Smyrnium olusatrum

Smyrnium olusatrum

alexanders • black lovage

Back to “Culinary herbs: alexanders (Smyrnium olusatrum)”

Smyrnium olusatrum L. (Apiaceae); swart lavas (Afrikaans); maceron (French); Schwarze Gelbdolde, Schwarzer Liebstöckel (German); salsa de cavalo, apio dos cavalos (Portuguese); apio caballar, olosatro (Spanish)

DESCRIPTION The leaves are large, pinnately compound and bright green with broad, serrated leaflets. They have a sharp flavour and fragrance reminiscent of myrrh and celery (hence the generic name).

THE PLANT A robust biennial herb of up to 1.5 m (ca. 5 ft) high, growing from a thick taproot and superficially similar to angelica or celery. When it flowers in April to June of the second year, the difference becomes more obvious. The umbels are flattened and bear greenish yellow flowers. The fruits are typical dry schizocarps that split into two mericarps – about 6 mm (¼ in.) long, and black in colour when ripe.

ORIGIN The plant is indigenous to the eastern Mediterranean region, where it grows on cliffs and in marshy areas near the sea.1,2 The Greeks called it hipposelinon which means “horse celery”. It became naturalized in Britain, the Netherlands and the Iberian Peninsula after it was introduced by the Romans as a food plant.3 The name alexanders is said to reflect the popularity of the herb in the time of Alexander the Great (fourth century BC). It was commonly grown in monastery gardens in the Middle Ages and in kitchen gardens (e.g. at Versailles in France). The roots, leaves and stems were eaten as vegetable and culinary herb in much the same way as celery and parsnips, with which it has been replaced around the 18th century.3,4

CULTIVATION Plants are easily propagated from seeds, sown in autumn and planted out in early spring.3 It is a forgotten culinary herb, no longer grown commercially to any extent, but is still commonly seen in herb gardens in Europe.

HARVESTING The stems and leaf stalks are cut in late spring, before the plants flower and the stems become hollow and fibrous. They are peeled in much the same way as rhubarb.3

CULINARY USES Young leaves and stems can be added to soups, stews and salads.3 They can be used on their own, boiled briefly for six to eight minutes and served with butter and black pepper.3 The flavour is similar to that of celery but stronger and more pungent.3 The flower buds are also edible.1,4

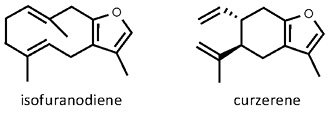

FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS The roots and above-ground parts contain an essential oil rich in furanosesquiterpenoids, of which isofuranodiene is the main constituent (up to 45%).5 The compound is converted to curzerene when heat is applied during steam distillation.5 The oil also contains β-myrcene, β-phellandrene and β-caryophyllene.

NOTES Skirret (Sium sisarum) and baldmoney (Meum athamanticum) are two other umbelliferous herbs that are no longer popular but which were once of considerable importance as root crops in Britain and other parts of Europe, where they were used in much the same way as parsnips. The aboveground parts served as culinary herbs and flavourants for the same purposes as celery does today.

1. Mabberley, D.J. 2008. Mabberley’s plant-book (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

2. Randall, R.E. 2003. Smyrnium olusatrum L. Journal of Ecology 91: 325−340.

3. Phillips, R., Foy, N. 1992. Herbs. Pan Books, London.

4. Kiple, K.F., Ornelas, K.C. (Eds). 2000. The Cambridge world history of food. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

5. Maggi, F., Barboni, L., Papa, F., Caprioli, G., Ricciutelli, M., Sagratini, G., Vittori, S. 2012. A forgotten vegetable (Smyrnium olusatrum L., Apiaceae) as a rich source of isofuranodiene. Food Chemistry 135: 2852−2862.