Chapter 9

PREDATORS, GUARDIANS, AND GRUBS

I needed to take a run.

I’m not a particularly fast runner, nor do I cover dozens of miles at a stretch. I run because I need to get out into the woods, to be alone on a rocky trail, to hear the sounds of the forest without the ubiquitous background hum of traffic and human voices. I also run because if I am stressed out and don’t run, I’m afraid my head will explode.

When we first moved into our house we heard stories about a pair of reclusive but ferocious hawks who nested near one of the trails. They were seen only during the late spring and early summer, but woe betide the unwary hiker or runner who finds him or herself on the wrong trail at the wrong time. A neighbor who lived a quarter mile or so down the road from us had achieved local celebrity status by having his head bloodied several times, events he would recount with a grin and a good-natured shrug.

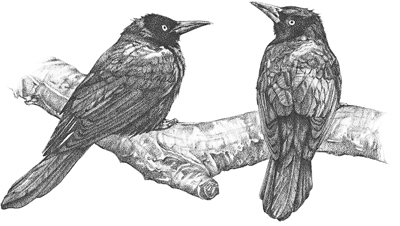

As it turned out, the birds were northern goshawks.

Goshawks, along with Cooper’s and sharp-shinned hawks, are members of the accipiter family, a group of long-tailed, short-winged forest dwellers who prey mostly on other birds. Coops and sharpies can be the bane of a songbird lover’s existence; no dopes, they will occasionally set up shop around a busy bird feeder and simply pick off the songbirds when they appear. Goshawks, on the other hand, avoid developed areas, preferring uninhabited dense woods. Evidently the goshawks figure they’ll stay away from people’s houses as long as people stay away from their woods. But people inevitably fail to live up to this bargain, and the trouble begins.

I knew approximately where their nest was located, so when I went for my run that morning I decided to try to find it. I spotted the large nest, the product of years of additions and renovations, wedged in firmly near the top of a dying hemlock tree forty yards or so from the trail. Woolly adelgids, aphid-like insects unwittingly imported from Japan and first discovered in the United States in 1985, have all but destroyed the hemlocks in much of the East, turning dense green forests into areas so blighted they look like the scene of a forest fire. The goshawks’ territory was still filled with healthy oak, maple, walnut, and birch, but the area surrounding their nest was mostly dead and dying hemlock. Although the trees that once gave them a thick curtain of privacy were now crumbling around them, the goshawks were unwilling to abandon the nest they had used for so many years.

The nest was there, but its occupants were not. I scanned the trees, found nothing, and started to resume my run. I had taken only a few steps when I heard a ringing cry, ascending in pitch and momentum, that silenced the other sounds of the forest: kek-kek-kek-kek-kek-kek!

It was a sound so wild, so stirring, yet so viscerally fear-inspiring that I stopped in my tracks. Those who believe that humans have no trace of wilderness left in their veins should listen to the cry of an angry goshawk, which can instantly reduce the smug descendants of thousands of years of civilization to small, trembling prey. I searched but could not find the source, and I didn’t hear the cry again. Finally, knowing I was being watched, I headed for home.

While most people’s protective instincts are aroused by cuddly creatures such as puppies and ducklings, mine are also triggered by homicidal raptors with records of assault. Although I wanted to go back to the nesting area the next day, I knew that the female would be sitting on eggs and shouldn’t be disturbed. I marked out a month on my calendar; I would return when the eggs had hatched.

In the extra bathroom, the house finch’s wound was healing, and the robin who had lost the bird fight was eating like a prize hog and biting me whenever he had the opportunity. The young redtail had gone off to the Long Island sanctuary, and my first worm delivery had finally arrived.

Most birds eat bugs, so bird rehabilitators must always have bugs on hand. Mealworms come in small, medium, large, and super, the latter being so big that they can actually bite you through your pant leg. Some birds prefer waxworms, which are small, white, soft-bodied grubs that resemble maggots. You can buy a small plastic container of worms at the local pet supermarket for an astronomical amount of money, or you can order them by the thousands from companies such as Grubco or Nature’s Bounty, which charge reasonable rates and will ship them to your door.

I couldn’t resist a company with a name like Grubco, so I ordered 1,000 medium mealworms and 500 waxworms, which arrived in two cardboard boxes riddled with dime-size airholes. Inside the first box was a muslin bag tied shut with a wire twist-tie. Inside the bag were five or six sheets of crumpled newspaper, and within the newspaper were the mealworms. When I held up the bag I heard the sound of soft rustling, like gentle rain.

In the second box were four light blue plastic containers, each poked with airholes and filled with soft wood shavings, and each containing 125 waxworms.

“Kids!” I called. “Come on! The worms are here!”

Mac hurried down the stairs. As he looked at me expectantly, the large lump beneath his shirt started moving slowly across his chest.

“Ouch!” he said. “Get out of there, Zack!”

He pulled the collar away from his neck and a small head appeared, beady eyes flashing. The yellow-collared macaw climbed out of Mac’s shirt and onto his shoulder, eyeing me and laughing giddily, as if he wanted nothing more than to have me join in the fun. I was wise to this little strategy, however; it meant that if I put my hands anywhere near Mac, Zack would rush down like a velociraptor and try to bite my fingers off.

When the kids were toddlers Zack had been relentless, chasing them from room to room and biting them whenever he caught them. “Get rid of that bird!” John said finally, exasperated.

