CHAPTER SEVEN

DIRECT INSPIRATION TO DESIRED OUTCOMES

“The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second-best time is now.”

—Ancient Chinese proverb

The spark of inspiration represents potential—the potential for an idea to go from concept to reality through action. But a spark is really just a starting point. Without purposeful, volitional attention or action, it dies out; the idea goes nowhere.

For example, what if roommates Joe Gebbia and Brian Chesky were content simply to rent out their loft to make some extra rent money rather than rolling out their idea worldwide as Airbnb? Or if Blake Mycoskie of TOMS, on witnessing Argentinian children without shoes, had simply written a check to buy shoes for the village rather than designing a business model that would provide an ongoing supply of shoes? What if Maggie Doyne of BlinkNow had been inspired to pay for one child’s school tuition and continued on her trek through Nepal rather than staying and building an orphanage and adopting dozens of children? What if Malala Yousafzai had focused on obtaining her own education rather than fighting for the right for all girls to receive an education?

Thankfully, the leaders in these stories did not stop once they felt a flicker of inspiration. Instead, they autonomously and intentionally put their inspiration into practice. They set their sights on the success they envisioned, drove forward, and were strategic and tenacious in their pursuit of goals.

Still, in all these cases, if the spark of inspiration had been allowed to fade rather than fed with encouragement and action, we would never have seen new business models emerge, or these social initiatives take hold. That’s the difference between feeding a spark to reach a desired outcome and merely allowing it to fade and die out.

That initial spark of inspiration feels good, it’s uplifting, but again, it can be fleeting. Another pathway to sustaining inspiration comes from directing your attention and effort toward a particular outcome, which converts that spark into a steady flame. Taking action is what transforms an idea into an outcome.

The process of applying meaningful action to a spark to achieve a positive impact is, in and of itself, inspiring. It’s the translation of the emotion of inspiration into successful performance, of taking a spark and making it last over time by translating it into behaviors that will result in desired outcomes.

SUSTAINING INSPIRATION THROUGH DIRECTED ACTION: FOUR CATEGORIES OF BEHAVIOR THAT LEAD TO DESIRED OUTCOMES

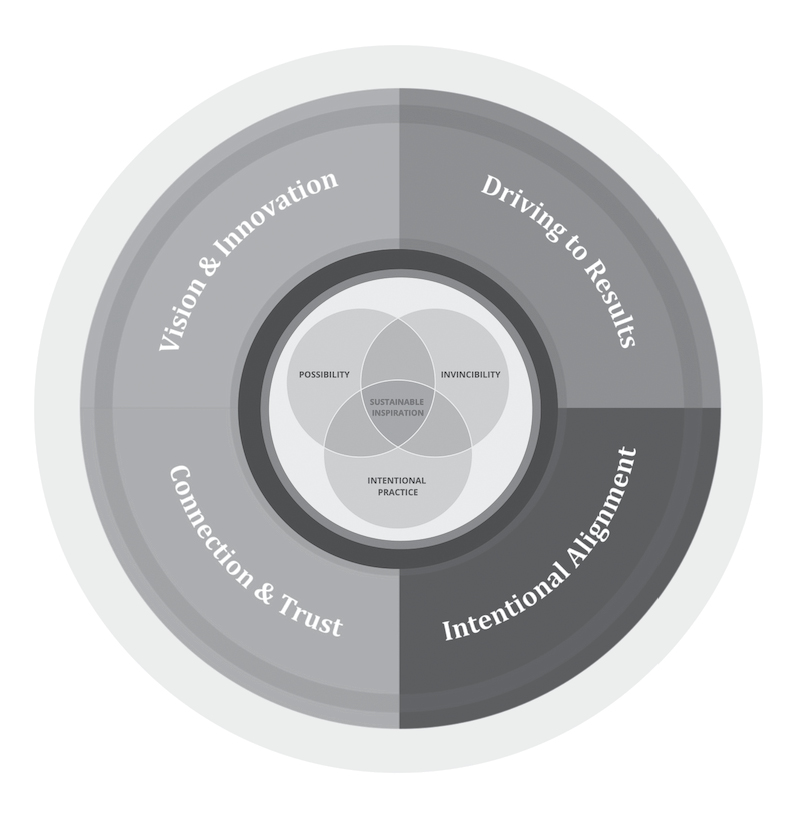

We have identified four specific categories of behavior—driving to results, intentional alignment, connection and trust, vision and innovation—that are most useful when directing inspiration to positive outcomes. These four categories of behavior are consistent with what we know from working with our clients and from existing research. For example, the CEO Genome study1 of seventeen thousand executives discovered that high-performing executives exhibit four behaviors consistently, setting them apart from average or subpar C-suite execs. These behaviors were

• Deciding with speed and conviction. Even with incomplete information, successful leaders “make decisions earlier, faster, and with greater conviction,” reported Harvard Business Review.2

• Delivering reliably. Consistently delivering results was perhaps the most important behavior of all four, the researchers found. “Boards and investors love a steady hand, and employees trust predictable leaders” was the summary.

