Chegwin Toffle’s curly blond hair was almost as wild as his imagination. His frizzy locks pointed in every direction imaginable, giving the impression he never combed his hair at all. This, in fact, was entirely untrue – he took great care to style it that way every morning.

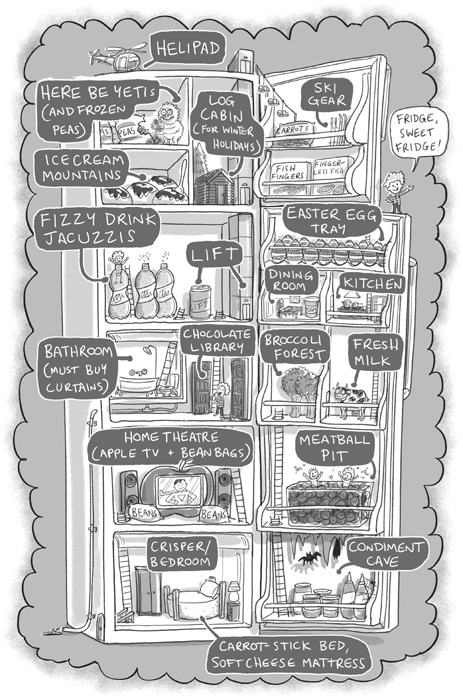

As a ten-year-old who loved to daydream, it would be fair to assume that Chegwin was like most other children his age. What set him apart, however, was the intensity of his thoughts. The entire world around him would fade away as a single idea took over. If he found himself wondering what it would be like to live inside a giant refrigerator, it would distract him from something as dangerous as an oncoming freight train. Which was happening now. But the freight train was his teacher.

Mr Bridges stormed towards Chegwin, who was sitting in his usual seat at the back of the classroom. ‘Well, Toffle? What’s the answer to my question?’

Chegwin was too busy imagining his bedroom in the vegetable crisper to notice the looming threat.

‘Toffle, answer my question immediately!’ Mr Bridges was close to throwing something at the boy. A pencil case, perhaps. Maybe a textbook. Or even better still – himself.

‘Toffle!’ The teacher slammed his chunky fists on Chegwin’s desk. ‘Pay attention!’

The thud put an immediate end to the boy’s daydream. Which was a shame, thought Chegwin, because he was just about to arrange his dining room in the dairy compartment. This would have given him easy access to his favourite snack – raspberry yoghurt.

‘Are you listening?’ demanded the teacher. ‘I’ve been reading aloud from this textbook for the last hour. It’s important to know about the history of cardboard boxes. Fascinating stuff.’

Mr Bridges was a plump man, whose high blood pressure had permanently turned his face the colour of grilled tomato. He was infamous for his short fuse, particularly when it came to students as apparently absent-minded as Chegwin.

‘Toffle, I’ve had it up to here with you,’ he spat. ‘All you do is stare out the window and imagine ridiculousness! You’re so far removed from the real world that you may as well be living in outer space. Dreamers like you never get anywhere in life. Grow a brain and pay attention for once!’

This upset Chegwin terribly, because he was concentrating. Mr Bridges didn’t seem to appreciate the effort it took to build stairs between the egg tray and door shelf. Not to mention the difficulty of plumbing the bathroom in the meat keeper.

‘I’m very sorry, Mr Bridges, sir, I –’

‘Be quiet! I haven’t finished berating you!’ Mr Bridges’ face scrunched up so much that he could have been mistaken for a bulldog, which had very nearly happened once in a restaurant when the waiter confused the angry teacher for a runaway pug.

As Mr Bridge’s face grew redder and redder, Chegwin could feel himself shrinking in his chair. The eyes of his classmates – who were tired of him getting into trouble – bore holes in his skin.

Mr Bridges stepped back and took a few quick breaths. Scolding his least favourite student had evidently puffed him out. ‘School is not for you,’ he said bluntly. ‘I don’t care if you turn up to class anymore. But if you do, I’m not going to waste my time trying to get through to you. You’re unteachable and you’ll never amount to anything.’

The afternoon bell rang, saving Chegwin from more of his teacher’s onslaught. Though the pain didn’t end there. His frustrated classmates elbowed him as they spilled into the corridor.

‘Wake up, lazybones. Stop dreaming.’

‘You’re a waste of space, Chegwin. You always put Mr Bridges in a bad mood.’

‘Why can’t you pretend to listen like the rest of us?’

‘You’re nothing but a fantasist.’

‘Fantasist. Nice vocabulary, Ralph.’

‘Thanks, Sienna.’

