Alpinia galanga

Alpinia galanga

greater galangal • galangal

Back to “Spices: galangal, greater (Alpinia galanga)rh”

Alpinia galanga (L.) Sw. (Zingiberaceae); groot galanga (Afrikaans); dà gao liang jiang (Chinese); galanga (French); Großer Galgant (German); laos (Indonesian); galanga (Italian); lengkuas (Malay); galang (Spanish); kha (Thai)

DESCRIPTION The rhizomes superficially resemble fresh ginger but are more robust (about 50–100 mm / 2–4 in. in diameter), less flattened and have a pinkish colour. It is also known in English as galanga, laos or Siamese ginger1 (but galingale is Cyperus esculentus). Rhizomes are sold fresh, sliced and dried or as a powder. It has a very pungent taste and a somewhat peppery flavour.

THE PLANT Galangal is a leafy perennial, up to 3.5 m (nearly 12 ft) high, similar to ginger but much more robust.1 The plants rarely flower in cultivation. Lesser galangal (Alpinia officinarum) is superficially similar but much smaller (up to 1.5 m / 5 ft in height) with attractive (but infrequent) white and purple flowers. It is in turn larger than the poorly known small galangal (Kaempferia galanga), also called Chinese galangal or shan nai.

ORIGIN Greater galangal is indigenous to Indonesia and other parts of tropical Asia. It is commonly cultivated as a spice in Thailand, Malaysia and Laos. Galangal was commonly used in European cooking during the Middle Ages and is still used as a flavour ingredient in digestive bitters and liqueurs. The galangal mentioned in old literature may be of Chinese origin and is then more likely to refer to lesser galangal or gao liang jiang (A. officinarum). This species has been used since the Middle Ages in eastern Europe and Russia to flavour teas and alcoholic beverages. Yet another species is small galangal (Kaempferia galanga) believed to be of Southeast Asian origin. It is the kencur of Indonesian cuisine (used fresh, e.g. in Malaysian nasi ulam) and the dried sha jiang (sand ginger) of Chinese (Sichuan) cookery (the plant is called shan nai).2

CULTIVATION Greater galangal is widely cultivated in tropical regions. Hot, humid conditions and light soils are required. Propagation is achieved by dividing the rhizomes.

HARVESTING There is no definite season and rhizomes can be harvested at any time of the year, while they are actively growing.

CULINARY USES Galangal is characteristic of Malaysian and Thai cooking. Slices of the tough rhizome (or large chunks, vigorously bruised to release the flavours) are added to curry dishes and soups. The young shoots and unopened flower buds are steamed and eaten as vegetables.

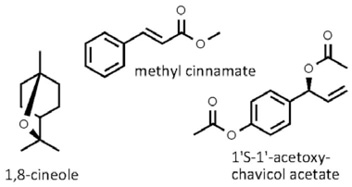

FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS Essential oil and several unusual chemical compounds contribute the strong flavour of galangal.3 The main components of the essential oil are reported to be 1,8-cineole, β-pinene, myrcene, chavicol and methyl cinnamate, while the pungent taste is due to 1’S-1’-acetoxychavicol acetate and several isomers4 which seem to occur in the plant as glycosides.

NOTES Galangal and related plants are widely used in Chinese, Indian and Indonesian traditional medicine and the dried rhizomes are nowadays freely available.

1. Burkill, I.H. 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula, Vol. 2, pp. 1327–1332. Crown Agents for the Colonies, London.

2. Hu, S.-Y. 2005. Food plants of China. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.

3. Harborne, J.B., Baxter, H. 2001. Chemical dictionary of economic plants. Wiley, New York.

4. Kubota, K., Someya, Y., Kurobayashi, Y., Kobayashi, A. 1999. Flavour characteristics and stereochemistry of the volatile constituents of greater galangal (Alpinia galanga Willd.). In: Shahidi, F., Ho, C.-T. (Eds), Flavour chemistry of ethnic foods, pp. 97–104. Springer, New York.