Lost & Found

in Brazil

* * *

Thousands of miles away from New York on the island of Florianópolis, the only “benchmark” I care about is my conversational Portuguese. Well, that and my base tan.

I’m working on both at the beach across from my hotel, when a shadow falls across my dictionary.

Excuse me, a man says, kneeling down. I am a reporter with the Diário and I am making some stories on how people are spending December 21st. Today is the first day of summer in Brazil.

Yes, it is, I say, sitting up.

Can I interview you and take a few pictures, just as you are?

I’m wearing a bikini.

He’s wearing a press pass, which I examine before agreeing.

His English is marginally better than my Portuguese so we trade my dictionary back and forth, stringing together questions in English and answers in Portuguese: Where are you from? First time in Brazil? For how long here in Floripa?

The mutual humility of needing a book to communicate gives me the gumption to ask him for a word that isn’t in my dictionary. It’s a word that I may need to use while I’m here.

Do you know the word for a woman whose husband is dead?

Your husband? Dead?

Yes.

Viúva.

Viúva?

I hand him my Moleskine so he can write it.

I look at the word.

Accent on the “u,” he says, flicking his hand as though writing on air.

Accent on the “me,” indeed, I say.

He begins asking me about being a viúva and I don’t know how to say that was off the record in Portuguese so I wave my hand in a strike that gesture, but it’s too late: his pen is already flying and my mouth is already moving.

I feel completely stripped when the reporter turns the lens on me. My mind flashes to a movie scene of Aaron Eckhart as a widower being drilled by a photographer about his wife’s accident. He struggles to maintain poise for the camera while recounting the most emotionally vulnerable moment of his life. How awful, I’d thought. Where was his publicist during that shoot?

Where is my publicist during this shoot?

* * *

I’m in his story.

So is my picture.

But mercifully, the word viúva is not.

* * *

One of my PR accounts is an açaí company founded by two brothers who go to Brazil a few times a year. When they heard about my trip, they gave me some tips and introduced me via Facebook to their buddy who owns a sushi restaurant in Floripa.

Tonight, I meet their buddy, an alpha male who looks like Ryan Reynolds and has enough nervous energy to power a small city. I was not expecting to meet someone I might want to impress and sadly, I left that lip gloss at home. Halfway through appetizers, I realize I left my conversation skills at home too. I want to explain why I’m such an awkward dinner companion, but this fellow is tight with my clients and as per my CFO, I haven’t told them I’m widowed.

Thankfully, he’s so busy reading patrons’ body language and directing his staff that it’s easy to deflect any questions that may lead toward The Conversation. There are several moments—he asks why my camera still has photos from last Christmas and why I moved to New York from L.A.—when I could’ve explained why I don’t seem to know how to dine with a man and not act, as he puts it, pensive.

Before we part, he makes me promise I’ll go to Gravatá, his favorite beach, while I’m here.

It’s the best hike on the island and the trail is only a half-mile from your hotel, he said. Look, I’ll draw you a map.

I have no clue if this hike is for amateurs or pros, so today I place survivor-type things into my backpack and stop at the front desk.

I’m going to Gravatá, I explain. So if I’m not back by dark, please send a search party.

They laugh, wish me a good caminar, and I head down the road. I find the trail without incident, take a picture of the posted map in case I get lost, and head up the steep hill. The payday for my straining muscles comes a few hundred yards later, in the form of a 360-degree view of both the lagoon and the beach. It’s been a while since I hiked—Alberto wasn’t the outdoors type unless it involved ski-in-ski-out or beach service—and I feel high on endorphins and my “Dance Like No One’s Looking” playlist.

I shoot flora, mountains, boulders with succulents growing out of them—partly because they’re scenic and partly to sear these landmarks into my memory card so I know I’m on the right path when I hike out of here. I sprint down the last stretch of trail but halt at a shack that’s reminiscent of California’s Topanga Canyon: the front door is painted yellow, and nailed above it, there’s an orange highway marker with the number 1.