• Engaging for impact. They work hard to get buy-in from employees and important stakeholders.

• Adapting proactively. Most CEOs juggle thinking about the short-, medium-, and long-term implications and adapt as needed, though the study found that more successful CEOs spent at least 50 percent of their time pondering long-term implications.

Inspired executives successfully exhibit behaviors that correspond to these four categories.3

Additional support is found in The Leadership Code. David Ulrich and his team report that successful leaders display four behaviors, namely human capital developer, strategist, executor, and talent manager.4

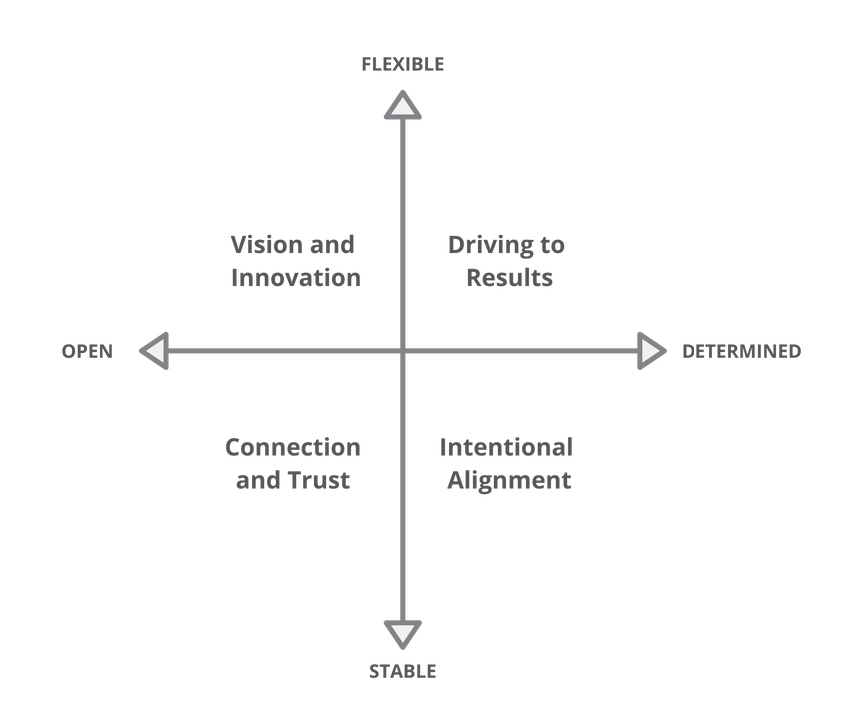

The four categories of behavior we advance here are informed by the research above and emerged from two critical continuums of behavior that pose interesting paradoxes to be wrestled with to achieve success. One continuum spans from openness (to ideas and people) to determination (think task driven). The other continuum goes from grounded stability to dynamic flexibility. These two dimensions encompass behaviors shown to be most effective at driving success. When we cross these two dimensions, they create four key categories of behavior: flexible/determined, determined/stable, stable/open, and open/flexible.

These four categories of behavior have been shown to, together, yield success through agility and balance across all four. We’ve named them to reflect the central organizing principle that comes from the blend of the two dimensions represented. They are driving to results, intentional alignment, connection and trust, and vision and innovation.

Driving to results (flexible/determined). Key to successful outcomes are ambitious goals and the drive to achieve them. Directing inspiration toward driving to results includes goal setting, defining desired outcomes, and identifying the actions to reach success (think Mycoskie creating TOMS Shoes or Avila with his taco trucks). What strengths of yours will be useful in achieving your goals? How will you know if you’ve reached them? Flexibility can afford asking the question, Is there a better, faster way to proceed?

Intentional alignment (determined/stable). A results focus is useful but can be detrimental if it is rash or reckless (think of big banks in 2008). This is where intentional alignment comes in to ensure that goals being achieved and decisions being made are rooted in your values. Integrity is a big part of intentional alignment. It protects reputation, accountability, and reliability. As you are working toward your ambitious goals, ask yourself: Are you really defining success in alignment with your values? What risk can you tolerate and how do you mitigate higher levels of risk? What standards or regulations will you uphold to succeed?

