Chapter One

VISIONS OF AQUARIUS

THE CREATION OF THE 1969 WOODSTOCK MUSIC AND ARTS FAIR

“For most of America’s youth of the 1960s, the search for personal identity that varied from the traditional values and aspirations of our parents was the priority of the day,” recalls Don Aters, famed rock music photographer and historian from New Albany, Indiana.

Don Aters in high school.

“The sixties saw the golden age of rock and roll, the advent of psychedelica, and the turmoil of the most violent times in American history. The migration to Woodstock was a gathering of ‘Rainbow Warriors.’ We were communal, culturally diverse, and in search of universal peace through the music that defined our generation. With Vietnam raging and shown daily on television as well as the front page of every newspaper, it seemed to us that cultural acceptance was imminent, and that music would be the universal elixir.”

Following his discharge from the military, the sights and sounds of the West Coast and the allure of “hippiedom” seemed more viable to Aters than the death and destruction in Southeast Asia. “I was 21 years old, and earlier that year I was indirectly implicated in a civil rights riot in downtown Louisville, Kentucky. I was struck in the face with a heavy pipe, spent 14 days in a coma, and given a poor prognosis for full recovery. A few months later I was on the Pennsylvania Turnpike to join the assumed 25,000 participants expected at the Woodstock Music & Arts Festival. The lengthy sojourn seemed more of an excursion to a tropical rain forest, and when we arrived, the burgeoning crowd was overflowing from Yasgur’s farm. We—nearly 500,000 ‘flower children’—became a beacon in a sea of despair for a world that seemed at odds with everything, including peace and love. During those few days in August of ’69, the youth of America brought the world to its knees in a humbling display of confusion as to how a gathering of this magnitude could exist without any of the typical confrontations expected from the ‘mainstream.’

Arnold Skolnick’s classic Woodstock poster.

The migration to Woodstock was a gathering of ‘Rainbow Warriors.’ We were communal, culturally diverse, and in search of universal peace through the music that defined our generation.

“Critics of the counterculture, the cultural revolution, the inhabitants of Haight-Ashbury, and those who attended this historical event are also those who adopted the phrase, ‘Take nothing but memories, leave nothing but footprints.’ For those of us who experienced those damp and cloudy days long ago, we represent the majority of today’s population, and we remain as a community of collective souls who embrace our past and look towards the future.”

As in all events, it is the media that holds the power to shape how history is remembered and perceived—making more out of what was less, and, conversely, making less out of what was more. Nowhere is this truer than with Woodstock. In researching Woodstock, Peace, Music and Memories, a consistent theme emerged from those who recollected a time in their youth some 40 years ago: pride in the accomplishments of a generation of displaced youth, briefly showing the world how things could be if they were in charge. And a disappointment in how the media, charged with a mission to reduce the event to “reckless sex, drugs, and rock ’n roll,” irresponsible hedonism, held Woodstock as proof against a youth culture that was questioning authority and threatening the conservative status quo. A symbol of 1960s excess. Unfortunately, as do many historic victims of the media, Woodstock, too, has maintained its well-spun misperception as something more infamous than significant.

As those once youthful witnessess to this event become the more senior members of our culture, it’s time to set the record straight.

“For all those naysayers who know little about what we represented so long ago, we are the Woodstock generation,” says Aters. “The memories remain, as do most of us, and so do our ideals. Now 40 years later, a toast to the most sensational event in the annals of contemporary history, a toast to those who orchestrated the Herculean festival, and most of all, ‘cheers’ to all of us. May we forever be the torchbearers for universal acceptance. Rock in peace!”

Take nothing but memories, leave nothing but footprints

— Chief Seattle

Woodstock at its height.

A generation brought together.

The Band.

On a shortlist of historical events, Woodstock has remained part of the cultural lexicon. As Arnold Skolnick, the artist who designed Woodstock’s dove-and-guitar symbol, described: “Something was tapped, a nerve, in this country, and everybody just came.”

From Aug. 15 -17,1969, the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair held in the Catskill Mountains of New York’s Sullivan County, on Max Yasgur’s farm in the town of Bethel, was mecca to an A-list of the top performers of rock, folk, and popular music of the time. The rural Borscht Belt area, best known for farming and summer vacationing, would be transformed overnight, briefly becoming New York State’s second largest city of more than 450,000 people.

Costing more than $2.4 million, Woodstock was sponsored by four very different and very young men: John Roberts, Joel Rosenman, Artie Kornfeld, and Michael Lang. Twenty-four-year-old John Roberts was heir to a drugstore and toothpaste manufacturing fortune and supplied the money. Roberts’ slightly hipper friend, Joel Rosenman, 26, was the son of a prominent Long Island orthodontist and had just graduated from Yale Law School. Roberts and Rosenman met on a golf course in the fall of ’66, and by the winter of 1967, they shared an apartment, contemplating their future. Their thought and hope was to create a screwball situation comedy for television, a male version of “I Love Lucy.” To get plot ideas for the sitcom, Roberts and Rosenman put a classified ad in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times in March 1968: “Young Men with Unlimited Capital looking for interesting, legitimate investment opportunities and business propositions.”

