The process by which Romanesque transformed into Gothic can be seen as a kind of fifty-year exploration of the aesthetic, engineering and geometrical potentialities of the pointed arch. One of the roots of this transformation is the Norman discovery of the rib vault: as this new feature became de rigueur, its implications began to lead in a new direction. Romanesque was thus transformed from within, even as it reached its maturity.

As well as providing structural reassurance and looking good, ribs had solved some issues widely raised by groin vaults, masking the wobbly lines that often occurred along the groins (and which rejoice in the technical term bastard groin). But they gave rise to new geometrical problems of their own. Ribs run at a diagonal across a rectilinear bay. If one is restricted to semicircular arches, the diameter of the semicircle used for the ribs is inevitably larger than that of the arches on the sides of the bay, and the resulting arches rise to different heights. The vault is thus forced to bow domically upwards in the middle: hard to lay out, and awkward visually. The solution, employed even in the earliest rib vaults, was to distort the arches in various ways. They might be ovaloid or ellipses: but one solution was to break the semicircle in the middle, giving it a pointed profile by generating it from two intersecting curves of larger circles.

Pointed arches thus occur from time to time in buildings that are entirely Romanesque: indeed, they are used in the nave vault at Durham and are a frequent side effect of the interlaced blank arcades encountered against the walls of the more ambitious Romanesque churches (blank arcades, a luxurious invention presaged in the Anglo-Saxon period, would remain a feature of the richest churches throughout the Middle Ages; see pages 18 and 52). But some masons noted that pointed arches have qualities of their own. By varying the diameters of the intersecting circles from which these arches are created, and by moving the centres of these circles up or down, it is very straightforward to lay out pointed arches of different widths but the same height. Such arches may also have been thought to have unique structural properties, sending the weight of the vaults above them more directly into the corner of each bay. The buttresses and bay divisions were thus thought to be doing most of the work of supporting the vault, giving designers the confidence to replace walls with hugely enlarged windows and other openings. Finally, pointed arches had unique aesthetic qualities. A building dominated by semicircular arches has a taxonomic logic to it: the eye reads each arch as separate; it sees the interior as a sequence of great arcs. Large numbers of pointed arches grouped together read as fundamentally alike: the eye perceives unity, and a tense, scintillating harmony results that was the great aesthetic discovery of the twelfth century (see pages 10 and 20).

