Chapter 12

DAYCARE

“Rrrrrrrrrrrrr,” growled Skye softly.

Holding the bug-filled tweezers above her head, she slowly serpentined them down to a tiny eastern towhee, a new arrival who had steadfastly refused to eat. “Rrrrrrrrrrrrrr,” she repeated, and to my amazement, the nestling promptly opened its beak.

“Airplane,” she explained. “Remember, you used to get me to eat by pretending the food was an airplane.”

The kids were out of school and day camp had yet to start, but those carefree summer days were now chopped into twenty-to thirty-minute segments. People would call to say they had found a nestling bird on the ground, and every once in a while I would succeed in getting them to climb into a tree or up the side of their house and put it back in its nest. More often than not there were complications: the nestling had an obvious fracture, the nest was forty feet up, or the bird had appeared out of thin air and there was no nest in the vicinity. If it was a weekend, I could occasionally get the finder to call Maggie or Joanne; more often than not, I would simply take it myself. The nestling would arrive, receive the standard-issue box and towel nest, and somehow join the schedule. I pressed the kids into service, and Skye became a master at getting reluctant babies to eat.

Nagged by guilt that I was neglecting my own children, I’d pack the nestlings into a big wicker picnic basket with a hinged (thus closeable) top, place their food and supplies into a carryall, put the kids’ stuff into a giant canvas bag, then drive to the pool or the lacrosse game. Mac and Skye would race ahead and I’d stagger after them, laden like a pack mule and muttering under my breath, then I’d set up shop under a tree while they expertly fielded questions from the circle of kids who would inevitably gather around us.

“They’re blue jays. Those are finches, and that one’s a cardinal. They eat bugs and dip. They eat all the time. No, you can’t raise one by yourself; you have to have a special license to raise a wild bird. You once gave a baby bird bread and milk? Birds aren’t mammals; they don’t drink milk! No, don’t ever give them water; if a baby bird opens his mouth and you squirt water in, you’ll drown him. If you find a baby bird who fell out of his nest, just put him back; the mother bird won’t care if you’ve touched him, she just wants her baby back.”

Fledglings were a different story. Fledglings are fully feathered and ready to leave the nest, but they haven’t gotten the hang of flying and usually are still being fed by their parents. Often called “branchers,” they hop from branch to branch, occasionally missing their target and falling to the ground. In a perfect world this would not be a problem; they would simply hop around until they found a bush or limb to scramble up, and life would continue. However, thanks to the world of humans, when the fledgling falls to the ground it often encounters a cat, a dog, or a child.

Some of the people who found me through the wildlife hotline couldn’t have been more helpful and concerned. “I can see the parents flying around,” they would say. “I’ve put my dog inside, and I’ve told the kids not to go near that area. What else can I do?”

“You did everything right,” I’d say. “Wait for an hour and check on him. If he isn’t gone, then pick him up and put him on the highest branch you can reach. Then just leave him alone and let the parents take care of him.”

Others made me want to reach through the phone and grab them by the throat. “Oh, I couldn’t possibly bring Mr. Whiskers inside,” they’d say. “He’d be mad at me. Besides, everyone in the neighborhood has cats so if Mr. Whiskers doesn’t get him, somebody else will.”

I tried mightily to find other rehabbers to pawn the fledglings off on, but there simply weren’t enough of us. That first summer I ended up with a collection of fledgling robins, which meant that each morning I could be found bent double, bucket in hand, combing through dead leaves for earthworms.

“I’ll pay you,” I finally said to the kids. “Fill up these containers and I’ll give you each a whole dollar.”

“A dollar!” they said scornfully. “Is that all?” Disappearing into the woods, they quickly reappeared and handed me back the containers. I removed one of the lids, revealing a half a dozen of the biggest earthworms I’d ever seen.

“Jeez Louise!” I exclaimed. “Those are pythons! I want the robins to eat the worms, not vice versa.”

“Up to you,” said Mac, shrugging. “We can get smaller worms, but it’s gonna cost you.”