“No way!” I shouted furiously. “Zack was here first!” I ran interference between the kids and the outraged macaw until Mac turned five, when for no apparent reason Zack’s world started to revolve around one of the children he had previously wished only to maim. He treated Mac like a human perch, climbing up his leg, clinging to his belt, and riding on his shoulder; when Mac sat down Zack snuggled under his chin, fluffing out his feathers and grinding his beak in contentment. In the space of a day I went from Zack’s favorite person to his mortal enemy, from the loyal owner of a strong-willed but loving bird to the despised jailer of a homicidal mental patient.

“This is why parrots shouldn’t be pets,” I’d say, removing the hysterically protesting macaw from Mac’s shoulder by sandwiching him between two thick oven mitts. “Only one person in a million can put up with them.”

“Don’t remind me,” said John.

Zack had softened over the last few years and would cozy up to me as long as Mac was not around. Taking him away from Mac with bare hands, however, was still out of the question.

Skye appeared, covered with dirt, at the sliding glass door. “I just built another room onto the kelpie house,” she announced.

Skye’s world was filled with fairies. Her own personal fairy was Marigoldy, who, on certain magical nights, would write tiny notes in tiny handwriting and leave them, colorfully illustrated and accompanied by a real marigold, under Skye’s pillow as she slept. Marigoldy’s friends were the fairies of the clouds, the sun, the rain, the hemlock trees, and every natural wonder, and each one would eventually leave a tiny letter containing a self-portrait, news from the fairy world, and helpful hints on how to deal with the trials and tribulations of first grade. Sometimes the fairy idea well would run dry and suddenly all the fairies would decamp to the moon or the bottom of the ocean, leaving a farewell note saying “Back in a month” and “Bye! We’ll miss you!” Skye would retreat mournfully to the backyard and lavish her energy on the kelpie house, which she was carefully constructing from flat rocks and various pieces of forest flotsam.

Telling the kids about kelpies seemed to me to be a fun way to pass the time and to pay homage to my Scottish ancestors; it was only later, when I watched Skye describe them to a group of friends and their mothers, that I realized why the Brothers Grimm had lost their popularity.

“Kelpies are little men,” she said to her wide-eyed audience. “They’re thousands of years old. Usually they live in lochs in Scotland, but we have one in our pond and his name is Donal MacLeod. If you make friends with him, he’ll tell you all the secrets of the universe. But he keeps his pearls at the bottom of the pond, and if you try to steal them he’ll appear as a giant black horse who is so beautiful you have to climb onto his back, and the second you do, WHAM! He’ll rear up into the air, screaming his rage, and then he’ll drag you down deeper and deeper into the pond until your lungs fill up with water and you drown! And then your hair will turn to seaweed and the crabs will eat out your eyes!”

Skye was delighted, the kids were awestruck, but the mothers’ frozen smiles indicated that my Parent-o-Meter had once again fallen to zero.

“Are you ready for the worms?” I said to the kids. “Mac, you get the fish tank and Skye, you get the food.”

Mealworms need a healthy diet or they won’t do the birds any good, so they are fed a basic mixture of puppy chow, avian vitamins, and several other ingredients that vary according to each rehabilitator. Waxworms are kept refrigerated in the containers in which they arrive; they can go for so long without food that by the time they require it, they have normally already become a food source themselves. We set everything up on the table on the deck, then went to work.

After the fish tank received two inches of mixed worm food, I opened a mealworm bag and slid the crumpled newspapers into the tank. Each time I unfolded a section hundreds of mealworms slid downward, coming to rest in a wiggling, squirming heap.

“Aaaaaggghhhhh!” shrieked the kids, shuddering gleefully and taking turns holding overflowing handfuls of worms.

We opened a container of waxworms so we could scrutinize them, then picked up a few individuals and held them in our hands. Softer and more delicate than mealworms, the waxworms elicited a more restrained response: gentle pokes, followed by long, drawn-out hisses and violently contorted expressions.

“What if Daddy eats them by mistake?” asked Skye, watching as I tucked the four light blue containers into the back of the refrigerator.

“We’ll have to warn him when he gets home,” I replied, chopping up a carrot and an apple and tossing the pieces into the fish tank. “Meanwhile, where should we put the mealworms?”

“They can stay in my room,” offered Mac.

The doorbell rang. “That’s a friend of Maggie’s named Jen,” I said. “She’s bringing us two common grackles. Come on, we’ll just stick the tank in the dining room for the time being, and deal with it later.”

Soon the three of us were walking out to the flight cage with our newest arrivals. I carried two cardboard boxes, while Mac and Skye toted food and water.

“Now remember what we talked about,” I said when we were all inside. “Even though these guys are imprinted, they’re still wild birds.”

“Wild birds think of us as huge predators,” said Mac.

“We have to move very slowly and not stare at them,” said Skye.

“They’ll probably be awfully scared,” said Mac.

“Exactly,” I said, and opened the boxes. Two dark birds hopped out, surveyed the situation with startling yellow eyes, then one flew onto my arm and the other onto my head. I looked up to see the kids staring at me reproachfully.

“They don’t look very scared to me,” said Skye.

The grackles were about two weeks apart in age, still dressed in the brownish black plumage of juveniles. They were clearly surprised to see each other, and equally surprised to find themselves in a 200-square-foot enclosure filled with trees and leafy branches. Within a few moments they were exploring their new surrounding, all the while keeping a close eye on each other. We filled a large shallow dish with water, arranged an appetizing plate of moistened puppy chow, grapes, hardboiled egg yolk, pasta, and live mealworms, then left them alone in the flight cage.

On the way back to the house we stopped and piled onto the hammock, swinging gently back and forth and enjoying what was left of the sunny and peaceful spring day.

“Oh, my God!” came a bellow from the house. “There are maggots in the refrigerator!”

“You’re in trouble again,” said Skye.

“Wait till he gets to the dining room,” said Mac.