![]()

NO CITY has quite the magic of Venice. Protected by the lagoon, Venice emerged as a powerful entity in the Dark Ages. By 1000 she controlled the coast of Dalmatia and her destiny as a great colonial and trading empire was set. By the fifteenth century she had gained control of much of northern Italy. A patrician republic, La Serenissima, under an elected Doge, Venice retained her independence until the French invasion of 1797. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance it was her wealth and power that impressed the world, in the seventeenth century her constitution that was admired, not least in England. With the eighteenth century it was the very fabric of Venice that delighted the outsider – as Canaletto and Guardi learnt to their profit – and the fascination that the city would continue to exercise can be experienced in the pictures of Bonington and Turner, in the impassioned writings of Ruskin, and in the equally eloquent responses of three cosmopolitan Americans, Henry James, Whistler and Sargent.

Despite the development that has disfigured so much of the Veneto, the most memorable approaches to Venice remain the old roads, the villa-lined Terraglio from Treviso or the route beside the Brenta through Dolo and Stra. A causeway now crosses the lagoon towards the city that seems to lie on the waterline. The Grand Canal cuts a reversed S course that divides the city in two unequal sections. This is the main thoroughfare of Venice, designed to impress. And it does. The tourist should take the vaporetto (Linea 1) that proceeds down the canal, sitting near the bow so that you can be mesmerized by the kaleidoscopic sequence of churches and palazzi. The canal runs eastwards to curve towards the Rialto, the elegant bridge that marked the original commercial heart of Venice; its course continues south and then to the east and at length commands the celebrated view of Santa Maria della Salute and the Dogana, with the Molo.

The Molo was the scene of many of the ceremonies of the Venetian republic: to the right is the prodigious Gothic ducal palace, to the left Sansovino’s majestic Libreria. The Piazzetta between these is dominated by the rebuilt campanile and by the spectacular lateral view of the many domed Basilica di San Marco. The basilica is the spiritual, indeed the emotional, centre of Venice. The wonderful drama of its façade and domes, and the measured rhythm of the interior, impress immediately; the remarkable mosaics take much longer to digest. The magic of the place is most palpable in the early morning, when those who want to pray can visit the north transept. But return later as a tourist to wonder at such miracles as the Pala d’Oro, the jewel-studded altarfront. The treasury must be the most remarkable in Italy, and the panels by Paolo Veneziano in the museum mark the highpoint of Gothic painting in Venice. The galleries above the nave, alas, are less accessible than in the past; and admirably as these are now displayed, it is a poor commentary on our polluted and polluting world that the great classical bronze horses from Byzantium have had to yield their places on the façade to replicas. That the bronzes, like the inscrutable Tetrarchs of porphyry in the Piazzetta, were spoils from the Fourth Crusade of 1204 makes one feel a little less resentful of the depredations Venice would suffer in her turn.

San Marco: the Tetrarchs.

The Piazza San Marco faces the west front of the basilica. It is flanked by the Procuratie Vecchie, to the south, and the Procuratie Nuove, the last begun about 1585. Tourists now outnumber Venetians under the loggias. Yet of the piazza itself one never tires.

Even when crowds mean that the basilica and the ducal palace are untempting propositions, the piazza is a logical place from which to set out. My choice depends on the time. In the mid-afternoon I would make east for San Zaccaria, hoping to catch the sun on the inexorably beautiful late altarpiece by Giovanni Bellini. I might then go on to San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, the confraternity of the Dalmatians; in the lower hall, in their original positions at the height the artist intended, are Carpaccio’s celebrated canvasses that are among the masterpieces of Venetian narrative taste in the Renaissance. Ruskin at one time considered the Triumph of Saint George the finest picture in the world, while Sir George Sitwell would create a room inspired by the Vision of Saint Augustine; and any observant child will delight in, for example, the detail of the Saint George and the Dragon.

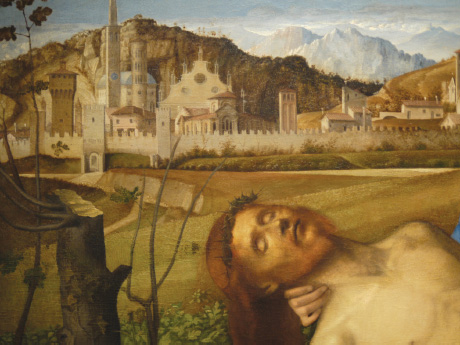

San Zaccaria: Giovanni Bellini, The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (detail).

One of the pleasures of Venice is trying to lose the way. I like to wander. An early start from the piazza might take me in a northerly arc, by way of the campo of Santa Maria Formosa, to Santa Maria dei Miracoli, the most exquisite church of Renaissance Venice, built in 1481–9 to the design of Pietro Lombardo. Further north is the Gesuiti, with a dramatic masterpiece of Titian’s maturity, the Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence. Beyond is the Fondamenta Nuove, where Venetians still outnumber their visitors. There are boats to the cemetery island of San Michele, to Murano and to Torcello, with its matchless Romanesque cathedral. But I might prefer to resist these temptations and to make on, keeping as near to the lagoon as possible and crossing at least five bridges, for the Madonna dell’Orto. This is a majestic late Gothic brick church, memorable not least for its pictures. Cima’s Saint John the Baptist with other Saints is as sharp in detail as any relief by the Lombardo and perfectly controlled in colour, while Tintoretto is found at his most cerebral – in the Presentation of the Virgin – and at his most visionary – in the Last Judgement of the choir.

