For the better part of four decades, the National Hockey League consisted of six geographically tight teams: Toronto, Montreal, Boston, New York, Detroit, and Chicago. Teams and fans could hop on a train or bus and travel easily between each city to see games played by the Original Six. The expansion of 1967, which added teams from Philadelphia, Pittsburg, St. Louis, Minneapolis/St. Paul, Oakland, and Los Angeles to the roster, turned the NHL into a continent-wide league with extensive air travel.

Each of the new teams paid a two-million-dollar entry fee to join the NHL in 1967, and the League expanded again in 1969, when, bowing to extensive pressure from Canadian interests, they added Vancouver and Buffalo. In 1972, Atlanta and Long Island were added. The birth of the rival World Hockey Association in 1972 also changed the rules of the game, as competition for players and officials took place. The World Hockey Association, and the expansion of the NHL, changed forever the complexion of the game of hockey, and I was fortunate to have a rink-side seat through those tumultuous years.

The Original Six teams were made up of about 120 players, six goalies, six coaches, three or four referees, and six or seven linesmen. It was a tough lineup to crack, and suddenly, overnight, everything doubled in size. Minor league players came up to join the six new expansion babies and they needed more referees. Hurray!

NHL president Clarence Campbell, when asked if the new product was watered down, said it was just like good whisky, with a little more ice in the glass.

Official sale prices (U.S.) of NHL teams since 2003 include Nashville, which was bought in 2007 for $193 million, and Vancouver, also bought in 2007 for $212.5 million. Forbes Magazine values the Toronto Maple Leafs at $448 million. You can see why there were flocks of lawyers gathered around the potential sale and relocation of the Phoenix franchise to Hamilton, Ontario.

1967 Expansion team Minnesota North Stars Stanley Cup.

Minnesota North Stars

Having apprenticed for three years in the minors, I returned to the big leagues, but not triumphantly. My first game in Minnesota saw one of the coaches throw a bundle of sticks on the ice to express his displeasure. Frank Udvari, my mentor and now one of my supervisors, decided I needed some seasoning — in the press box — and I joined him at a game in Pittsburg the next night, where he explained the intricacies of the art of refereeing a game to me.

I had refereed two NHL games in 1966, the year prior to NHL expansion, and my first game back that year as a referee in Chicago was a thrill. Bobby Hull whacked me on the ass, saying it was good to see me back, and even my old nemesis, Stan Mikita, wished me the best. That soon changed once I fingered Stan for a penalty!

The honeymoon was over shortly — the Rangers beat the Hawks 3–0, and everything was back to normal. After the game, I recall running into my old pal from Sudbury, Rangers goalie Eddie Giacomin, at a dingy basement watering hole, The Western Bar. We toasted my first game as referee and his shutout. I’m sure Chicago coach Billy Reay would have had cardiac arrest if he had run into us.

Speaking of Billy Reay, one year in the mid-seventies, the Black Hawks had won their first three games of the season and were in first place in their division. Then they went on a road trip out West to Vancouver, Oakland, and Los Angeles — and guess who their referee for all three games was? They lost all three games, and, to compound matters, I was on my way to my home base for a couple of days off when the referee scheduled for the next Chicago home game got injured. Yup, I got the call to do the game; the Hawks lost again, and were now in last place. Of course, it was “all my fault.” In those days, in the old Chicago Stadium, both the teams’ and the referees’ dressing rooms were in the basement, right next to each other, and I had to follow the Black Hawks team off the ice and down a flight of stairs to get to my dressing room. The “kindly” old coach blocked my exit from the ice and informed me that I was the worst referee in the history of the League! I replied that he was not exactly in the running for the coach of the week award himself, and we darn near came to blows as we stumbled down the steps to our dressing rooms.

I actually enjoyed Billy Reay and thought he was a good coach. Dennis Hull, who played for the Hawks for thirteen years, told me recently that Billy was a fine man and he had liked him as a coach.

I refereed twenty-five games in the NHL during its first year of expansion and culminated the season by disallowing a tying goal by the Los Angeles Kings, which would have given them first place in the Western Division. The Kings’ owner, Jack Kent Cooke, said he was bilked out of first place by a greenhorn official, but it was a gutsy call, and I was dead right (again). League president Clarence Campbell subsequently issued a press release saying I had made the right call.

It did not take me too long to realize that most coaches, GMs, and owners tried to intimidate the referees — and the referee’s creed should be, “No one takes advantage of you without your permission.” You really have to believe you are the only sane person in the building, otherwise the job will drive you nuts — and some nights it nearly did. You tried not to take the games home with you, difficult as it was not to.

Expansion not only brought in new players and officials, it brought in new owners, and suddenly they became big men around town and got smart in a hurry! Guys who had never had a pair of skates on were suddenly our bosses. Ed Snider in Philadelphia was one of our biggest critics and detractors. He had a thing for referee Bruce Hood (see chapter eight.)

