CHAPTER 1

Finding the Life We Lost in Living: Understanding Inner Bonding

It is difficult indeed to struggle against what one has been taught. The child’s mind is a helpless one, pliable, absorbing. It makes what it learns a part of its very nature…. Yet…you must change your minds, you must renew your hearts, and you must do it alone. There are no teachers for you.

To My Daughters with Love

PEARL S. BUCK

You’ve achieved everything you’ve ever thought would make you happy, but the gnawing, empty feeling that something is missing is still there. To paraphrase Rabbi Harold Kushner, you’ve discovered that “all you’ve ever wanted isn’t enough.”

You may feel lost, out of touch with yourself and others, in an emotional fog much of the time. You often feel as if you’re doing nothing more than going through the motions. You may agonize over feeling insecure, inadequate, unlovable, and alone.

These are deeply painful feelings, pervasive and persistent—so painful, in fact, you may have discovered any number of dysfunctional ways to ignore, deny, cover up, or numb the ache of your emptiness: alcohol, food, work, TV, sex, drugs, all of the above. Then one day something happens, a traumatic experience or an internal shift. You reach a turning point and ask yourself, as Jeremiah Abrams states in Reclaiming the Inner Child, “Where is the life we lost in living?”1

Certainly you’re not alone with these kinds of feelings. Most of us struggle with continuous or periodically recurring emotional pain for significant portions of our lives. This happens either because we don’t know another, better way, or because we’re unwilling to try, afraid we’ll only make matters worse. Unfortunately the pain often has to become intolerable, or a crisis must force the issue, before we take action on our own behalf. Take the case of Tom, for example.

Tom had never been in a therapist’s office and he wasn’t happy about being there now. He sat stiffly in his dark blue suit, unaware that his fist was clenched and his expression stern. He would never have come at all, but the CEO of his company took him aside last week and told him that his outbursts of temper were undermining employee morale and driving potential customers away. “Get some help,” the CEO told him. Frustrated and angry, but seeing no other choice, Tom made an appointment.

After we talked for a while about Tom’s stress level and work load, I said, “It sounds like you’re not taking very good care of yourself.”

“Take care of myself? That’s not realistic. I have too much to do!”

“But you fly into unpredictable rages, and you could lose your job because of that. And being so stressed out, you’re likely to lose your health as well. Can you really afford not to take care of yourself?”

“I don’t think I can,” he said softly. “I don’t know how.”

Tom was telling the truth. He didn’t know how; he’d never learned. He had been “at work” since early childhood. His father was an abusive alcoholic, so Tom’s earliest memories were of trying to protect his mother and sister from harm. When he realized his father treated them better when he wasn’t around, Tom left home and lived on his own. He was fifteen.

Most of us don’t grow up in these extreme circumstances; but even in the best possible beginnings, very few of us know what it looks like to take care of ourselves. We haven’t seen that kind of behavior anywhere—not in our families, not even on TV. So we follow the patterns we’ve learned, and we let ourselves down because we don’t know what it looks like to be loving to ourselves as well as to those around us. We abuse ourselves, ignore or deny our pain—all because we don’t know what else to do. We desperately need to begin to think about these questions: “How do we take care of ourselves? How do we make ourselves happy? How do we bring joy into our lives?”

Take Sandy, for example. Sandy is a divorced mother of two young daughters, a third-grade teacher. Long hours of preparation have paid off—her students love her, their parents praise her, and the principal has commended her in glowing written evaluations. Practically the only one who isn’t convinced that she is a competent, worthy, lovable person is Sandy herself. Constantly exhausted, nagged by indecisiveness and depression, she’s discounted everything she’s accomplished, including others’ affirmations. The only reason Sandy entered therapy was for her daughters. She was determined that they wouldn’t suffer the way she had.

In therapy sessions Sandy said bluntly that she rejected others’ loving support “because I don’t deserve it.” When asked, “Why do you drive yourself so hard? Why don’t you take better care of yourself?” she answered, “Because selves aren’t for taking care of.”

Where do beliefs like this come from? Why does Sandy believe that she doesn’t deserve love? After all, if she did, she’d take care of herself. She loves her daughters and takes great care of them, making sure they eat right, rest enough, and so on. Sandy values her car. If it’s not running well, she gets it fixed. Sandy is no different than any of us: We all take care of whatever we value.

