Chapter One

God Is Going to Trouble the Waters

Wade in the water

Wade in the water, children

Wade in the water

God is going to trouble the waters.

— Traditional

Thus far it was an uneventful autumn evening on the grounds of Alexander Somerville in Calvert County, Maryland. By Isaac Brown’s account, he was with his family at his own home, three miles distant from the home of his master. He was considered to be quiet and loyal, so much so that he had been given the supervision of his owner’s more remote plantation on which he lived. Although of the average height at five feet eight inches, he was powerfully built and his physical presence as well as his temperament had made him an ideal candidate for his position. Married to Susannah, a free woman, and the father of eleven children — all free because they assumed the status of their mother — he had outwardly appeared to be content with his lot. He was a part of a much larger black community whose member’s occupations were farmers, carpenters, mechanics, servants, sailors, fishermen, and oystermen who plied the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, the Patuxent River and Chesapeake Bay. In the immediate district of Calvert County in which he lived, the number of slaves and free persons was almost equal. When the roughly three hundred free blacks were added to the number of slaves, the blacks outnumbered the whites.[1]

It was a beautiful, natural setting — rolling hills, small ravines, and tall forests. Tobacco, the king crop of the area, was grown on the flatter plateaus. Along the coast of the Chesapeake, beautiful beaches and high cliffs offered an impressive view of Maryland’s distant Eastern Shore.

The lord of the lands had much to enjoy in his domestic and business life. Somerville’s family had come a long way since his earliest ancestor arrived in the New World more than a century earlier. He was sent as a prisoner to be sold as an “indentured servant,” exiled from his native Scotland for taking up arms to attempt to return the Stuarts to the British throne.[2] The generations of the family had prospered in the ensuing years, acquiring wealth, property, and an elevated status in the county. Alexander continued to build upon that familial foundation. In 1840, five free blacks lived on his farm: three children and two adult women, who would have served as domestic servants. Another white couple also lived on the premises, presumably the overseer and his wife. Along with them were thirty-three slaves of both sexes and a wide range of ages. Most of them worked on their owner’s farms, however, two worked on vessels in the nearby waterways. Within a decade despite the departure of some by sale or by death, the number of slaves would nearly double.[3]

Somerville’s wife, Cornelia Olivia Sewell — commonly referred to as Olivia — had a very interesting family history of her own. Her mother’s family, who were of Swiss heritage and Mennonite faith, were among the earliest settlers of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. When Olivia’s parents were married, her father, Charles Sewell, moved from his home in Maryland to his bride’s house in Pennsylvania, bringing several slaves with him. According to terms of Pennsylvania’s 1780 Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery “persons passing through or sojourning in this State” could retain their slaves no longer than six months.[4] Sewell followed the example of many others by returning to Maryland with his slaves for a few minutes each time the six-month anniversary approached, technically allowing him to retain his chattels ad infinitum. Once the state legislature tightened up that loophole by amending the Act in 1788, Sewell manumitted at least two of his slaves with the stipulation that they become “indentured servants” and serve him for another seven years. Sewell also attempted to evade the spirit of another term of the Act by registering the infant children of these “indentured servants” as slaves until the age of twenty-eight.[5]

These subterfuges were noticed by William Wright, an anti-slavery activist who belonged to the Society of Friends. Wright carefully charted the elapse of time between Sewell’s visits to Maryland and immediately initiated a court case to have the slaves declared free when their master missed a six-month deadline. Sewell was enraged when the court freed his property and chased Wright at full gallop, occasionally striking the fleeing Quaker with a rawhide whip. However, no amount of physical retribution could reverse the ruling of the court and the disgusted Sewell soon sold his wife’s land in Pennsylvania, packed up their belongings, and returned to Maryland to raise Olivia and his other children in a state where no such anti-slavery laws existed.[6]

