After a rocket-fuelled, pottery-smashing and secret-packed few weeks at Toffle Towers, Chegwin’s life began to fall into a routine. His mornings were spent ordering supplies for the renovations, sorting bills and chatting to guests as they checked out. He wanted to learn how to improve the business. What struck him most about the feedback was the power children had over their parents.

‘Daisy was so excited about the flying shuttle bus, we booked for two nights.’

‘Little Xavier wouldn’t shut up about having a chocolate milkshake bath. So we cancelled our booking at the Braxton Hotel and came here instead.’

‘Our kids loved the stay. We’ll be back for the Great River Race.’

‘Excuse me? Are you listening, young man? Your eyes are glazed over.’

Chegwin – when he wasn’t drifting off – made notes after these conversations with guests, which he read over in his office until Mrs Flibbernut arrived for their morning lesson. He also kept the slide of his lookalike in the top drawer and held it to the light from time to time. Who was the boy in the photo?

Mrs Flibbernut was proving to be an excellent teacher. She tailored their lessons and made things so interesting that Chegwin found it almost impossible to tune out. The only occasion he managed to drift off was when she was explaining how rock climbers use belay and rappel devices to descend steep rock faces. His mind kept randomly imagining what scuba diving with dolphins in Sydney Harbour would be like.

Mrs Flibbernut taught him – through improvised dramatisations fuelled by her double-shot espressos – about advertising, the benefits of keeping databases, how investments work and how to maximise profits. ‘Growth will steady up long-term security,’ she said, climbing on top of the filing cabinet. ‘You need more bookings.’

Chegwin, of course, already knew this, but the numbers took on a whole new meaning when Mrs Flibbernut explained things. He decided to tell her about the money that had gone towards the restaurant idea.

‘I had to do something. The hotel would die a slow death otherwise. I don’t want anybody to lose their job.’

‘It’s risky,’ said Mrs Flibbernut, ‘but it’s one of those investments I was telling you about. The rewards could be high. Then again, you could be out of business tomorrow.’

Which was true. The current bookings were barely keeping the hotel afloat. Money was being sucked into the restaurant faster than it could be made.

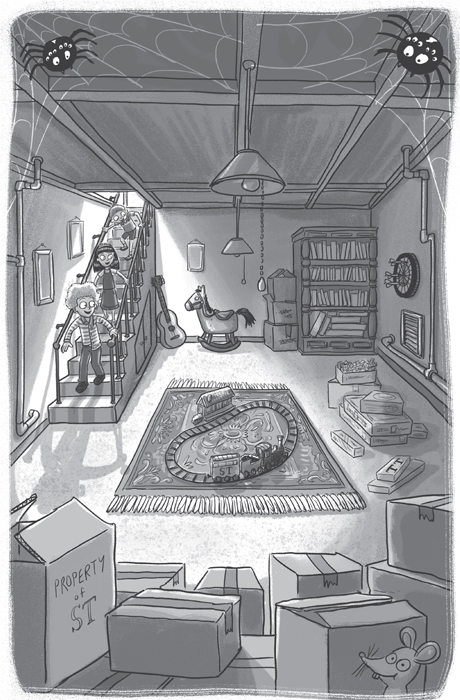

Chegwin’s favourite part of the day was the afternoon. That was when Amy and Rufus would meet him near the pile of garden pots behind the right wing. The trio would look around to make sure nobody was watching, then sneak into the storeroom with the slide projector. Chegwin had found the key to the small door in the corner which, when unlocked, opened onto a thin staircase that led down to the basement he’d seen on the hotel’s blueprints. It was the perfect hideout.

The basement was filled with an odd collection of old toys, dated but clearly loved. There was a rocking horse, a pile of board games, packs of cards, an electric train set and a box filled to the brim with dominoes.

‘Hours of entertainment,’ said Amy.

‘This board game has TT written on the top,’ said Rufus.

Chegwin examined the lid. ‘Terrence Toffle,’ he said. ‘It must have been his.’

‘Honk!’ said Doc.

Rufus waved a finger at the goose. ‘I’m warning you, Doc, not too much noise down here. This is our secret hideout.’

Doc lowered his head in submission and pecked at an empty box.

‘He can be very good when he has to be,’ said Rufus.

‘This train carriage has ST etched onto the side,’ said Amy. ‘I wonder who that might be?’

Chegwin remembered the photo of his lookalike. ‘I’m not sure …’

There was also an oak bookshelf positioned against the wall at the far end of the basement. There were dozens of books on the shelves with titles including ‘Hotel Management’ and ‘How to Dream a Better Life’. Scattered between these was a generous selection of fiction material.

‘The bookshelf matches the oak desk in my office,’ said Chegwin. ‘I wonder if it was cut from the same tree.’