One night in 1975 at the Stadium, I allowed a controversial goal on the Black Hawks, and one of their big defencemen, Bill White, put a headlock on me — literally. I ejected him from the game and after much furor was trying to restart the game. Then my old pal Stan Mikita, who was a darling of the Hawks fans, stood at centre ice and called me every name in the book. He told me I did not have the guts to eject him, but I did. Then I also tossed the Hawks’ Dick Redmond out of the game — for a trifecta! I recall after the game we had about six undercover Chicago police officers swarming around our dressing room, and they drove us back to our hotel, as a fan had phoned in a death threat on me. It was just another night at the office; we thought it was great, because we saved on cab fare!

At first, the League dawdled around and did not take any further disciplinary action against White for the headlock. I remember telling my mentor (and at this point, my boss), Frank Udvari, that if White were not disciplined prior to my next game three nights later in Pittsburgh, my sore neck was going into spasm and I was going to call my doctor and my lawyer, and not necessarily in that order! Frank called me in my hotel room in Pittsburgh the afternoon of the next game, informing me that White had been suspended for five games. I met Frank for a coffee and then we left for the rink.

I feel I had a fairly good relationship with most of the players. I think this was because I had four years as a linesman, where I gained some credibility, and then went down to the minors before returning to the big leagues as a referee. If the players felt you were giving 100 percent they would accept your decision, and if you had that acceptability, you generally hung around for a few years.

However, it wasn’t all work. In October of 1972, I was scheduled to referee a double header on both Wednesday and Saturday in Oakland, when baseball’s World Series bumped us. The Cincinnati Reds checked into our hotel, and all three officials — Will Norris, Ray Scapinello, and I — had to hang around Oakland (and San Francisco) for five days for the rescheduled hockey game that was to be played on the following Sunday. We managed to bum our way into the three ball games, and I told our boss, referee-in-chief Scotty Morrison, that we would be up for the hockey game, but I’m not sure he really believed me. We did quite a lot of touring on our off-day — Will Norris was our tour guide. He would organize our day trips to Napa Valley and so on. It was one of the benefits of the job. I’m sure I have been in more provincial legislatures and U.S. state capital buildings than most politicians.

The noise was deafening during a game early in the 1975–76 season. Madison Square Garden in New York was in a tizzie. Ed Giacomin, the nine-year veteran and all-star Rangers goalie, who had won the Vezina trophy as the best goalie in the NHL and had led the team to the Stanley Cup finals a few years earlier, had been unceremoniously placed on waivers and was picked up by the Detroit Red Wings. And here he was the next night playing goal in a Red Wing sweater against the Rangers, in New York.

All through the National Anthem the Rangers crowd was cheering his name, with the chant, “Eddie-Eddie-Eddie,” reverberating around the Gardens. They really loved the guy! It took a long time to get the game going. Eddie had tears in his eyes and so did I. I called him a big Italian crybaby, and we both laughed. We finally got the game going, and to compound matters, Eddie beat his old team, the Rangers, that night. It was the most emotional scene I have ever witnessed in a hockey game.

Actually, I found the Ranger fans to be very fair, even to the referees. The New York Islanders were also a fair team to deal with. Their coach, Al Arbour, another Sudbury product (it must have been the clean air), kept the players in line, although one night he informed a new referee, Richard Trottier, that he was the worst referee in the League. Linesman Ray Scapinello said, “What about Wicks?” Al rephrased it to say that Trottier was the second-worst referee in the League.

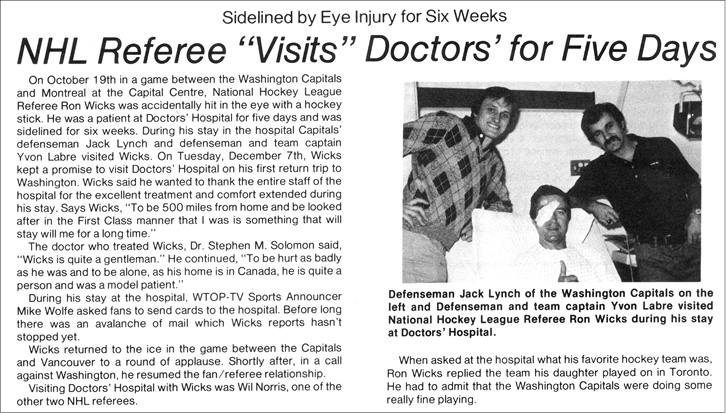

It was a quiet, uneventful game in December of 1976 in Washington DC, when two players came together, and big Harvey Bennett’s stick inadvertently slapped me square in the eye. I was blinded, and I recall vividly that everything turned white in my right eye. I was rushed by ambulance to Doctors Hospital in nearby Maryland, where I spent six days flat on my back in bed. The injury was diagnosed as a hyphema: a blunt injury that with proper rest and care would generally heal fairly well, and fortunately it did. The only after-effect I really have is that my pupil is dilated and I must wear sunglasses to keep the sun’s rays out of the eye. When people asked how my vision was after I returned to refereeing, I used to say “not bad for a referee,” but believe me, it was no joking matter at the time. I was scared!