Beside the door is a panel spray-painted with the word BETO, one of Alberto’s nicknames. Seeing this word on the final landmark of my hike seems like a story no one will believe, so I shoot it before stripping down to my bikini and diving into the sea.

As I navigate back to the hotel, I’m aware of how far outside my comfort zone I am down here. I can feel myself shifting toward the girl I was pre-husband: scribbling in a Moleskine, getting around on more Spanish than I ever knew I had, enjoying the rush of endorphins on a hike, peeing behind a bush when there’s no restroom.

I’ve been out of touch with who I was before I moved to New York as a thirty-year-old bride. Marriage and Alberto and New York demanded a different version of me—much of it good, but some of it pretentious and Type A. Traveling alone seems to give me permission to shed what I don’t like, try on for size what I do, and figure the rest out as I go.

* * *

In Iguazu, I do something Alberto (and his acrophobia) would never do: take a helicopter ride. The South American jungle looks like a million broccoli florets and as we approach the huge moisture mass above the world’s largest cluster of waterfalls, I use the video-camera feature on Alberto’s camera. When I review the footage, I realize this is the first time I’ve filmed anything since last Christmas when I shot frozen waterfalls from our rental car in Quebec.

A year later, I’m as far from Canada as a girl can get and yet I am shooting waterfalls on Christmas Eve? Again? Does everything I do—consciously or un—return to him?

Back at the hotel, Christmas in Brazil is starting to feel like the worst idea ever. I’ve missed two calls from my parents, the wireless in my room isn’t working, and I’m so hungry, I’m hangry. I call downstairs for room service, but they can’t understand my Portuguese so they send someone up to take my order.

When I give the man my order, he shakes his head and finger and says no-no-no as if I were a toddler.

Por que no-no-no? I ask.

Porque it’s Noche Buena and they are only serving “special buffet” tonight. And only in the restaurant downstairs.

Besides, he says, we don’t deliver anything to rooms except what’s on the pool menu.

Of course not, I say, why would you serve the room menu in the room?

I shut the door in his face.

I’m at the wrong hotel, I say aloud.

In fact, I seem to be in the wrong country on the wrong day of the year and—

My voice is on the verge of a Christmas Eve meltdown, so I head to the bathroom to talk myself down from the ledge.

You’re tired, emotional, and hungry, Tré. But if you fix one of those things, you can get through tonight. So pull your hair back, put on some lipstick, and get some dinner already.

Downstairs, the Christmas buffet is crowded with cheery families celebrating Noche Buena. I take a deep breath and a small plate, working my way down the line of chafing dishes. Surprisingly, the salmon, rice, and julienne carrots don’t look half-bad. Or maybe I’m just that hungry.

Despite stares from my fellow guests and the confusion of staff trying to seat me, I carry my plate out of the restaurant and upstairs to my room, where I watch back-to-back episodes of Friends dubbed in Portuguese and fall asleep.

* * *

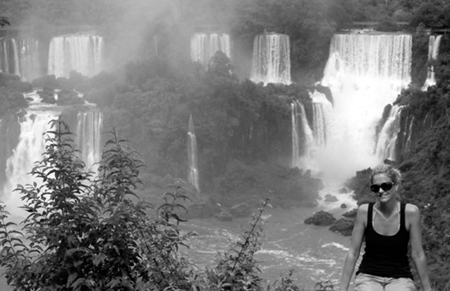

The edges of three Amazon countries converge in Iguazu, the world’s largest cluster of waterfalls. It is here that I’ve decided to spread Alberto’s ashes on Christmas Day, and it’s a body of water on a scale I’ve never seen, heard, or felt before.

Iguazu is louder than my grief, thicker than my loneliness, and its magnitude does exactly what it needs to do on December 25th: jolt me out of my pity party and into my rightful context in the world.

Or maybe the vodka I added to my morning coffee just took the edge off.

