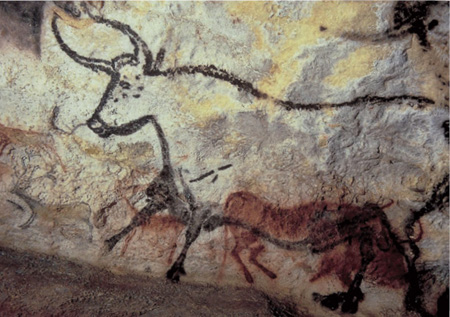

1 One of the large aurochs bulls that were painted in the Hall of the Bulls in Lascaux. The curious way in which the ear has been positioned is peculiar to Lascaux. A ‘broken’ sign has been placed on the animal’s forequarters. It is comparable to one of the signs in the Shaft (Plate 28); its repetition points to the conceptual unity of the cave.

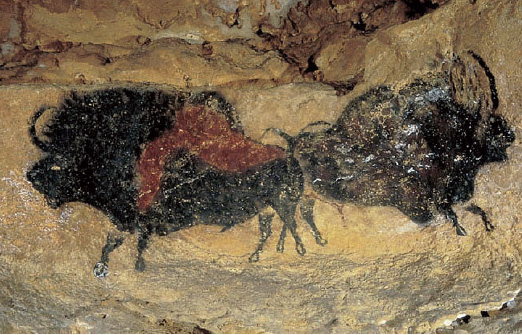

2 A curled-up bison painted on the ceiling of Altamira. The form of the animal has been ‘squeezed’ into the shape of a boss of rock that hangs down from the ceiling. There are others like it in Altamira. There was an interaction between the shape of the rock and the image-maker.

3 A delicate painting of a hind from the Altamira ceiling. Some researchers see a contrast between the strength of the bison and the sensitivity of the hind.

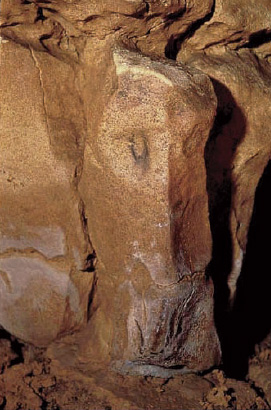

4 and 5 Two ‘masks’ painted in the Horse’s Tail, the deepest passage in Altamira. This is another instance of interaction between physical features of the cave and images. The two ‘masks’ seem to peer out of the wall as the visitor turns at the end of the passage and begins to leave the cave. It is hard to say if these are the faces of animals or human beings. Either way, they suggest mysterious ‘presences’ in the caves watching those who venture into the underworld.

6 The world’s oldest ‘art’ (77,000 years old) comes from Blombos Cave on the southern coast of South Africa. A regular pattern was engraved on the ground edge of a small piece of ochre. Researchers debate whether this important find suggests fully modern minds, language and symbolism at an unexpectedly early date.

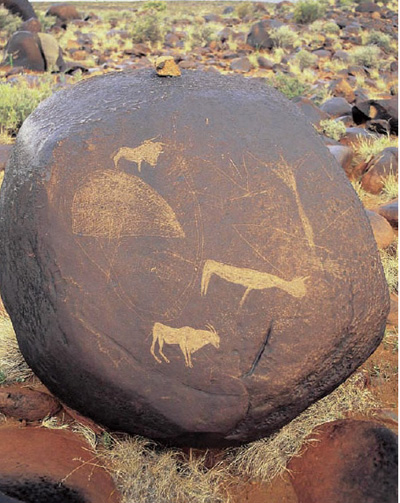

7 Rock engravings in the semi-arid Karoo, the part of southern Africa where Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd’s San teachers lived. These engravings were made by the ‘scratched’ technique.

8 A southern African San rock painting of an eland antelope. The image was made by the shaded polychrome technique that depicts the animal in remarkable detail. The eland was the San tricksterdeity’s favourite creature: it was a powerful, resonant symbol with many associations.

9 A southern African San polychrome rock painting of an antelope-headed figure that wears a white kaross (skin cloak). Note the blood falling from its nose; it indicates that the ‘being’ is a San shaman who has entered an altered state of consciousness and thus travelled to the spirit world where people assume animal features.

10 A piece of quartz lodged in a crack in a rock in Sally’s Rockshelter in the Mojave Desert, North America. Shamans believed that quartz contained a supernatural essence and afforded contact with the spirit world that lay behind the rock face.

