Ring on the Right Hand

* * *

For the first morning in nearly four months, I’m getting ready for work.

Vanessa’s presence fills the silence, eases the void, and keeps my tears at bay. She stands at the front door and sees me off, the way I did with Alberto, waving until the elevator doors close.

When the fashion department rushes me with hugs and smiles, I realize how much I’ve missed them. But when I arrive at my desk—with its postcards and framed pictures of Alberto and me—the hyperventilation starts.

Last time I sat here, Alberto was still alive.

I clear my throat, trying to push the grief away, and notice my office voicemail blinking.

Messages.

Something people check after vacations—or bereavement leave.

This is where I start, and by mid-afternoon, muscle memory kicks in. I email a few favorite journalists—long time, no stalk!—do a few tedious conference calls, and meet the newest hire: a digital strategist named Sharon who’s rocking a fierce pixie cut and a vintage dress.

But when the receptionist brings me pink, yellow, and green roses in a bark-wrapped vase, I am stunned into silence.

Who sent you flowers, Tré? someone says, a few desks away.

Not the person who used to, I say, before my teeth can stop it.

Alberto was a man who knew how to send flowers: often and well arranged.

Orchids or gardenias or Ecuadorian roses would arrive at my office after I’d spent the weekend at his office, editing his agency’s latest presentation. After I’d nursed him back to health following ear surgery—or a silly cold. A few days before our anniversary. The week of my birthday. On the November date of my brother’s accident.

And always.

Always when I started a new job.

Though the flowers are from my parents, they are exactly what my desk was lacking today.

* * *

A cocktail convention in the French Quarter ain’t a bad way to spend your first weekend back on the job.

But as I pack for the trip, I keep flashing back to Alberto sitting on the sofa, watching me get ready for business trips: You’ve been packing for two hours! You’re taking the big suitcase for a weekend trip? You’re bringing those shoes—with that dress?

Still deciding whether I miss his teasing more than I appreciate my privacy.

* * *

During a working dinner in the Quarter tonight, I keep thinking I should duck outside and check in with Alberto. A thirty-second call or text went a long way with him when I entertained clients or journalists.

Miss you, my text would say. Sorry my dinner is running so late. See you around eleven!

His reply?

I’ll be here . . . at the intersection of Loneliness and Abandonment.

Nobody is waiting at any intersection for a check-in text from me tonight, so I try to focus on memories that have nothing to do with Alberto.

Nine years ago, I spent ten days in New Orleans with my friend Hoffman. He was the jokester buddy of my Malibu boyfriend, and one of the few people I didn’t lose in the divorce. A year after my break-up with his friend, Hoffman was in law school at Tulane and I was at Berkeley. It was the year 2000, when my birthday happened to fall on Fat Tuesday.

You should fly in, he said. Stay Mardi Gras week. We’ll kill it for your birthday, brah.

I flew to New Orleans, met the three other girls who were staying the week, and promptly staked my claim to a sitting-room sofa.

Yeah, didn’t sleep there much.

Host-With-the-Most Hoffman had actually arranged a personal tour guide for me: a smooth, green-eyed local with a legendary . . . pedigree. When the local wasn’t showing me the nuances of NOLA’s underbelly, Hoffman was introducing me to the flourless chocolate cake at Commander’s Palace, a tree named Grandfather at Audubon Park, and the best patch of neutral ground to watch the Zulu parade.

So, yeah, killed it for my birthday.

Over beers in California several years later, he winkingly confessed to sleeping with all three of those girls that week. And his supposedly platonic female roommate.

I may have called him a man-whore and high-fived him.

By 2004, he’d settled into a career as an L.A. attorney and would appear at my West Hollywood door on his Friday-night commute. Over Greek food, we’d swap sport-dating adventures or get buzzed and go to MOCA. Jumbo’s Clown Room, read-alongs of Richard Feynman, and Saturday-night benders were usually involved. Hoffman kept an extra suit in his car, which came in handy if Monday morning happened to find him on my living room couch.

I gave Hoffman his first head shave—it’s not coming back, dude, gotta let go of the dream—and he gave me my first proper shoe shine. I may have scrubbed his vomit from my bathroom walls once and he might have paid my rent one Christmas. We slept in the same room dozens of times but our first kiss was one week before I met Alberto. There would be no second kiss.