* * *

Six hours into my layover, even my noise-cancelling headphones, iPod, laptop, and phone can’t distract me from all the jolly couples everywhere. I’ve changed seats at least ten times, trying to distance myself from the intertwined hands and rounds of embraces. But I’m outnumbered. And tired of hauling my gadgets and luggage around in a lone game of musical chairs.

I give up.

The Christmas couples win.

* * *

Back in Florianópolis, I decide to explore Praia Galheta.

This is where the gays go, the locals tell me.

The gays will not mind a topless girl, so I follow the map to a sandy trail that winds down through shrub, cacti, and rock. My first glimpse of the beach is framed through an opening in the brush and it’s a woman alone wearing only black bikini bottoms.

I’ve found my spot.

As it turns out, my spot is not just a gay beach: it’s a nude beach.

Everyone is so shamelessly naked that I immediately do two things I’ve never done before: go topless swimming in public and stroll down the beach afterward to buy a beer.

Going topless in public was something Alberto had often asked me to do.

I shrugged him off—sorry, I’m not that girl—every time.

Somewhere between the beer shack and my beach chair, I realize I feel more confident half-naked on this beach than I ever have in a bikini.

Today’s revelation is bittersweet, but two summers from now, I’ll barely recognize the girl who hiked into this beach. Two summers from now, my only tan lines will be below the belt.

* * *

If Hawaii and Mexico had a three-way with the Hollywood Hills, the Río neighborhood of Santa Teresa would be their lovechild. I follow my guidebook’s advice to take a bonde ride and then wander the area, shooting graffiti walls and architectural details. At sunset, I greet my cousin Brent and his gorgeous girlfriend with hugs at an outdoor restaurant on Ipanema Beach.

All around us, samba street bands are performing.

Teenagers volley soccer balls on the sand.

Local girls teeter in heels, holding their boyfriends’ arms for balance.

Flashes of heat lightning burnish the sky.

Over fresh fish and rice, I share my adventures of the past week and we plot our itinerary for New Year’s. We race each other down to the sea and splash into the dark water, holding our shoes above our heads. Soaking wet and giddy, we walk up the beach singing bits of the Jobim song inspired by this same stretch of sand.

* * *

I spend the day with my cousins on Ipanema Beach, where the local color lives up to its reputation as the most beautiful in the world. Despite the afternoon thunder, we remain sprawled on our towels until the first drops begin falling. We’re drenched by the time we find cover in a hotel bar across the street, where we encounter two Americans from L.A.

The guy has stopped in Río for twenty-four hours on his way to Florianópolis, and he’s friendly with the same American sushi-bar owner I met. The girl spends the majority of our only round of drinks name-dropping and explaining how important it is to mingle with the right people down here, the people who own everything in Brazil.

She lives in West Hollywood, down the street from my old bungalow, and she makes me glad I live in New York now, away from people who talk about how amazing it is to meet celebrities in elevators on their way to record-label parties.

* * *

Brent and Quiana never flinch when I mention Alberto so over dinner at the Fasano Hotel, we reminisce about the Halloween party when I convinced Alberto to dress as a bow-tied professor to match my naughty schoolgirl costume. We have a laugh about Alberto’s fortieth birthday weekend at Greg’s in Connecticut and the framed picture of him as a drum-playing infant that everyone signed.

For dessert, I order a ten-year tawny for me and a Chivas neat for the empty seat.

When it comes, Quiana picks up the scotch and takes a noseful.

This must have been what he tasted like?

Only on vacation, I say. Or weekends.

I do not pick up the glass and sniff it.

I know what will happen if I do.

Instead, I signal for the bill and we move into Baretto Londra, where the three of us dance to mash-ups of AC/DC and Lady Gaga until 4am.

* * *

As the last sliver of Ipanema sun disappears, the beach explodes in applause. The entire city seems to be on its feet, applauding God for a sunset well done. The sight and sound of the standing ovation makes my body tingle and my eyes water.

I turn to the hotel owner who brought us here today, and ask if this is a usual occurrence—the clapping?

