In October of 1960, with my NHL invitation in hand, I boarded “The Canadian,” the overnight train from Sudbury to Toronto. Upon arrival, we were put up at the ritzy King Edward Hotel for the lofty sum of three dollars and fifty cents per night. The next day, a bunch of new rookies and I drove up to Peterborough, Ontario, where the Toronto Maple Leafs had their training camp. The Leafs were playing the Chicago Black Hawks in a pre-season exhibition game, and several of us trainee linesmen each worked one period of the game with an NHL linesman.3 The referee was Frank Udvari and the linesman was George Hayes.

To say I was nervous and excited would be a classic understatement. Here I was, fresh out of the Sudbury midget league, and now I was doing a big-league game. The stars went out of my eyes quickly when big “Moose” Vasko of the Black Hawks, who weighed about 225 pounds, got into a scrap with Tim Horton, who was the Leafs’ tough guy. Since I weighed about 150 pounds, I had to use my best powers of persuasion to get these combatants to proceed to the penalty box in an orderly fashion.

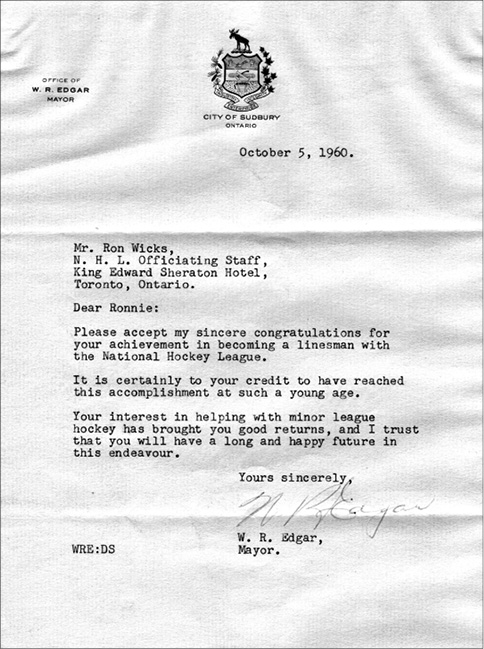

Congratulatory letter from the mayor.

Author’s Collection

Dan Newell and Ron off to the Big Leagues!

Sudbury Star

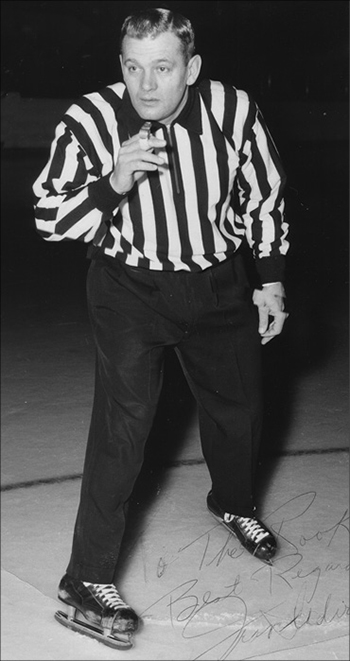

Referee Frank Udvari, my mentor.

Author’s Collection

On October 5, 1960, having just turned twenty years of age, I officiated in my first big-league game. The Boston Bruins, including my pal Jerry Toppazzini, were playing the New York Rangers in New York City. Frank Udvari was the referee, and George Hayes was the other veteran linesman. I was as green as grass, and these veteran officials had lots of fun with the rookie from Sudbury. Yet, they made me feel welcome right off the bat and allowed no one to take advantage of my inexperience. Of course, in the mornings I had to get coffee for both of them (and the New York Times Sports section for big George Hayes, who took me under his wing and showed me the ropes in the big leagues). League president Clarence Campbell was at this opener and said I missed an offside by twenty feet. I must have improved because I lasted for twenty-six seasons!

I signed my first NHL contract for $2,500 for the 1960–61 season. Linesmen were paid forty dollars per game. I officiated in seventy-five regular season games and got the thrill of officiating four games in the Stanley Cup playoffs at seventy-five dollars per game, for a total of $3,300. I was so pumped up to be there that I am sure I would have worked for nothing. When I think back, I just about did.