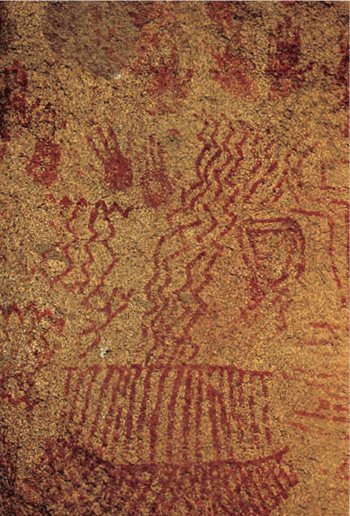

11 Rock art that was made as part of North American girls’ puberty rituals and found in southern California. The zigzags, closely associated with such rituals, probably derive from geometric imagery wired into the human brain and activated in altered states of consciousness. Researchers have found that shamans, who controlled altered states, supervised such rituals.

12 A painting of a bison in the Salon Noir, Niaux. It shows how Upper Palaeolithic images seem to ‘float’ on the walls of the underground chambers, an effect that is here enhanced by an absence of hoofs. Though a simple outline, the image catches the vast power of the bison.

13 A more detailed painting of a bison in the Salon Noir, Niaux. Here the sense of free ‘floating’ is suggested by the animal’s ‘hanging’ hoofs; it does not appear to be standing on the ground. Some researchers believe that such animals may be depicted lying on their sides, but the position of the tail and other features make this unlikely.

14 Finger-fluting in soft mud on the walls of the Cosquer Cave, the entrance to which was flooded when the level of the Mediterranean rose at the end of the Ice Age. People touched every part of the chamber’s walls, even above head height, and left these patterns in the malleable surface. Touching was clearly an important part of whatever rituals took place in the cave. An image of a horse was placed on top of the fluting.

15 An accretion on the wall of Le Portel has an anthropomorphic figure drawn around it so that the accretion becomes the figure’s erect penis. A similar instance a few metres away confirms that this use of the wall of the cave was not accidental.

16 A grid drawn with fingers in the mud around a natural hole in the wall of Hornos, Spain. It is as if the pattern is flowing out from behind the rock surface.

17 and 18 Light and shadow playing over a natural rock formation in the Salon Noir, Niaux, suggests the distinctive dorsal line of a bison in a vertical position.

19 The two Spotted Horses and surrounding hand prints in Pech Merle Cave. The head of the horse on the right is less realistic than the natural shape of the rock into which it is fitted. The lowest handprint suggests that the person was lying prone on the floor of the cave when it was made.

20 The so-called Unicorn (it actually has two horns) is the first major image in the Hall of the Bulls in Lascaux. Some researchers believe that the pendant belly suggests that the creature is pregnant. It has a number of oval shapes painted on its body. It is the first of a line of animals that face away from the entrance and towards the opening to the Axial Gallery.

21 The entrance to the Axial Gallery, Lascaux, is beneath the cavalcade of animals in the Hall of the Bulls. The opening can be seen straight ahead in this photograph. To reach the Axial Gallery, a visitor has to pass beneath, and almost through, the huge, impressive animals.

22 The Roaring Stag with its impressive antlers is on the right-hand wall, near the beginning of the Axial Gallery, Lascaux. The line of dots below the animal extends from a quadrilateral sign on the left to a jutting piece of rock on the right.

23 A tawny horse and dots to the left of the Roaring Stag in the Axial Gallery, Lascaux. The line of dots may be a continuation of those beneath the Roaring Stag (Plate 22). The image was made by the technique of blowing paint onto the wall of the cave.

24 Pieces of bone were thrust into cracks in Enlène, one of the Volp Caves. They suggest another Upper Palaeolithic way of ‘treating’ the meaningful walls of the caves.

25 A tooth of the now-extinct cave bear was placed in a niche in the Chamber of the Lion in the Les Trois Frères Cave, which leads off Enlène.

26 The Falling Horse is in the Meander at the end of the Axial Gallery, Lascaux. Curving around a pier of rock, it is one of the most striking images of Upper Palaeolithic art. Other images shown here include a horse on the far wall of the passage and, on the extreme right, the raised tail of a bison. Ochre-covered flint artefacts were found in a niche in the wall opposite the Falling Horse.

27 Two partly overlapping bison were painted in a natural hollow in the cave wall near the end of the Nave, Lascaux. The way in which they are painted and the curved surface suggest that the bison are coming out towards – and around – the viewer.

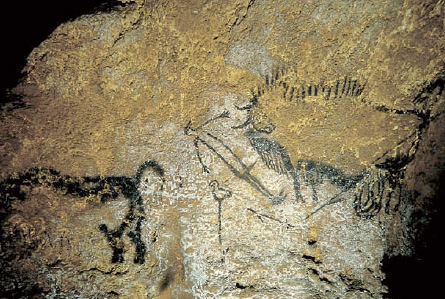

28 The images in the Shaft, Lascaux, are perhaps the best known and most debated Upper Palaeolithic cave paintings. Those shown here include a rhinoceros with raised tail, the outline figure of a man (the only one in Lascaux), a wounded bison and an outline bird on top of a staff.