Sim, sim, he nods, Brazilians on the beach do this every night. It’s a recognizement of the beautiful day and a way to make praise for it.

* * *

Today is the last day of 2009 and I need to make decisions about the upcoming year.

I’ve done what the CFO requested: I’ve thought about benchmarks. I’ve also run a few financial scenarios and consulted a friend who left corporate years ago to start his own production company.

The facts are these: I can’t promise my PR firm that I can turn over a new leaf and they can’t promise that I’ll make it through the annual review process or be permitted to go to Cuba for the one-year anniversary of Alberto’s death. So we’ll do this like civilized human beings. I will thank them for the opportunity to come back to work and explain that I can’t place a timeframe on this kind of grief. I will tell them that it doesn’t seem fair to make promises I’m not sure I can keep. They will thank me for trying and for being honest about my capabilities—and

limitations.

After Cuba, my life will become a freelance hustle. Gone will be the disposable income and 401k. The luxury of sending out laundry, ordering in for dinner, taking car service to Jersey. No more weekly housekeeper, massages, or bottle service. All of these are first-world blessings—and I’ve lived without them before.

Today I’m choosing the riskier version of my life, but I’ll be living—and mourning—on my own terms.

I begin drafting the resignation letter.

* * *

In the Brazilian custom for New Year’s Eve, I am wearing white and racing into the sea with thousands of strangers at midnight. I jump over five waves and get knocked down by the sixth. I stand up, laughing, and turn back toward the ocean, ready for my seventh wave: the good luck wave, according to local lore.

It does not knock me over.

I climb out of the sea and hug our hostess, a young Brazilian who owns the hotel where my cousins are staying and who brought us to her friend’s VIP party tonight.

You have good luck for 2010, she says, I can feel it. Your seven waves are like being—how you say it—baptized into a new year.

* * *

Like kids in a sandbox, an entire country is dancing, jumping, shouting together on Copacabana beach. All shoes are off, cuffs rolled, dresses soaked. Above us, fireworks explode like stars tumbling out of the sky, a million at a time.

After the finale, we race back to our open-air cabana for capirinha refills, and to the disco downstairs, where a live samba band is performing. Tonight I discover that samba dancing is harder than it looks: the guttural drums are as foreign to me as they are innate to Brazilians.

I can learn you samba, says our hostess, when she sees me trying to imitate the moves. Watch, see. It’s one-two, one-two-three.

All I can see is her bouncing skirt. I have no idea what her feet are doing underneath.

I nod and try to make my skirt flounce at the same tempo as hers, but we are wearing different skirts from different continents that move to different drums. Then again, we’re both wearing white and sweating and drinking and dancing in a basement discotheque. Which pretty much cuts out the cultural clutter.

* * *

I’m watching the first sunrise of 2010 on the beach with my cousins, eight new friends, and fifty thousand strangers.

Amid the champagne-soaked jubilation, I skip down to the shore and swim past the shore break. My body floats in the watery space between neon sunrise and beach party, and my mind between states of gratitude and disbelief. This trip was designed to distract me through my first New Year’s Eve as a widow, and yet it served up the most breathlessly beautiful Feliz Año Nuevo of my life.

If Alberto were still alive, I wouldn’t be here.

Yet my happiness is still happening without him.

I can’t stop the grief or the joy, so I’m splitting the difference between them. And soaking up the moment, like he would do with a bit of bread and the sauce left over from a really good meal.

* * *

We are one of a thousand cars inching up a narrow hill on our way to see the famed Christ the Redeemer statue. After forty minutes and as many feet, the hotel owners who were kind enough to drive me and my cousins suggest that we walk the rest of the way.

This will be faster, they explain.

We thank them, hop out, and head uphill. Ten minutes into our walk, the scene devolves into chaos: pedestrians weave between moving cars, the two-lane road shrinks inexplicably to one, cars are haphazardly parked everywhere. Then we see a line of people that winds uphill for at least a mile.