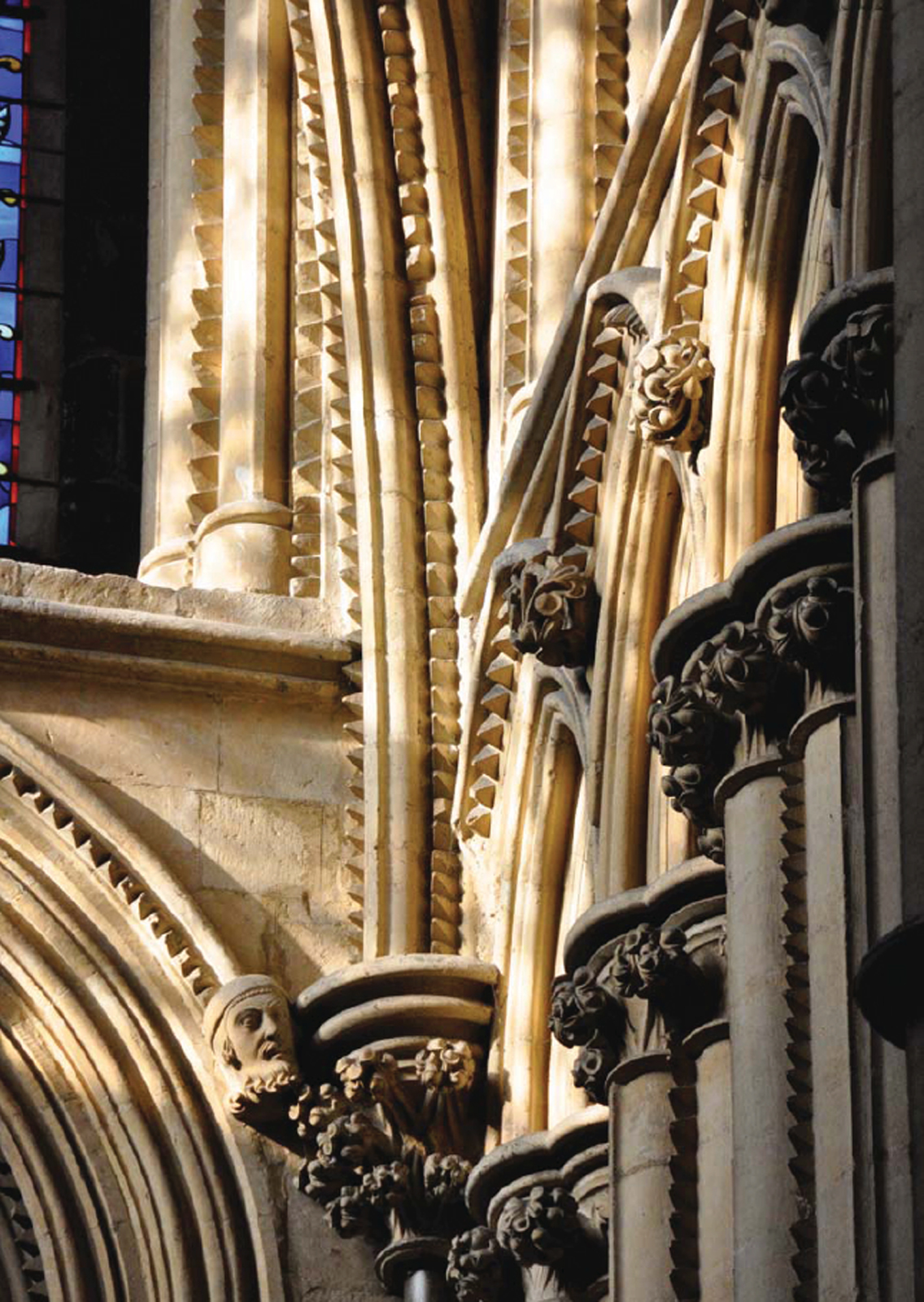

These arches at the west end of Worcester Cathedral (probably after 1175) exemplify the shift towards a lighter, more weightless kind of architecture. They combine a prominent pointed arch with attenuated arrangements of semicircular ones, supported by capitals with deeply cut volutes and curved scallops.

A range of different arch-types have been used to vault the narrow bays of the Romanesque chapter-house vestibule at Bristol: some are semicircular, some are segments of semicircles, some are pointed, and some ovaloid in form.

Masons vied to explore these interrelated potentialities: indeed, a small group working in the Île-de-France as early as 1140 discovered the potential of these ideas within decades of the invention of the rib vault, as can be seen in the ambulatory at Saint-Denis Abbey in Paris. The thrust of the building was sent outwards and downwards on to skeletal arches and buttresses (soon to include arched flying buttresses); walls were replaced by enormous windows and arches; the pointed arch was everywhere. The feel of such buildings was profoundly different from that of anything before; people began to develop new motifs that complemented these effects. The result was a new style – Gothic.

Such ideas spread quickly across the Île-de-France, to other parts of France and across the Channel into England (though there is little left standing here before the 1170s). Experiments in England quickly took these ideas in a new direction. The English, comparatively uninterested in the effects of verticality, harmony, simplicity and light that were the dominant concerns in France, wanted, instead, to created rich, linear, patterned effects, often markedly horizontal, at least by comparison with French work. The new ability to pare walls away was used not to make them thinner but to create layers of decorative motifs. While France continued to be the touchstone of good taste throughout the thirteenth century, this was the first sign of an emphatically English approach to architecture, and the emphasis on ornament and surface pattern would remain.

This period of experiment is often called Transitional or Early Gothic. It is not so much a style as an evolutionary phase. Features are invented that would go on to be diagnostic for the first ‘settled’ Gothic style (Early English); others appear and disappear, enabling one to use them to date buildings. Just as significantly, a panoply of Romanesque motifs, such as the cushion capital and its variants, never seen after the 1180s–90s, or, a little later, the chevron and the semicircular arch itself, were consigned to architectural oblivion, anathema to the new aesthetic. The Transitional ‘style’ is exploratory, experimental: designers had no idea that the colossal window and the pointed arch would dominate design for well over three hundred years, developing in a series of stylistic phases, each a subdivision of Gothic.

The presence of a pointed arch in a building otherwise dominated by semicircular ones is not enough to call a building Transitional, though it is a clue. There need to be some additional signs of stylistic change. But, as a rule of thumb, the more prominent the pointed arches are, and the more other motifs are present that would go on to be seen in Early English, the later the date; indeed, many prefer to call those designs of the 1170s–90s that are plainly Gothic in spirit, but have yet to settle into a defined style, Early Gothic rather than Transitional. Semicircular arches have become rare by the 1190s, and are only occasionally seen from then until about 1220, after which they disappear completely; in any case, by this time everything else, from mouldings to foliage, has profoundly changed.

