![]()

TRANI has changed since I first knew it. I arrived at dusk on a festa and it took a good half-hour to get to the harbour. There I parked by a tiny restaurant, whose proprietor directed me to a hotel with the strictest injunction to remove everything that was visible and lock every door. Apulia is safer now. But it has often been a territory where interests clashed, and one still senses a frisson in its architecture.

Trani’s early importance was due to the harbour. Much of her history can still be read from the paved waterfront, with the apse of the elegant Romanesque Templar church, the Ognissanti, hemmed in by lesser buildings. Behind is the core of the medieval town, whose successor spread to the south, its main arteries such as the Via Ognissanti notable for their later palaces. But despite the charm of these, with their rusticated and diamond-studded façades, or the larger buildings at the southern angle of the harbour – the Palazzo Quercia and the Quattrocento complex of the Palazzo Caccetta, not to mention the massive, and much remodelled, castle of Emperor Frederick II that guards the city on the north – it is the cathedral that draws one to Trani.

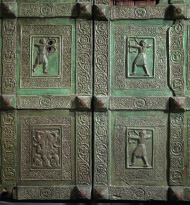

Cathedral: Barisano da Trani, bronze doors (detail), after 1180.

Cathedral: lion support of the west door.

Medieval towns were competitive. The basilica of San Nicola at Bari was begun in 1087. A dozen years later, another Nicola, a pilgrim who had died at Trani, was canonized and work on his cathedral began. The site, above the shore, was that of an earlier church. By the time the structure was completed in the fourteenth century, the original Romanesque scheme had been substantially changed. Time and the restorer have claimed their due, but the first impression as you approach from the west, with the sea to the left, is of an unusually unified structure. The west front expresses the form of the interior, a tall nave flanked by aisles almost equally high raised above a crypt. If you are lucky, the lower door to the latter is open. Otherwise climb the steps to the upper level, where only the back arcade of the original portico survives, and the central door has lost the astonishing bronze doors supplied, perhaps in the 1280s, by Barisano da Trani, but now responsibly moved to the nave. The thirty-two panels of the doors are set in elaborate borders, classical in inspiration; in one, the patron San Nicola Pellegrino is seen with the diminutive artist in adoration at his feet. The vigorous sculpture round the door-case is reasonably well preserved. Above the door is the central arched window, with flanking columns supported on elephants; still higher is a fine rose window. To the right of the façade, improbably raised on a tall Gothic arch, is the great campanile, four-square, of five tiers, punctuated by openings each progressively wider, and crowned by a short octagonal steeple.

Cathedral, from the Mole.

To appreciate the development of the building one should go down to the crypt beneath the nave, and then descend to the higher crypt below the choir. Admirable in its sense of space, this was the first element of the cathedral to be completed. The nave is an archetypal Apulian Romanesque structure of seven bays, supported by laterally paired columns below a triforium of triple arcades set within blind arches matching those below. The main capitals, alas, were destroyed to make way for Corinthian replacements of stucco. These in turn would be swept away when the post-Renaissance decoration was removed in the pre-war restoration. And it is to this restoration that the austerity of the church is owed. The impression is to some extent misleading. For while the bones of the structure were laid bare, its original texture and tonality were beyond recovery, for any counterparts to the admittedly provincial murals in the crypt have long since gone. Whatever has been lost, however, the soaring space remains impressive.

What I love about the cathedral is the exterior. This is magical in the early morning, seen from the mole to the east, as the sun defines the majestic curves of the apses. And as the light moves, so the sharp token buttresses of the lateral façades cast their lengthening or diminishing shadows. For the builders of Trani well knew the visual possibilities of shade in a land of bright sunlight.

Trani has a unique magic. But the city did not exist in isolation. To the south, beyond Bisceglie, is Molfetta where the cathedral by the shore owes much to Islamic architecture, while to the north is Barletta with a rival Romanesque cathedral. Inland at Canosa is an equally impressive cathedral, off the south transept of which is the mausoleum of Bohemund, conqueror and Prince of Antioch, where the bronze doors open to reveal an inscription of telling brevity: ‘BOEMUNDUS’.