Two years from now, I will receive news that Hoffman died in L.A. at forty-one.

Heart attack.

He was found in an armchair, slumped over a book.

Among a thousand other things, I will wonder if the book was written by Richard Feynman.

* * *

Apparently New Orleans has the same insomniac effect now as it did nearly a decade ago: I was up until 7am talking to a man I met last night. We shared a few drinks and the same hotel room, but not so much as a kiss. Did this morning’s walk of fame with my head held high.

* * *

Only a week back in the real world, and the small talk is killing me.

Why is every manicurist and bartender and industry person compelled to notice my rings and ask how long I’ve been married? Did these same unsolicited questions happen when he was alive?

What if I take off my wedding band altogether and shift my engagement ring to the right hand? Is that enough of a social signifier? A sign that something’s askew—and it’s best not to press for details?

Staring at the absurd tan line on my ring finger, I find myself willing it to both fade and never fade.

* * *

Today’s mail serves up a few catalogs addressed to Alberto and a letter from my biological grandmother. She and my father, the son she gave up for adoption in 1951, located each other nine years ago and have been in distant touch ever since.

Her letter addresses a reoccurring theme—how do she and my father fit into each other’s adult lives?—and I find myself in a familiar but awkward spot. She writes to me because I’m the granddaughter and one generation separates us from guilt or abandonment issues. She writes to me because she knows I do not judge her.

Cannot judge her.

Unless I’m willing to judge myself for making the same decision when I was eighteen years old and pregnant.

It was the last semester of my senior year and six weeks after I’d broken up with Griffin, a half-Filipino fellow I’d dated for three torrid, drug-fueled months. I’d quit the fellow shortly after quitting the drugs, and sobriety had rewarded me with a California high-school diploma, driver’s license—and a positive pregnancy test.

After breaking the news no parent wants to hear, I escaped on a previously booked spiritual retreat in the mountains. At six weeks pregnant, there was no baby bump and my morning sickness was likely seen as an eating disorder.

Two nights into the retreat, I was attending an indoor meditation session in a large cabin on the mountain.

Eyes closed, mind cleared, moon full.

I was repeating this mantra until a voice startled me. Not one of those still, small voices you hear on the way to the airport, asking if you turned off the flat iron: this is a loud, wake-the-dead kind of voice. And it’s saying things no one but me knows.

My eyes fly open, looking for the source that’s just outed me.

The room is silent and oblivious.

I’m the only idiot with her eyes open.

I shake it off, take a breath, and close my eyes again.

The voice—neither male nor female—speaks and once again, I am gaping at a room full of people who are oblivious to me. I start wondering if hallucinations are a side effect of pregnancy and close one eye, then the other.

I cannot stop the tears when The Voice happens a third time, so I rush outside, away from the words Therresa, you need to give this child up for adoption. I’m halfway up the mountain—I’ll outrun The Voice!—before my throat goes so dry that I have to stop, heave, and throw up.

Dinner evacuated, I hike blindly up the mountain with bare feet until the full force of what just happened in the meditation room hits me.

I collapse on rocks and pine needles, sobbing like a girl.

God?

Is telling me?

To give this kid up for adoption?

As I’m saying these words aloud, it occurs to my eighteen-year-old brain that if God is telling me to do this, then I will not have to do it alone.

I came down from the mountain and told my parents I was giving my child up for adoption. Dad was adopted, so no judgment there. My mother responded by suggesting a summer trip to Idaho—where my parents lived while my dad attended University of Idaho at Moscow—to think things through.

Sure, I said. But my mind’s made up.

Good for you, she said. Oh, I’m buying your brother a ticket too.

I can take care of myself, I said.

I know you can, she replied, but Phil’s going with you.

I’d heard Griffin was seeing other people and since he hadn’t bothered to show up for any of my doctor’s appointments, I didn’t bother sending him the adoption memo before heading north.

