Murraya koenigii

Murraya koenigii

curry leaf

Back to “Culinary herbs: curry leaf (Murraya koenigii)*”

Murraya koenigii (L.) Spreng. (Rutaceae); kerrieblare (Afrikaans); ma jiao ye, ka li cai, duo ye jiu li xiang (Chinese); feuilles de curry (French); Curryblätter (German); karipatta, mitha neem (Hindi); duan kari (Indonesian, Malay); hojas de curry (Spanish); karivapilai, karuveppilei (Tamil); bai karee, hom khaek (Thai); lá cà ri (Vietnamese)

DESCRIPTION Pinnately compound leaves, with 8–12 pairs of lance-shaped, minutely gland-dotted and highly aromatic leaflets.

THE PLANT A small evergreen tree of 3–6 m (ca. 10–20 ft) in height. Small white flowers are borne in terminal clusters, followed by edible, single-seeded, fleshy fruits that turn red and then black when they ripen.1 Curry leaf should not be confused with the unrelated European curry plant (Helichrysum italicum), that is rarely also used as a culinary herb.2

ORIGIN Sri Lanka and India, where it is an important part of the culinary (and medicinal) traditions. It has been introduced to many other parts of the world by Indian immigrants over the last few centuries. It is commonly found in many kitchen gardens, supplying fresh leaves for daily culinary use, especially to flavour curry.

CULTIVATION Trees are most easily propagated from root suckers that typically develop around the trees but can also be grown from seeds or root cuttings. As an understorey shrub1 it is best grown in partial shade, with a few hours of morning sun and shade in the afternoon. Mature plants can withstand light frost but in cold areas it is better to grow the plant in a large container that can be taken indoors in winter.

HARVESTING Fresh leaves are mostly sold on local markets or the dried individual leaflets (with leaf rachis removed) are packed as a spice. The dried or powdered leaflets are considered inferior because they lose much of their flavour upon drying.2

CULINARY USES Curry leaf is an indispensable ingredient of Indian dishes. It has also become popular in Thailand, Malaysia3 and Indonesia (for fish curries and other dishes), as well as in South Africa and Réunion.2 Curry leaf is often roasted (toasted) in a little oil to release the flavours.2 Garam masala and sambar podi are two examples of “curry powders”2 that typically contain cumin, pepper and/or chilli pepper as main ingredients, but usually also fenugreek, turmeric, brown mustard, cardamom, cloves, coriander, ginger and tamarind. Curry leaves are essential for making sambar, a traditional pigeon pea and lentil stew. Sambar powder is made from pan-roasted spices (coriander, chilli, fenugreek, pepper, brown mustard and others), combined with cilantro and curry leaves.

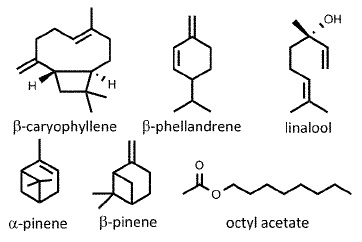

FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS The flavour is due to essential oil that varies from region to region. β-Caryophyllene, β-phellandrene, α-pinene and β-pinene are usually amongst the major compounds,4 as are linalool (floral and spicy odour, released after enzymatic hydrolysis)5 and octyl acetate (fruity odour, apparently lost during steam distillation).5

NOTES “Curry” as we know it today is a British concept based on the Tamil word kari (meaning “sauce”) and is now loosely applied to a wide range of spicy dishes.2

1. Parmar, C., Kaushal, M.K. 1982. Murraya koenigii. pp. 45–48. In: Wild Fruits. Kalyani Publishers, New Delhi.

2. Gernot Katzer’s Spice Pages (http://gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com).

3. Hutton, W. 1997. Tropical herbs and spices. Periplus Editions, Singapore.

4. Raina, V.K., Lal, R.K., Tripathi, S., Khan, M., Syamasundar, K.V., Srivastava, S.K. 2002. Essential oil composition of genetically diverse stocks of Murraya koenigii from India. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 17: 144–146.

5. Padmakumari, K.P. 2008. Free and glycosidically bound volatiles in curry leaves (Murraya koenigii) (L.) Spreng. Journal of Essential Oil Research 20: 479–481.