![]()

THE most northerly major town of the Tiber Valley, Borgo San Sepolcro lies at the junction of two great historic routes, that from the Romagna in the north to Perugia and eventually to Rome, and the road that crosses the Trabaria Pass to the east, linking the Adriatic coast with the Tuscan heartland. Fought over by local families and powers, and controlled by the papacy for much of the fifteenth century, the town was a major prize when it fell to Florence in 1515.

Massive fortifications attest to Borgo’s importance as a frontier fortress. That the town had long acclimatized itself to Florentine taste is demonstrated by the career of its outstanding artist, Piero della Francesca, whose mentors were Fra Angelico and Masaccio. Piero, so long overlooked, has now been a cult figure for almost a century. His sphere of activity was, to a remarkable extent, dictated by geography. His major commissions were all for places in direct reach of his native town: Rome and Perugia to the south, Ferrara to the north, Arezzo to the west, and to the east Urbino and Rimini. Furthermore, Piero’s Riminese patron, Sigismondo Malatesta, obtained Citerna – hardly ten kilometres from Borgo – which overhangs the cemetery of Monterchi, from which Piero’s fresco of the Madonna del Parto was recently hijacked by the authorities of that town. The prodigious fresco cycle at Arezzo is his grandest achievement. Yet it is surely at Borgo San Sepolcro that he is best understood.

The Palazzo Comunale is sadly no longer entered from the Via Matteotti but from a side door. The visitor is advised to move briskly through the first rooms. Piero’s polyptych of the Madonna della Misericordia was an early commission, although it was not completed until about 1460. The Madonna is of an elevated beauty, and the spectator was not intended to doubt that the citizens and their women who sheltered beneath the mantle were right to trust to her protection. The flanking saints have, perhaps, a more tentative quality, and certainly lack the tension of the Crucifixion which originally surmounted the Madonna and is now at Naples. But it was only in the predella that Piero subcontracted to assistants.

The Resurrection is the symbol of Borgo San Sepolcro – the observant will already have noticed Niccolò di Segna’s Ducciesque interpretation of this in his polyptych in an earlier room. Piero’s celebrated fresco of the subject thus had an especial significance for his townsmen. Our eye moves upwards from the sleeping soldiers to Christ. He rises, as if by an inexorable force, from the sarcophagus, his face at once impassive and serene. Behind stretches the landscape that Piero knew so well, living and verdant on the right, desiccated like that he would have seen on the Bocca Trabaria to the left. Inexorable in logic and timeless in message, the Resurrection is Piero’s absolute masterpiece.

Pinacoteca Comunale: Piero della Francesca, Resurrection, fresco (detail), c. 1463.

Dazed, and perhaps humbled, the tourist leaves. The town has more to offer. Diagonally across the Via Matteotti is the cathedral, with an early copy of the Volto Santo at Lucca, a fine example of the early medieval pigmented wooden sculpture of which so much survives throughout Italy.

Borgo San Sepolcro is laid out on a grid plan. Leaving the cathedral, turn left and keep straight on, until forced a block to the right, passing a particularly fine crumbling palace and other substantial houses. At the opposite side of the town is San Lorenzo, a church that is often closed, but where a nun from the adjacent monastery is usually in attendance.

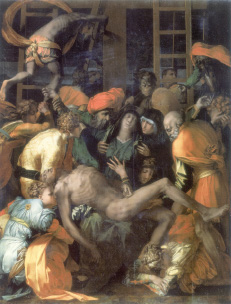

On the altar is a picture that was as compellingly original as Piero’s Resurrection, the Deposition by that visionary genius of the Florentine High Renaissance, Rosso Fiorentino. Like other major artists of his generation, Rosso gravitated to Rome. When it was sacked by the imperial forces in 1527 he withdrew to Umbria, designing altarpieces for Perugia and the miracle church at Castel Rigone, high above Lake Trasimene, and himself painting that of the cathedral at Città di Castello. The Deposition was painted in 1528–30. It is a deeply pondered drama, wrought to an extraordinary emotional pitch, for Rosso’s charged colour is matched by the intensity of his figures. His was a restless spirit which found a supreme expression in this altarpiece, painted for a relatively obscure setting in a lesser provincial town. We are fortunate that it remains there. For the fervent dynamism of the Deposition, reflecting an inner turbulence that must have been sharpened by circumstance, only enhances our understanding of the spiritual confidence of the impassive Resurrection. Both pictures convey that sense of the inevitable which is a characteristic of the very greatest works of art.

San Lorenzo: Rosso Fiorentino, Deposition.