Building connection and trust (stable/open). Success rarely happens in isolation—we are wired to be connected to one another. Building connection and trust is key to forging relationships with others who can support you and your efforts (think Gebbia and Chesky focusing on how to build enough trust between strangers so that both guests and hosts feel safe—critical to cracking the Airbnb code).5 What can you do to garner support from those around you who matter? How will you share the joys of winning together? What can you do to better support others as they work toward your common goals?

Vision and innovation (open/flexible). The ability to visualize and create a desired future for yourself is key to achieving it. Using vision and innovation, you brainstorm and envision new ways of progressing toward your desired result or even new desired results (think Captain Irving developing the Flying Classroom curriculum for children around the world to learn about aviation). Achieving your goal will likely require zigging and zagging rather than proceeding on a straight line. What unconventional steps can you take to move forward? What new approach might work even better than what you originally planned?

Imagine a result you aspire to achieve. That might be increasing revenue in your business unit by 10 percent this quarter, reducing overtime pay, coming up with a revolutionary new product idea, or developing a new way to increase visibility within your target market. Whatever your desired outcome, investing time and attention across the four categories described previously will generate the best results.

WHY IT’S IMPORTANT TO DIRECT INSPIRATION TO PERFORMANCE AND POSITIVE IMPACT

Part of the reason that Airbnb and TOMS shoes now exist is that humans have an innate desire to express their capabilities and to succeed, according to humanistic psychology.6 That drive toward self-actualization is why sparks of inspiration are often sustained. Humanistic psychology, which became prominent in the mid-twentieth century, states that expressing one’s own capabilities and creativity is human nature. That is, reaching our full potential and being successful is our ultimate goal.

“When at a top level of inspiration, it feels incredibly productive—there is a sense of accomplishment; you feel like you’re making the right moves. It’s like an athlete when they are locked in and keep hitting their shots; it’s coming a little easier. It’s all that practice that they have been putting in, and sometimes it works better than other times, so when it all falls into place a little bit easier, that’s an incredible feeling.”

—James Grady, Assistant Professor of Fine Arts and Design, Boston University

Striving toward a particular outcome we have envisioned is inspiring to us. The act of working toward a particular goal feeds that spark of inspiration. According to humanistic psychology, human beings set goals and strive to achieve them, seeking meaning, value, and creativity in the process.

Success also breeds success.7 The more we work toward a goal and achieve it, the more we are inspired to continue striving. This process of goal accomplishment or achievement is essential to our own well-being, according to research by Martin Seligman.8 Because as we strive toward achievement, we stretch our knowledge base and learn new skills. By attempting new experiences and succeeding, we boost self-efficacy. Our capacity for self-efficacy develops over time the more we try new things, try new experiences, and witness achievement.9

Self-efficacy results from realizing success from possibility and invincibility. The more we strive, the more we attempt to achieve, the more we are capable of achieving and the more we are willing to try. Teresa Amabile’s and Steven Kramer’s10 progress principle supports this positive spiral. They show, in their book The Progress Principle, that progress toward achieving meaningful goals is hugely motivational. Again, the more we achieve, the more we want to keep going.

People who sustain their inspiration put it into practice in specific ways—not just taking random action but instead translating their spark of inspiration into action across the four categories that, together, lead to heightened positive results.

PUTTING THE FOUR BEHAVIOR CATEGORIES OF INTO PRACTICE

The idea of enacting behaviors in these four categories is simple and attractive. But what does it actually look like to do it?

USING INSPIRATION TO DRIVE TO RESULTS

KEY BEHAVIORS

• Set ambitious goals

• Gather and utilize resources

• Activate strengths

• Create a plan

• Clear obstacles to action

• Mobilize commitment

You are probably familiar with the story of the Jamaican bobsled team thanks to the movie Cool Runnings. Although the movie is a fictionalized version of the tale, what is less known is the behind-the-scenes work that it took to make the team a reality. Those efforts illustrate the drive to results.

The Jamaican Olympic bobsled team that competed at the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics—the first time any Jamaican team had competed at a Winter Olympics—was actually inspired by a friendly challenge given to former US government official George Fitch. During a conversation with his tennis partner while on the island of Jamaica, Fitch commented that there was no reason Jamaican athletes couldn’t be competitive at the summer and the Winter Olympics. After all, many of the skills and talents required for success carried over, he asserted. This idea inspired Fitch, who felt the notion of sending a team to the Winter Olympics might actually have merit.11

While contemplating what Olympic sport might be a fit for athletes used to tropical weather, Fitch heard about the annual pushcart derby being held the next day on the island. He realized the similarities between the pushcart race and bobsledding, which might make an Olympic appearance possible.

