Wasabia japonica

Wasabia japonica

wasabi

Back to “Spices: wasabi (Wasabia japonica)rh”

Wasabia japonica (Miq.) Matsum. [= Eutrema wasabi (Sieb.) Maxim.; = Wasabia wasabi (Sieb.) Makino] (Brassicaceae); wasabi (Afrikaans); shan yu cai (Chinese); bergstokroos (Dutch); raifort du japon, raifort vert (French); Wasabi, Japanischer Kren, Japanischer Meerrettich (German); wasabi (Japanese, Korean); raiz-forte (Portuguese); wasábia, rabanete japonês (Spanish); Japansk pepparrot (Swedish)

DESCRIPTION The vertical, underground stems (often referred to as “roots”) are thick and fleshy, with scars left where the leaves have been cut off. When chewed, they have an extremely pungent but short-lived flavour and odour.

THE PLANT A stout perennial herb with thick stems, large, pumpkin-like leaves and small white flowers. The species is sometimes placed in the genus Eutrema and is then called E. wasabi.1

ORIGIN Indigenous to Japan1 and traditionally wild-harvested along mountain streams.2 In conservative Japanese restaurants, graters made from shark skin are still used when preparing fresh wasabi. It is an integral part of the Japanese culinary tradition and is therefore often referred to as Japanese horseradish (or the equivalent of this term in various languages).

CULTIVATION Propagation is mainly from seeds and this relatively new crop is either grown in normal soil or in running water under 50% shade cloth, using hydroponic methods. Wasabi is very difficult to grow and as a result the products are very expensive. Several cultivars are grown commercially in Japan (including the popular ‘Daruma’ and ‘Mazuma’) and in recent years also in New Zealand, Canada and the United States.

HARVESTING Whole plants are harvested by hand and the thick stems (vertical rhizomes) are trimmed to remove the leaves and roots. These fleshy stems are sold fresh or are processed into dried powder or ready-to-use pastes in tubes.2 Wasabi products sold outside of Japan often do not contain any wasabi but are made from horseradish, mustard, starch and green food colouring.

CULINARY USES Wasabi is extremely pungent, affecting not only the tongue but also the nasal passages and the eyes, causing tears. It can be quite painful if too much is taken at once. There is no long-lasting effect as with chilli peppers because the compounds are volatile, water-soluble and easily diluted or washed away. The pungency of freshly prepared wasabi is short-lived and evaporates after 15 minutes. Wasabi is an important condiment in Japan, alongside soy sauce (or often mixed with it) and gari (thin slices of pickled young ginger, usually pinkish in colour). The paste is commonly provided at the table as a dip with sashimi (fresh fish), sushi (the Japanese version of the sandwich but using sweet-and-sour rice instead of bread), tempura (deep-fried vegetables in a light batter) and noodle dishes. Wasabi leaves are also eaten as a vegetable.

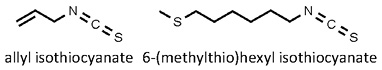

FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS Wasabi has the same main isothiocyanate as other members of the family Brassicaceae (e.g. horseradish and black mustard), namely sinigrin, a tasteless compound that is enzymatically converted to the volatile and pungent allyl isothiocyanate when moisture is added). However, what gives the unique flavour to wasabi is the additional presence of methylthioalkyl isothiocyanates, including 6-(methylthio)hexyl-, 7-(methylthio)heptyl- and 8-(methylthio)octyl isothiocyanate.

NOTES Fried or roasted wasabi-coated peas, peanuts and soybeans have become popular as crunchy snack foods.

1. Mabberley, D.J. 2008. Mabberley’s plant-book (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

2. Hodge, W.H. 1974. Wasabi: Native condiment plant of Japan. Economic Botany 28: 118−129.

3. Ina, K., Ina, H., Ueda, M., Yagi, A., Kishima, I., 1989. ω-methylthioalkylisothiocyanate, in wasabi. Agricultural Biological Chemistry 53: 537–538.

4. Masuda, H., Harada, Y., Tanaka, K., Nakajima, M., Tabeta, H. 1996. Characteristic odorants of wasabi (Wasabia japonica Matum.), Japanese horseradish, in comparison with those of horseradish (Armoracia rusticana). ACS Symposium Series, No. 166 (Biotechnology for Improved Foods and Flavors), Chapter 6, pp. 67–78.