How, then, can we learn to value ourselves so that we can become loving to ourselves, as well as to others? That’s what this book is about. It’s about Tom and Sandy and the multitudes of others who have absorbed or assumed the false beliefs and self-defeating attitudes and behaviors they saw in their childhood years. Because that’s what they have believed in and unwittingly copied, they have limited the potential for joy and love and fun in their lives. The purpose of this book is to teach all of us, each with our different pasts and present circumstances, another way of being in the world—a freer way of loving and living than the one we have known. That’s the promise and the power of Inner Bonding.

Inner Bonding is about giving ourselves, each and every moment, what we never had—or never learned—as children. It is about developing a loving relationship between our Adult and our Inner Child, a relationship that takes care of our Selves when we are around others and when we are alone.

What Is Inner Bonding?

Inner Bonding is a process of connecting our Adult thoughts with our instinctual gut feelings, the feelings of our “Inner Child,” so that we can live free of conflict within ourselves. Inner conflict is any kind of upsetting difference between our thoughts—what we think we should do or feel—and our feelings—our gut-level emotions and attitudes. When the conflict isn’t resolved—that is, when we go ahead and take action without regard for our feelings, or take action that is opposed to what we feel, or take no action in response to our feelings—then we’ve abandoned our feelings or disconnected from them. This disconnection creates the inner turmoil, the unrest we experience as discontentment and unhappiness.

The incredibly good news is that what has been disconnected can be reconnected, and with reconnection comes healing and wholeness. The power of Inner Bonding is the power of love as the force that heals, love from Inner Adult to Inner Child. Others’ love can support this process—love from mate to mate, from friend to friend, from therapist to client; but it is only when the Inner Adult loves the Inner Child that true healing and joy occur.

It would be ideal if our thoughts and feelings could be connected at all times. Although we cannot expect this state of perfection, we can learn the Inner Bonding process by practicing it until it becomes internalized, an automatic part of our thinking and feeling processes. To learn the process most effectively, we need to understand more about how we function, both internally and externally.

To begin with, the Adult aspect of our personality is our external aspect, the part of us that is able to take action in the world. Inner Bonding requires our Adult to be in conscious contact or connected with our inner, natural self, the vulnerable, feelings-driven self, referred to as the Inner Child. When our Inner Adult is connected to our Inner Child, that is Inner Bonding. When our rational and emotional aspects are connected in this way, we don’t feel internal conflict, because there isn’t any. Free of inner conflict, we feel peaceful, open to joy, and open to giving and receiving love.

Knowing how to initiate this connection is part of what we need to learn. This book hopes to teach that in two different ways: (1) by describing the actual dynamics of the process of Inner Bonding; and (2) by demonstrating Inner Bonding in action, providing examples of people in specific situations and relationships, so you can watch and learn from their individual bonding process.

Before we define the integral, working parts of Inner Bonding, let’s get an overview of the Inner Bonding process as a whole. This will also give you an idea of the process and the goal—in terms of your own internal state of peacefulness or ease, and in terms of your loving relationships with others.

Inner Bonding in Action, An Overview

On the simplest level, the first step to Inner Bonding is to become aware of your inner discomfort, “dis-ease,” or conflict. The second step is to acknowledge that you have a choice, one that only you can make, to ignore your feelings or to heed them: You have to choose whether you are going to be closed to your feelings or open to them. The third step is to recognize that, whether closed or open, either choice you make has consequences. This means that if you choose to be closed, you are also choosing the negative consequences of being closed. If you choose to be open, you are choosing the positive consequences resulting from your openness. You can’t choose to be closed and realistically expect the consequences of being open.

With just that much as a basis for understanding the process, let’s look at Inner Bonding in action with the example of Tom.

The Case of Tom

This was Tom’s first experience with therapy. He was resistant to the process and a beginner in terms of examining his own feelings. We already know that he is a high-achieving corporate executive, and that his father was an abusive alcoholic. Now let’s add that Tom has a wife and one son. No more personal history or context is needed to show what the consequences would be for each of the choices he can make: to be closed or to be open to the gut-level feelings of his Inner Child.

