The people of the Soviet Union started to play our version of ice hockey around 1946 and adopted The Hockey Handbook, written by eccentric Canadian Lloyd Percival in 1951, as their bible of hockey. Boy, did they pick up the game fast. They were superbly conditioned athletes who, in addition to two on-ice practices a day, played soccer to help with their footwork. In the early 1950s, their hockey “Buddha,” Anatoly Tarasov, led the team to several world championship wins.

On a personal note, I had followed the Penticton Vees when they went to Europe in 1955. They had defeated the Sudbury Wolves for the Allan Cup that year, and then they defeated the Soviets 5–0 in the final game, in Germany, for the World Championship. I vividly recall listening to the game, which reportedly had the biggest radio audience in Canadian history to that date.

In 1956, the Soviets reclaimed the top spot in hockey by winning the Olympic gold medal in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. The battle to see who had the better system was in full swing and still is today.

I first saw the Soviets play in 1959 when they made one of their first excursions to Canada and played the Wolves.32 I also recall a game at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1966, watching a big, blond Russian player, Veniamin Alexandrov. He was the Soviet “Bobby Hull.” I am told the NHL would have loved to have him stay, but it was not until over twenty years later that the floodgates opened from Russia and their players were allowed to come to North America.

Following the famous 1972 Series, Frank Mahovlich mentioned that if you gave the Soviets a football, they would win the Super Bowl in ten years. I might not quarrel with that statement.

Soviet players were not allowed to come to the West until several years later, in 1989, and it was too bad, as we missed out seeing stars like the great goalie Vladislav Tretiak, who always said he would have liked to play with the Montreal Canadiens.

In 1979, apparently, an attempt was made to have a one-year trade put together involving the Soviet goalie, Vladislav Tretiak, coming to play for the Montreal Canadiens, and the Canadiens goalie, Ken Dryden, going to play goal for the Moscow Red Army team. The Russians scuttled the deal, saying that Tretiak, who was an army captain, had to complete his military service. (Methinks the Soviets wanted more money thrown in!)

Kate Smith singing “God Bless America”

at the Phildelphia Spectrum.

Goal Magazine

One of the more interesting games in this series was in early January 1976, when the Red Army played the Philadelphia Flyers, who had just come off winning back-to-back Stanley Cups. Here, we had the Soviets, the perennial World and Olympic winners, and the Flyers, the Stanley Cup Champions, playing each other. “Capitalism against Communism.” (And believe me, around 1976, at the height of the Cold War, that was a big deal!) Bragging rights were on the line.

Of course, the “Broad Street Bullies” were their usual charming hosts. Ed Van Impe, their tough defenceman, wiped out Soviet star Valeri Kharlamov so hard that the Soviet coach pulled the team off the ice and right into their dressing room in the first period saying that their players were being damaged for the Olympics. The game was delayed for about fifteen minutes, and it took high-level meetings among League president Clarence Campbell, tournament organizer Al Eagleson, and the Soviet representatives — with interpreters thrown in — to allow the game, and the “friendship series” involving the two touring Soviet teams, to proceed.

Scuttlebutt was that the NHL people informed the Soviets that they still owed them about $250,000 U.S. for the remainder of the tournament games, and if the Soviets refused to play, they would not get the money. The Soviets huddled and replied they would take the money and fix the damage later — with the understanding that Mr. Van Impe and company would ease up on hitting their players, because the Olympic Games were less than a month away.

The game was hyped all over North America and in the Soviet Union. CBC broadcaster Bob Cole uttered the phrase, “They’re going home,” as the Soviets pulled their team off the ice. Fortunately they came back and finished the game!

Philadelphia coach Fred Shero said the 4–1 victory by his Flyers club cost them the next Stanley Cup (and they were the reigning back-to-back champs), as the Flyers had beaten the best and had no more mountains left to climb.

This game and incident made front-page news in the New York Times, which declared the Flyers’ victory “The triumph of terror over style.”33 It resulted in a major international incident. So much for “friendly games”!

Over the holiday season in 1979, the Soviets played a three-game series, the Challenge Cup, against the NHL in New York City. They split the first two games, and the Soviets won the “rubber match,” 6–0, leaving the West to lick its wounds. The Soviets had earned bragging rights.

We all figured it would come down to Canada vs. the Soviets. Little did we know that a group of U.S. college players led by coach Herb Brooks would defeat the mighty Soviets and ultimately win the Olympic gold medal. U.S. broadcaster Al Michael’s famous line, “Do you believe in miracles?” still resonates in my ears!

Apparently the Soviet club was afraid of returning home after this embarrassing loss.

I was selected as one of the two Canadian referees to work the Canada Cup in 1984. We held our training camp in Montreal in August, and I refereed a game there between the Soviets and Czechoslovakia. I still consider it the toughest game I have ever been involved with. These players genuinely did not like each other!34 They kicked at the puck soccer style, and if an opponent’s leg were in the way, so be it. I had done several games with touring Soviet teams and NHL clubs, but never with two Eastern bloc countries that had a history of hatred for each other.