We used to get twelve dollars per day for expenses back in 1960 and we had to pay for our hotel out of that. We would bunk in together to save a buck; many times as the rookie I got to sleep on the hotel floor on the afternoon of a game.

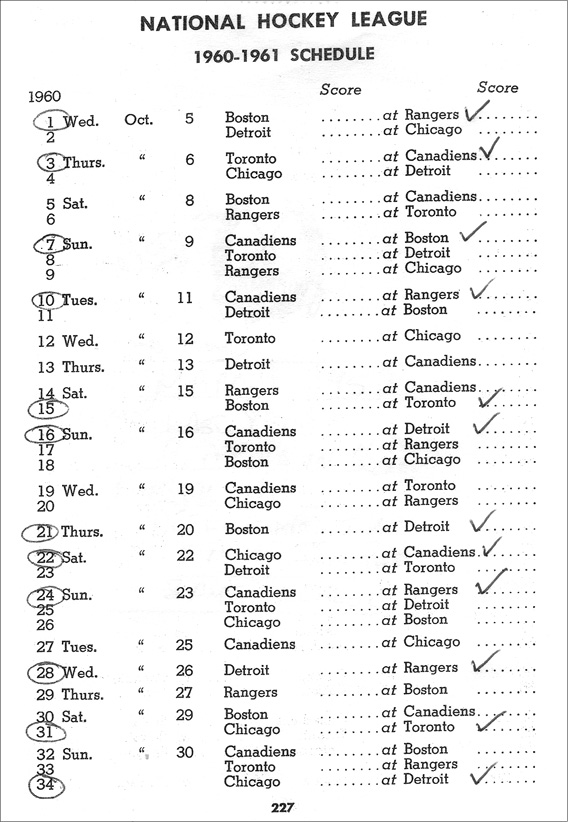

October 1960 schedule, my first month.

National Hockey League

During my first year away from home, I lived with some wonderful people in Toronto, Mr. and Mrs. Walter Newell, whose son, Jack, had refereed with me up north. I commuted to Sudbury on off-days and often also took the overnight train from Sudbury to Montreal. I became a bit of a local celebrity, as the Sudbury TV station would show a Toronto Maple Leafs game one Saturday night and a Montreal Canadiens game the next Saturday. If my schedule was right I would be on TV most Saturday nights in Sudbury. My dad, Charlie, thought it was great; it gave him bragging rights at the local Legion.

One of the highlights of my initial year as a young official was my first experience in the Stanley Cup playoffs in the spring of 1961. I officiated in a semi-final game in the raucous Chicago Stadium, between the Black Hawks and the Montreal Canadiens. The game went into fifty-two minutes of overtime and was won by Chicago, which scored on a power play while Montreal star Dickie Moore was in the penalty box for tripping. Just as the referee, Dalton McArthur, was reporting the winning goal, Montreal coach Hector “Toe” Blake scurried across the ice — in his street shoes — and threw a punch at the referee, striking Dalton on the side of the face. I was flabbergasted! We convened the next morning in Mr. Campbell’s suite at the La Salle Hotel. As officials, we all figured Toe had to be suspended, but he was only fined $2,000 for punching the referee. He was still allowed to coach the next game two nights later at the Stadium. Prior to the next game, referee Eddie Powers informed the Montreal captain that he did not want to hear one word from the Canadiens bench during the ensuing game — and we didn’t.

My first NHL contract and 1960 list of officials — wow!

Author’s Collection / National Hockey League

Montreal had won five consecutive Stanley Cups, but never recovered from this loss. They failed to reach the finals for the first time in eleven years, and the Black Hawks ultimately went on to win the Cup that year — but have not won it since.

In the early 1960s, Toronto’s coach, George “Punch” Imlach, especially when annoyed at an official’s decision, had a quaint habit of calling his team to his bench and stalling the game. During the Stanley Cup playoffs, the officials held pre-game meetings, and at our meeting that morning in Mr. Campbell’s office in Montreal, the League president informed the officiating crew for the evening’s game (referee Vern Buffey, the other linesman, and myself) that if this delay happened again that evening, we were to just drop the puck, even though there were no Maple Leafs players on the ice. We could then put the Leafs club on report, and if this stalling happened once more, we could impose a minor penalty for delay of game.