Wild birds can’t be kept in regular birdcages, as they will damage their feathers by brushing them against the metal bars. To supplement my collection of heavy plastic pet carriers I bought two reptariums—roomy reptile enclosures made of light plastic frames surrounded by soft mesh. Filled with leaves and branches, they provided a safe and recognizable habitat for fledglings who had suddenly been taken from their own environment.

Young birds grow with astonishing speed, and there were mornings when I would peer into a nestful, marvel at their change from the previous evening, and feel lucky and privileged. The kids took their assistant duties seriously and were thrilled with their newly earned right to feed the birds without supervision. Occasionally, however, our inability to locate our dog-eared copy of the nestling identification book caused our conversations to spiral into absurd proportions.

ME: Yup, it’s cute all right, but I have no idea what it is.

MAC: Maybe it’s some kind of warbler.

SKYE: Maybe it’s a woodpecker.

ME: Maybe it’s an elegant trogon.

MAC: I think it’s a blue-footed booby.

SKYE: Nah…it’s a dodo.

ME: It must be some kind of strange dwarf condor!

MAC: It’s a miniature featherless moa!

SKYE: It’s half stork, half beaver!

ME: Let’s try feeding it an enchilada suiza!

MAC: And some Cheez Doodles!

SKYE: I think it wants a chocolate sundae with lots of sprinkles!

How many kids even know what a moa is? I thought triumphantly, somehow convincing myself that my children’s ability to identify an extinct New Zealand ratite was far more important to them than having a mother with a decent amount of free time. The days were hectic but sometimes went fairly smoothly, leaving me with outsized feelings of capability.

Other days did not go as smoothly, leaving me with outsized feelings of inadequacy. As any rehabber will attest, problems tend to come in clusters. One bird will suddenly stop eating, another will develop a mysterious limp, a third will look a little “funny,” and then the telephone will start ringing.

“Can you take a single baby mallard?” asked the voice on the phone.

This was one of the days that were not going smoothly, and I was feeling rather peevish. “A duck!” I burst out. “You must be kidding me! I’m up to my eyeballs in blue jays and robins, and God knows what else, and I’m not even supposed to be doing babies! Out of all the birds I don’t do, the ones I don’t do the most are ducks!”

“Listen,” said the voice. “I must have called every rehabilawhateveritis in the state, and either they tell me they’re full or they don’t answer their phone. We’re leaving for the airport in two hours and if I don’t find somebody to take this duck we’re going to have to just dump him back off where we found him.”

“Take him back to his parents!” I said.

“We couldn’t find them. He was running around by himself. We looked all over for the parents—believe me, we looked everywhere.”

“I don’t have any duck food!”

“There is a feed store two miles from here. I will go in and buy the biggest bag of baby duck food they have. I can deliver the duck and the food right to your door; all you have to do is tell me where you live.”

“No way!”

“Please!”

“No!”

“Please! If you don’t take him he’s going to die! Please! You can’t let him die!”

Eventually I hung up the phone. “‘I don’t do ducks! I don’t have any duck food!’” I chanted nasally, mimicking my pathetic self as I trudged off to my purple three-ring binder to look up “Orphaned Mallards.”

The beauty of baby ducks is that they feed themselves. Unlike altricial songbirds and raptors, whose babies are born blind and nestbound, ducks are precocial; that is, 24 to 48 hours after their birth they’re wide-eyed and racing around after their mothers. This made me feel better, as did the fact that the incoming duckling wasn’t a wood duck. I had learned through the grapevine that most rehabbers live in fear of getting wood ducks, who are so shy and reclusive that they drop dead from sheer terror if you so much as glance in their general direction.