I really did not bother to get too involved in the fray and let “boys be boys.” I remember a newspaperman asking me what I thought of the proceedings, and I replied, tongue in cheek, “Just another game.”

I flew out West to do a game with the Swedes and then ended up doing a game between the Soviets and the United States, as the Soviets had vetoed the use of another referee and asked for me to referee their game. Because of this, Bryan Trottier hung a “commie lover” tag on me.

Since I was Canadian, I was not allowed to referee games in which Canada was involved, but could do games involving NHL players who were playing for the U.S. team. Bryan Trottier, who had played for Team Canada in the 1982 Series, was a North American Indian. He had a type of dual citizenship and ended up playing for Team U.S.A. in the series. I remember calling a five-minute penalty on him for running a Soviet player into the boards, and when Bryan said I was a “commie lover,” I replied it was better than being a “turncoat.” My American linesman got a chuckle out of that one.

In 1987, the Soviets finally relented and let Canadian NHL referees officiate games involving both Canadian NHL players and Soviet teams. Don Koharski was selected and did a fine job. I was a spectator at that final game in Hamilton when Canada won the series, with Wayne Gretzky and Mario Lemieux combining to score the winning goal. This was probably the most exciting game I have ever witnessed and was as thrilling an event as you could find. In the final game, the Soviets were up 3–0 after eight minutes, and were tied at 5–all in the third period with 1:26 left in the game. Wayne Gretzky broke into the Soviet zone, dropped a lovely pass to Mario Lemieux, who wristed it into the top corner past the Soviet goalie, bringing down the house.

The European invasion of players to North America took place after the historic 1972 Summit Series — not Russians, but primarily Swedes. With the advent of the World Hockey Association in the fall of 1972, the Winnipeg Jets brought in Anders Hedberg and Ulf Nilsson to play with Bobby Hull. In 1973, the Maple Leafs brought over Borje Salming and Inge Hammerstrom, and the floodgates began to open. Peter Stasny defected from Czechoslovakia in 1980, joining the Quebec Nordiques. In my opinion, Stasny was every bit as good a player as Wayne Gretzky, but tougher. His brothers Marion and Anton joined him later in Quebec. Jarri Kurri came from Finland along with numerous others. In fact, without European players there is no way the NHL could have expanded like it did. It was not until 1989–90 that aging Soviet players came to North America. About nine Soviets in total came that year, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

In 1990, the Soviet Oldtimers played an exhibition series against Team Canada Oldtimers, and I had an opportunity to work as a referee alongside my NHL buddies Bill Friday and Bruce Hood. It was a great time. I had never been on the ice with Bill and Bruce, as the League used only one referee in the old days. We started in Hamilton, went to Ottawa, and then to my hometown of Sudbury, which was a thrill, then out to Western Canada.

I remember a Russian player at the game in Ottawa saying that I was a good referee for Canada, implying that I was a “homer.” On the flight west, I tried glasnost and sent him a vase of flowers and a cold beer. By the time the series ended, he had given me his address and invited me to visit him in Moscow. (By then I figured I should join the United Nations.) They were all good guys, and we had a fine time together.

At the end of each of the first periods of the five-game series, we would have a five-man shootout against the Russian goalie Vladislav Tretiak. The Canadians never scored one goal in the twenty-five shots. I observed that prior to the shootout, Vladislav would turn and face the goalpost and hypnotize himself to get into the “zone.” After the last game in Saskatoon, we all had a beer and he confirmed this fact. He told me he had been taught this in Soviet military school as a ten-year-old. Vladislav Tretiak ended up as president of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation, and former Russian star Vyacheslav “Slava” Fetisov was minister of sports in Russia.

I was not too surprised when I heard that Fetisov was appointed to a senior cabinet position in Russia. I recall sitting in the hotel lobby in St. Louis, years earlier, and noting that when the Soviet coach Viktor Tichonov came out of the elevator, the Russian referee sitting beside me got up and went upstairs to get Viktor’s luggage. (In Europe, the referees were part of the team, and this was part of his duties.) But when Fetisov came out of the elevator, the whole team stood up and caught the bus to the rink. I knew then who was really in charge.

Coach Tichonov was not loved by his players. He imposed military-style discipline on them, and many of them were in the military. (Note the team name, Red Army.) He used to stand in front of his players’ bench and shout at them. He also liked to help the officials make their calls. I remember he did not feel that linesman Ron Finn had made the proper call and Viktor grabbed the linesman’s arm. Finni reacted normally and gave Viktor the gentlest judo chop over his arm that I have seen in years. I had to saddle over and inform Viktor to keep his hands off our NHL officials. One of the Russian players came over later and nodded his head in agreement with our actions.

Sam Pollock, head of Canada’s Olympic Hockey program, said in 1984, “It’s been my experience that if we want to wear our red uniforms, the Russians will decide that was what they had in mind. But if we prefer white, for some reason they’ll insist they can’t possibly wear red.”