One diagnostic motif for c.1170–90 is a distinctive form of volute capital, much more delicately carved than its Romanesque predecessor and often apparently modelled on Roman capitals of the Corinthian order. This is a French invention, and a symptom of a wider search for motifs that emphasise weightlessness. Volutes are organic-looking, plant-like features, incapable of supporting anything very heavy, let alone a stone arch; the contrast with the cushion capital could not be greater. This is even truer of the waterleaf capital, with its smooth-sided leaves and tiny volutes. Mostly confined to the north and the eastern seaboard of England, it is the single most straightforwardly Transitional diagnostic motif. Many capitals of the era sit somewhere between the volute and waterleaf. Scallops, especially in the West Country, sometimes take on a curved form known as a trumpet scallop. Meanwhile, while the chevron and its variants continued to be used in the first decades of the thirteenth century (they are gone by about 1220), in the later thirteenth century new motifs, again making such forms lighter and more delicately linear in effect, were developed: of these nailhead (see page 34) would become diagnostic for Early English, taking the graphic energy of chevron but making it lighter, more dynamic in quality. Nailhead then, in contexts where most other features are Romanesque, is a marker of a Transitional date. French sexpartite vaults, in which bays are grouped in pairs, are also seen in a few exceptionally cosmopolitan English buildings, and are diagnostic for Transitional and the first decade or so of Early English.

With its big, broad leaves and tiny volutes, often curling upwards, the brief flowering of the waterleaf capital, seen here at St Mary, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire, epitomises the weightless effects sought by architects as Gothic emerged.

These curving trumpet scallops at Ogbourne St George, Wiltshire, turn into plant motifs, in turn revealing the Romanesque roots of stiff leaf.

A further change took place in the course of the twelfth century. It is at this time that the architectural attributes of the great church (see pages 9–12) were settled, developing only subtly thereafter. Between 1100 and 1200, rib vaults had become de rigueur for great churches; large, vaulted crypts became, and remained, rare; and the upper-level gallery was abandoned and replaced by the triforium. This is merely an attic above the aisle vault: it can result in an elevation in which the middle storey is little more than a row of blank arches – though it can also be massive, with a presence in the elevation akin to that of a gallery (a feature sometimes called a false gallery). The triforium is rare in Romanesque buildings, and the gallery is almost unknown in Gothic ones. Various other defining features of the Romanesque great church (such as the elaborate western complexes known as ‘westworks’ and the multi-towered effects achieved by placing small towers on the corners of aisles and transepts) also disappeared: so few examples of these survive in England that they are not described above. As a result of all this, worship took place on a single storey, and the focus on the east end was even more emphatic; more to the point, the resulting consensus as to which features define the great church would remain in place until the end of the Gothic era in the sixteenth century.

Ensuing changes to this great-church template are few (see pages 75–76), but, as a very rough rule of thumb, triforiums tend to decrease in prominence, and a number of experiments with polygonal plans are seen in the Decorated period, as a result of which apses with polygonal rather than curved ends, not impossible at any Gothic era, make a small-scale comeback.

This latter feature reflects a development that affected churches of all kinds, not only great churches. This was a desire for longer east ends with flat eastern walls, increasing the space around the altar and turning the east wall into an enormous ornamental arrangement of windows. Thousands of east ends were rebuilt from the late twelfth century onwards, and almost all replaced an apse with a longer structure with a rectilinear plan. These east ends also began to hold small stone-built fittings, most commonly the piscina (in which the priest washes his hands before performing Mass; sometimes seen in the twelfth century), sedilia (seats for the officiants at the Mass), and sometimes an Easter sepulchre (which symbolised the tomb of Christ during Easter rituals). Great-church east ends acquired complex rectilinear plans, often with a Lady Chapel extending behind the high altar. All these developments increased the emphasis on the high altar; it is surely no coincidence that the doctrine of the Transubstantiation, in which the consecrated Host is held to be miraculously transformed during Mass, was being promulgated at this time.

A gallery (right, at Gloucester, 1089) is an upper floor to the aisle, large enough to contain windows and chapels; this example is vaulted. By contrast, a triforium (below, at Salisbury, 1220) is nothing more than an attic space.

From the thirteenth century to the Reformation, a piscina (seen, here, between the door to the left and the sedilia to the right) usually stood on the south side of an altar; important altars also had sedilia, usually with three seats, designed in whichever architectural style was prevalent at the time. This Perpendicular example is in the Lord Mayor’s Chapel at Bristol.

This door at St Mary, Ely, Cambridgeshire, is a work of an exploratory era, in which new motifs, old motifs and motifs never to be repeated sat side by side in a single composition.

Lavish use of nailhead – a series of small, sharp pyramids, often running up the side of an arch or a column – at Lincoln Cathedral (after 1237–9).