![]()

NO great Italian city is more palpably medieval than Gubbio. The town stands on the southern flank of the Monte Ingino, commanding what must always have been a productive plain. Her Roman past is seen in the much restored theatre below the town and in the Eugubine tablets – laws recorded on sheets of bronze – in the museum. But the city, as we see it, dates largely from the twelfth and succeeding centuries.

Entering by the Via Matteotti, you reach the Piazza dei Quaranta Martiri between the loggia of the Arte della Lana, the wool guild, and the thirteenth-century monastery of San Francesco. Narrow streets rise steeply towards the centre of the town, where the great Palazzo dei Consoli is clearly visible on its terrace; but the main road turns to the left and then bends twice to the right to reach the Via dei Consoli, and its procession of medieval houses with their porte degli morti – doors of the dead – raised above the street level. The pink stone façades reveal their past, as one can see where doors and windows have been blocked and moved.

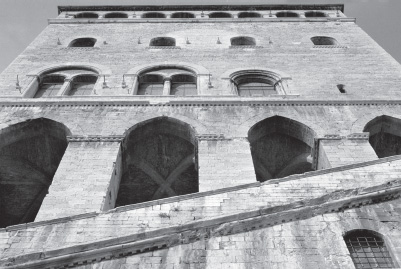

The Piazza della Signoria is the heart of the town, built out over a giant blind arcade. On the right is the Palazzo dei Consoli, emphatically masculine despite its elegant loggia high above. The palace was designed by Angelo da Orvieto and built in 1332. The door opens to a vast hall, from which a narrow stairway mounts to the upper floor, now the civic museum, as rewarding architecturally as for its pictures – for sadly there is nothing by Neri da Gubbio, the Eugubine miniaturist whom Dante consigns to his Inferno. In the archaeological section, the Eugubine tablets have pride of place. On the north side of the piazza is the long neoclassical brick front – oddly thought to be in the English taste – of the Palazzo Ranghiasci. Below this, a passage leads steeply up to the Duomo. An oddly unsatisfactory building, it is most notable for the decoration of a small chapel on the right by an underrated realist of the baroque, Antonio Gherardi da Rieti. Opposite and a little below the Duomo is the ducal palace. The Montefeltro gained the signoria of Gubbio in 1384, and the palace rebuilt by Federico di Montefeltro was a smaller counterpart to that at Urbino. The courtyard remains a space of great elegance, with crumbling facings of grey pietra serena, but the marquetry of the studiolo is in New York, its pictures divided between London and Berlin. Still higher up the hillside is the medieval aqueduct, which can be followed for a mile or so as it curls round the flank of the Monte Ingino to the north-west. The views down over the tiled roofs of the town are memorable.

Palazzo dei Consoli, south façade.

One Eugubine painter, Mello, an early Trecento follower of the Lorenzetti, is adequately represented in the museum of the Duomo and in the Palazzo dei Consoli. A century later Gubbio produced one of the more engaging figures of the international Gothic movement, Ottaviano Nelli. His masterpieces are in two churches on the east of the town. In the Madonna del Belvedere at Santa Maria Nuova the Virgin and Child are seen with angels under a baldachin supported on thin spiral columns up which putti crawl. The fabrics are sumptuous. Nearby, but outside the walls, is Sant’Agostino, whose choir Nelli decorated with episodes from the life of the saint. His narrative is discursive, and his depiction of potentates and their attendants tells us something of the extravagance of contemporary patrician taste.

Sant’Agostino: Ottaviano Nelli, Life of Saint Augustine, fresco (detail).

With the extinction of the della Rovere line in 1624, Gubbio reverted to papal rule. Two churches below the town evoke this period. The elliptical Madonna del Prato, outside the Porta Romana, was decorated by the local painter Francesco Allegrini and has a provincial charm. Eighteenth-century San Benedetto, below the Porta Castello, is of a different order. This too is elliptical. The original furniture is almost miraculously intact. And the high altarpiece, Agostino Masucci’s Immaculate Conception, exemplifies the restrained classicism of early eighteenth-century Rome at its purest; the lateral altarpieces by Sebastiano Conca and Francesco Mancini are equally effective.