There are few more charming areas of Venice to linger in. But the more committed sightseer will take one of the bridges over the canal and find his way, passing perhaps the Ghetto Nuovo, to the Canareggio canal. Across this is the most abused of the great churches of the city, San Giobbe. The right wall of the nave is lined with the altar frames of masterpieces by Basaiti, Bellini and Carpaccio, all long since immured – as if in a sanitized hospital ward – in the Accademia.

Accademia: Giovanni Bellini, Donà delle Rose Lamentation (detail).

The Accademia must take pride of place among the museums of Venice. For there, as nowhere else, the miraculous kaleidoscope of Venetian painting from Paolo and Lorenzo Veneziano to Rosalba Carriera and Guardi can be surveyed. Go early and linger for as long as possible in the small rooms with the Bellini Madonnas, his Donà delle Rose Pietà and Giorgione’s Tempesta. But do not neglect the less intimate masterpieces, Bellini’s San Giobbe altarpiece, the haunting late Titian Lamentation, the major works by Veronese and Tintoretto, or Carpaccio’s grandest achievement, the sequence of canvasses of the life of Saint Ursula.

Venice’s civic museum, the Museo Correr, is also remarkable: the Bellinis there can still be seen in natural side light, as the artist would have expected. The Ca’ d’Oro is the most elegant of early fifteenth-century Venetian palaces. Alas, the ruthless recent reorganization of the collection means that one can no longer sense the tact with which Barone Franchetti treated the house. The institutional fate of Ca’ Rezzonico, the greatest of the eighteenth-century palaces, also on the Grand Canal, has been kinder: the collection of Settecento pictures, furniture and sculptures perfectly complements the building.

Accademia: Vittore Carpaccio, Return of the English Ambassadors, from The Legend of Saint Ursula (detail).

Remarkable as the resources of these institutions are, the achievement of the great Venetian artists is best understood by seeing works of art that remain in context. Within a triangle marked by the Frari, San Sebastiano and the Gesuati, opening hours and the whim of sacristans permitting, an astonishing sequence of masterpieces can be experienced.

At the apex is the vast late Gothic Franciscan church of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. The building is well named, its brick apses without rival, the campanile only exceeded in height by that of Saint Mark’s. The sustained richness of the interior is almost impossible to describe. The choir is dominated by Titian’s triumphant Assumption, a work of unparalleled ambition. Later, by 1526, the artist would supply his equally remarkable – and in some ways more influential – altarpiece for the Pesaro family. The two pictures were potent statements of an artistic revolution that owed so much to the painter’s early mentor, Bellini, whose incomparable triptych of 1488 in the sacristy, still in its proper frame, had in turn been revolutionary in its day. Other major Venetian churches are rich in sculpture, but none competes in range perhaps with the Frari, for impressive state monuments to public figures are complemented by Donatello’s spare Saint John the Baptist and Canova’s pyramidal memorial to Titian.

Behind the Frari is the Scuola di San Rocco, grandest of Venetian institutions of the kind. The building was begun in 1515, but in view of its scale it is hardly surprising that work proceeded slowly. The lower hall, vast and tenebrous, is adorned with a series of eight canvasses by Tintoretto, all but two drawn from the New Testament. Tintoretto was also responsible for the ceiling compartments and twelve further scenes from the life of Christ of the upper hall and the ceiling and Passion scenes of the adjacent hostel, culminating in the prodigious Crucifixion. Tintoretto as a portrait painter was truthful and objective; as a religious master he is no less truthful. He has a force that demonstrates that his study of models after Michelangelo had not been vain. But his sense of drama is his own. And his technical abilities were perfectly calibrated for the project.

It is not easy to look at any work of art after brooding with Tintoretto at San Rocco. So it is as well that there is a short walk to Santa Maria del Carmelo, where a supply of coins is necessary to illuminate Cima’s tender Nativity of c.1509 and Lotto’s Saint Nicholas in Glory with its irresistible landscape. If a sacristan is about, ask to see the bronze relief of the Deposition with portraits of members of the Montefeltro family by the Sienese Francesco di Giorgio in the right apse.

From there it is a short way to San Sebastiano, built between 1505 and 1545, where the third giant among Venetian painters of the time worked over a long period from 1555. Paolo Caliari, il Veronese, lacked perhaps the spiritual fervour of Tintoretto, but at San Sebastiano he demonstrates his full range, although the large Last Supper from the refectory was among the pictures removed by the French to Milan and so is now in the Brera. The organ shutters and, not least, the main altarpiece, the Virgin in Glory with Saints Sebastian, Catherine and Francis, express the qualities that secured Veronese’s lasting fame: his elegant types, his dazzling highlights and assured use of architecture.

Veronese’s enduring legacy can be experienced nearby. Cross the canal and turn right for the Zattere, with its ever shifting views to the island of the Giudecca and Palladio’s great church of the Redentore. Near a vaporetto stop is the most ambitious church of eighteenth-century Venice, Massari’s Santa Maria dei Gesuati. The ceiling was frescoed by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, whose three compositions perfectly complement the architecture and stucco decoration. For altarpieces the three dominant masters of the time were called in. Sebastiano Ricci’s Pius V with Saints Thomas Aquinas and Peter Martyr on the left is a late tribute to Veronese. This was followed by Piazzetta’s luminous and subtle Saints Vincent Ferrer, Hyacinth, Louis and Bertrand, the restrained colour of which reads almost like a rejection of Ricci’s homage to the Venetian past. Tiepolo’s beautiful Madonna and Child with Saints Catherine, Rosa of Lima and Agnes, above the first altar on the right, is perhaps his happiest statement as a religious painter. The Gesuati perfectly demonstrates that Venice was no artistic backwater when the Serenissima fell so suddenly to the force of revolutionary France in 1797.

Scuola di San Rocco: Jacopo Tintoretto, Nativity.