![]()

FEW cities are so majestically placed as L’Aquila. It is backed to the north by the dramatic mass of the Gran Sasso and has long been the major town of the Abruzzi. On a roughly triangular site that falls steeply on two sides, the city was founded in 1254, apparently with the approval of the Emperor Frederick II, and reconstructed in 1265 by Charles of Anjou. Although challenged by rebellions and interrupted by invasions by, among others, Braccio Fortebraccio, not to mention the French occupation of 1798–1814, Neapolitan rule endured until the Risorgimento. In 2009 a severe earthquake shattered the ancient city; little is beyond recovery but it will take many years before all the monuments are fully in commission.

Cola dell’Amatrice, San Bernardino.

L’Aquila is rich in medieval churches: Romanesque Santa Maria di Paganica, with the vigorous reliefs of its portal; Gothic San Silvestro, for which Raphael’s Visitation now in the Prado was painted; San Domenico founded by Charles II of Anjou in 1309; and a half-dozen more. All yield in ambition to the great Romanesque church of Santa Maria di Collemaggio south-east of the walls. This was founded in 1287 by Pietro da Morrone, who was crowned here as Pope Celestine V in 1294. The slightly later polychrome façade is striking, and there is an exceptional portal on the north front. In the chapel to the right of the choir is the Renaissance tomb of San Pietro Celestino by Girolamo da Vicenza (1507).

By the time this was commissioned, the church had been overtaken as a place of pilgrimage by the basilica of San Bernardino, to the east of the junction of Via Roma with the Corso Vittorio Emanuele in the heart of the town. Saint Bernard of Siena died at L’Aquila in 1444 and the church was begun ten years later. The confident classical façade, devised by Cola dell’Amatrice, was not built until 1524, and the interior was subsequently remodelled in the baroque taste. On the right is the chapel of San Bernardino, with the saint’s mausoleum by the outstanding local sculptor Silvestro dell’ Aquila, whose earlier monument of 1496 to Maria Pereira and her daughter on the left wall of the choir reflects both Florentine and Roman models.

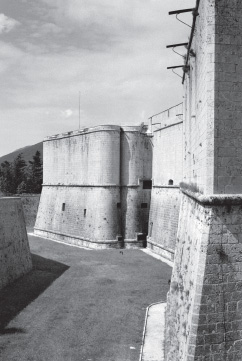

The most assertive building of L’Aquila is the enormous castle at the north-eastern angle of the town, which seems to defy the Gran Sasso that serves as its backdrop. This was built after a rebellion of 1529 to the design of the military engineer Pier Luigi Scrivà, but only completed a century later. The plan is quadrangular, with formidable angle bastions. The castle now houses the Museo Nazionale d’Abruzzo, with comprehensive collections of both sculptures and pictures from the region. There are no outstanding masterpieces, but local artists such as the Master of Beffi and Andrea Delitio deserve to be more widely known.

The most idiosyncratic of the Abruzzesi of the Renaissance was the beautifully named Saturnino de’Gatti. The pictures by him in the Museo Nazionale do not prepare us for the enchantment of his frescoes of 1494 in the parish church at Tornimparte, eighteen kilometres south-west of L’Aquila – and best approached by the ordinary road rather than the autostrada. The choir is decorated with Passion scenes from the Arrest of Christ to the Resurrection, the vault with a vision of Paradise teeming with angel musicians. Saturnino is an artist of ingenuous charm – and I shall always be grateful to Everett Fahy for encouraging me to visit this ‘Sistine Chapel of the Abruzzi’. The church was not affected by the 2009 earthquake.

Medieval prosperity means that there are many fine early churches in the hinterland of L’Aquila, some of which boast early murals. But the most atmospheric site in the area must be the medieval castle of Ocre, fifteen or so kilometres south-east. Begun in 1222, it is surrounded by a well-preserved wall. Within is a chaos of shattered buildings. From the eastern section of the walls one looks directly down on the township of Fossa some 290 metres below: it was over this precipice that San Massimo, the patron saint of L’Aquila, is said to have been hurled in AD 210.

The castle walls.