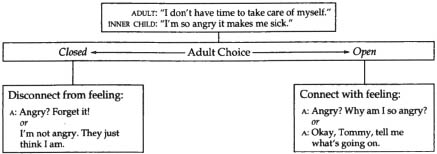

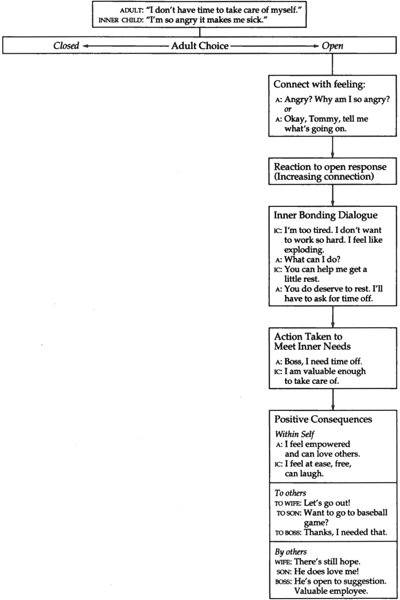

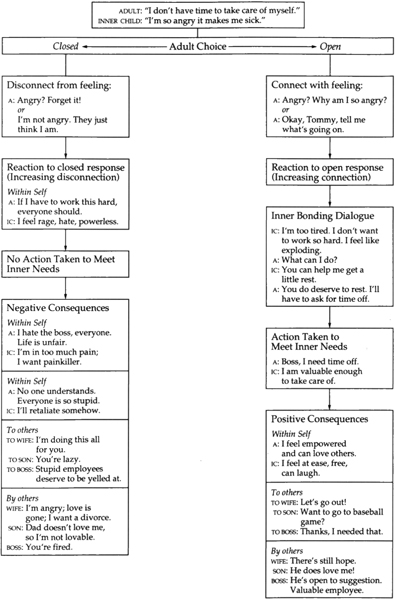

Tom’s internal and external dialogue is shown in diagram form in Figure 1. As you read, you’ll be aware that there are many other possible thoughts and feelings Tom could have had. However, what becomes strikingly clear is that once he makes his initial choice to be open or closed, the consequences that follow are unavoidable.

Figure 1. Tom’s Inner Conflict

Tom has stated the belief of his Inner Adult, that he has no time to take care of himself. He’s also realized that his gut feeling is anger. The thought of his Adult and the feeling of his Inner Child are in conflict. His choice is either to deny that this conflict exists or to acknowledge it. One of his options is to disconnect from the feeling, refusing to take responsibility for learning about it. His other option is to be open to the anger, connect with the feeling, and take responsibility for learning why he feels this way.

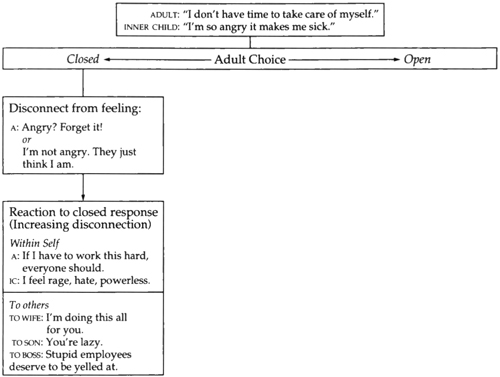

Figure 2. Tom’s Inner Conflict

Let’s assume that Tom decides to try to be “strong” and hide his feelings, even from himself. He chooses to disconnect from his anger by denying or repressing it. As the discomfort or pain escalates, the pressure builds. The disconnection between his Adult and his Inner Child increases, and he takes out his anger on those around him. Unloving to himself, he is increasingly unloving to others.

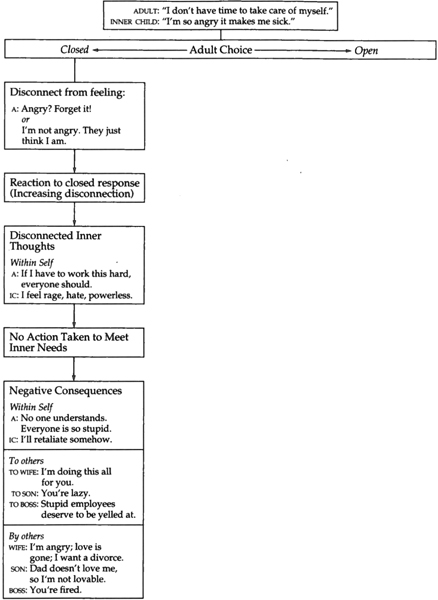

Figure 3. Tom’s Inner Conflict

As you can see, Tom’s choice to disconnect from his feeling and act in increasingly unloving ways is causing others to disconnect from him, a negative consequence of his choice to close to his feelings. The final blow in this scenario is that Tom is alone, separated from love within himself and from those who love him. Eventually the feelings of his Inner Child will find some kind of destructive release—addictions, stress-related illness, and so on.