Carlos Santana.

Artie Kornfeld, 25, was already well established in the music business. He was Capitol Record’s first vice president of rock music, and was the company’s connection to the rockers whose music was starting to sell millions of records.

Michael Lang, 24, was described by friends as a cosmic pixie with a head full of curly black hair that bounced to his shoulders and who rarely wore shoes. In 1968, Lang had produced the two-day Miami Pop Festival, which drew 40,000 people. Later that same year, Lang was managing a rock band and wanted to sign a record deal, so he brought his proposal to Kornfeld at Capitol Records in December. Lang knew that he and Artie had both grown up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, and used that as his edge, telling the company’s receptionist that he was “from the neighborhood.”

Woodstock co-creator and promoter Kornfeld remembers: “One day, my secretary buzzed me to say, ‘Mike Lang is here to see you.’ I asked if he had an appointment and she answered, ‘No, he doesn’t, but he said to tell you he’s from Bensonhurst.’ With guys from the neighborhood, you let them in! Michael had all this hair sticking out and I was pretty straight, and to me, he looked like the ‘king of the hippies.’ He had this terrible band called ‘The Train’ and he wanted me to get them a development deal with Capitol. To make a long story short, we took them into the studio and the session was a disaster. Whether we were drinking too much red wine or whatever, the only thing that came out of that was the beginnings of our friendship.

“Over time, Michael ended up staying at my place with me and my wife, Linda, and we’d spend nights talking and rambling until morning. One night, we were playing bumper pool, smoking some great Columbian, and Michael started teasing that I didn’t go to clubs anymore to see live acts; truth being, after 12 years in the music business I’d become too busy. That’s when I said, ‘Michael, I have a great idea. What if we had all the money in the world—we could rent a Broadway theater, have a concert, and just invite our friends. We could get Jimi Hendrix, The Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater, Sly Stone, The Beatles, and every other act that we would love to see perform. We won’t charge anything, and it will be one of the greatest parties of all time.’ I thought I’d finally get to see all these acts, and Michael thought we should host our festival in Woodstock, New York. Michael also dreamt of a recording studio in Woodstock. It was a popular artist’s colony. People like Paul Butterfield, Bob Dylan, The Band, and Richie Havens were also living there, and it had really become the ‘in’ place. We talked endlessly about putting on this show and hoped that maybe 100,000 people would show up, or at least 50,000. My wife, Linda, thought maybe half a million because those love-ins were getting 10,000 people, and if we had all those acts…. I would say we dreamt about this for months and figured it would stay just that—a dream.”

Kornfeld continues: “One day Michael’s lawyer called to tell us that there were two guys [John Robert and Joel Rosenman] advertising in the New York Times, who had unlimited capitol for investment, and he convinced me to get in touch with them. We pitched the idea for the recording studio in Woodstock, and John and Joel saw the opportunity to finance it through our idea of a music festival. We got backing for our dream, and the deal was sealed.”

The four met in February 1969, and by the end of their third meeting, the little party had snowballed into a bucolic concert for 50,000, the world’s largest rock and roll show ever, and the four partners formed Woodstock Ventures Inc., named after the hip little Ulster County town.

The team found a site owned by Howard Mills Jr., and for $10,000, Woodstock Ventures leased a tract of land in the town of Wallkill.

“We drove up to Wallkill and saw the property,” Rosenman says. “We talked to Howard Mills and made a deal. The vibes weren’t right there. It was an industrial park,” but Roberts insisted that they needed a site immediately. The 300-acre Mills Industrial Park offered perfect access. It was less than a mile from Route 17, which linked to major thoroughfares, and it had the needed essentials like electricity and water lines. In late March or early April, Rosenman told Wallkill officials the concert would feature jazz bands and folk singers. He also said that 50,000 people would attend, if they were lucky.

In the cultural-political atmosphere of 1969, promoters Kornfeld and Lang knew it was important to pitch Woodstock in a way that would appeal to their peers’ sense of independence. Lang wanted to call the festival an “Aquarian Exposition,” capitalizing on the zodiacal reference from the musical “Hair,” and he had an ornate poster designed featuring the Water Bearer. By early April, the promoters were carefully cultivating the Woodstock image in the underground press, in publications such as the Village Voice and Rolling Stone magazine. Ads began to run in the New York Times and the Middleton, New York Times Herald-Record in May. For Kornfeld, Woodstock wasn’t a matter of building stages, signing acts or even selling tickets; for him, the festival was a state of mind, a happening that would exemplify the generation. The event’s publicity shrewdly appropriated the counterculture’s symbols and catch phrases. “The cool PR image was intentional,” he said.

Advertising coupon for Woodstock.

The group settled on the concrete slogan of “Three Days of Peace and Music” and downplayed the highly conceptual theme of Aquarius. The promoters figured peace would link the antiwar sentiment to the rock concert, and also wanting to avoid any violence, they thought a slogan with peace in it would help keep order.