‘We should start a book club,’ said Rufus.

The children enjoyed their afternoons in the basement. They tidied the toys, arranged the books in alphabetical order, carried three chairs down from the storeroom and straightened the old rug in the centre of the room. Chegwin even managed to find a large plastic tub for Doc. The children filled buckets with water and emptied them into the tub, giving Doc just enough water to paddle in.

‘I suppose this makes us friends,’ said Amy one particular afternoon, as she pulled the string to flick on the basement light globe.

Friends.

Both sides of Chegwin’s mind froze.

‘Did you hear that?’ said the logical side.

‘Did she just say friends?’ said the imaginative side.

‘She did! She did! She did!’

The two sides of Chegwin’s brain ran to give each other a hug, but collided with such happy force they nearly knocked each other out. As such, Chegwin could only manage a muddled response. ‘Bo-diddly do-bop-bop-ba-wow.’

‘Sometimes I’d kill to know what’s going on inside your head,’ said Amy.

Chegwin grinned. Having friends was a first for him.

‘Is there any food down here?’ said Rufus.

Amy laughed. ‘Trust you to be thinking about your stomach, pot pant.’ She turned to Chegwin. ‘I don’t know where he puts it. Eats like a horse but skinny as a rake.’

Chegwin was learning a lot about his new friends. Rufus’s parents ran one of the cafes that overlooked the river. They had named it after the family – The Corkindrop. Rufus was homeschooled so he could be on hand when things got busy.

‘A lot of kids in Alandale are taught at home,’ explained Amy. ‘The closest school is an hour away, so my dad doesn’t want me wasting all that time on the bus. He says kids should spend more time outside exploring.’

‘I like the sound of your dad,’ said Chegwin. ‘What does he do?’

‘When he’s not teaching me he works as a kitchenhand at the Braxton Hotel, but I don’t like it over there. It’s boring and too clean. And the lady who runs it is nasty. Toffle Towers is much nicer. It has character and hidden basements.’

‘And a squeaky floor,’ added Chegwin. ‘There’s a stair under the portrait in the lobby that goes bonkers if you tread on it the wrong way.’

Chegwin opened up about himself too. He told Amy and Rufus about how a letter had arrived out of the blue explaining that he was the inheritor of Toffle Towers. He told them how the hotel would have had to close if he hadn’t taken up the role of manager, and how badly he wanted the staff to keep their jobs. He shared how his parents had supported his decision to move to Alandale, and how betrayed he felt when he overheard their conversation.

‘Wait a tick, wait a tick,’ said Amy. ‘Are you telling me you’re ten years old and you only just found out that you have a brother?’

‘Yes.’

‘This is huge! We need to do some investigating.’

‘We do?’

Amy’s sharp green eyes flashed in the basement light. ‘We do.’

‘You can count me in,’ said Rufus. ‘Especially if there’s free food involved.’

‘What about Doc?’ said Chegwin.

‘He’ll be okay here,’ said Rufus. ‘He has enough water and food.’

Being careful not to be seen leaving the basement, the trio made their way over to the staffing quarters. As they crept along the main hallway, they could hear Dusty and Mildew talking inside one of the rooms. They had finished their housekeeping duties for the day and had resumed their game of Monopoly.

‘I’ll trade you Park Lane for Regent Street.’

‘Not happening.’

‘Old Kent for Vine Street.’

‘Throw in a hundred pounds and it’s a deal.’

Amy nodded thoughtfully. ‘UK edition.’

‘Which way to your parents’ room?’ whispered Rufus.

Chegwin pointed further down the hallway. ‘This way. But we’d better be careful. You don’t want to get on my mum’s bad side.’

Chegwin realised he was seeing less and less of his parents. He was never quite sure where or when he’d bump into them. Once, he was certain he’d seen them slip through one of the doors in the right wing. But when he went to explore, they were nowhere to be seen.

Amy tiptoed into their bedroom. ‘There’s gotta be some evidence of your brother in here somewhere.’

Chegwin didn’t like the thought of going through his parents’ belongings. They had always taught him to respect the privacy of others. Snooping around didn’t fit that bill.

Then again, neither did hiding the fact he had a brother.

‘Some of their photo albums arrived in the latest shipment from storage,’ suggested Chegwin, pointing to a bookshelf. ‘I’ve never thought to look through them but we could start there.’

Crash.

‘Rufus!’ hissed Amy. ‘Don’t be a pot pant!’

The red-haired boy had knocked over a vase.

Chegwin froze. Had the noise been heard? He strained his ears to listen.

Dusty’s voice echoed down the hallway. ‘Blast it! Do not pass Go. Do not collect two-hundred pounds …’

They were safe for now.

Amy took down one of the photo albums from the shelf. ‘You’d better clean that mess, Rufus.’