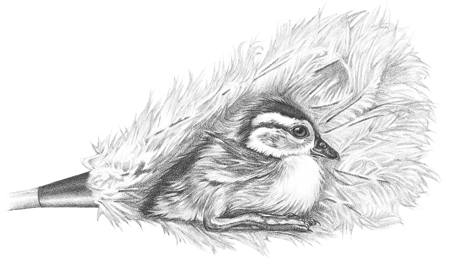

I went off to prepare a duck box, suddenly filled with gratitude toward the rehabber friend who had insisted on giving me a feather duster “just in case,” even though at the time I had insisted that there was no way I would ever need one. A duck box is a large shoebox with the lid attached on one side, allowing it to be easily opened and closed. An entrance hole is cut into the front. Another hole is cut in the top (the ceiling), into which is stuck an old-fashioned feather duster, so the feathers are in the box and the handle sticks out of the ceiling. A heating pad covered with a terry cloth towel is placed on the bottom, then the whole contraption is placed into a large topless cardboard box. The end result is a nice roomy enclosure, complete with a little house the duckling can run into if it’s cold or scared. The heating pad provides warmth, the feathers are an approximation of a mother duck. I put the whole thing on the washing machine, closing the folding doors just as the front doorbell rang.

A young couple stood outside the door, both wearing apologetic but determined expressions. The woman held a small canvas carryall, the man a very large bag of Unmedicated Game Bird Starter. Wordlessly, the woman opened the carryall.

I looked in. Staring back at me with an apprehensive expression was the tiniest duck I’d ever seen.

“Oh God,” I croaked. “Are you sure you looked everywhere for the parents? Everywhere?”

“I swear to you,” said the man, solemnly raising his right hand. “We looked everywhere.”

I carried the duckling into the kitchen, where John and the kids had materialized. The tiny duckling’s appearance caused a waterfall of elongated vowel sounds, with only one family member withholding approval.

“Aaaaaaaaaah!” breathed Skye.

“Oooooooohh!” sighed Mac.

“Awwww!” crooned John.

“War!” shouted Mario.

We all looked at each other.

“I’ve never heard him say that before,” said Mac.

“Maybe African greys don’t like ducks,” said Skye.

I put the duckling in the box and gave it a small tray of soaked food, which, after some encouragement, it ate eagerly. Afterward I opened the lid of the house, placed the duckling on the nice warm towel, and fluffed the feather duster around it, then closed the lid. There was a moment of silence, then a soft peeping.

“I’m going to name her Daisy,” said Skye.

“Daisy!” snorted Mac. “No way.”

“What would you call her?” Skye demanded. “Brutus,” she intoned deeply. “Lothar.”

“You know something?” I asked. “I’m not sure that’s a mallard. I think it looks kinda funny.”

“What do you mean, ‘kinda funny’?” asked John.

“It’s a scientific term,” said Mac. “I’ll explain it to you when you’re older.”

The peeping grew in volume and intensity. Soon the peeps were accompanied by soft thuds as the newly christened Daisy began attempting to hurl herself out of the box. From our various positions we could see the top of her head appear, then disappear, then appear again. Finally she levitated straight up and somehow landed on the rim of the box, where she teetered wildly before pitching off toward the bare floor five feet below. Before I knew what I was doing I’d thrown myself across the room like a star football receiver, landing flat on the floor and catching the duckling just before she hit the ground. I lay there silently, wondering if I’d broken any bones.

“Nice one, Mom!” came the appreciative chorus. “Do it again!”

Soon the duckling was back in the box. The box now sported a top made of metal hardware cloth, the same material that encased the flight cage. As I listened from the living room I could hear Daisy’s levitation efforts being thwarted by the wire top. Bonk! Peep, peep, peep. Bonk! Bonk!

“Awwwwww, she’s lonely!” called Skye, picking up the ringing telephone and disappearing into her room.

She was lonely, all right, but it was seven at night and I didn’t have any other ducks to keep her company. I covered the box with a towel, thinking the darkness might calm her down and make her sleepy. No dice. I continued to listen to the steady drumbeat of Daisy’s head against the top of the box, desperately hoping she’d settle down before she gave herself a concussion or died of stress. Bonk!