The Woodstock dove is really a catbird. “I was staying on Shelter Island off Long Island, and I was drawing catbirds all the time,” said artist Arnold Skolnick. “As soon as Ira Arnold [a copywriter on the project] called with the copy-approved ‘Three Days of Peace and Music,’ I just took the razor blade and cut that catbird out of the sketchpad I was using. First, it sat on a flute. I was listening to jazz at the time, and I guess that’s why. But anyway, it sat on a flute for a day, and I finally ended up putting it on a guitar.”

Kornfeld adds, “With John and Joel’s initial investment, I had a small budget for advertising, and I couldn’t imagine that it was just hippies in the Village in New York City who had no money, who would be into this. They wouldn’t be able to come up with $8 for a ticket for each day of the festival. I took an ad out in the New York Times, the Village Other, and the Village Voice with a coupon that they had to fill out for more information. When those coupons started coming in, I thought, ‘Wow, 89 percent of these kids are white, middle-class, college types.’ With the money I had left, I went to the radio stations, and with my promotion skills, advertised directly to reach those kids. I researched, so I knew when they would be on the beach or in their car listening, and I used airplanes to pull banners advertising the event. That ad, which first ran on my wedding anniversary, ended up bringing in a million and half dollars to get this thing up and running.”

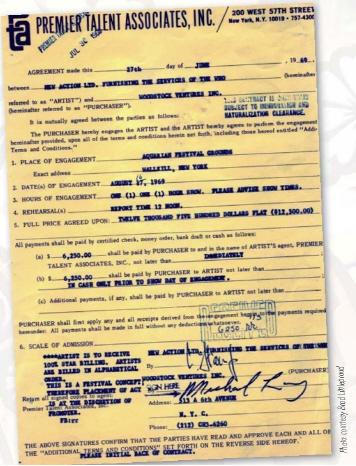

Woodstock Ventures was aiming to book the biggest rock and roll bands in America, but the rockers were reluctant to sign with an untested outfit that might be unable to deliver.

“To get the contracts, we had to have the credibility, and to get the credibility, we had to have the contracts,” Rosenman says. Woodstock Ventures solved the problem by promising paychecks unheard of in 1969. The big breakthrough came with the signing of the top psychedelic band of the day, Jefferson Airplane, for the incredible sum of $12,000, double their usual pay for gigs. Creedence Clearwater Revival signed for $11,500. The Who then came in for $12,500, and the rest of the acts started to fall in line. “We paid Jimi Hendrix $32,000. He was the headliner, and that’s what he wanted,” Rosenman says.

The residents of Wallkill had heard of hippies, drugs, and rock concerts, but after the Woodstock advertising hit the major newspapers and radio stations, local residents knew that a three-day rock show [maybe the biggest ever] was coming. Woodstock Ventures’ employees looked like hippies, and in the minds of many people, long hair and shabby clothes were associated with left-wing politics and drug use. The new ideas about reordering society were threatening to many people, and the Wallkill Zoning Board of Appeals officially banned Woodstock on July 15, 1969, to the applause of residents. Two weeks earlier, the town board had passed a law requiring a permit for any gatherings greater than 5,000 people.

Long hair was referred to as the “freak flag” waved by hippies.

Contract for The Who to play at Woodstock.

“The law they passed excluded one thing and one thing only—Woodstock,” says Al Romm, then-editor of the Times Herald-Record, which editorialized against the law.

Paul Novak was growing up in Wallkill and lived about half a mile from what was to be the festival site. “I was only 14 at the time,” remembers Paul. “I was a budding guitar player and totally fascinated with the unfolding events… locals vs. hippies. I remember wandering up to the Wallkill site that summer, and even sneaking into the barn that the organizers were using as an office. From the outside, you could see hippies building a stage, but the inside of that barn was a beehive of activity filled with desks and telephones ringing. All those long-haired folks were so out of place in our little hick town. That stage was already half constructed when Wallkill wanted out. There were already so many people coming, and this scared a lot of folks. All the work that had been completed to that point was abandoned, and the structure sat for years—an unfinished monument to what might have been.”

Elliot Tiber read about Woodstock getting tossed out of Wallkill. He owned the El Monaco, a White Lake resort of 80 rooms with nearly all of them empty, and keeping it going was draining his savings. But for all of Tiber’s troubles, he had one thing that was very valuable to Woodstock Ventures: a Bethel town permit to run a music festival.

“I think it cost $12 or $8 or something like that,” Tiber said. “It was very vague. It just said that I had permission to run an arts and music festival. That’s it.” The permit was actually for the White Lake Music and Arts Festival, a very small event that Tiber had dreamed up to increase business at the hotel. Tiber called Woodstock Ventures, not even knowing whom to ask for. Lang got the message and went out to Elliot’s place the next day [probably July 18] to take a look around. Tiber’s festival site was 15 swampy acres behind the resort.

“Michael looked at that and said, ‘This isn’t big enough,’” Tiber recalls. “So I said, ‘Why don’t we go see my friend Max Yasgur? He’s been selling me milk and cheese for years. He’s got a big farm out there in Bethel.’”