“Half the race is how quickly you can push a 600-pound object before you jump, and then the driver just lets the sled steer itself,”12 he explained to ESPN. His was an ambitious goal, but he was confident the local athletes had the innate talent to make a strong showing.

That was the spark that led Fitch to begin a six-month effort to get a Jamaican team to compete in the Winter Olympics. But rather than let the idea fade, Fitch took steps to make a Jamaican bobsled team a reality. He first approached the Jamaica Olympic Association with the idea to form a bobsled team. They approved, so he began researching coaches and available training facilities, landing on Austria and Lake Placid, New York. Then he found his athletes.13

Legend has it that he recruited local track stars, but one of the Jamaican Olympians disputes that tale, explaining that Fitch turned to the Jamaican army and found his competitors there, according to Dudley “Tai” Stokes. Stokes and teammate Devon Harris were two members of the Jamaican Olympic team.

Fitch’s goal was clear from the outset: get a Jamaican team to the 1988 Winter Olympics, which were less than six months away. Stokes confirms that the first time he laid eyes on a bobsled was in September 1987. In February 1988, he was competing at the Olympics. In between was intensive training.

As obstacles arose, Fitch found ways around them, because he was inspired by the goal of giving the team the best odds of success. He was truly driven.

Consider the following questions to develop behaviors that translate your spark of inspiration within the category of “drive to results”:

• What ambitious goals should we be focused on?

• Which of our individual strengths can each of us use to achieve them?

• What obstacles do we need to overcome to clear a pathway to success?

USING INSPIRATION TO CREATE INTENTIONAL ALIGNMENT

KEY BEHAVIORS

• Know your values

• Protect your values

• Align your goals to your values

• Work with integrity and credibility

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for her failure to give up her seat on a public bus to a white passenger. She was properly seated in the “colored” section, but since the “white” section was full, the bus driver asked her to give up her seat so that a Caucasian passenger could sit. She said no, not because she was tired, as has been widely reported, but because she had reached her own personal limits of mistreatment due to the color of her skin.

Her refusal triggered a series of events that ultimately led to the repeal of segregation on buses. But that action was not the result of a well-thought-out plan to raise awareness of segregation or to signal anything other than the fact that, as Parks says, she was just tired of giving in. She was inspired to take a stand and was arrested.

“I had not planned to get arrested. I had plenty to do without having to end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn’t hesitate because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became,” she explained in an NPR interview in 1992, cited in an article on the website The Undefeated.14

Parks said no because it was in alignment with her own personal beliefs about fairness. She was sparked to take a stand against injustice, in the hopes that she might inspire others to do the same. That spark was then sustained by the actions she had to take to defend herself and to inspire others to take a similar stand in the name of civil rights.

This single act of defiance is now credited as one of the defining moments in the birth of the civil rights movement. Inspiration is contagious.

Consider the following questions to develop behaviors that translate your spark of inspiration in this category of “intentional alignment”:

• In order to achieve our goals, what do we need to learn or know?

• How do our goals align to a larger context, our team values, or our higher purpose?

• How will we persevere in achieving our goals, even when we have setbacks?

USING INSPIRATION TO BUILD CONNECTION AND TRUST

KEY BEHAVIORS

• Connect and collaborate with others

• Find common ground and common goals

• Give trust to build trust

• Consider a broad array of others’ perspectives

• Attend to others’ emotions

One advantage the cofounders of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have is their marriage of more than two decades, during which they’ve built deep connection and trust with one another. That bond allows them to work collaboratively on many issues the foundation is concerned with, but especially combating poverty and health issues in developing countries and reforming the US education system. Yet while the Gateses are of like mind when it comes to what needs to be done, they often approach the problems and the solutions from different angles, explains Melinda Gates. A Fast Company article describes this dynamic in the following way: “Bill looks at the statistics surrounding various issues, while Melinda operates with more intuition, looking at the human stories that data doesn’t always reveal.”15

Their complementary approaches to assessing situations and developing potential philanthropic solutions sustains their inspiration. Part of the reason for their success as partners appears to be their sincere interest in the other’s perspective. Recognizing that they see things through different lenses, they appreciate hearing what the other has noticed. That appreciation for the other’s view has strengthened their relationship and the work they’ve been able to do together through the foundation. It’s a reflection of their connection and trust.

