Chapter Two

And We Became Desperate

We were thrust into the hold of the vessel in a state of nudity, the males being crammed on one side and the females on the other; the hold was so low that we were obliged to crouch; day and night were the same to us sleep being denied as from the confined position of our bodies, and we became desperate through suffering and fatigue ….[1]

— Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua,

Chatham, Canada West, 1845

The nightmare for the accused only became more vivid and painful as the minutes ticked by in the county jail. Hours turned into days until the entire month of November passed and December began. Despite his and his family’s protestations to the contrary and a total lack of evidence against him, Brown was not only imprisoned, but also tortured. On two different occasions, each within a week of the other, all of his clothing was removed, his hands and feet were bound together, and he was flogged with a cow-skin whip by the jailer, Sandy Buck. It was one hundred lashes to his naked body each time. Still, Brown denied the charges. To further add to his torment, Brown’s daughter, Lucinda, was arrested and placed into jail with her father. The vengeful authorities hoped that she could be induced to implicate him in the attempted murder. But she remained steadfast in her story that her father was entirely innocent and had been with her, three miles away, when the offence was committed. Her anguished mother, Susannah, made the same plea.[2]

Thirty-three days passed and still there was no evidence brought forward to substantiate the charges. In the absence of any legal foundation, Somerville decided to proceed with what was arguably the ultimate penalty — permanent separation of Brown from his family and banishment from the state of Maryland to the Deep South. Lucinda Brown heard that this sentence was carried out with the consent or advice of Governor Thomas G. Pratt.[3] At the time, the governor was wrestling in his own mind with the subject of proper punishment for slaves. By law, slaves convicted of serious crimes were not to be confined in the penitentiary, but could be whipped or sold out of state, whereas free persons of any race would be incarcerated for anywhere between two and twenty years. Pratt found this inconsistency appalling and felt that selling a slave into another state “would neither be considered by the slave or the community as any punishment whatever.”[4] Isaac, Susannah, Lucinda, and all of the Brown’s family and loved ones would disagree.

The widespread news of Brown’s case drew the attention of the Maryland slave traders who frequented the area jails, watching for deals to purchase runaways, blacks who were convicted of crimes, or for those who had been placed there “for safekeeping,” (which was often the code word for being held before they were sold South). Two such traders, Thomas Wilson and Samuel Y. Harris (a.k.a. Hickman Harris), visited the Prince Frederick jail to appraise the prisoner within. Both had ties to the largest of all the Maryland traders: Hope Hull Slatter, who headquartered his business in Baltimore and New Orleans. Wilson was in fact Slatter’s agent.[5] Harris, who lived in Upper Marlboro, had his own business and travelled the countryside looking for product to stock his own pen, promising to “take any number of negroes” and “give the highest market price in cash.”[6] Fudging slightly on the last point, Harris made the deal for Brown for $500 and in turn sold Brown to Hope Slatter for $665 — pocketing a quick and substantial profit in a few days’ time.[7]

The eighty-five-mile trip from Prince Frederick to Baltimore must have been excruciating for Brown. Pain came in many guises. The effects from the whippings and other terrors of his recent past were still fresh on his body and in his mind and would accompany him for a lifetime. Even more acute was the dread associated with the uncertainty for what the future might hold. Chances of ever seeing his family again were remote. Hope Hull Slatter was feared and hated by blacks across the country. Much had been spoken and written about him. He was raised in Georgia and, after borrowing $4,000 from his mother, moved to Baltimore and began his rapid rise to the top of the slave-trading ranks. Someone who knew him observed that although Slatter was very polite and took a special pride “on his good morals and genteel manners,” he was detested by most people in the city. Those facts were confirmed by Joseph Sturge, the founder of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. When the two men met, Sturge felt that Slatter was very courteous and was further gratified by the slave-trader’s assurances that he never parted families. Even more stunning was Slatter’s claim that his reputation for kindness among blacks was so admired that he was often asked by slaves if he would purchase them. He even left his slave pen in the care of a head slave for weeks at a time. Further suggesting his eligibility for sainthood, Slatter guaranteed his deeply devout Quaker guest that he had never swore “nor committed an immoral act in his life.” Clearly impressed, Sturge, in later correspondence, made the Freudian slip of spelling the slave trader’s name as Hope H. Slaughter.[8] Joshua Giddings, the United States congressman from Ohio, labelled Slatter as “a fiend in human shape.”[9] A more picturesque image, with no admiration intended, was given by the Underground Railroad martyr, Charles T. Torrey, who declared that “Slatter looks like Raphael’s picture of Judas Iscariot.”[10]