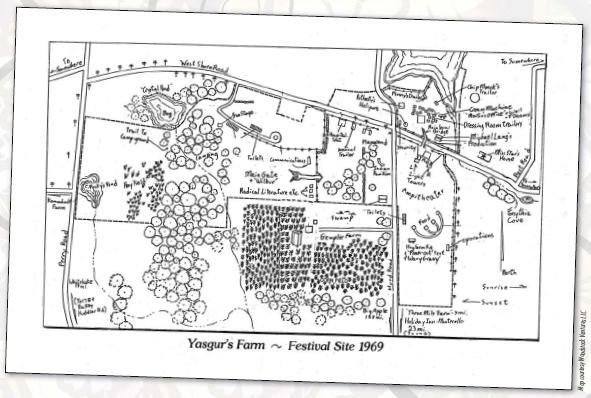

Original festival site design for Woodstock.

“It was magic,”Lang said It was perfect—for the stage, bowl, a little rise for the sloping, a lake in the background.

Something was tapped, a nerve, in this country, and everybody just came.

Yasgur met Lang in the alfalfa field. This time, Lang liked the lay of the land. “It was magic,” Lang said. It was perfect—the sloping bowl, a little rise for the stage, a lake in the background, and the deal was sealed right there on the spot.

Lang recalls, “Max and I were walking on the rise above the bowl. When we started to talk business, he was figuring how much he was going to lose in his crop and how much it was going to cost him to reseed the field. He was a sharp guy, ol’ Max, and he was figuring everything up with a pencil and paper, wetting the pencil tip with his tongue. I remember shaking his hand, and that’s the first time I noticed that he had only three fingers, but his grip was like iron. He’d cleared that land himself.”

Within days after meeting Yasgur, Lang brought the rest of the Ventures crew up, but by then, Yasgur was wise to Woodstock and the price had gone up considerably. Woodstock Ventures kept the negotiations secret, lest it repeat what had happened in Wallkill. The Woodstock partners have since admitted that they were engaged in “creative deception.” They told Bethel officials that they were expecting 50,000 people, tops, when all along they knew that Woodstock would draw far more.

“I was pretty manipulative,” Lang admits. “The figure at Wallkill was 50,000, and we just stuck with it. I was planning on a quarter-million people, but we didn’t want to scare anyone.”

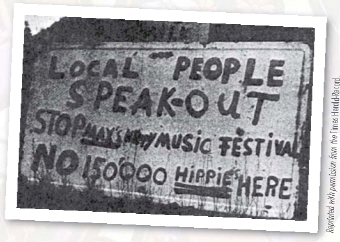

With Yasgur’s assistance, the appropriate permits were obtained, but as news of the festival spread, it stimulated local opposition. An anonymous party erected a 2-1/2 -by-4-foot sign that read, “Local People Speak Out/Stop Max’s Music Festival/No 150,000 Hippies Here/Buy No Milk.” The Yasgurs had been having second thoughts about their decision to lease their land, but after they saw that sign, they were determined to go through with it.

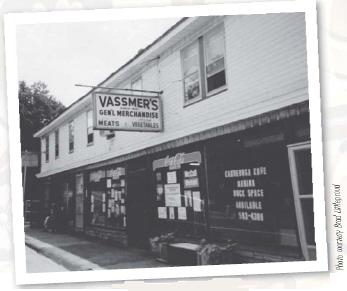

As July became August, Vassmer’s General Store in Kauneonga Lake was doing a great business in kegs of nails and cold cuts. The buyers were long-haired construction guys who were carving Yasgur’s pasture into an amphitheater.

“They told me, ‘Mr. Vassmer, you ain’t seen nothing yet,’ and by golly, they were right,” remembers Art Vassmer, owner of the store. Abe Wagner knew that little Bethel, with a population of 3,900, wasn’t set to handle the coming flood of humanity. Two weeks before the festival, Woodstock Ventures had already sold 180,000 tickets, and a week before the festival, Yasgur’s farm didn’t look much like a concert site. “It was like they were building a house, except there was a helicopter pad,” Vassmer says.

Vassmer’s General Store, Kauneonga Lake (Bethel), New York.

A Festival Site Rises from Max Yasgur’s Farm

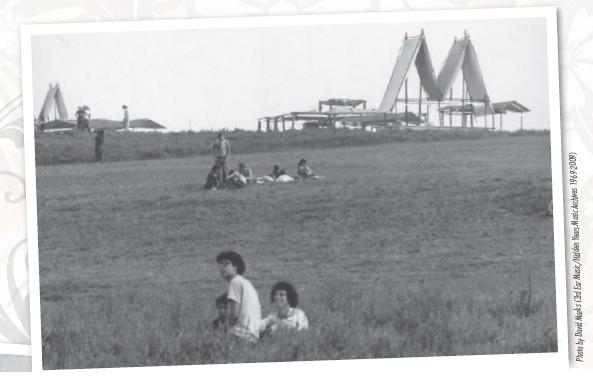

early Woodstock arrival looks toward the concession area in a pristine field.

An

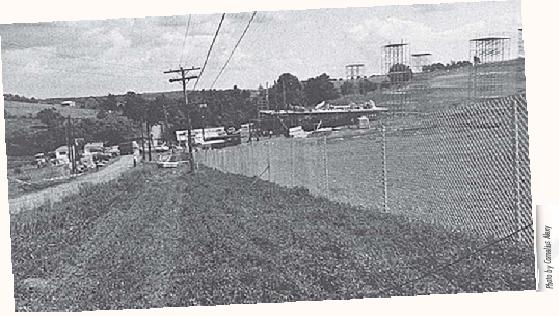

Performers pavilion being built behind newly installed fencing.