The eight-week trip to Idaho with Phil was arranged and summer jobs were landed: me as a florist’s assistant and him as an apprentice plumber. We met for lunch most weekdays and at the Moscow mall on weekends. Every Saturday, he’d do his laundry at the farmhouse where I rented an attic room from a college professor’s family.

It was in this small town of Moscow that I had lunch with the same pastor whom I would ask, sixteen years later, to perform Alberto’s funeral and who would refer me to Pastor Weinbaum with the striped socks and shaved head. During this lunch, the Idaho pastor gave me letters and photos from couples who wanted to adopt. After corresponding with a few potential adoptive parents, I spent a long weekend in Boise with the front-runners. Jack and Lisa aced my teenage litmus test: thirty-ish homeowners with masters degrees; Christian but not culty; political views that didn’t make me cringe. After forty-eight hours, I was convinced Jack and Lisa were The Parents.

I decided to stay in Idaho for the remainder of my pregnancy, but my parents weren’t letting Phil skip out on his senior year of high school. In late August of 1993, I accompanied him to a small airport in Washington, from which he would fly to Spokane and then to California. We hugged on the runway and I gave him an envelope containing a four-page letter and one of those cheesy Blue Mountain poems entitled “Why You’re the Best Brother.”

So Phil went back to California and I immersed myself in the Pacific Northwest. I joined the professor’s family of four on outings that involved pressing apples into cider at a Washington orchard. Going to a pumpkin patch in the middle of Montana. Attending Christmas concerts of Handel’s “Messiah” and performances of Swan Lake at the University of Idaho. Going to Lamaze class on Tuesday nights and writing anyone in California who would write back.

Anyone except Griffin, whom I didn’t trust with my whereabouts. His temperament was equal parts lazy and crazy: he’d blow off simple traffic hearings—knowing the penalty was jail time—but he’d also spent months building a lawsuit against his big-box employer . . . and won. Common hassles were beneath him, but big, impossible battles? Those were the sort of quixotic pursuits he went in for.

My California friends had laughed at my warning to keep my location a secret—you’ve seen Sleeping with the Enemy too many times—yet I never quite shook the sense Griffin might appear on the farmhouse porch or outside the florist’s shop.

But my due date came and went with no sign of him—or labor.

My brother and parents also came and went, flying up to spend Christmas with a very swollen version of me.

The day after they left, I worked until noon before heading to my weekly doctor appointment and learning that my ob-gyn was going on a New Year’s ski trip.

Dr. Chen will take great care of you, he assured me.

Dr. Chen? I said. Who the hell is Dr. Chen? You are my doctor and you are delivering this baby. I am not meeting some new guy with my legs in stirrups.

He sighed, looked at his watch, and agreed to induce me.

Today.

Now.

He proceeded to strip my membranes—with something that looked not unlike a knitting needle—then told me to drink some caffeine to boost the baby’s heart rate, pack a bag, and meet him at the hospital at 2pm.

I stopped to tell the florist I’d be back next week—having a baby today, people!—and got a soda with lunch before walking the mile home to pack a bag.

Three hours and seventeen minutes after arriving at the hospital—without so much as a Tylenol despite grand plans for an epidural—Laurie Therese was born.

A day later, her parents arrived and I held her for the last time before going to the Moscow courthouse and signing away my biological rights before a judge.

Six weeks—and thirty sessions with a personal trainer later—I was back in California, rediscovering my pre-pregnancy wardrobe and life. While Laurie spent her first year doing newborn things, I returned to my parents’ house, enrolled in junior college, and took a museum job.

And that four-page letter I gave Phil on the airplane runway?

The day he died, I will find it pinned to his wall, behind the cheesy Blue Mountain poem.

I will re-read it a dozen times while trying to write his eulogy and plan the service.

It’s what I will read aloud—in lieu of a eulogy—at his funeral.

In the years to come, I will flinch at its easy clichés and prescriptive tone, but even more, at the inescapable sense of a sister saying good-bye—twice.

August 30, 1993

Dear Phillip,

I can’t believe you’re leaving! These two months have flown by, haven’t they? It’s been so fun being stranded up here together! I think we’ve had more meals together this summer than we’ve had in two years!

