![]()

MOST visitors approach Siena from the north – the road from Florence – their sense of anticipation heightened by the sight of her great fortress of Monteriggioni, thrown up in 1203 to repel the Florentines. But it is from the south that one has the most memorable views of the city. High in the centre is the great campanile of the Duomo, below it, to the east, the elegant Torre del Mangia of the Palazzo Pubblico. Other churches can be seen above the tremendous circuit of the walls that defined the limits of the early town and defended what was in artistic terms perhaps the most self-sufficient centre of the early Renaissance.

This artistic individuality reflected the political position. Although of Etruscan origin, Siena only became a place of importance in the early medieval period. Long the rival of Florence, Siena was a major commercial and banking centre that jealously preserved her independence and republican institutions. Pandolfo Petrucci gained power in 1487, but his sons failed to ensure the succession and in 1530 Siena fell to the army of Emperor Charles V. In 1552 the city rebelled against his son, King Philip II of Spain. After a long siege, Siena surrendered in 1555, to be granted in 1559 to Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Medici rule was moderately benign, but Siena’s enduring medieval character owes much to the fact that she became a backwater.

The fan-shaped Piazza del Campo is at the heart of the town. The great façade of the Palazzo Pubblico, begun in 1297, is, as it were, the stage set of a wide theatre, its audience the façades of the palaces on the circumference. It was in the piazza that San Bernardino preached his austere message in the mid-fifteenth century, and it is there that the annual drama of that great historic Sienese event, the Palio – or horse race – is still played out. The saint’s badge is seen above the arms of the Medici on the Palazzo Pubblico, which despite the risk of crowds must be visited. In the vast Sala del Mappamondo are two defining masterpieces of Simone Martini, his frescoed Maestà and the extraordinary equestrian portrait of the condottiero Guidoriccio Fogliani silhouetted against an undulating horizon of hills punctuated by bristling fortresses. Equally remarkable are the frescoes of Simone’s contemporary, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, in the Sala della Pace. That of Good Government celebrates the life of the medieval commune: the town is ordered, its territory peaceful and productive. No earlier Sienese landscape offers so compelling a portrait of contemporary agriculture. The fresco of Bad Government is, of course, altogether different in mood – a stark warning of the consequences of anarchy.

As the palazzo was the centre of communal rule, so the Duomo, higher to the west, best approached by one of the narrow streets above the Via di Città, was at the heart of its religious life. The striped Gothic structure must always have impressed those who saw it. It does so still, although the façade sculptures by Giovanni Pisano have been moved to the nearby museum, the Opera del Duomo, and are replaced by copies. After seeing the façades of the cathedral and the incomplete skeleton of what was intended as the nave of its successor, it makes sense to visit the Opera del Duomo. For this now houses most of the components of the epicentral masterpiece of medieval Siena, the Maestà of Duccio di Buoninsegna. This double-sided altarpiece was installed on the high altar of the cathedral on 9 June 1311. The Madonna and Child with numerous saints, raised on a predella, faced the body of the church; on the reverse were scenes from the life of Christ. No Sienese painter for over a century evaded the influence of the Maestà. And it is not difficult to see why. For in this prodigious complex Duccio codified a religious language which owed much to his immediate local predecessors – whose achievement is only now being recognized – and to Byzantine influence, but nonetheless was without precedent in its visual coherence and narrative force. While Duccio did not himself paint all the subsidiary panels and pinnacles, he exercised so close a control over those who did that their individual contributions cannot be determined.

The interior of the cathedral is as arresting as the façade, with the massive banded piers of the hexagonal crossing. Despite the removal of the Maestà – and of Giuseppe Mazzuoli’s baroque sculptures of the Apostles now in London’s Brompton Oratory – the riches of the cathedral continue to astonish. And it is altogether impossible to do justice to these in a hurry. The building is vast, its scale only emphasized by the attentions the Sienese lavished upon it. The wonderful pulpit of 1265–8 in white marble is by Nicola Pisano and represents a development from its precursor in the Pisan Baptistery. The remarkable stained glass of the central rose window was designed by Duccio himself.

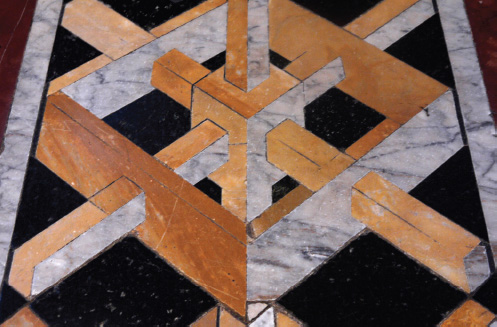

Cathedral: Francesco di Giorgio, pavement border.

Not content with adorning walls, the Sienese decorated the pavement of the cathedral with compositions of inlaid marble. Usually covered, the pavement is now visible for two months from mid-August. The earliest sections are of 1369 and many major artists were involved, including Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Matteo di Giovanni and Neroccio di Bartolomeo Landi, the protagonists of late Quattrocento Sienese art. The designers were responsible not only for their compositions but also for the borders framing these, of which those by Francesco di Giorgio are particularly satisfying. Their High Renaissance successor, Domenico Beccafumi, made a virtue of the challenge the medium imposed: his sections of the pavement, including the Moses striking the Rock and the wonderfully animated decorative friezes, exploit its linear potential to the full. Beccafumi, like other Sienese masters, was versatile. His bronze statues of angels in the choir – with their bases of masks of men with flowing hair – are of a compelling plasticity.