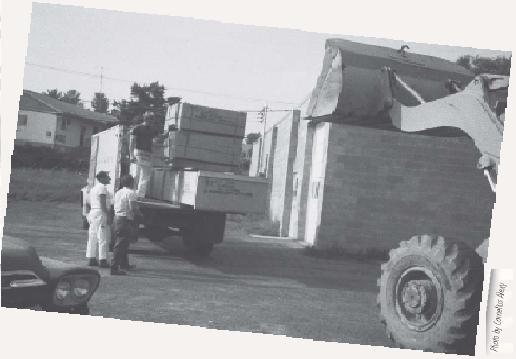

took immense amounts of lumber and plywood to build the Woodstock stage.

It

Building the stage.

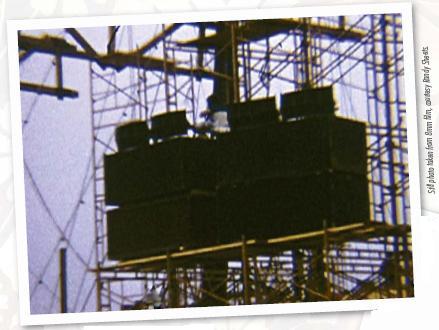

Massive cranes lift materials and raise sound towers. The stage was accidentally built around the cranes, making them impossible to remove.

Four scaffold towers are raised to hold the speaker system and lighting.

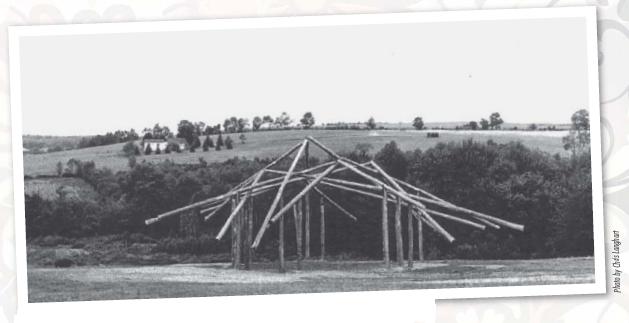

The performers pavilion was a log pole and tarpaulin design to complement the rural setting.

Thousands of tents, trailers and cars would take over the field behind the pavilion as one of many “unofficial” campgrounds.

The Indian pavilion was to showcase the arts and heritage of the East. As with the “Arts Fair” component of the festival, it did not materialize.

Chris Langhart submitted a design for the stage roof. It was rejected for the truss and sail design.

A view of West Shore Road that ran behind the stage. A wooden bridge was constructed across the road joining the stage to the back stage performers area.

As Aquarius rose in Bethel, Artie Kornfeld had bigger fish to fry. “What was paramount to the success of the festival was the need to ensure that the festival would be peaceful,” Kornfeld says. “At that time of unrest in America, I knew that I had to go meet with the Black Panthers, the SDS, and Abbie Hoffman, and become friends to divert any possible trouble prior to the concert. It took time, but I was able to get guarantees that ‘Three Days of Peace and Music’ would be just that.”

pass. Photo by David Marks (3rd Ear Music/ Hidden Years Music Archives 1969-2009) Staff

Lisa and Pilar Law.

Harriette Schwartz, 19, was born and raised in the Bronx, New York, and landed a great job after high school with Warner Bros./Seven Arts in the city. Because of this position, she learned of the plans for Woodstock. Michael Wadleigh, the filmmaker for the Woodstock documentary, and his crew had been given offices there in the Tisch Building at 666 Fifth Avenue.

“They were a bit different, sitting on their desks with their feet up on their chairs, but always pleasant enough,” Schwartz remembers. As often is the case in the workplace, everyone knew why they were there, and when a good-looking guy from the mailroom named Alan asked her to go to Woodstock, she said yes. Alan was from Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, and they drove up to Bethel the weekend before to check things out.

“Little did I know the prequel I was witnessing,” Schwartz says. “It was a huge, open, grassy cow pasture onto which these huge metal stanchions were being erected. It was a hilly, tranquil, and placid venue. The day was sunny, the sky was blue, and you never would have guessed that such a peaceful setting would become home to half a million celebrants dancing in the rain and mud, just one week later.”

Lisa Law, 24, of Santa Fe, New Mexico, remembers that at the 1969 Aspen Meadows Summer Solstice in New Mexico, Stan Goldstein [campground supervisor for Woodstock] asked the Hog Farm and the Jook Savages to handle the coordination of the campgrounds at the festival.

“Since we were a large communal group,” Law says, “he thought we would know how to take care of masses of people, especially if they were taking drugs, as we were well-versed on the subject. We agreed. Our party of about 85, with 15 Indians from the Santa Fe Indian School, turned up on the assigned day at the Albuquerque Airport to take the jumbo jet the organizers sent to fly us to the festival. [My husband] Tom and I decided to take our tepee. The handlers at the airport looked like Keystone Kops loading the poles into the baggage compartment. That had to be a first.”

