are said to be ‘compactified’, meaning that they’re significant only on a fantastically small scale. Maybe someday we’ll learn how to amplify or uncurl these dimensions or observe them as they actually are. But, for now and the foreseeable future, we’re stuck with our familiar three macroscopic dimensions of space. So, the question remains: is there any way we can visualise, in our minds, what a four-dimensional object is really like?

Our visual experience of the world comes about from light entering our eyes, striking our retinas, and creating two flat images. The light-sensitive cells in the retina generate electrical signals, which travel to the visual cortex in the brain where a 3D reconstruction takes place based on essentially 2D information. Having two eyes means that we can see objects from two slightly different angles and the brain learns, when we’re young, to interpret these as differences in perspective and, from them, build a three-dimensional view. But even with one eye closed, we don’t suddenly switch to interpreting things as if they were in 2D. Enough clues from perspective, illumination, and shading still arrive via monocular vision to enable us to add depth in our mind’s eye. In addition, we can move around or rotate our head to change the angle of sight and add to this other sensory data, such as hearing and touch, to flesh out the 3D impression. We’re so adept at adding a dimension in this way that when we watch a movie on a TV screen we automatically inject depth, even without the aid of 3D technology.

The question is, if we have the ability to build 3D pictures from 2D input, could we use 3D visual input to create an impression in our minds of the fourth dimension? Our natural retinas are flat, but electronic technology doesn’t have such a limitation. By using enough cameras or other image gathering devices, stationed in different places, we can collect information from as many directions and perspectives as we like. This alone, however, wouldn’t be enough to form the basis of a 4D view. A genuine four-dimensional observer looking at something in our world would be able to see everything inside a thing simultaneously, in addition to its three-dimensional surface. So, for example, if you had some valuable items locked up in a safe, a 4D being would see not only all sides of the safe at a single glance but everything inside it as well (and would be able to reach in and take those things if it so chose!). This isn’t because the being would have something like X-ray vision that allowed it to see through the walls of the safe, but simply because it had access to an extra dimension. We would similarly have a privileged view of an enclosed space in a 2D world. Draw a square on a piece of paper, to represent a two-dimensional safe, with some items of jewellery inside it. A Flatlander, embedded in the 2D surface, could see only a view of the outside of his safe – a mere line. We, looking from above the sheet of paper that was his world, would be able to see the lines that formed the walls of the safe and all its contents at a single glance and could reach in and lift out the 2D pieces of jewellery. It would mystify the Flatlander how the inside of the safe could be observed, or its contents removed, with no gaps in its walls. But, in the same way, an observer from the vantage point of a fourth dimension would be able to see all parts, inside and out, of something in 3D, whether it was a house, a machine, or a human body.

A way to create the illusion of 4D vision, then, if not 4D vision itself, would be to have a 3D retina, consisting of many layers, each layer of which could hold the image of a unique cross section of a 3D object. The information from this artificial retina would then be fed directly to a person’s brain in such a way that they would have simultaneous access to all of the cross sections, exactly as a true four-dimensional observer would have. The result would not be an actual 4D image but something like the view we would have of a 3D thing if we could look ‘down’ on it from a fourth dimension, which could have some very valuable applications. The first part of the technology required – the 3D retina – is effectively already available in the form of medical scanners that build up a solid picture of part of the human body from 2D slices. The second part is at present beyond us, because we don’t yet have sufficiently advanced brain-computer interfaces or the neurological knowledge needed to feed into the visual cortex so that the brain can construct an all-perspective, all-at-once image of the thing being observed. However, the dawn of ‘Human 2.0’ may be only a decade or two away. Futurist Ray Kurzweil believes that by the 2030s we’ll be enhancing our brains with nanobots, tiny robotic implants that connect to cloud-based computer networks. In 2017, technology entrepreneur Elon Musk launched Neuralink, a venture to merge the human brain with AI through cortical implants.

As well as putting the technology in place and making the right connections to the brain, to see using a 3D retina a person would presumably have to go through a lengthy process of learning how to create mental pictures in this radically new way. However, such an ability could prove invaluable to those involved in areas such as medical diagnosis, surgery, scientific research, and education.

The more difficult step of enabling a person to experience seeing a thing in four dimensions could only be done with simulations, since 4D objects don’t physically exist in our world. Perhaps a computer simulation of a tesseract – the object used by Hinton – would be the simplest place to start. When we look at a 3D model of a tesseract we see only one aspect, or projection, of the true four-dimensional shape. To grasp the thing in all its 4D glory would involve combining multiple projections, seamlessly and simultaneously, in the visual processing parts of our brain. Again, even with all the necessary technology and neural connections in place, it might take a period of training and practice to get the desired effect – to make the fourth dimension, as it were, pop out. But there’s no reason in principle that it shouldn’t work. By mentally fusing, with the aid of computer technology, a large number of 3D sections of a 4D shape, we can hope to know what it is like to see in 4D.

Mathematics allows us to explore, in depth, what our imaginations alone can’t penetrate. It takes us beyond the three dimensions that come naturally to us, so that we can know, in great detail, the properties of things in 4D and beyond. That allows us to push on with the science we need to do to understand the universe at both the submicroscopic and cosmic levels. But more, it opens up the possibility of developing the means to visualise for ourselves dimensions beyond the third.