The left aisle of the Duomo is particularly rich. The Petrucci apart, no Sienese family could match the Piccolomini, two of whom became popes, Pius II (1458–64) and Pius III (1503); their altar in the fourth bay is by the Roman sculptor Andrea Bregno, but three of the statues, Saints Gregory, Paul and Peter, are by the youthful Michelangelo (1501–11). It was indeed at Siena that Michelangelo and his younger contemporary Raphael were first in indirect competition. Immediately beyond the altar is the entrance to the Piccolomini Library, commissioned by Francesco Piccolomini to celebrate the career of his uncle, Pope Pius II. The vast frescoes are by the Perugian Benedetto Betti, il Pinturicchio, but, as surviving drawings establish, at least two were designed by Raphael. The compositions are seen through a trompe l’oeil loggia in a perspective that allows for the height at which these are placed. Pinturicchio’s star has faded since the Victorian era but his narrative gifts have rarely been surpassed. Of equal interest are the illuminated miniatures on display in the cabinets below. These have no rivals of their date, the 1460s, and are by two outstanding north Italian masters, Liberale da Verona and Girolamo da Cremona. Of the two, Liberale is the more emotionally intense, Girolamo the more cerebral and conscious of the classicism of Mantegna’s generation.

Leaving the cathedral, follow its east side and go down the splendid flight of steps to the Baptistery. The façade is more austere than that of the cathedral, the interior unexpectedly high. In the font, begun in 1417 by Jacopo della Quercia, one can see how the late Gothic dissolves into the classicism of the early Renaissance. Although only a decade separated Jacopo’s Expulsion of Zaccarias from the companion reliefs by his younger Florentine contemporaries Ghiberti and Donatello, the significance of the intellectual revolution they represented is not in doubt.

South-west of the piazza, on the Via di San Pietro, is the Pinacoteca Nazionale. Modern notions of display have not been allowed to disturb traditional arrangements. The collection of Sienese pictures has no rival. Duccio’s tiny Madonna dei Francescani is followed by significant groups of pictures by Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti and their later fourteenth-century successors. The Quattrocento is represented in depth, with rooms devoted to Sassetta and that idiosyncratic visionary, Giovanni di Paolo; to Sano di Pietro, the most productive native master of the mid-century; to the languorous Madonnas of Matteo di Giovanni and to the lyrical Neroccio. High Renaissance Siena was no backwater. Sodoma, who arrived from Lombardy, was by any standard a major artist, while Beccafumi was a magician both in his lyricism of line and in his use of colour. Spare a moment, too, for their contemporary Girolamo del Pacchia’s beautifully expressed Visitation.

Proceeding south from the Pinacoteca, the road emerges before the much-reconstructed church of San Domenico. On an altar on the right is Perugino’s Crucifixion of 1506, commissioned by the powerful Sienese banker Agostino Chigi, while in the Cappella Piccolomini is what has some claim to be Sodoma’s masterpiece, his Adoration of the Magi. The only other Sienese altarpiece of the time still in situ that rivals it is in San Martino, south of the east corner of the Campo: Beccafumi’s Nativity, which is of a breathtaking beauty, visionary in design and thrilling in chromatic range.

At San Martino you may be alone. This will not be the case in the sanctuary of Saint Catherine to the north-west of the city. The saint died in 1380 and her house was adapted as a shrine in 1464. As John Addington Symonds observed, the sanctuary preserves much of its original character – and on that account alone is a remarkable survival. In the Upper Oratory are a series of pictures of the life of the saint by the most gifted masters of late sixteenth-century Siena, including Francesco Vanni, whose Canonization of Saint Catherine perfectly exemplifies his delicate taste.

San Martino: Domenico Beccafumi, Nativity (detail).

Many of Siena’s major churches lie at or near the extremities of the original urban area: Santa Maria del Carmine with Beccafumi’s Saint Michael; Santa Maria dei Servi with the impressive Madonna del Bordone of 1261 by Coppo di Marcovaldo; austere San Francesco; its more splendid counterpart, San Domenico, high on the ridge above the medieval Fonte Branda, with a constellation of early altarpieces and Sodoma’s persuasive Saint Catherine in Ecstasy; and, opposite the cathedral, Santa Maria della Scala, which boasts the outstanding sculpture of mid-Quattrocento Siena, Lorenzo Vecchietta’s moving bronze of the Risen Christ of 1476, placed alas too high for its subtlety to be easily appreciated. All are worth visiting, not least for the pleasure of walking through the city. So, below San Domenico, is the medieval Fonte Branda. Changes of level mean that almost every turn discloses an unexpected view of medieval brickwork or the façade of a Renaissance palazzo, with so often at least a glimpse of open country in the distance.