Retraction article from the “drop the puck” incident.

Sudbury Star

Sure enough, in the game that evening in Montreal following a stoppage of play in the Leafs end, Punch decided to call his team to his bench to try to stall the game. I was standing in the face-off circle with the Montreal captain, Jean Beliveau, when Vern shouted over to drop the puck.4 Being an obedient servant, I did, and Vern immediately blew his whistle. The puck ricocheted off the Leafs goalie Johnny Bower, and the Leafs club came charging back into their own end. Dave Keon, their Lady Byng candidate, had me pinned up against the boards asking me what the hell I was up to by dropping the puck.5

The Montreal press had a field day with this incident and I was chastised by Red Fisher of the Montreal Star. The implication was, if the puck and gone into the net (and we rightfully would have had to disallow it), I, the rookie linesman, would have been on a one-way ticket back to Sudbury — my big-league career tout fini.

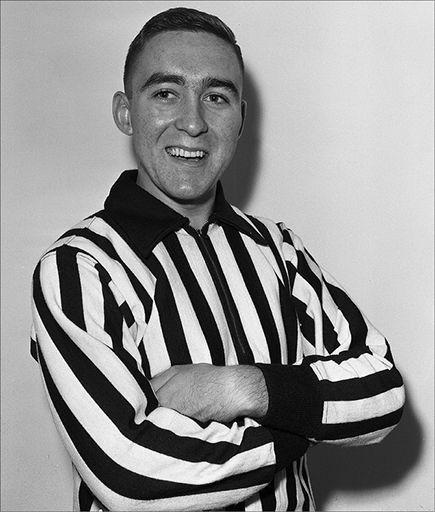

Young Linesman, ca. 1962.

Turofsky, Imperial Oil, Hockey Hall of Fame

The next morning, the officiating crew was summoned to the venerable league president’s office in the Sun Life Building (and I thought this would be the last time I would ever ride up its elevator). When we entered Mr. Campbell’s office, the article in question was sitting on his desk, circled in ink. I thought, “Uh-oh! I’m through!”

Mr. Campbell never said a word to us, just picked up the phone, called the Montreal Star, and got Red Fisher on the line. I clearly recall the discussion during which he informed Mr. Fisher that he had a young man sitting across the desk from him shaking like a leaf. True! He then informed Mr. Fisher that the game officials had made the proper call and were strictly following the orders of the League president. He further stated that if the Montreal Star ever wanted another statement on any issue from the League office, they were to print a retraction and state that it was he, Clarence Campbell, who had instructed the officials to drop the puck in order to galvanize (and he spelled it out) the Leafs club into action!

Whew! I’m sure colour came back into my face. I think I flew down the stairs. Vern took me over to Ben’s restaurant for a smoked meat sandwich, and, since it was a non-game day, I think we even had a beer. Years later we both laughed at the incident, but it wasn’t funny at the time.

In January of 1963, the Montreal Canadiens lost to the Toronto Maple Leafs 6–3 at the Montreal Forum. Coach Toe Blake was not pleased with the officiating and was quoted in a French newspaper as saying that referee Eddie Powers handled the game as if he had a bet on the outcome. This attracted the attention of NHL president Clarence Campbell, who said the matter would be investigated. Later, Blake was fined two hundred dollars by Campbell. Powers, who was the NHL’s senior referee, considered the fine inadequate and submitted his resignation as a referee during the middle of the season.

I worked Eddie’s last game several weeks later in Toronto, and it was a trying time for all game officials. He had contemplated quitting before the game but did not want to place two linesmen — who had never refereed — in the difficult position of having to take over as the game referee.

Incidents of this type highlighted the fact that, as referees, we were subject to serious criticism of our ability and integrity with what we felt was minimal reaction and support from the League. I began to wonder if I really wanted to leave my cozy job on the lines and go into refereeing some day!

On the surface, I think Montreal coach Toe Blake disliked referees and tolerated linesmen. I feel the red armband the referees wore infuriated him — like a matador to a bull. Toe came from Sudbury, and we personally got along well. On one of our New Year’s Eve overnight train trips during my first year in the league, he invited me into his sleeper roomette for a holiday beer and gave me some great advice about dealing with the players. His advice was to be cordial with the players but not too chummy with them. I followed that advice for the rest of my career.