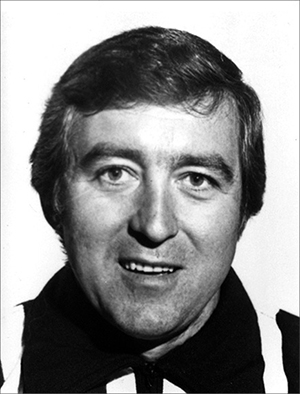

Ron, 1975.

Hockey Hall of Fame

What really impressed me was the warmth of the clubs and the fans. The same people who had been on the referee’s case came to his rescue. Several players from the Capitals, Yvon Labre, and Jack Lynch, came to visit me at the hospital. I received dozens of get-well cards from friends and fans. My wife and my daughter, Lisa, did up a scrapbook of them. I had decided not to call Barb about my injury until the next morning and when I did, she informed me that she knew all about it and that I should be okay and back working in a couple of months. My local Brampton eye doctor, Dr. Dave Dickson, had heard on the early news that I had been injured and he had called her to assure her I should be okay. Thanks, Doc.

Ron in hospital with an eye injury, 1976.

Author’s Collection

On February 1, 1977, I donned a helmet with a visor and returned to refereeing. However, the visor had a little flaw in the centre of it, and when I moved my head quickly to follow the puck I could see two pucks. I was watching a close play at the net and I saw two pucks, one puck in the net and one puck not in the net! I elected to shed the helmet and visor and refereed for another ten years, fortunately without another serious injury.

The World Hockey Association was launched in 1972.9 At first the NHL did not take the new upstart League very seriously and figured it would not last. But it did, and it revolutionized the game. European players were brought in to complement the team lineups. Bobby Hull jumped from the NHL Chicago Black Hawks to the Winnipeg Jets of the WHA, thereby giving the new League instant credibility. The Jets brought two great players from Sweden — Anders Hedberg and Ulf Neilson — to join Bobby Hull, and they were a terrific threesome. Numerous NHL star players left for the new League. Several NHL clubs were ravaged (maybe they were just cheap!), including the Leafs and the Bruins. The Leafs lost Jim Dorey, Rick Ley, and subsequently Frank Mahovlich and Dave Keon. The Bruins, who had just won the Stanley Cup, lost Gerry Cheevers, Derek Sanderson, and others.10

One player told me that he had been making $37,500 in the NHL in 1971 and was offered $175,000 a year later to jump leagues. That’s five times the money!

Bobby Hull was a great player for the Black Hawks. He changed the face of player compensation when, in 1972, he joined the WHA’s Winnipeg Jets for a million-dollar contract. His move resulted in numerous players’ (and officials’) receiving substantial increases in pay. Each of us today should send him a thank-you card at Christmas with a twenty-dollar bill in it!

The WHA was also looking for referees. My old referee pal Vern Buffey was the director of officials for the new league and came after several of us to jump ship. Bill Friday, who was one of our top guns, doubled his salary from $25,000 per year to $50,000. Bob Sloan and several other officials also left. It was great for all of us. I moved up to fill the breach that a seasoned referee like Bill Friday had left and also ended up with a healthy raise in pay. Actually, I, too, was offered a pretty good contract to join the WHA and took it to the NHL as leverage, which may have helped during contract negotiations. So, thank you, WHA.

I was a spectator in Philadelphia the night of the “scheduled” opening game of the inaugural season of the World Hockey Association in 1972. The Philadelphia Blazers were scheduled to open the season. My old pal Bill Friday was the referee and the game was to be played in an old building that was being converted for hockey. I believe it was the Philadelphia Amphitheatre. Everything was looking great, and I remember they handed out souvenir pink pucks to the fans when they came into the rink. The only problem was they had not really tested out the ice-making facilities. When the Zamboni came out to flood the ice for the pre-game festivities, the Zamboni crashed through the ice — and sank! The ice literally came up around the wheels. The game was eventually cancelled, and both Bill and the Blazers’ new star player, Derek Sanderson, got on the microphone and apologized to the fans. It was not enough, of course, to appease the fans, and out came several hundred pink pucks flying onto the ice. (My granddaughter, Nyah, has one of the few remaining pink pucks in captivity.)

This might have been an ominous sign for the Philadelphia club, as they lasted only seven games and then relocated to Miami as the Screaming Eagles. It was only the start of fun and games in the WHA. The referees ended up with red, white, and blue sweaters. I thought it was great. With new teams springing up all over the continent, a little competition was good for business!

World Hockey Association crest.

A little competition was good for business.

Author’s Collection