Said Melinda at a 2014 TED Talk: “I know when I come home, Bill is going to be interested in what I learned. And he knows when he comes home, I’ll be interested. We have a collaborative relationship.”16

Melinda Gates explains that their shared vision for the work to be done keeps the couple grounded and in alignment and this “grist” in their conversations helps them grow and deepen their understanding of each other. Despite differing opinions from time to time, their discussions and mutual goals help sustain their productive collaboration. That back and forth, information sharing, data analysis, and reflection on their priorities keeps them excited about making a positive difference in the world. Granted, they don’t always succeed, but they keep striving.

Bill Gates describes one of their failures: “So we spent, you could say wasted, five years and $60 million on a path that had a very modest benefit” to treat leishmaniasis, a rare tropical parasitic disease. They lean on each other during such failures, to chart a course forward and build on what was learned. Staying connected to what matters to them, as a couple, keeps them inspired.

Consider the following questions to develop behaviors that translate your spark of inspiration in this category of “connection and trust”:

• What binds us as a team?

• How can we share success?

• How can we show care and trust for one another?

USING INSPIRATION TO ADVANCE VISION AND INNOVATION

KEY BEHAVIORS

• Challenge status quo

• Create and communicate bold vision

• Develop a strategy

• Embrace innovation and change

• Activate positive emotions in self and others

A photograph on the front page of the New York Times of a Yazidi refugee and her children walking toward mountains in Iraq caught Hamdi Ulukaya off guard.17 The CEO of Chobani says the image reminded him of his native Turkey, and the haunting, empty look in the woman’s eyes inspired him to do something to help. He didn’t know what he could do, but his own experience drove him to try and do something positive.

He started by calling the United Nations Refugee Agency and the International Rescue Committee the next day. He couldn’t sit back and do nothing, he felt. Next, he created an organization, the Tent Foundation, to meet the humanitarian needs of refugees, which he believes is one of the biggest crises the world has faced since World War II.

As previously described, he also took steps to hire more refugees at Chobani, to create new opportunities for them. Today, 30 percent of the Chobani staff are refugees, and twenty different languages are spoken inside the company’s facilities. Says Ulukaya,

If you want to build a company that truly welcomes people—including refugees—one thing you have to do is throw out this notion of ‘cheap labor.’ That’s really awful. They’re not a different group of people, they’re not Africans or Asians or Nepalis. They’re each just another team member. Let people be themselves, and if you have a cultural environment that welcomes everyone for who they are, it just works.18

Rather than ignoring the issue of refugees, Ulukaya was moved to consider what he could do to help people who were a lot like him—people who had left or been forced out of their homes, with nowhere to go and an uncertain future. He approached the issue from a macro- and a microperspective, helping care for refugees abroad and helping to settle and provide for refugees who had arrived in the Upstate New York community where Chobani was based.

Ulukaya was sparked to find a new way of helping refugees in need. Instead of providing a safe haven for vulnerable immigrants, he had the vision to provide a means for them to find their own success in the United States, all while advancing his own business.

Consider the following questions to develop behaviors that translate your spark of inspiration in this category of “vision and innovation”:

• If there were no constraints, what could we achieve?

• In what ways can we iterate, experiment, and learn from the process?

• In what ways can we activate positive emotions in ourselves?

A FINAL NOTE ON AGILITY IN PERFORMANCE

Altogether, these four categories are essential to performance. Being able to move in and out of them, combine them, blend them, and monitor levels of each is critical to putting them into successful practice. We call this blending and movement across all four agility.

By focusing time and attention in all four of these categories, you can coax a spark of inspiration into a sustainable flame that leads to unexpected results and accomplishment. Focusing solely on one area won’t be sufficient to sustain inspiration: attention needs to be paid to all four. The four categories are interdependent, interconnected; focusing too much on one category leads to lack of activation in another, which can stunt overall performance.

Effective agility, including recognizing and engaging in one category when it is particularly useful, requires self-awareness and swift adjustments from one category to another. In other words, you have to know which categories you are focusing on and how to shift your focus so you are balancing all four. Sometimes shifting across categories can feel jarring or unnatural, and yet in this discomfort lies the opportunity for stretch and growth.

For example, Ulukaya at Chobani was clearly innovative as we highlighted above. But he also showed a drive to results by building a successful company; intentional alignment by taking action to protect refugees and affect policy at the highest level, despite many obstacles and even death threats; and connection and trust by providing a good life for refugees, including employment, benefits, paid leave, and even equity in the company.19

Sustaining inspiration comes from achieving desired outcomes. Achieving desired outcomes comes from directing activity across the four categories described above. Take what inspires you into these four categories to create outcomes that feel good, that fulfill you, and that have lasting positive impact.