Jean Nichols, 24, was returning to the United States from Vancouver, Canada, after the birth of her daughter. On the way, they stopped at Merry Prankster leader Ken Kesey’s farm, and from there she met up with the Hog Farm. Jean remembers, “We were told that we’d be setting up a place where the people would be camping, the free stage, plus we’d have our own space.”

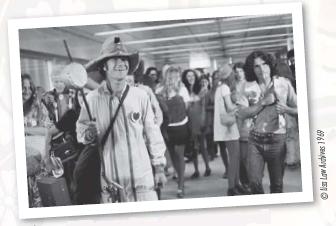

Thirty-three-year-old Hugh Romney [later taking the name Wavy Gravy, given to him by B. B. King], first among the commune’s equals, donned a Smokey-the-Bear suit and armed himself with a bottle of seltzer and a rubber shovel. When they stepped off the plane at Kennedy Airport on Monday, Aug. 11, the Hog Farmers were met by the World Press, who informed them they had also been assigned the task of doing security.

“My god, they made us the cops,” Wavy said. “‘Well, do you feel secure?’ I asked. The guy answered, ‘Yeah,’ so I said, ‘See, it’s working already.’ That’s when he asked what we were going to use for crowd control. I told him ‘cream pies and seltzer water.’” He and the members of the New Mexico commune constituted themselves as the “Please Force.”

Lisa Law remembers, “We got a flash that the concert was going to be a monster and we had better prepare for the onslaught if we were to take care of the masses of hungry souls who wouldn’t have enough food with them, or enough money to buy any, so somebody had to go into the city for supplies.”

Fellow Hog Farmer Peter Whiterabbit volunteered to be Law’s assistant, truck driver, and guide in New York City, where she’d been only once before. With $3,000 from the organizers, she purchased 1,200 pounds of bulgur wheat and rolled oats, two dozen 25-pound boxes of currants, almonds, and dried apricots, 200 pounds of wheat germ, five wooden kegs of soy sauce, and five big kegs of honey. She then bought five huge stainless steel bowls and 35 plastic garbage pails.

Compound for the Earth Light Theatre, who entertained the crowds at the free stage.

Hugh Romney, also known as Wavy Gravy, and the Hog Farm arriving at JFK.

“I figured we would feed some 150,000 people, so I bought 130,000 paper plates, spoons and forks and about 50,000 paper cups. While roaming around Chinatown, I bought a jade Buddha for good luck and to keep the kitchen crew blessed.

“While we were in the city, the crew on site was building the kitchen and the food booths. I had come up with a design for the serving booths, where two people could serve from either side, creating 10 lines for five booths,” Law remembers. “We got the kitchen functioning and everything cooking, and out of nowhere came 10 to 15 volunteers at a time, cutting and cooking and serving and having a great time doing it.”

About 2 a.m. Tuesday morning, Elliott Tiber recalls, “I didn’t sleep well. I woke up and I heard horns and guitars. I look out, and there are five lanes of headlights all the way back. They’d started coming already.”

Television actress Bonnie Jean Romney (nee Bonnie Beecher, later taking the name Jahanara) was 27 and married to Wavy. She was in charge of the kitchen and oversaw the crews.

1969Jahanara Romney in 1969.

Tickets for the contracted “Food for Love” concession stands.

About 2 a.m. Tuesday morning,

Elliott Tiber recalls, “I didn’t sleep

well. I woke up and I heard horns and

guitars. I look out, and there are five

lanes of headlights all the way back.

They’d started coming already.”

“Somehow I had access to this little scooter-type thing,” Jahanara remembers. “It was like a motorcycle with a wheelbarrow on the back. Yasgur’s dairy farm was just up on 17B, and they had a place where you could buy their products, so we made arrangements with them to get fresh yogurt, which I was able to get and bring back using this little vehicle. There were so many people already there that we started to serve on Tuesday.”

Eight miles away, Times Herald-Record harness racing reporter John Szefc was working on a feature story at the Monticello Raceway when he caught a glimpse of Route 17B. “It was 11 a.m., more than 24 hours before the concert, and traffic was already backed up all the way down Route 17B to Route 17, a distance of 10 miles. That’s when I knew this was going to be big. Really significant,” he says.

For Randy Sheets, 19, from Long Island, New York, it was the summer after his first year of college. “Late at night, my friend Chris and I would often lie on the rug in my parent’s living room, in front of a fan, and listen to WNEW FM, the New York City-based progressive rock station. My parents had long since gone to bed, and we would listen to the late night deejays, Rosco and Allison Steele, ‘The Night Bird,’ and their sultry, silken voices would somehow help cool the hot summer nights. That was where we started hearing talk of an August festival planned in upstate New York, called Woodstock. My younger brother, Scott, had already bought tickets (he still has them), and the week before the festival, the deejays were talking about the large crowds that were expected. No one had a car of their own, so we prevailed upon our parents to loan us the Ford Country Squire station wagon, and all was a go! We decided to head up early and try and avoid the crowds, so we set out on the Wednesday before.