Whoa, Brent says. It wasn’t half this crowded when I was here for Carnival. And the ticket line was at the top of the hill. Maybe this line is for the shuttle?

This is not America, where signage and park officials actually exist at national landmarks.

I ask the people in front of us what this line is for?

Cristo, they answer.

Tickets? Or autobus?

No sé, they shrug.

Brent is as even keel as they come, but even he’s shifting his weight and checking his watch. He and Qui are flying to Buenos Aires tonight, so the last thing he wants to do on his final day in Brazil is spend four hours in line for a statue he’s already seen.

We continue queuing until a side-view mirror on a descending autobus catches the purse strap of a nearby girl and drags her downhill.

Eff this, I say, resolving to find someone who can tell us how this place works. I notice a Chinese guy in his twenties wearing a Hollister T-shirt and a pair of Persols. He’s walking downhill when I approach him.

Vôce ingles?

Yes, he answers with an American accent.

Awesome! Do you know if this is the ticket line or the shuttle line?

There’s another line up there to buy tickets, he says. It’s shorter than this one. This is the one to get on the shuttle.

So do all these people have tickets already?

Probably not, he says, but they’ll have to stand in it again when they figure it out.

Bless you, I say, and signal to my cousins to follow me.

We hike up to the shorter line, which is essentially a series of bodies winding around cars in a parking lot with no marked spaces. I find a guy selling beers out of a cooler in his trunk, buy a few for us and join Brent and Qui in line.

This line is bearable, especially with a cold Skol in hand, but the lack of posted information nags me. Is there a VIP ticket option that allows you to bypass the second line? Should Qui and I get back in the ridiculous line while Brent buys the tickets?

I hear an American accent and leave my cousins to follow it. When I lose the voice in the crowd, I find myself next to a man with turquoise eyes, a black mullet, and a green futbol jersey.

Que locura, I say. What madness!

He laughs and asks in Spanish where I’m from?

Nova York. And you?

Sao Paulo.

He asks if I have a ticket yet.

My cousins are in line, I say.

When you have your tickets, you can get in this line with my girlfriend and me. She’s right there, he says and points.

The girlfriend waves. She is maybe tenth from the front of the shuttle line.

Seriously?

Yes, yes, he smiles.

Do you need us to buy you tickets, I ask.

No, no, we have, he says, holding up his ticket.

I ask his name, thank him, shake his hand, and dash back to the ticket line. When I approach my cousins, I can hear them talking about Alberto: if he were here, Brent says, he would be asking where is the fucking VIP line already?

I interrupt and tell them I have apparently found the VIP line. I point out my new friend Renal, who’s holding our place at the front of the line.

You’re amazing, Brent laughs.

We’re getting some extra help today, I say.

Tickets in hand, we find Renal, who ushers us into an air-conditioned shuttle that ascends through clouds and around hairpin turns, lurching to a stop at the Roman staircase leading to the Cristo statue.

Jesus, as it turns out, does not know how to take a bad picture. I shoot a dozen of him with a sun halo and squeeze my way through the sweaty tourists toward the balcony jutting thousands of feet above Río. When I land my real estate, I take out the bag of flowers from my hotel garden and Alberto’s ashes. I cross myself, take a handful of each, and release.

It spreads out like a fan through which I can see the entire city, the ocean, and the huge rock formations that look like pebbles from this elevation. The view makes me sob in happy-sadness: if Alberto were here, he’d be so effing awestruck that he’d forget his fear of heights. He’d still be mad that I dragged him to the top, but I’d remind him that he got me over my fear of going topless, so I’m just returning the tough love.

The conversation in my mind leaves me smiling throughout this ritual—first time ever—until I’m shoved from behind by loud German women. Turning around, I meet the eyes of Renal over the heads of the Germans.

I mouth the words muchas gracias, and touch my fist to my heart in gratitude. He nods and smiles before disappearing into the crowd.

I continue spreading Alberto’s ashes and flowers until he’s gone.

There’s one flower left, which I kiss and release two thousand feet above the City of God.