Chapter Eleven

Something to Hope For

Most interesting of all, are the inhabitants. Twenty years ago, most of them were slaves, who owned nothing, not even their children. Now they own themselves; they own their houses and farms; and they have their wives and their children about them. They have the great essentials for human happiness; something to love, something to do, and something to hope for.[1]

— Samuel Gridley Howe, Boston, 1863

Somewhat surprisingly, as the newspaper article suggested, Isaac Brown chose to permanently adopt the name “Samuel Russell” that he had assumed after his successful flight from slavery. Surprising, considering that this alias was widely known after having been revealed in Philadelphia courtrooms and printed in dozens of newspaper articles. Anyone who might still be doggedly pursuing him would not be fooled by this transparent change. Other runaways changed their names multiple times in the attempt to erase any tracks they may have inadvertently left behind. Some of those later reverted to their original name after the emotional intensity of their experience subsided somewhat and they began to breathe a bit easier as they adjusted to their new reality. The decision that Isaac made had to be enormously difficult — relinquishing the name that he had been known by for most of a lifetime, the name that his parents, siblings, and many kinsmen carried in Calvert County. And of course, “Brown” was the surname of his wife and his many children.

On the other hand, perhaps making the choice may have been less monumental than one might think. After all, it was part of Isaac’s own self-assertion and reconstruction as a new man, as his own man. However, despite whatever internal conflicts may have come into play, the patriarch of the family shed both his Christian and his family name. His immediate family took a less dramatic compromise; Susannah Brown became Susannah Russell and their children — from twenty-year-old Lucinda to baby Rebecca — likewise adopted the surname Russell.

The older children would have been able to find work in the surrounding fields or as common labourers or house servants and contribute to the family’s finances, thereby freeing them from the humiliation of having to depend upon the largesse of others. This would help distance them from the raging controversy called “the begging system” that split the black Canadian population, many of whom proudly wanted to proclaim to a doubtful world that they were perfectly capable of being independent and self-reliant once given the chance.

The Brown — now Russell — children would also quickly reach the age where they could start out on their own and begin their own families. Lucinda was first when Wesleyan Methodist minister, Reverend Samuel Fear, after publishing banns inquiring if anyone knew of any impediment to her proposed nuptials, joined her in marriage to Richard Nevils on August 30, 1849.[2] It is documentation of Lucinda’s wedding that gives the first real hint of where the Russell family lived after leaving Dawn. The ceremony took place in Harwich Township, which partially surrounded the town of Chatham to the southeast. It is interesting to note that although the bride and the two witnesses, Jason Grant and Mary Jane Gibson, were black, the Nevils family, who were of Irish descent, were white.

In his 1855 Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro: His Anti-Slavery Labours in the United States, Canada, & England, Samuel Ringgold Ward, a travelling lecturer for the Anti-Slavery Society of Canada, gave his thoughts on Edwin Larwill (shown above) and on the behaviour of some Chatham residents towards him (see full quote in Chapter 11 notes): “I must be allowed to express my regret that some of the black men of Chatham — men, too, of wealth and position, as compared with many others, white and black — are wanting in manliness. They do not bravely, manfully, stand up for themselves and their people as they should. They cower before the brawling demagogue Larwill — a man well known as an enemy of the Negro, but a man beneath any manly Negro’s contempt — a recreant Englishman, of low origin but aspiring tendencies, not knowing his place, and consequently not keeping it.” [3]

Courtesy of Buxton National Historic Site & Museum.

The couple were no doubt the target of a great deal of criticism because, at the time of their wedding, Chatham was notorious for its racial divisions, and, due to the pending prospect of a large number of blacks moving into the nearby Buxton Settlement, feelings were reaching a fever pitch. Despite flowery references by visitors to the town, the welcome mat was not laid out for blacks who sought to make Chatham their home. Intermarriage would have certainly have raised an outcry. The widespread anti-black movement was led by Edwin Larwill, a local politician, newspaper editor, and tinsmith, who, along with other prominent men, organized meetings, wrote newspaper articles, posted handbills, and circulated petitions to protest the further introduction of blacks into parts of the province where whites already lived.