This original “welcome sign” can still be found in Bethel, New York today. Courtesy of Larry Houman. In memory of Carol Hector Houman. (Owned by Jerry and Kay Hector)

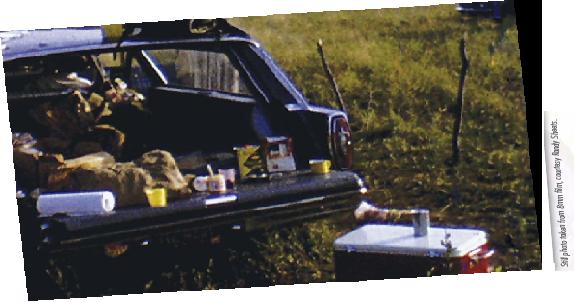

“Seven of us crammed in the car along with our camping gear—tent, sleeping bags, flashlights, Coleman stove, etc. —and some Goobers, a combination of peanut butter and grape jelly swirled together in a jar,” Sheets says. “In the car were my brother Scott, who was a year younger than me, his two friends, Bub and Curtis, my two friends, Chris and Peter, and the younger brother of one of Scott’s friends, Jimmy. Before we left, my father handed me his hand-winding 8mm movie camera and a few spools of film. He said he wouldn’t be needing it, so I might as well take it along.

“I don’t remember much about the drive up even though I was the one driving!” says Randy. “We knew where we were going, and as we got closer we saw hand-printed signs pointing the way. It wasn’t too difficult. All you had to do was follow the line. The traffic got heavier as we approached, and we drove until we saw some other folks parked on farmland up to the right. It was slow going for those last few miles with a steady stream of cars all bumper to bumper, and many people walking along both sides of the road. Some folks jumped on the front fenders of our car and got a lift and since we were only creeping along, this was easily accomplished. Food, weed, and drink were being shared among the walkers and the people in cars, and there was a real sense of being a part of something big.”

Heading off to History

Randy Sheets and friends getting closer to Woodstock.

Randy Sheets parents’ station wagon.

Randy’s view getting closer to the festival.

We quickly got used to jumping on to ‘hitch’ a ride, and everyone was just grooving on one another.

It was easier said than done.

Jimmy Acunto, 15.

“When I was 16,” recalls Greg Henry of Kearney, New Jersey, “I attended the Atlantic City Pop Fest in early August, where I met a lot of people talking about Woodstock, but I wasn’t sure if I could go. The reactions from my parents were mixed. Mom was excited and Dad just shook his head, but I got the ok and went with Bob Wall, my best friend. Neither of us had a car, so we used our thumbs and left early Wednesday morning.”

While so many others had to deal with traffic, Greg and Bob had their own set of problems to contend with. “We were stopped by a State Trooper on the New York Thruway, who didn’t seem to like us much or the fact that we were going to Woodstock. He made us empty our backpacks, which held a bunch of oranges, cheese, and a butter knife. I guess he wanted to be really thorough in his search and make sure we didn’t have anything illegal stuck in those oranges…so he proceeded to stomp on every one. He confiscated our butter knife, told us to be careful, and sent us on our way. Soon after, we were picked up by an army green car with insignias on the doors, and driving was a black gentleman wearing an Army uniform. Right off we thought it was pretty weird, but the ride was very welcome. I noticed a bandage on his wrist, and I could see blood seeping through. He was driving very fast and erratic and kept asking if we wanted to see his gun. Needless to say, we were very nervous by this point, but luckily we started to see a lot of people much like ourselves. We asked the guy to drop us off, but he continued on a few more miles. When he finally stopped the car, he was still insisting that he show us his gun and to our shock, he did, but it wasn’t what we were expecting. He opened his pants and exposed himself. ‘See my gun’ and with that…we were off and running.”

Randy Sheets, 19.

On approaching the “official” camping area, Randy Sheets and his friends remember seeing a relatively clear spot off in the fields. “We left the road, drove across the grass and parked among a dozen other cars and tents. We brought a tent, which we soon found leaked badly! Somehow it got set up, and we tossed in our gear, headed for the road, and began our march to the festival site. We quickly got used to jumping on car fenders to ‘hitch’ a ride, and everyone was just grooving on one another. There was this overwhelming feeling of togetherness. We arrived at the site and joined a large crowd that was headed towards a fence that had been rather haphazardly set up. We pushed the fence down very easily, and we headed toward the stage area. It really wasn’t a ‘pushing down’ as much as it was a ‘walking down.’ There was no malice; it was just meant to be down. We staked out our area, stage left about 10 rows back. They were really good ‘seats’ and we always made sure we had someone stay back to save them the entire time. We brought a couple of blankets to mark our spot and sit on, and at this point, we were all in a beautiful green meadow of knee high grass. When we found out that the music would last far into the night and early morning, we lugged all our sleeping bags over from the campsite.”

Randy Sheets’ friend, Jimmy.

Scott Sheets, 17, Randy’s brother.

Paul “Bub” Smith, 17.

Christmas lights were strung in the trees. Sawdust was strewn along the paths. Over the hill, carpenters were still banging nails into the main stage. The Merry Pranksters and the Hog Farmers had built their own alternative stage for anyone who wanted to jam, and the sound system was a space amplifier borrowed from the Grateful Dead.