Man, Idaho will not be the same without you to nod at and say “Idaho thing” simultaneously. Who else will shake their head with me at the sight of a dessert pizza (so weird) or people square dancing in the middle of the street? Or when someone offers me kohlrabi (i.e. vegetable that tastes like dirt)? Who else will laugh at a “Clucker’s Club” sign or at someone bumpin’ Vanilla Ice? Who else will ask my not-so-cheerful boss if his sister can please leave for lunch?

I will miss you, little brother, but have to admit how very proud I am of you. You’ve proved yourself responsible, respectful, and dedicated . . .

those are serious accomplishments for only eight weeks! Be confident there’s nothing you can’t achieve once you decide to try your best.

I am so blessed that you decided to resume high school. Since you’ll be done so soon, maybe we can go to college together . . .

wouldn’t that be killer?

On a more serious note, we both know our family isn’t what it was when we were younger. But that doesn’t mean it never will be—it just means a little cooperation and a lot of prayer is needed. Please don’t feel helpless if Dad disappoints you or frustrated if Mom gets on your nerves. But please think when you have the urge to yell or slam a door. Are you hurting their feelings or showing them

how much you love them?

You can make such a difference on our family. It’s up to you whether that impact is negative or positive. Please don’t take that wrong: I’m saying how vital you are to this family and thus recognizing how much you influence it. Thinking before you speak or act will be hard at home—believe me, I know!—but you’ve grown up so much lately

that I know you are capable.

I’ll be praying and rooting for you, Phil, as will many others. And if a situation or decision arises that you feel confused about, don’t hesitate to call me or ask for prayer. I’m proof that it can work miracles!

Not a day will go by that I won’t think about how much I miss you.

But I am comforted just knowing that you are pursuing a goal

of your own . . . and that I’ll see you at Christmas!

(I’ll be big as a house, no doubt!!)

I LOVE YOU!!

Your Sister,

Therresa

Griffin was among the several hundred people who heard my letter-as-eulogy. Undaunted by the circle of friends around me, he had approached during the after-thing at my parents’ house.

Can I have a word, he asked. Outside?

I nodded and stepped onto the porch.

In a quiet voice, he told me how sorry he was about Phil.

I think I finally understand the whole Idaho thing, he said. And I’ll sign whatever you want me to. I just want to make things right.

For the last eleven months, he’d done everything he could to make things wrong.

He had—as I feared—made a trip to Idaho after all. He’d shown up in a Boise courthouse the same day the adoption was to be finalized and petitioned for full custody of Laurie. I learned of this development when he called me from a pay phone afterward.

I’m gonna get her, he snarled. And you’ll have to pay me child support.

I laughed out loud.

Yeah, you and what army?

I lost no sleep over Griffin’s posturing.

Because—let’s review—I’d heard the voice of God on a freaking mountain.

The Voice said adoption.

I’d kept my end of the deal.

God had my back.

The Idaho lawyer who took my case pro bono put in a hundred more hours than he planned. The adoptive parents did a lot of hand-wringing. Phil had taken matters into his own fists and given Griffin a black eye.

And now, out of respect to Phil, Griffin is holding out the white flag.

I don’t make him wave it twice.

I march upstairs in my funeral dress and find the form my lawyer had faxed over months ago just in case. I stand over Griffin while he signs it in my parents’ living room. By the time full parental rights are awarded to Jack and Lisa a year later, Griffin will be back in jail: a fix-it-ticket-turned-bench-warrant, no doubt.

I will graduate Berkeley a few years later on Mother’s Day and Laurie will move to North Carolina with her three adoptive sisters and all-American parents. According to their most recent letter, she’s the fifteen-year-old star of her cross-country team who loves to entertain and wants to go into criminal justice or culinary arts when she grows up.

* * *

It’s the four-month-iversary of Alberto’s death and my first official day “leading” the PR strategy for one of the world’s biggest vodka brands.

Nine conference calls scheduled this week?

Nearly two hundred incoming emails in four hours?

Can I even do this?

I contemplate quitting all morning.

When I return from lunch—a loose word for three cigarettes, one tweet, and half a banana—I’m greeted by the office doorman, who always has a kind word or compliment for me.

Today I’m in no mood for banter, so I smile and pass through the lobby quickly.