In the early ’60s, most teams and officials travelled by train. Some of the more interesting trips were after a Saturday night game in Montreal. Both teams and the game officials would grab a quick shower and then we would all rush to catch the overnight train, generally to either Boston or New York. Each team had different sleeping cars on the same train, with the officials in another car, but we all had to have breakfast together. Some mornings I expected the fisticuffs to begin at eight a.m., not eight p.m. It livened things up a bit more if the kindly old coaches realized at the train station that they were stuck with the same referee for the Sunday night game. (How the hell did we feel to be stuck with a cranky coach for back-to-back games?) Usually both teams were playing each other the next night, which made for some rollicking times, as the fights would start as soon as the first puck was dropped on the Sunday night.

Saturday night in Toronto provided the same drama. We used to hustle down to catch the 11:15 p.m. train to Chicago. We’d usually have time to stop in for a quick beer and a sandwich “to go” at the Walker House next to the Royal York Hotel, and then head off to Union Station. Pretty heady stuff for a twenty-year-old.

In 1962, after two years on the lines, I had developed fairly well as an official and, as a testament to my work, was awarded the opportunity to work the season-opening NHL all-star game in Toronto. There was an awards dinner the night before at Toronto’s Royal York Hotel. I was there enjoying the festivities when Chicago’s owner, Jim Norris, “bought” The Big “M” — Frank Mahovlich — for one million dollars, from Toronto. Norris gave one of the Maple Leafs owners, Harold Ballard, a deposit on the sale. Apparently the wine was flowing a little too much and the deal was scuttled the next day. The press had a field day with this aborted sale, and I recall it being a big point of discussion during the all-star game being played the following day.

Interesting that Chicago had offered the Maple Leafs a million dollars cash for Mahovlich, and Frank and his agent (his dad, Peter) were haggling with the Toronto GM, Punch Imlach, for a five-hundred-dollar raise. This incident further widened the gap between Imlach and Mahovlich and other star players on the Leafs.6

The next day, at the all-star game, Matt Pavelich and I worked as linesmen. While standing at centre ice before the game, I realized we were the only two guys on the ice who were not benefiting from any NHL pension plan contributions that came from the game. All the players and the referees were in the pension plan, but not the linesmen. On our next trip into Montreal, Matt and I met with league president, Clarence Campbell, and he got us into the plan retroactive to the start of the 1962–63 season. This was only the first — but not the last — time I realized that we had to keep an eye out for our pension benefits. (Apparently, twenty-five cents from each all-star ticket was to go into the NHL Pension plan to enhance the players’ and referees’ pensions, but it turned out this amount was applied to reduce the owners’ administration cost.)

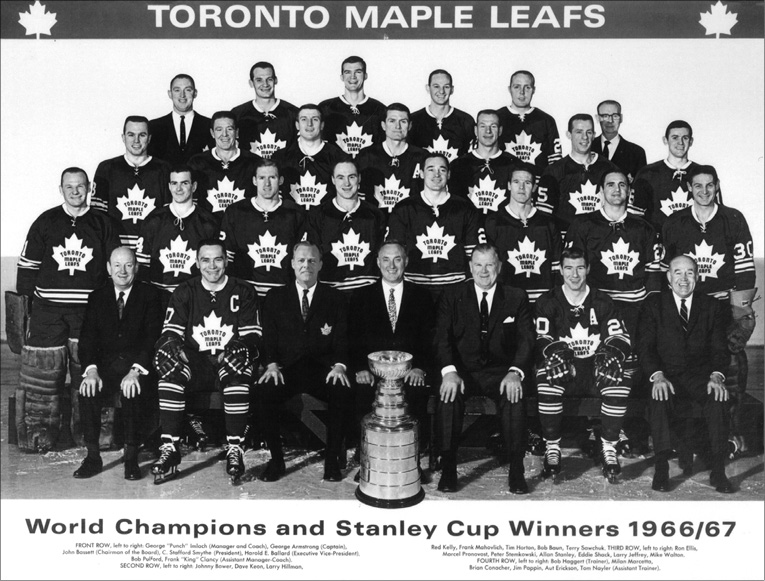

Toronto was a great hockey town in the early ’60s. The Leafs won the Stanley Cup in 1962, 1963, 1964, and 1967. Frank Mahovlich, Dave Keon, and Al Stanley were big parts of those teams. Ironically, some of my earliest heroes came from Northern Ontario. At one point I really believed that all Stanley Cup-winning goals were scored by Northern Ontario players. I worked the lines in the ’60–’64 era, and it was exciting to be part of the proceedings, even though I was an impartial observer.