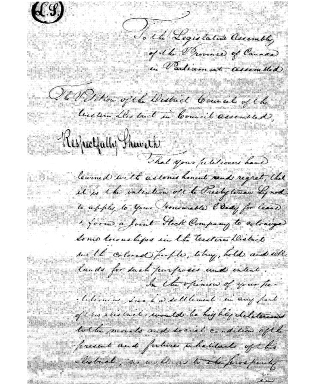

The petition sent to the Legislative Assembly of Canada, February 19, 1849, protested the settlement of Blacks in the district on the grounds that it “would be highly deleterious to the morals and social condition of the present and future inhabitants.”

Library and Archives Canada, William King Collection, R4402-0-1-E.

One such petition, addressed to the Presbyterian Synod and signed by three hundred citizens, who, on the one hand, professed that they “will not for one moment question the pure and Philanthropic Motives which have prompted you to step forward and assist in ameliorating and improving the condition of the Colored Man, as men, we have no objection to their enjoying every privilege and Rights, Religious, Moral, Political, and Social …” but on the other, explicitly spelled out their true feelings:

The Negro is a distinct species of the Human Family and, in the opinion of your Memorialists is far inferior to that of the European. Let each link in the great Scale of existence have its place; the white man was never intended to be linked with the black. Amalgamation is as disgusting to the Eye, as it is immoral in its tendencies and all good men will discountenance it.[4]

Despite this poisoned atmosphere, Lucinda and Richard Nevils braved the opposition, taking comfort in the company of Chatham’s black community whose numbers would soon increase dramatically following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 when thousands of American refugees, both runaways as well as legitimately free, fled to Canada. They came to escape the terror of that law whose terms mandated the return of fugitives who had fled to any part of the union, demanded that ordinary citizens participate in their capture, and refused the right for blacks to testify in their own defence. In effect, officials were encouraged to disregard the kidnapping of free blacks who were destined to be sent to the South as slaves.

The passage of that law removed any thought that might have lingered for Lucinda’s father to ever return to the country of his youth. Despite dogged unsuccessful attempts to pinpoint the exact location of the entire Russell family during their first few years in Canada, given the location of Lucinda’s wedding, it is probably safe to assume that they lived in or around Chatham. Proof positive does not appear until eight years later, when, in the summer of 1855, the name Samuel Russell prominently appeared in the Provincial Freeman, an abolitionist newspaper that had just moved from Toronto and resumed publication in Chatham.

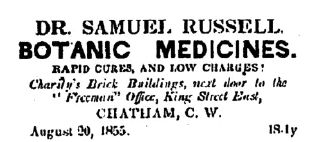

Samuel Russell regularly advertised his medical practice in the Provincial Freeman. This ad is from the September 15, 1855, edition.

Courtesy of Chatham Kent Museum.

It appeared that Samuel had begun to prosper, and, being in the healing profession, was no doubt a respected member of the community. His office was in the impressive red brick Charity Building on the southeast corner of King and Adelaide Streets. It was owned by James Charity, a shoemaker who kept upper-floor apartments that could be reached by staircases in the rear of the building. The ground floor was divided into four shops, with Charity’s shoe store facing the street corner. The two adjoining offices of Mary Ann Shadd and her brother Isaac, one of which they used for their Provincial Freeman newspaper and the other for their printing presses, were on the opposite side of the building. In the centre of the structure was Dr. Russell’s office, identified for passersby with a hanging sign in the front and a green curtain stretched across the window for privacy.[5]

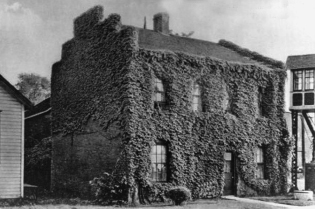

he Charity Building in Chatham, which housed the medical practice of Doctor Samuel Russell and the offices of the Provincial Freeman newspaper, as it looked in the mid-nineteenth century.