I returned to my bookshelf but found no information on what to do if your single duckling adamantly rejects the duck box you have so painstakingly put together. My instinct was to comfort her and deal with imprinting later, but then I envisioned Daisy as a mature duck irreparably bonded to humans, living in a miserable gray half-world, a pet but not a pet, a wild duck but not a wild duck, her dire fate inarguably my fault. I’ll just leave her in the box, I thought, then envisioned the tiny, terrified duckling bereft and abandoned, finally dying a lonely death from the large dent she’d put in her own head. Either way I was headed for Rehabber Hell. Rehabber Hell materializes around your bed at two in the morning, when you lie awake and catalogue—bird by bird—all the rehabbing mistakes you’ve ever made, both real and imagined, and inevitably conclude that you are nothing but a drunk driver careening wildly through the helpless bird community. This is one reason rehabbers always look so tired, even during the off season.

Finally I couldn’t take it anymore. Knowing I was destined for Rehabber Hell no matter what I did, I strode into the kitchen, scooped up the frantic duckling, and marched back into the living room, where Mac sat engrossed in The Seven Songs of Merlin. I deposited Daisy under his chin. Without taking his eyes off his book he cradled one hand around her, and Daisy nestled in with a blissful sigh and instantly fell asleep.

A half hour later Mac deposited the groggy duckling in her feather-duster bedroom and silence ensued. Perhaps, I thought, this was all she needed to get to sleep. I’d find another duckling for her tomorrow, she wouldn’t imprint, and I’d be saved from eternal damnation. Feeling very pleased with myself I readied the kids for bed, then sat down with John to watch The Sopranos.

During its heyday we considered The Sopranos sacrosanct. Most television is so awful that the Mafia drama was one of our only forms of serial entertainment. John and I would go to ridiculous lengths to avoid being out of the house on Sunday nights, and we spent inordinate amounts of time deconstructing the characters’ motivations and speculating on the details of their eventual demise. At the stroke of 9:00 on this particular Sunday night we were in our usual positions: draped on the couch, wineglasses in hand, grinning with anticipation. Just as the theme song started to play, however, there was an unexpected accompaniment.

Peep. Peep. Peeppeep. Peeppeeppeep. Peeppeeppeeppeeppeeppeeppeep Bonk! Bonk! BONK!

In that split second a decision had to be made. But factoring in The Sopranos made it surprisingly easy. I raced into the kitchen, and before the theme song ended I was back on the couch, wineglass in hand, duckling carefully ensconced under my chin.

With my luck it happened to be the episode in which Christopher (pronounced Chris-tu-fuh), the psychotic young lieutenant, tells Tony, the mob boss, that Christopher’s slinky girlfriend Adriana has just admitted to spilling her guts to the Feds. Tony gets his soldier Silvio to drive the unsuspecting Adriana to an upstate hospital, where Christopher is supposedly clinging to life after a baffling suicide attempt. The whole thing is a setup, of course, and before you know it Silvio has pulled off the highway into a deserted wooded area, where Adriana instantly realizes the jig is up.

Now I always had a soft spot for Adriana, who was rather dim but essentially had a good heart. She’d sashay across the screen wearing a catsuit, four-inch heels, and a black eye from her latest encounter with her loutish boyfriend, and I’d wish I could rescue her, put her in my flight cage for a month, and set her free. But it was not to be. As I lay mesmerized on the couch Silvio jumped out of the car, opened the passenger door, threw Adriana to the ground, and pulled out a giant silver gun. Forgetting all about the duck under my chin I sat bolt upright and, embarrassingly enough, actually shouted “Look out!” to the doomed Adriana. This propelled Daisy, suddenly wide awake and peeping hysterically, through the air and into a cushion at the other end of the couch. John leaned forward and picked her up, his eyes still glued to the screen.

“Here,” he whispered. “You dropped your duck.”

Daisy’s sudden launching must have tired her out, for the rest of the night passed uneventfully. First thing in the morning, filled with foreboding, I tiptoed to the box. I opened the lid of the duck house and there she was, definitely alive, snuggled under the wing of a soft toy duck that Skye had donated to the cause. All I had to do now was scare up some more ducklings, and I’d be home free.