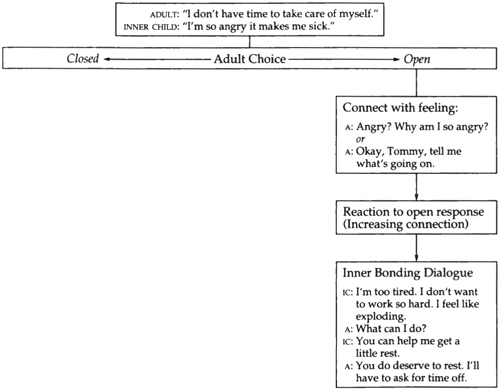

The picture changes dramatically if Tom chooses to connect with his feelings and to learn from them. Through the Inner Bonding dialogue process (described in detail in Chapter 2), he can focus his inner dialogue on the cause of the pain by asking what the Inner Child needs. This enables him to explore the options open to meet the needs of his Inner Child and relieve the cause of his anger, while meeting his Adult needs as well. Then he can know what action to take, based on that internal decision-making process.

Figure 4. Tom’s Inner Conflict

Once Tom takes the action, he experiences the positive consequences almost immediately. Tom feels more powerful, not less. He feels lighter and happier and eager to reestablish connection with those he loves. In this case Tom has not waited too long. His family is affirmed by the reconnection; and his boss has renewed faith in Tom’s qualities as a top employee when he sees Tom’s anger at others diminish.

Figure 5. Tom’s Inner Conflict

Figure 6. Tom’s Inner Conflict

When we see the total picture and contrast the positive and negative responses and consequences, some general conclusions are very clear:

1. When you are disconnected from your feelings, you act in disconnected ways to others, creating further disconnection from them and within yourself.

2. When you are disconnected from your inner self, or Inner Child, you can’t realistically expect the positive consequences that go with being connected to your feelings.

3. The choice to be open leads to greater inner power and more love of self and others. The choice to be closed leads to isolation and alienation between others and within yourself.

Tom’s case is just one specific example, but the dynamics are universal: Closed, unloving choices perpetuate closed, disconnected reactions and negative consequences. Open, loving choices initiate the chain reaction of open, connected, and positive consequences.

Now that you have seen the process overview, let’s define some terms and explain some dynamics. Before you go on you will need to know what I mean by the terms Inner Child, Inner Adult, and Loving Behavior.2

Who Is Your Inner Child?

The Inner Child is the aspect of our personality that is soft, vulnerable, and feelings-oriented—our “gut” instinct. It is who we are when we were born, our core self, our natural personality, with all its talent, instinct, intuition, and emotion. The Child is our right-brain or creative aspect of being, feeling, and experiencing. It’s the part of us that existed before we had experience. It is useful to refer to this aspect of our personality as a Child because it allows us to get a handle on those feelings and senses that existed before our maturing experiences merged or confused our impression of the two aspects of our personality, our Adult and our Inner Child.

To speak of an Inner Child is not to over-romanticize childhood. When we were very young we did many childish things—we talked baby talk, we played in the mud, we slapped our sisters and brothers when we were angry, we pouted or stomped our feet when we didn’t get our way.

Our Inner Child, however, is childlike—our vulnerability, intuitiveness, sense of wonder, imagination, innate wisdom, and ability to feel our feelings have not changed or aged with our growing, adult experience. Thus, while many of us had very unhappy childhoods, that doesn’t mean our inner nature is essentially unhappy.

Does Everyone Have an Inner Child?

We all have a vulnerable, intuitive, instinctual inner self. As psychiatrist Carl G. Jung said so well, “child” is only the means to express this psychic fact, the symbol of our preconscious nature:

The child motif represents not only something that existed in the distant past, but also something that exists now; that is to say, …a system functioning in the present whose purpose is to compensate or correct, in a meaningful manner, the inevitable one-sidedness and extravagances of the conscious mind.3

It is clear that we all do have an Inner Child. When people ask whether this can really be true, it usually reveals that they are not in touch with that soft and vulnerable part of their nature. When life is fairly easy and there are no major problems at hand, this lack of awareness is not a particular problem. But when there is conflict or a personal crisis and we feel unhappy or distressed, being out of touch or disconnected from our Inner Child can prevent us from restoring our emotional equilibrium.

One of my clients, Laura, was particularly resistant to the Inner Child concept, even though she understood that this was a just a label for her vulnerable, natural inner self. Eventually, however, a time of unusually high stress at work coincided with an emotionally difficult time at home, and she found herself getting more and more stuck. Instead of working faster, she was going slower. Instead of being able to think things through logically and find satisfactory solutions, she found herself getting more anxious and emotional, crying at unpredictable times.

Finally, when this state became unbearable, Laura had the following experience:

I was driving along one day, and I thought to myself, well, if I’m ever going to get with this “Inner Child” bit I may as well give it a try. So I said to myself, “If you [her Inner Child] are in there, speak up.” I was dumbfounded to hear a small voice within me say, “Help!”