Courtesy of Edward and Maxine Robbins.

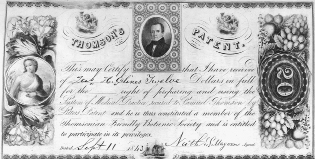

Samuel Russell was commonly known by occupation as a “root doctor.” These practitioners were common in the South where roots, herbs, and various folk treatments were plentiful, but scientifically trained doctors were not. Perhaps in the “Negro quarters” in Calvert County, Maryland, a younger Isaac Brown had been instructed, or least observed which plants to use to cure certain ailments. Perhaps the tradition had been passed down from African ancestors, or learned from Native Americans, or simply came into common usage by trial and error and necessity. Whatever the genesis of his interest in this vocation, by the time he set up his own practice he was a disciple of Samuel Thomson, who had developed a popular method of medical practice. He published numerous volumes as well as revisions and additions to introduce devotees to his theories and practices, including a work on anatomy, recognition and treatment of diseases, and sections on botany. Thomson had numerous travelling agents who sold the patent for his work, as well as the natural products such as cayenne peppers, hemlock, mustard, ginseng, red clover, turpentine, ginger root, and the exotic-sounding Balm of Gilead for use in treating patients.

In order to qualify to practise the Thomsonian system of medicine, Samuel Russell would have to pay his fee, whereupon he would have received a similar certificate as pictured above.

Courtesy of Lloyd Library and Museum, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Before plying his new trade, Samuel Russell would have to subscribe to the theory that “all diseases originate from … the deranged state of fluids in the body, by the absence of heat, or loss of vitality; which produces an over pressure or excess of circulation to the head, and a proportionate deficiency in the feet. This creates derangement in the organs of sense, and a proportionate want of action with the digestive apparatus.” Although there were many different medicines recommended for various ailments, no matter what the disease, the Thomson physicians were to always begin their treatment by “Equalizing the Circulation”:

In the first place, put the feet of the patient into water as hot as can be borne, increase the heat by adding water of a higher temperature until a copious perspiration is started on the forehead and in the palms of the hands; the patient may be in the bath if thought necessary; this will afford some relief. Then take brown emetic, cayenne, composition, and nerve powder, of each one teaspoonful, put them into one pint of boiling water and let them steep for ten minutes; sweeten with molasses, and let half the quantity be given as an injection, as hot as it can be borne, and let the patient retain it as long as possible. This will turn the excitement from the head downwards and sickness at the stomach will be produced. Then give a table spoonful of the tincture of lobelia and a small quantity of cayenne, in some simple tea, and if this does not produce sufficient vomiting repeat the dose. The vomiting will be easy, the veins in the hands and feet will be filled, the head, in consequence of the equalization of the circulation, will be relieved, and the whole system will become quiet and easy.[6]

On October 12, 1855, within weeks of his advertisement first appearing in the newspaper, Samuel Russell “root doctor” and his wife Susannah purchased a home and small lot, thirty-two feet wide by one hundred feet deep, on the southwest corner of King and Adelaide, directly across the street from his place of business. The couple bought their new home from local carpenter John Fleming and wife Mary, for 178 pounds, fifteen shillings. The Flemings agreed to hold the mortgage for the full amount with the ambitious repayment schedule to be thirty-seven pounds, ten shillings on December 1, 1855, another thirty-seven pounds, ten shillings April 1, 1856, fifty pounds on October 12, 1856, and the final fifty-three pounds, fifteen shillings on October 12, 1857. In order to make the transaction official — just as he had done in 1847 when the fugitive slave Isaac Brown gave his statement to a Pennsylvania court — Samuel Russell, even though he was perfectly capable of doing otherwise, signed the document with an X.