By October 23, 1845, Olivia and Alexander Somerville were soon to celebrate their thirteenth wedding anniversary, which would take place on the sixth of the following month. Their young family was growing — Charles, their eldest, was twelve, Mary Elizabeth was nine, and Alexander Jr. was a toddler of two. With supper finished, most of the family was in another part of the house. As the shadows grew longer at the end of the day while his servant girl cleaned the supper dishes from the table and his daughter Mary played on the living room floor, Somerville reached for the newspaper and settled into his chair to relax and catch up with the happenings beyond the confines of his family farm. His interests were varied, having served as a county representative to plan a grand commemoration of the landing of first Europeans on the shores of Maryland, a trustee to establish an academy in the neighbouring town of Prince Frederick, and a vice-president of the state’s temperance society. Although it is unclear if he did so from motives of benevolence to give them a homeland of their own or if it was to remove those whose liberty served as a disruption to the minds of the enslaved, he had even pledged money to the Maryland State Colonization Society to assist in building a vessel to send free blacks to a colony in Liberia.[7] The newspapers carried many regular advertisements as well as stories from a variety of sources from across the country and occasionally across the ocean.

Isaac Brown’s mistress, Cornelia Olivia Sewell Somerville, and his master, Alexander Somerville, were leading citizens in Calvert County. According to the Baltimore Sun of February 7, 1845, the governor of Maryland had appointed Alexander to the Orphans’ Court, which settled wills and estates, including the appointment of guardians for minor children. He also had once been a Whig candidate for the State Legislature. From A History of the Kägy Relationship in America from 1715 to 1900, (1899).

Courtesy of Milstein Division of United States History, Local History & Genealogy, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Image ID: 2044111.

With his attention focused on the open pages before him, Somerville did not notice the barrel of the gun that silently slid onto the sill of the open window. The gun was loaded with large squirrel shot that was designed to bring down small game, but was potentially lethal to much larger prey. Without warning, the trigger was pulled and the newspaper instantly shredded in his hands. As it was intended to do, the squirrel shot scattered, striking its target in the shoulder, neck, roots of the tongue, and side of the head. The wounds were extensive and severe and the doctors who were immediately summoned had little hope that Somerville could survive.[8]

The overseer was quickly summoned, but as he approached the house he reported that he heard the firing of another gun, and, fearing that he was the intended mark, dove for cover, thereby missing the opportunity to see the shooter. When the panic finally subsided somewhat, the overseer entered the main house. When his employer was able to gather the strength to whisper, he instructed the overseer to go to Isaac Brown’s house to ascertain if that slave was at home. Although he had not seen the gunman, he had the suspicion that it may have been Brown. Still shaken and fearful of his own safety, the overseer sheepishly declined to do as he was bid.[9]

Word of the attack rapidly spread throughout the rural neighbourhood. Rumours of slave uprisings and violent mutinous retributions frequently caused waves of uneasiness among whites throughout the South. Before long, an armed posse assembled to track down the culprit and to apply swift judgment. It was not reported if there was any recent cause to conclude Brown’s guilt, but Somerville was very much aware that he had reneged on his promise to give Brown his freedom upon reaching the age of thirty-five. And, of course, it would have been common knowledge that Somerville had taken the life of Brown’s brother and had neither been arrested nor tried for his crime. According to the law, blacks who may have watched the stabbing were not allowed to testify and there were no white witnesses. Somerville had effortlessly gotten away with murder. Now, the evolving pervasive thought was that, although it was a dish served cold, Brown had finally taken his revenge.

Isaac Brown gave a very different account. He swore that he was innocent of the charge and that he was, as others could confirm, at his home. It was only upon hearing of the shooting that he quickly left his house, jumped onto his horse, and made haste to his master’s dwelling. While en route, he met with a group of armed men who took him into custody and carried him to the county jail at Prince Frederick.

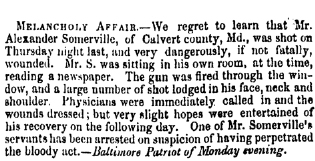

The notice of the assault on Alexander Somerville was widely reprinted in several parts of the country, including the one shown here, printed in the Baltimore Sun on October 29, 1845.

Library of Congress Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room.

Newspapers from around the country rushed to print the sensationalized story. Readers of The Baltimore Patriot, The Boston Daily Patriot, The New York Herald, and Gettysburg’s Star and Republican Banner were among those shocked by the details. Even the premier national anti-slavery newspaper of the day, the Liberator, reprinted the story under the heading ASSASSINATION. The November 1, 1845, edition of the Maryland Republican from Annapolis reported: “The circumstances, as related to us, are very strong, and will, no doubt, be sufficient to convict him.” It appeared that Isaac Brown’s guilt had already been determined.