Frank Mahovlich was a great talent and one of the best players to play the game. Dave Keon was pound-for-pound probably the best player to wear a Toronto Maple Leafs uniform. He was a skating wizard. Mahovlich and Keon are rated as two of the top five greatest Maple Leafs players, and with good reason. Both had some differences with the Club over the years but were great competitors.

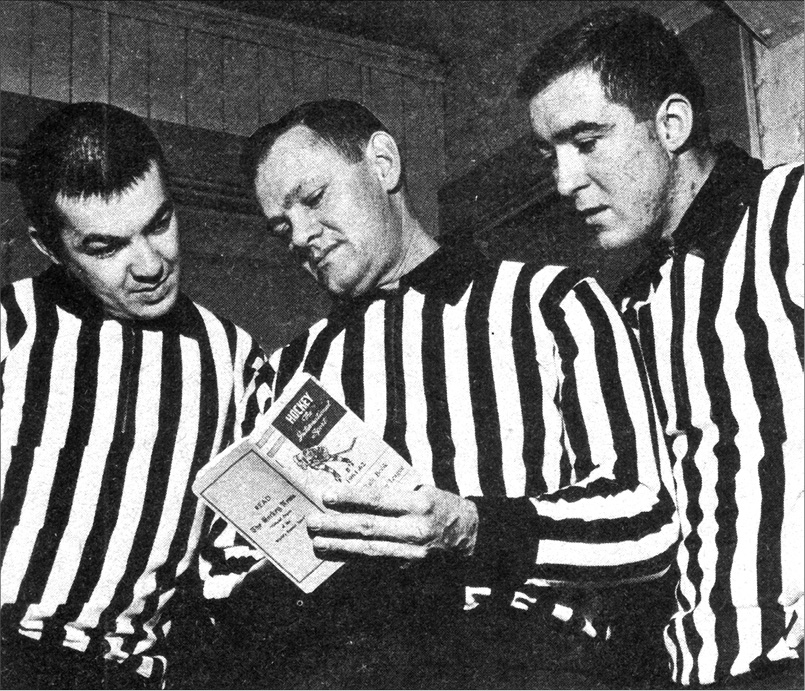

Matt Pavelich, Frank Udvari, and Ron reading the rule book.

Hockey Pictorial Magazine

I recently watched a Leafs classic replay of the 1963 Finals, where Toronto beat Detroit, in the fifth game in Toronto, to win the Stanley Cup. I had worked the game as a brush-cut linesman, and the rekindled memories of this game took me back over forty years. The best part was watching Detroit’s Gordie Howe and Toronto’s Johnny Bower embracing after the game and discussing how they were going to go fishing together in Saskatchewan as soon as they could.

I remember being on the lines in the 1964 Stanley Cup finals, when Bobby Baun of the Leafs was removed from the ice in the third period on a stretcher to the infirmary, where it was determined that he had a broken ankle. Baun had the ankle frozen and put his foot back into his skate. He then came back and scored the game-winning goal in overtime. It went down as one of the highlights of the game of hockey. They made them tough in the Old Days.

The Toronto Maple Leafs, 1967 Stanley Cup winners.

Hockey Hall of Fame

3 The Chicago Black Hawks’ name was changed a few years ago to Blackhawks.

4 Linesmen could drop the puck at the request of the referee, or in the last minute of play in a period.

5 The Lady Byng Memorial Trophy is an annual award given to the player adjudged to have exhibited the best type of sportsmanship and gentlemanly conduct combined with a high standard of playing ability.

6 Punch used to pronounce Frank’s name as Maholovich, just to upset him, and it did. He demanded to be traded away from the Leafs, was traded to Detroit, and eventually ended up with Montreal. Frank was a great talent who was underutilized by the Maple Leafs. In 1998, Frank was appointed to the Canadian Senate.