The Red Army’s top line of Vladimir Krutov, Igor Larionov, and Sergei Makarov were tops in the sport. Krutov was a little chunky guy, looked like a fire hydrant, and he liked to moan. I called Vladimir a crybaby, and Igor started to laugh. Igor was one of the first Russians to come to North America and he won three Stanley Cups with Detroit. He was a very sophisticated person who, like many others, was held back by the Soviet system where no one individual was allowed to stand out.

There is no hall of fame in Soviet hockey. There has been no pension plan for the players. In many cases, the system, which used the players in their youth, abandoned them when they could no longer play well. Many of the former star players in the old Soviet Union have fallen onto hard times.

Lawrence Martin in his book, The Red Machine, talks about the Soviet hockey education system. According to Martin, their system did not allow for any star players. It was to be a collective game to promote communism. Martin indicates that over 5 million youngsters were put into sports schools. He describes the career of “Slava” Fetisov, who joined the Red Army group at eight years of age and played with their team for ten years.35 He then joined the Soviet National team, winning eight world championships and two Olympic gold medals. He was the team captain and stated publicly that their system created “ice robots.” He put up a six-month fight to leave Russia legally and play in the NHL. (He also came perilously close to being sent to Siberia.) In 1989, at the age of thirty-one, he was allowed to come to North America and ultimately added the Stanley Cup to his resumé.

Lawrence Martin states that fighting was not allowed in Soviet hockey, with suspensions running between three to fifteen games. The Soviets’ penalty leader in the 1970s and 1980s, Vladimir Kovin, totalled 540 minutes over twelve years, an average of less than fifty minutes per season. In one season, Dave Schultz of the Philadelphia Flyers had 472 minutes in penalties, which almost equalled Kovin’s total twelve-year output. Compared to the leading pugilists of the NHL, Kovin was a Lady Byng candidate.

In March of 1989, while playing in the Russian league, Alexander Mogilny of Central Army fought with and beat up a Spartak defenceman, Yuri Yaschin. For this conduct, Mogilny was suspended by the Russians for ten games. Martin comments that he was also stripped of the honour he had won as a gold medal winner in the Olympics in 1988 in Calgary — the merited Master of Sport for the Soviet Union. These severe punishments became contributing factors in Mogilny’s decision to defect to the Buffalo Sabres of the NHL in 1989, Martin concludes.

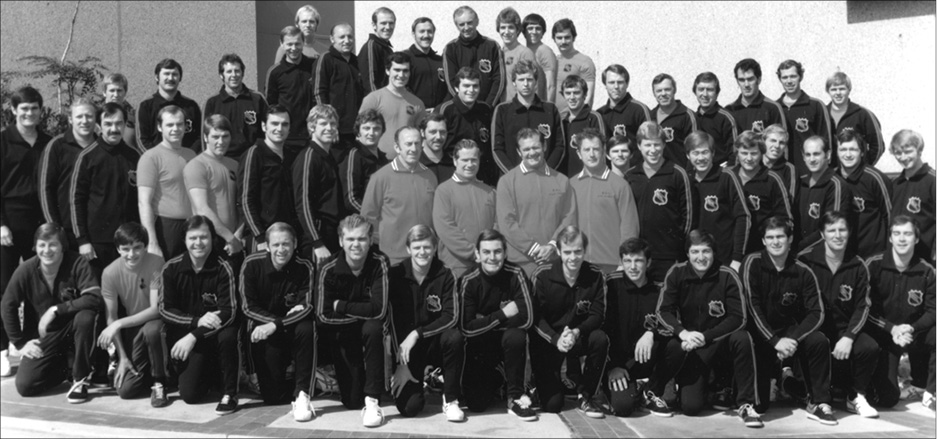

NHL Referees Training Camp, mid-1970s.

National Hockey League

Around the mid-1970s, the NHL invited three Soviet referees to our referee training camp in Toronto. I drove them to and from the rink each day and we became chummy. However, I noticed that when we were all together, none of them spoke English. When I was alone with one of them, they asked me numerous questions about the cost of cars, salaries, etc. We had a barbeque at my house and we played Roger Doucet’s record, Songs of Glory. When he belted out the Soviet National Anthem in Russian, they all said in unison, in English, “better than the Soviet tenors.” We all enjoyed the rest of the evening, speaking fluent English with each other!

I felt sorry for the Soviets, inasmuch as they could not trust their system and their colleagues. I am pleased to see that their system has now changed for the better.

32 I was a “rink rat” at the Sudbury Arena at that time and still have a one-piece, hand-carved stick that the Soviets used. They had very little hockey equipment and would trade vodka and caviar for skates and any other equipment they could get their hands on.

33 The Flyers were considered “Hooligans” by the Soviets, who professed to play a clean version of the game.

34 Apparently the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 was still very fresh in the minds of the Czech players. Jaromir Jagr, one of hockey’s premier players, has always worn number sixty-eight on his back in reference to the year the Russians invaded his native Czechoslovakia in 1968.

35 As mentioned earlier, Vyacheslav “Slava” Fetisov was Minister of Sport in President Putin’s Government in Russia, displaying that he had the courage of his convictions!