As I wait for the elevator, I hear him say he can’t quite put his finger on it.

On what, I ask, reflexively.

What’s different about you. You’re still smiling like the sun, but it’s a—heavy smile.

The elevator arrives.

I can’t get in fast enough.

He reaches out his arm to stop the closing door and waits for me to say something, explain something.

There’s a reason, I say, but if we keep talking like this, Warren, I’m gonna cry. And I cannot be crying on the twelfth floor.

I press the DOOR CLOSE button and this time he doesn’t stop it, but as the elevator ascends, I hear the faint refrain of his voice.

I just can’t put my finger on it.

Who am I fooling, I think. I can put on lipstick, high heels, and a brave face every day—but for what?

Even doormen see right through me.

* * *

I don’t know how to do this.

How to have dinner with the man I met in New Orleans, who happens to live in Brooklyn.

Feels like I’m cheating.

And incapable of graceful conversation.

The man is asking if I cook, but this question doesn’t come with a simple-dimple answer.

Other than warming a can of tomato-and-rice soup or milk for a latté, no, I haven’t made a thing in our kitchen in four months. Every stupid pan reminds me of meals for two: Meyer lemon pasta, swordfish, tacos with “Tré’s mystery meat,” Boston lettuce salads with blue cheese, eggplant parm from Da Silvano’s cookbook. I’ve been to the market exactly twice since Alberto died.

So to answer your question: Yes, I used to cook. I don’t anymore.

Any more awesome questions?

Turns out, he has lots of awesome questions.

I can’t stand any more, so I ask two of my own: Can you drop me off in Chelsea? Or should I just take a cab home?

I’ll drive you, he says.

I thank him for dinner—and for being a gentleman.

We both know we won’t keep in touch: the Alberto-shaped space between us is too massive.

* * *

I’m the white elephant in the room.

In the sanctuary, specifically.

Someday I’ll feel comfortable enough to stay after the sermon with other churchgoers, but at this part in the movie, I haven’t recovered enough of my small-talk skills to have coffee in the basement with Pastor Weinbaum’s congregation.

With any congregation, for that matter.

I duck out the church’s side door, wishing widowhood came with an invisible force field that gently—and wordlessly—repelled others on demand.

* * *

I can’t be the only idiot in NYC who’s noticed the sound the subway makes as it takes off?

How similar it is to the first few notes of “There’s a Place for Us?”

Before meeting Alberto, I didn’t know this song—or anything else by Barbra Streisand.

He’d found this impossible to believe.

Are you saying you don’t know the People Who Need People song?

Sorry, I said. When you sing her songs, I’ve got nothing: not the next note, not the next word.

Shee-ott, he said. You gotta get educated, girl.

My education began that night, when he launched an iTunes session of Babs 101, and continued through our marriage.

Hearing the sound of Streisand in the subway today and not being able to text him makes me want to climb out of the metro, out of the moment, out of the memory.

* * *

My office has kindly granted me time off for Alberto’s birthday and the days surrounding our wedding anniversary. I want to get out of the City, as far from familiarity as possible, but I need co-pilots.

I text Maggie, who accompanied me to Sway a few months ago, and ask if she’s free for my anniversary weekend?

Hell yes, she replies. Let’s make like a hurricane and blow.

Since Tony Papa’s birthday is two days before Alberto’s, he suggested we meet up for a long weekend.

Just pick a city, he said, and I’ll meet you there.

I start considering destinations.

Alberto never got to Vegas—still can’t wrap my head around that—but I’ve been a hundred times and so has Tony.

Puerto Vallarta?

Too much traveling for a three-day weekend.

Puerto Rico?

I’ve heard that’s where Alberto met his first wife, so um, no.

Grand Canyon?

Too hostile in August.

Aspen?

It’s nothing without snow.

I’ve heard North Carolina’s beaches are lovely, but my biological daughter vacations there and should we ever meet, I’d rather not be swimming in a bucket of grief.

I give up on the birthday destination for now, and head out to meet Nikki and Fico for Wednesday night dinner at their place. En route, Nikki texts and ask if we can meet at Ditch Plains instead? It’s the Manhattan outpost of a restaurant in Montauk where Alberto and I dined on our first anniversary, but for once, I actually keep this information to myself.