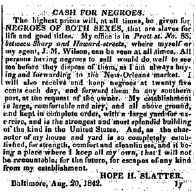

According to advertisements in the Baltimore Sun and elsewhere, including Sturge’s description, Slatter took pains to establish an impressive business. Many other newspapers from various states, as well as in England, carried the ad as a cautionary tale. The British Emancipator called it “the most shameful and horrible advertisements of those slave-dealers and traffickers in human flesh, who are making our country a hissing and by-word among the nations, and calling down upon us the vengeance of a just and holy God … Horrible! Most Horrible.”[11]

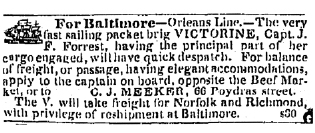

Hope Hull Slatter ran advertisements in several newspapers, including the Baltimore Sun for many years in the 1830s and 1840s. Abolitionist newspapers such as the Liberator (Boston) also frequently carried articles such as this one that appeared in its Friday, February 24, 1843, issue 8 edition, page 30.

Library of Congress Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room.

Isaac Brown and his fellow inmates, who shared the two-storey brick building with barred windows, would not have found the accommodations as opulent and comfortable as described. Appearances were important to Slatter and he allowed his stock to play cards or dance to fiddle or banjo music. Some visitors were treated to athletic exhibitions where the prisoners were taught to display “their power, their health, their ambition and their spirit, so they would be purchased in all confidence as contented, happy servants.” Slatter’s staff would roll up their sleeves to show their muscled arms. Occasionally, appreciative or sympathetic onlookers would throw pennies to them through the tall stockade gate. There was an enclosed courtyard, approximately twenty-five square feet, where the inmates where allowed to spend the daylight hours. However, all was not as benign as appeared on the surface. The brick walls surrounding the yard were about twenty feet high, and a large and ferocious bloodhound helped to serve as a sentry. One who had spent time within those walls had the duty of preparing other slaves for sale by greasing their bodies as to enhance the appearance of their physiques. Both male and females were often stripped naked and tied face-down on a bench and held down by two or four men and strapped with a leather strap rather than a cowhide whip so as not to cut into the flesh.[12]

Isaac Brown’s stay within the pen was short-lived as a shipment of slaves was due to depart within days of his arrival. A northern newspaper reported first-hand observations of a group of slaves who were removed from Slatter’s pen and loaded onto a train car, soon to be loaded onto a ship destined for the Deep South:

About half of them were females, a few of whom had but a slight tinge of African blood in their veins, and were finely formed and beautiful. The men were ironed together, and the whole group looked sad and dejected.… In the middle of the car stood the notorious slave-dealer of Baltimore, Slatter.… He had purchased the men and women around him and was taking his departure … this old, grey-headed villain, — this dealer in the bodies and souls of men …

Some of the colored people … were weeping most bitterly. Wives were there to take leave of their husbands, and husbands of their wives, children of their parents, brothers and sisters shaking hands perhaps for the last time, friends parting with friends, and the tenderest ties of humanity sundered at the single bid of the inhuman slave-broker before them.[13]

It is not recorded if Isaac Brown had a similar heart-wrenching parting with his loved ones, who remained at his former home in Calvert County, many miles away. Perhaps their goodbyes were exchanged at the Prince Frederick jail. To help ensure that he remained in control, Slatter generally loaded his human cargo onto a train of omnibuses and followed the procession to the wharf on horseback, “callous to the wailings” about him.[14] We are left to wonder if the two traders who had first inspected Isaac Brown in the Prince Frederick jail, Thomas Wilson and Samuel Harris, were Slatter’s agents at that scene who were described as “two ruffianly-looking personages, with large canes in their hands, and, if their countenances were an index of their hearts, they were the very impersonation of hardened villany itself.” One of these men, who knocked a husband down as he tried to say farewell to his wife, was further described as “a monster more hideous, hardened and savage, than the blackest spirit of the pit.”[15]

Slaves bound for southern destinations from Hope Hull Slater’s pen in Baltimore were transported under cover of darkness to awaiting ships by a horse-drawn omnibus, such as the one pictured above. In Five Hundred Thousand Strokes for Freedom: A Series of Anti-Slavery Tracts, Wilson Armistead reprinted the observations of an unidentified British traveller that had originally been printed in the Leeds Anti-slavery Series, No. 9, which related a touching scene: “I saw a young man who kept pace with the carriages, that he might catch one more glimpse of a dear friend, before she was torn forever from his sight. As she saw him, she burst into a flood of tears, and was hurried out of his sight, sorrowing most of all that they should see each others’ faces no more.”