“We heard music coming from an area to the side of the main stage,” says Sheets, “and we wandered down to see what was up. There we found three or four psychedelic buses and a low stage with people sitting around grooving on the music. It seems we happened upon the Hog Farm and the Merry Pranksters’ bus, ‘Further.’”

We found a place to park ,” said Randy Sheets.“

Fields became parking lots.

Dennis Himes, a 15-year-old from Ridgefield, Connecticut, went to Woodstock with his 17-year-old brother, Geoff, and his friend, Pete. Dennis remembers, “On Thursday night there was a concert on the free stage. I remember somebody making soap bubbles, and when a bubble would float up above the crowd, people would shine their flashlights on it, causing two bright dots of light on the bubble. With several flashlights on all the bubbles, it was a floating constellation of stars.”

The crowd gathers in the concert bowl.

Christmas lights were on the fences and in the trees.

Massive speakers perched on tall towers were being set up.

Psychedelic buses surrounded the free stage atthe Hog Farm encampment.

Mom and child in concession area.

Hog Farmer Jean Nichols recalls, “Early on, we were doing things to engage the people that were showing up, getting them to help. I remember having a bonfire one night and trying to make the world’s biggest marshmallow on a snow shovel by melting bags of marshmallows together. Everyone just went for that.”

“Wine bottles and joints made the rounds as we sat and enjoyed the varied company and listened to the music,” remembers Randy Sheets. “There was also a handful of little kids running around in various stages of undress— some naked, some with just a shirt. There was a real feeling of camaraderie and fun. Everyone was out to enjoy and have a peaceful time, and this feeling would pervade my entire Woodstock experience. We hung out there until early evening and then walked back to our spot in front of the stage and watched as final preparations were made with lighting, sound, and completing the setup of the stage. This was only Wednesday, so final setup was in full swing.

“As it got dark, we figured it would be a good idea to find our campsite, which we managed, and folks were still sitting around their sites playing guitar and sharing what they had. One in our group found a long tree branch and rigged up the British flag that my brother had brought along, and that stood over our site. My brother, Scott, was into the British bands and everything British. We made some Goober sandwiches and slept, crowded into our tent.

“The next day, Thursday, was much the same—hanging out and grooving on the scene,” Sheets continues. “We actually got up that morning and made blueberry pancakes on our Coleman stove! The blueberries were picked from some bushes that surrounded our meadow, and someone had brought boxed pancake mix. Our pancakes stuck without any oil, but we didn’t care. They were so good!”

“Hoisting our flag,” says Randy Sheets.

Blueberry pancakes.

I remember having a bonfire one night and trying to make the world’s biggest marshmallow on a snow shovel by melting bags of marshmallows together.

Traffic on Route 17B.

Debbie Stelnik today.

Traffic on Route 17B.

White Lake local Debbie Stelnik recalls, “I was 11 and staying at a bungalow colony off 17B with my parents and sister. We were in the woods within walking distance from White Lake, right in the midst of all the people trying to find their way to the grounds. I remember the adults were scared, including my mom. Sure, we were used to a lot of middle-class urbanites traveling to the area for the summer, but nobody had ever seen anything like this. This was a relatively quiet place, and then all of a sudden here are all these people just walking through everyone’s property. People were looking for food, water, or a place to sleep. A couple from Poland owned the colony, and they were absolutely freaking out. At night they stood guard with shotguns. The traffic was so incredible and my dad wanted to take a look, so we filled some water jugs and Dad passed it out as we went along. Everyone was so grateful, saying, ‘Peace, man. Thanks.’”

Campers take over the adjacent fields.

By Thursday afternoon, Aug. 14, Woodstock was an idyllic commune of 25,000 people. The Hog Farmers had built kitchens and shelters with two-by-fours and tarps. Their kids were swinging on monkey bars built from lumber and tree limbs, jumping into the hay below. Wavy Gravy recruited responsiblelooking people and made them security guards. He handed out armbands and revealed that the secret backstage password was “I forget.”

Twenty-three-year-old Alan Futrell of Sanford, Florida, was ex-military and involved in the antiwar movement. He met a few people who were talking about the event, and though he wasn’t one for concerts, he decided to hitch up and see if he could get in.

“I arrived on Thursday, and everyone was working frantically to get the stage and sound system finished,” Futrell remembers. “I camped on the hill near the buses and volunteered to help the crew keep the place clean, just so I could get in.

“People were camped everywhere, a mass of tents and shelters. I spent much of my days roaming around, and I’d go back to the buses at night. I had a small backpack, and what I found was that I could actually leave it lay anywhere and not worry about anyone stealing; no one touched anyone’s stuff. That was one of the main impressions I had—no worries.

“There was always some kind of food available. There were certain areas where you needed to buy it, but you really didn’t need money, most of the people just welcomed you in. Whatever you needed seemed to be available through the people. It was very much communal living in the hippie sense.”

“The stage was still being completed and there had to be thousands of people there already,” recalls Greg Henry. “We were in the middle of the field while they were putting up a fence all around us. We fell asleep, and when we woke up, the fence was gone.”