After a perfect summer meal of oysters, rosé, and fish tacos, we walk through the West Village. Fico points out his favorite townhouses and Nikki describes interiors of landmarked brownstones they once visited on a historical tour. They share stories about their college romance at Hobart and long-distance courtship when Fico worked for an ad agency in Chicago. We part with leisurely hugs on Hudson, and I resist Fico’s offer to hail a cab for me.

I’m gonna walk, I say. It’s a lovely night.

I head north and pass a wine store Alberto and I frequented. The brunch place with good omelets. The park on Bleecker where we always seemed to run into friends with kids.

Yeah.

Enough with the memory lane already.

I see a cab thirty feet ahead and shout for it. The cabbie doesn’t hear me, but the exiting passenger does.

He holds the cab, but disappears before I can properly thank him.

Bless you, I shout as I slide into the backseat, thanking God for the benevolence of strangers.

* * *

Certain objects in our kitchen comfort me.

The sofrito sauce in the fridge is like a familiar stranger whose name I’m surprised I remember but I’m always glad to see.

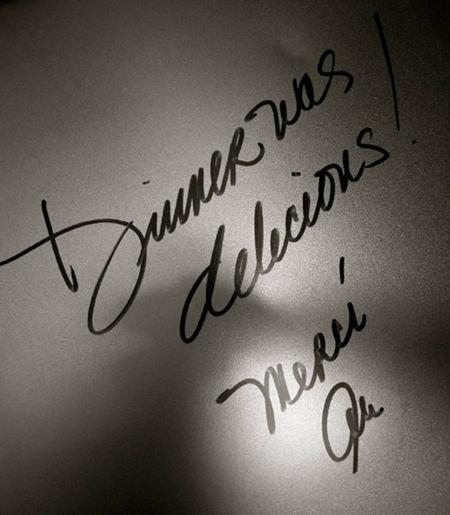

Alberto’s cursive handwriting on the silver dry-erase board still makes me grin like a schoolgirl.

But his row of cereal boxes atop the fridge?

Not so much.

But why? Because he’ll never finish them?

Yes.

Actually.

That’s exactly it.

So why keep them around? Do I not encounter—at every turn—furniture, art, bathrobes, and razors that remind me of him? And these objects, for the most part, don’t inspire the same anxiety as the cereal?

I take a picture of the cereal boxes and carry them to the trash chute.

* * *

Over a bottle of wine at my sister-in-law’s in Jersey, we have our first unfiltered conversation about Alberto since It Happened.

So, Barby says, did he ever tell you about the time he got arrested on New Year’s Eve in Miami?

Um, no, I laugh.

Really? So Albert calls me from jail—

Wait—how old was he?

Well, I was going to college in Tampa and my father was still alive, so Albert would have been—well, he’s three years older—twenty-one or twenty-two?

Before he moved to New York, I say. Got it.

So he gets pulled over on his motorcycle—one of those, what do you call ’em—a rice something?

A rice rocket?

Exactly. So he’s pulled over because apparently his helmet isn’t regulation. But when the cop runs his license, there’s a warrant for his arrest—

For what?

Unpaid parking tickets—which Albert claimed that my father had supposedly paid. So yeah, they take Albert to jail and he called me to get our father to bail him out.

So you call your father, I interrupt.

Who basically had no money at that point. And he played dumb about the whole parking-ticket thing.

And your mother?

Right. My mother.

What did she say?

She was in the Dominican Republic or Costa Rica or wherever she went for the holidays that year. No cell phones back then.

Right. Of course.

Which leaves me to pick up money—not enough, mind you, because like I said, my father was broke—and drive around the ghetto looking for the Miami jail.

So his little sister bailed him out of jail?

Tré. It was like $5,000. Doris—no, Doris’s mother—bailed him out. She used her house for collateral.

No shit?

Well, you know Doris. She and Albert are like you and—who’s the guy you’ve known since you were twelve? Came to your wedding? Came out for Albert’s funeral?

Tony Papa.