In a flash of understanding—and this surprised me even more—I knew what that meant, and I said back to myself, as if to my Child, “You don’t have to do this work all alone.” And in the amount of time it took me to say those words, my stress level dropped so many degrees I could feel energy pouring back into by body.

I had absolutely no idea how helpless and overwhelmed I had been feeling—like a little girl left to do an adult’s work all alone. I was able to still feel myself as a child, watching my father so stressed out and irritable and miserable over all the endless work to be done, with never any time or permission to play. And when he’d kiss me goodnight, after he’d been working all day and I had been playing, he’d say, “But good hard work will make you feel better…” He was kind and loving to all of us kids, gentle and truly adoring. He meant so well and the message was so subtle. All four of us daughters learned it by heart: Play doesn’t make you feel good; hard work does. Now we’re all workaholics.

Who Is Your Inner Adult?

The Adult is the logical thinking part of us that has collected knowledge through our years of experience in the world. It is our intellect, our left-brain, logical, analytical, conscious mind. It is the part of us that is thought and action, as opposed to feeling and being, which are the realms of the Inner Child. The Adult is concerned with doing rather than being, with acting rather than experiencing.

The Adult is the choicemaker regarding intent and actions. It is always the Adult that chooses our actions, just as it is in a family. A young child cannot take actions on its own behalf—it cannot shop for food and cook the meals; it cannot earn the money to provide food and shelter, it cannot call a friend or therapist when in need of help. The Child within us cannot take these actions. Taking action on behalf of our Inner Child is the job of the Adult—taking care that our gut feelings and our thoughts are connected, synchronized, not in conflict. As we saw in Tom’s case, we can choose actions that are open and loving, or actions that are closed and unloving.

When we are born, we have no worldly, adult experience. But from the moment of birth, our Adult begins to develop. When we are two years old, our Adult is two, with two years of experience in the world. By the time we are three or four, we are doing many adult activities—choosing our own clothes, dressing ourselves, asking for help when we need it. The adult aspect is learning how to be an Adult all along from the adults in our environment. The Adult, then, is the aspect of our personality that is learned. One of the things we can learn is to be loving or unloving to our Inner Child.

What Is Loving Behavior?

Loving behavior is behavior that nurtures and supports our own and others’ emotional and spiritual growth. An inseparable part of this is taking responsibility for our own pain and joy. Therefore loving yourself means taking responsibility for healing pain—pain from the past and the present, for exploring and resolving self-limiting beliefs, and for discovering and taking action to bring about your joy.

Loving someone else means that you want for them what they want for themselves and that you support them in whatever they feel would bring them joy.

When we are being loving to our Inner Child, we are open to learning about our Child and from our Child. Loving our Child means choosing to learn about ourselves—our past and present pain, fears, and beliefs. Laura opened to learning about her Inner Child simply by saying, “If you’re in there, speak up!” She learned from her Inner Child when the self of her feelings cried out, “Help!”

At that point Laura’s Inner Adult again had the choice to be loving or unloving. If she had said, “Stop being so weak and feeling sorry for yourself!” the feelings of the Inner Child would not have been honored or validated as real and worthy of notice. The consequence of that choice would most likely have been that Laura continued to stay stuck with her pain, continued her unexplained crying spells and suffering. Instead she made the choice to acknowledge and learn from these feelings by connecting her present pain with ways of dealing with the world she had learned in the past. Through this connection she came to the conclusion, “That was my Child’s belief, but it’s not accurate. I am not a child having to do all the work alone. I am a grown-up woman with options for other ways. I am not stuck. I am not a child, alone and helpless, who must shoulder an adult’s burden.”

The reason for learning about your Inner Child and learning Inner Bonding Therapy, the reason for writing a book about all this, is not to explain how Laura, Tom, Sandy, and so many others like them had imperfect childhoods, or even learned incorrect lessons from the best possible parents. The reason was simply put by Laura, when she said, “My stress level dropped so fast I could feel energy pouring back into my body!” These words were the tools that freed up her energy, released her from her increasing unproductiveness and pain, and allowed her to function at her full potential.

That’s what Inner Bonding is all about: freeing ourselves from the false beliefs that create fear and shame. These false beliefs function as shackles, tethering us to inaccurate ways of thinking based on what we saw or what we assumed when we were too young to know any better. Free from false beliefs, we no longer feel the need to sacrifice ourselves in order to get the love we need. We can accept and love ourselves, and we are free to love each other.