Chapter Thirteen

The River Jordan Is Muddy and Cold

The river Jordan is muddy and cold

Well it chills the body but not the soul

All my trials Lord soon be over

— Traditional, arranged by Peter Webster

In 1857, Samuel Russell decided to make a major move. His medical practice was not as lucrative as he had hoped and it was difficult to meet his obligation of paying the mortgage on his Chatham home. The total amount of 178 pounds, fifteen shillings, was to be paid in full by October of that year. With twenty shillings in a pound, that meant that he owed 3,575 shillings altogether. Even if the children contributed, it was an almost impossible task. Sixteen-year-old Jacob and older brother Leonard were common labourers who could only earn from six to eight shillings per day, and there was never a guarantee on how many days they could work. If they found seasonal work with a farmer outside of town and had to board, their pay would only be a little over three shillings per day. If they found a permanent job as a household servant, they might receive seventy shillings for a month’s work. Lucinda and Catharine had their own households to concern themselves with and could ill afford to support their birth family. Even on days that William, Nancy, and their slightly older sister may have taken off school and found an odd job, at their age they could only expect to make one shilling and ten pence (twelve pence in a shilling).

Some people were now using dollars instead of the old British currency, where 35.5 shillings was the equivalent of one United States dollar, but no matter, expenses always seemed to exceed income.[1] Samuel’s medical practice faced stiff competition from the other black doctors in the area, all of whom appeared to enjoy a higher status in the community. Money was also tight with many would-be patients. Even his office-building mates at the Provincial Freeman constantly struggled financially and even advertised that they would accept produce in lieu of cash.

With financial calamity looming, the Russells had only to look for possible relief a few short miles away, to the large unsettled Crown lands known as the Raleigh Plains, just west of Chatham and south of the Thames River. The banks of the Thames were long-settled by United Empire Loyalist families who had been granted land in the latter part of the eighteenth century following the American Revolution. Some of them had brought their slaves with them at the time when slavery was still legal in this British colony. After slavery was abolished in 1834, some of them remained and lived among those Loyalists and their descendants, which included the family of Captain John Drake who had been involved in the transatlantic slave trade from the Guinea coast of Africa to the New World before the trade was outlawed in 1807.[2]

A view of King Street in Chatham as it looked in the 1850s.

Courtesy of Chatham Kent Museum.

The Raleigh Plains were also immediately north of the Buxton Settlement. Three thousand of these acres had, in fact, been offered to Reverend William King and the Elgin Association. The practical decision was made not to purchase them because most of it was low-lying marsh and they believed it would present an almost impossible challenge to make the land fit for agriculture. However, they underestimated the resolve of the black pioneers, used to surviving on very little and eager to have something more. A group of those hardy individuals moved into the marsh and dug ditches by hand to drain the surface water away. Soon, houses were erected in the drier clearings and crops were planted into what was becoming some of the richest soil in the township. Barns and fences were built to house and secure their pigs, chickens, and cows. Horses, rather than oxen, were the primary beasts of burden and means of transportation and every family hoped to have at least one in their stable.

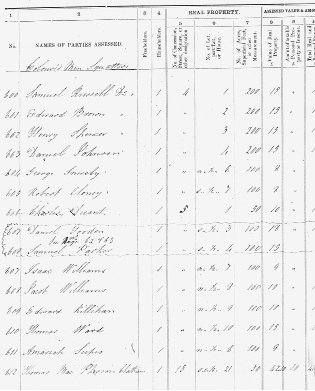

Samuel Russell joined the group of families who took possession of some of this land that no one else had any interest in at the time. The two-hundred-acre farm that the Russells selected was on the most westerly border of Raleigh Township in what had been surveyed and identified as Lot 1, Concession 4. When the tax collector made his annual trip throughout the township to assess each individual property, he scarcely knew what to do with this extended, all-black settlement of “squatters” that stretched up and down the area. He noted that Dr. Samuel Russell’s large farm was worth only fifteen pounds. By comparison, farms that were half that size on slightly higher ground within a few miles were worth ten times as much.[3] Because of the relative worthlessness of the land, Russell was only assessed one pence for his share of supporting the “lunatic asylum” and four pence for general school taxes. Added to that was one shilling, seven pence for Kent County taxes and four pence for Raleigh Township taxes. The assessor noted that Samuel Russell had “no goods” and assessed him a total of two shillings, four pence. Despite the fact that his taxes were relatively inexpensive — less than one day’s pay for a common labourer — Russell, along with several of his neighbours who were also squatters, was listed on the page of the tax assessor’s ledger with the heading: “List of the Uncollected Rates on the Collectors Rolls for the Township of Raleigh for the Year 1857.”[4]

Dr. Samuel Russell’s name appears at the head of the list of squatters in Raleigh Township in the 1857 Collectors Roll tax book.

Courtesy of Buxton National Historic Site & Museum.

To make matters worse for Russell and all of his neighbours, the government decided that they would finally offer the Raleigh Plains for sale and those who lived there would not necessarily get first chance to purchase. Opportunistic speculators — including Edwin Larwill — with questionable ethics and more political savvy, informed the commissioner of Crown Lands, who was stationed in Quebec, that the land was totally submerged and therefore not fit for agricultural purposes. Those who knew better insisted that “a large portion is as dry as the prairies of Illinois” and the rest could be drained with a lesser effort than would be required to clear the natural forest on nearby land.[5] Cutting the reeds and grasses that grew from six to nine feet high was certainly easier than cutting the elm, oak, or black ash trees that were so thick in adjoining parts of the township that children would often lose their way and vigilance committees had to be formed to rescue them.[6]

An Irish-Canadian farmer named Patrick Ryan had his eye on the lands claimed by Samuel Russell and accordingly wrote to the commissioner of Crown Lands to inquire if the lot was for sale, or if they had been legally claimed, and, if so, by whom. The reply stated that an official order-in-council signed by the attorney general had granted it to John McGregor more than half a century earlier, on July 5, 1796.[7] McGregor did not receive the original patent until May 17, 1802. The almost forgotten title was not completely cleared up until November 1859 when the late McGregor’s son and heir, Duncan, took undisputed title of the property when he received the deed from the county sheriff.[8]

Having now lost any hope of getting title to land on the Raleigh Plains, the Russell family now had to squarely face an even more painful reality — the potential loss of their Chatham home. John Fleming, who had sold them the house and held the mortgage, had become exasperated that Russell was not making his payments as had been promised. Even the first payment was then two years overdue and the scheduled final payment more than two months so. Unable to collect on his own, Fleming assigned the mortgage to a man named Henry Ruttle with instructions to “hereby authorize and empower the said Henry Ruttle his heirs or assigns to collect the same in my name by any legal or equitable process or otherwise that may be necessary …” To ensure that the transaction was legally documented, Fleming and Ruttle signed the Memorial of Assignment of Mortgage on January 11, 1858, and registered the document at the Kent Registry Office eight days later.[9] Interestingly, the value of the mortgage remained at 178 pounds, 15 shillings, which was the original purchase price.

Ruttle acted quickly and Samuel Russell had no choice but to put his mark to another document to “have assigned, transferred, set over, bargained, sold, revised, released, relinquished, and forever quit claim unto the said Henry Ruttle” any title to his home. For the sum of five shillings, a probably heartbroken Susannah surrendered any matrimonial claim and marked her X to the document that stated in part that she “hereby bars her Dower in the said Lands and relinquished the same.”[10]