Exactly. So Doris and her mother put up collateral and I pick him up. Then, as we’re walking to my car, I ask him where his jacket is? Don’t ask how I knew he had a jacket—must’ve been cold in Miami that day—but he tells me that a drunk in the holding cell took it from him.

What?

The Alberto I knew would never let some inebriated asshole steal his jacket. Or let parking tickets turn into a warrant.

But this was Alberto before I met him.

This was nineteen sloppy years ago.

Still.

The stolen jacket.

It brings me to tears.

At this moment, I finally understand why my mom still chokes up about my brother being bullied in grammar school: she wishes she could-have-would-have stopped it.

But it wasn’t about stopping a bully.

It for her—really—was about stopping Phil’s car crash.

And it for me ain’t about stopping a drunk from taking Alberto’s jacket.

It’s about stopping his heart attack.

* * *

I can admit it: I sleep with a stuffed monkey every night.

When I make the bed each morning, I set him atop the duvet and position his limbs and head at a playful angle. When I leave the apartment, I wave good-bye. I pack him into my suitcase on trips—even if it means checking oversized luggage.

The stuffed monkey was a gift from Barby three mornings after It Happened.

She and Hilda had come to the apartment and when we settled in the living room, Barby mentioned the christening of her daughter, Teresa.

Remember how you and Albert came back to the house after the reception?

Yes.

Well, Albert got rather attached to Teresa’s stuffed monkey that day.

I laugh.

He actually threatened to leave with it. But I told him he wasn’t allowed to steal his own goddaughter’s toys.

But, Hilda interrupts, Barby went to the same store—Macy’s, I think—and bought the exact same monkey for Albert.

Really?

I was gonna send it to Albert’s office, Barby explains, along with a note supposedly written by Teresa:

Dear Uncle Albert,

Get your own damn monkey!

Love,

Your Favorite Goddaughter

That’s adorable, I say.

Barby shoots me a silencing look.

I never should have put it off, she shakes her head. It sat in a shopping bag last week and—

But where’s the monkey now, I interrupt.

She has it here! Hilda shouts, her ice-blue eyes sparkling.

I perk up as Barby returns from the foyer with a latté-colored monkey.

I’m on my feet as soon as I see it.

Its face.

Looks.

Like.

Alberto’s.

Same amused smile. Same dimples that only emerge when he’s either really happy or really not.

And that silly, stuffed monkey?

It’s the only reason I’ve been able to sleep for the last four months.

* * *

Nothing like a Times Square cabaret to drive you to tears.

Luckily, it’s too dark for anyone to notice, because explaining to Alberto’s employees and business partner why I’m crying through a song about an air conditioner would be awkward. The air-conditioner song is being performed by Kerri, the PR director, and I’m so floored by her retro voice and shameless stage presence that I can’t help wishing Alberto was seeing this show.

But I have no doubt that he would show his approval by interfering with her performance. At the office, he’d dump Kerri’s yogurt onto her keyboard. Lick her water glass. Send her handwritten hate mail just for fun. One of his other female employees told me she’d once gone into the office bathroom and on the mirror, someone with handwriting just like Alberto’s had written: For a good time, call 646-248-4802.

This was her actual phone number.

And she got a call from some guy in the office.

* * *

I’ve seen better nights.

This one finds me opening drawers in pursuit of a pill—any pill—that will make me feel better.

An Oxycontin lifted from Alberto’s vitamin bottle looks promising. He’s not here to explain this pill—from his ear surgery? knee surgery?—and I’ve never tried oxy, so I take only half the pill.

I swallow it without water, start closing the drawer, and notice my silver Rolex.

The one Alberto put on my wrist in D.C., as a token of his intention.

I don’t recall wearing it since he died . . . has it been in a drawer all this time?

The oyster perpetual date on the watch reads MAR 15.

It stopped . . . the same day he died?

What time?

6:47am.

Was. This. The. Exact. Moment?

Last time I saw him alive was 6:42am.

I remember the degree of lividity he already had at 8:21am.

Actual time of death?

6:47am?

He was dying while I was drifting off to sleep?

As the pill kicks in, I stare at the clock face.

Can’t move it.

Can’t wear it.

The motion-activated battery will start ticking.

Time will start again.