Myrrhis odorata

Myrrhis odorata

cicely • sweet cicely

Back to “Salad herbs and herb mixtures: sweet cicely (Myrrhis odorata)”

Back to “Culinary herbs: sweet cicely (Myrrhis odorata)”

Back to “Spices: sweet cicely (Myrrhis odorata)fri”

Myrrhis odorata (L.) Scop. (Apiaceae); mirrekerwel (Afrikaans); cerfeuil odorant, cerfeuil musqué (French); Süßdolde, Myrrhenkerbel (German); finocchio dei boschi, cerfoglio di spagna (Italian); suito-shiseri (Japanese); sisilli (Korean); Spansk körvel (Swedish)

DESCRIPTION The leaves are pinnately compound, dentate and pale green. The small dry fruits are oblong, slender, up to 25 mm (1 in.) long, narrowly beaked and dark glossy brown when ripe. Both the leaves and fruits have a strong fragrance and aroma reminiscent of anise and liquorice.

THE PLANT A robust, aromatic, herbaceous perennial of up to 1.5 m (5 ft) in height. It has erect, grooved, hairy stems and bears small white flowers in compound umbels. As suggested by common names such as Spanish chervil, anise chervil and sweet chervil, the plant is superficially very similar to chervil (Anthriscus cerefolium) but differs in the large, fern-like leaves, the dark brown fruits and the sweet aroma. Sweet cicely is also known as garden myrrh. The term “myrrh” refers to aromatic resins, the most famous of which is collected as an exudate from the bark of East African myrrh trees (Commiphora myrrha) that grows in Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia. Another type of myrrh is obtained by boiling the branches of the eastern Mediterranean myrrh shrub (Cistus creticus) in water and skimming off the aromatic resin. This plant is believed to be the biblical “myrrh”.1

ORIGIN The plant is indigenous to central and southern Europe.1 It has a long history of use as potherb and for strewing on medieval church floors.1 This attractive and fragrant herb is now naturalized in most parts of Europe, where it is occasionally wild-harvested but also commonly grown in herb gardens.

CULTIVATION Plants are propagated from seeds or by dividing the rootstock of mature specimens. They are cold-tolerant and grow well in Scandinavia and other cold regions.

HARVESTING Leaves and stems are used fresh, while young fruits are picked when still green, before they become fibrous. Both leaves and fruits can be successfully dried for later use.

CULINARY USES Leaves, stems and fruits are used as a culinary herb to give a delicious, sweet, aniseed or liquorice taste to vegetable dishes, salads, soups, omelettes, stewed fruits, drinks and liqueurs. The fruits can be used to give a sweet spicy taste to meat dishes. Due to the natural sweetness of the herb it is used in rhubarb and stewed fruit dishes to reduce the acidity.2 The roots were once eaten as a vegetable.2

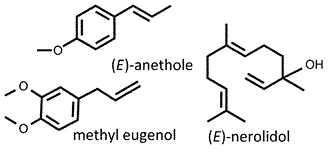

FLAVOUR COMPOUNDS The leaves and fruits contain an essential oil rich in (E)-anethole as dominant compound, accompanied by small amounts of methyl eugenol and (E)-nerolidol.3,4

NOTES The sweet taste of culinary herbs and spices such as basil, fennel and star anise is not due to sugars but to the presence of high concentrations of one or both of two common phenylpropanoids, (E)-anethole (also refered to as trans-anethole) and estragole.5

1. Mabberley, D.J. 2008. Mabberley’s plant-book (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

2. Kiple, K.F., Ornelas, K.C. (Eds), 2000. The Cambridge world history of food. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

3. Uusitalo, J.S., Jalonen, J.E., Aflatuni, A., Luoma, S.L. 1999. Essential leaf oil composition of Myrrhis odorata (L.) Scop. grown in Finland. Journal of Essential Oil Research 11: 423–425.

4. Dobravalskytė, D., Venskutonis, P.R., Zebib, B., Merah, O., Talou, T. 2013. Essential oil composition of Myrrhis odorata (L.) Scop. leaves grown in Lithuania and France. Journal of Essential Oil Research 25: 44–48.

5. Hussain, R.A., Poveda, L.J., Pezzuto, J.M., Soejarto, D.D., Kinghorn, A.D. 1990. Sweetening agents of plant origin: Phenylpropanoid constituents of seven sweet-tasting plants. Economic Botany 44: 174–182.