Chegwin peered over Amy’s shoulder as she flicked through the pictures. ‘That’s a photo of me taking my first steps,’ he said.

‘Your hair hasn’t changed a bit.’

‘I like it that way.’

‘Me too. It suits you.’ Amy flicked backwards to the first page of the album and gasped. ‘There are pictures missing.’ She passed the book to Chegwin.

It was true. Three photos had been removed from the first page. He could tell because there were small glue stains left behind. There were also three short captions above where each photo had been placed.

‘Hello, Milton.’

‘Milton’s first wave.’

‘Our little boy is growing.’

‘Milton must be your brother,’ Amy whispered. ‘What’s on the next page?’

But Chegwin wasn’t listening. He had drifted off in thought and was wondering what it would be like to be a cloud. Did a cloud experience emotion? It could drift over the land forever, searching for belonging, occasionally bumping into mountains or emptying its soul onto the parched earth below. If it became angry enough, it might produce bolts of electricity or hail or –

‘Ahem,’ said Amy. ‘Now is not the time to switch off. We have some serious detecting to do.’

‘Right, sorry,’ said Chegwin. He turned the page of the album to find a bunch of pictures of himself in a high chair. He was wearing a tiny beanie, though clumps of his blond curls poked out from underneath. ‘Looks like my first trip to the snow.’

A door creaked open from the other end of the staffing quarters and Mr Toffle’s voice travelled down the hall. ‘That’s why I married you, Mrs Toffle …’

‘My parents!’ squeaked Chegwin, his face turning white.

‘Quick,’ said Amy, ‘follow me.’

She opened the bedroom window and leapt outside. ‘Hurry up, you two.’

Rufus was next on the lawn. He landed with a clink, his pockets bulging with the broken pieces of vase that he had cleaned up while Amy and Chegwin looked at the photos.

Chegwin shoved the album back into its place and managed to escape just before his parents’ footsteps reached the door. He pulled the window closed and crouched on the grass next to his friends.

‘That was close,’ whispered Amy.

‘Too close,’ said Chegwin.

They quickly crawled to the far end of the quarters, then stood up once they had reached the safety of the forest. They stayed in the shadows of the trees until they neared the front of the hotel.

‘I need to head back home,’ said Rufus. ‘It’s getting late and I have to help clean up at the cafe.’

‘Yeah, I should go too,’ said Amy. ‘Dad will be back from the Braxton soon.’

Chegwin pointed to the Toffle Towers shuttle bus. ‘Feel like taking the aerial route?’

‘Yes, please!’

The young manager poked his head inside the lobby. ‘Lawrence, could you please pop to the work shed and ask Barry to shuttle my friends into town?’

‘Dear me,’ said Lawrence. ‘I’d prefer not to … My Saints beat his Tigers again last night. He’ll be livid.’

The boy raised an eyebrow.

‘As you wish, Master Chegwin,’ said the butler with a sigh.

Chegwin watched with interest as Barry fired up the bus. He waved goodbye to his friends, then gave a big thumbs up to Lawrence, who was clinging for dear life to the roof of the shuttle, his top hat still perfectly straight.

Earlier, the butler had collected Barry from his work shed and delivered him to the young manager. But Barry, never one to miss an opportunity, had wrestled Lawrence into a magnetic mesh suit and hoisted him onto the roof of the bus. It was revenge for his football team’s loss.

The butler was now stuck tight and the shuttle was preparing to take off.

Chegwin had seen Barry test the mesh shirt on a dummy earlier that day and knew it was perfectly safe. The magnets were so strong that Lawrence was in no danger of being blown away. This would be the final test in a series of important experiments that now signalled a green light for Chegwin. He could officially launch his restaurant idea.

The bus disappeared – along with Lawrence’s shrieks and cries – into the afternoon sky. Chegwin returned to his office to tidy up some paperwork.

Ding.

Somebody had pressed the bell in the lobby.

Chegwin walked out to the reception desk, where he found a woman dressed in a long fur coat that appeared to be made from bear skin. She wore several gold chains around her neck and was frowning.

‘Welcome to Toffle Towers,’ said Chegwin. ‘I’m the manager. How can I help you this evening?’

‘So, it’s true,’ said the lady with a sniff. Her voice was deep and purposeful. ‘A child is in charge.’

Chegwin couldn’t help but stare at her eyebrows, which were two of the bushiest brows he’d ever seen. He had a strange urge to reach out and tickle them, but the woman’s dark eyes told him that nobody dared take her lightly.

‘My name is Brontessa Braxton. I own the hotel on the other side of town.’

The boy offered his hand. ‘Chegwin Toffle. Pleased to meet you.’

Brontessa turned away without shaking his hand. ‘I’ll be keeping an eye on you, Chegwin.’ And with that, she disappeared outside.