Chegwin was hurt by the comments and he walked home feeling glum that afternoon. No matter how hard he tried at school, he couldn’t seem to do anything right. The classroom was not for him.

He was so wrapped up in misery that he almost forgot to pick a flower for his mother. He leaned over Mrs Flibbernut’s white picket fence and selected a purple tulip. At least flowers couldn’t give insults.

Chegwin opened Mrs Flibbernut’s letterbox and slid some money inside. It was much more than the flower was worth, but he knew old Mrs Flibbernut was saving for a holiday. Her husband had passed away, and she needed a change of scene.

While many people in the neighbourhood sympathised with Mrs Flibbernut’s situation, it was only the Toffles who took a practical approach to helping her. Chegwin’s father had increased his son’s pocket money, instructing him to think of a useful way to encourage the old lady. So, thinking outside the box as only he could, Chegwin had arranged to buy flowers from Mrs Flibbernut’s front yard and give them to his mother. That way, he could help Mrs Flibbernut save for her holiday and, at the same time, put Mrs Toffle in a good mood. His mother’s high spirits would no doubt rub off on his father, increasing the boy’s chances of another pocket money raise.

This was how Chegwin’s mind operated. Beneath the blond curls and behind the chocolate-brown eyes worked the brain of a genius. Only nobody apart from Chegwin’s parents knew his true potential, because he was always drifting off in class.

The knot in Chegwin’s stomach tightened as he remembered Mr Bridges’ crimson face. He had never meant to get in so much strife. He always tried hard to be polite and pay attention, but he simply couldn’t help it if a new idea popped into his head. Perhaps Mr Bridges was right. Dreamers like him were never destined to amount to anything.

Chegwin’s mood changed when he arrived home. The front door was wide open – which it never was – and his parents sat on the edge of the sofa as though they were waiting for him. Judging by their faces, he couldn’t tell if someone had died, or if they had won the lottery. In the end, it turned out to be a bit of both.

‘Take a seat, son … whenever you’re ready …’ said Mr Toffle, tapping the sofa next to him. As a dreamer himself, he had learned the best way to get through to his son was by being patient. Chegwin had always appreciated this, so he gave his mother the tulip and sat down.

‘It’s a lovely flower, pumpkin,’ said Mrs Toffle sweetly. ‘It looks delicious.’

‘Huh?’ Chegwin’s mouth popped open like a goldfish. ‘Did you just say delicious?’

Mrs Toffle quickly put down the tulip. ‘Of course not, muffin … Perhaps you imagined it.’

She had him here. Sometimes the imaginative side of Chegwin’s brain was so excitable that the lines between reality and fantasy blurred. The logical side of his brain was forced to concede. ‘But I thought you said … never mind.’

Mr Toffle picked at a loose thread on his T-shirt. It was a concert souvenir from one of the bands he managed – Screeching Green Lorikeets on Bicycles. ‘I’ll get straight to the point, son. Some important mail arrived for you today …’

Suddenly Chegwin was imagining himself being delivered by letter. If the envelope was large enough – and with lots of soft padding – it could be quite a comfortable ride. It would also be a lot cheaper to post yourself to a holiday destination, rather than pay for a regular flight. There was a business idea in something like this. Maybe he could test it out on himself next school holidays by using an old mattress and –

‘Chegwin, honey, are you listening?’ said his mother. Her gentle tone brought him back. Though she never raised it, there was something about her soft voice that got through to her son more often than not.

‘As I was saying,’ said Mr Toffle patiently, ‘although this is an enormous decision, your mother and I think we should honour the letter and let you choose …’

Chegwin spotted his afternoon tea on the kitchen bench: an apple and a muesli bar. He wondered what it would taste like if he ate them both at the same time. Probably quite nice. He’d have to cut the apple into tiny pieces and –

‘So what do you think, son?’ said Mr Toffle.

Chegwin refocused. ‘What were you saying?’

Mrs Toffle ran her hand through Chegwin’s blond hair. It was the same colour as hers, though much curlier. The twists came from his father’s side of the family. ‘Were you thinking about something else, cutie pie?’

Chegwin nodded.

‘Now pay close attention,’ said Mr Toffle, who had almost drifted off himself brainstorming band names. He leaned over and gently held his son’s head between his hands. ‘Something important has happened. A letter arrived for you, and a big decision must be made … It’s taken your mother and me by surprise, but we trust you will make the right choice.’

‘What’s going on?’ said Chegwin, who was now not only focused but utterly intrigued.

Mr Toffle blinked once, then delivered some news that would change his son’s life. ‘You just inherited a hotel.’