Courtesy of Maryland Historical Society Special Collections, Image ID: Z.24.65 VF.

On December 17, 1845, Isaac Brown was placed on board the two-masted ship Victorine at Wilson’s wharf at the Baltimore Harbor along with eighty-two others. The Victorine regularly made the circuit from New Orleans to Baltimore with occasional stops to load or unload shipments at Norfolk and Richmond, Virginia, or Charleston, South Carolina, and at more northerly ports such as New York City. The vessel was described as being “the very fast sailing packet brig … having elegant accommodations.”[16] What the advertisement did not make clear was that those “elegant accommodations” were reserved for the very few paying southbound passengers who were comfortable enough to book passage on a domestic slaver. Travellers from New Orleans to more northerly ports were more likely to purchase a ticket knowing that the cargo consisted of such inanimate goods as bags of corn or wheat, bales of cotton and hemp, and barrels of pork, lard, and molasses.

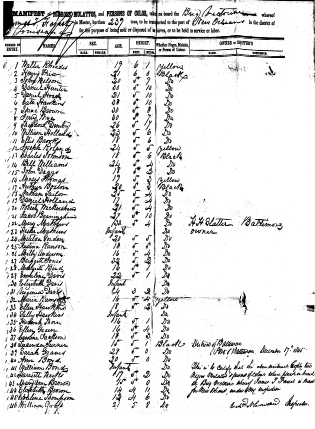

Brown and his fellow sufferers replaced that merchandise in the hold for the coastal voyage.[17] Joining them were fifteen other slaves belonging to other area dealers, Joseph Donovan and Bernard Campbell.[18] While the slaves were trying to grasp the reality of what was about to befall them, Hope Slatter signed the necessary documents with the port authority. He provided a list of all of the names, ages, and heights. They were further described by their colour: black, brown, or yellow. Most of the thirty-nine men were in their twenties. There were eighteen people in their teens and twenty aged twelve and under — twelve of whom were listed as “infants.” There were forty-three females, many of them mother and child. It is particularly poignant to read the names of the many members of the Haley family — fifteen in all whose ages ranged from thirty-eight for Larry to two years for John. We are left to wonder what the circumstances were for all of them to be sold. At least in this case, Slatter appeared to be true to his word not to separate families. But what New Orleans buyer would have either the financial means or the inclination to make such a large purchase to keep them together?

Isaac Brown was listed as black, five feet eight inches tall, and thirty years old. Slatter fudged Brown’s age by many years as he was actually in his mid-forties, and, except for one person listed as fifty-one, older than everyone else in the shipment. This was probably the early stages of his plan to make Brown more attractive to prospective buyers. The still unhealed stripes across his back would make most shoppers shy away from expressing any interest as it was believed that slaves who had evidence of whippings were headstrong, unmanageable, and bound to be more trouble than they were worth. Volunteering his true age would only compound the challenge. To reinforce the illusion of youth, a common tactic in the trade was to meticulously pull out any grey hairs, or, if there was too much, dye it all.[19]

The image shown is an Inward Slave manifest to port of New Orleans. Isaac Brown appears as no. 7 on the list. Note that there are two young women with the surname Brown — no. 43 and no. 44 — Mary Ann, age fifteen; and Elizabeth, age fourteen. There is no evidence to suggest that they may have been related to Isaac. These manifests are also available online from www.ancestry.com.

National Archives Records Administration, Washington, D.C., Record Group 36, U.S. Customs Service Records, Port of New Orleans, Louisiana, Inward Slave Manifests 1846, microfilm roll 16, 1846–47, image 19.

Before the Victorine could be cleared to disembark, both Slatter and the ship’s captain had to sign the manifest for Richard Snowden, the inspector of the customs house, to swear that the dealings were legal and did not contravene the United States abolition of the transatlantic slave trade that had taken place thirty-seven years earlier. At 10:00 o’clock, the principals put their signatures to the document:

District of Baltimore, — Port of Baltimore,

Hope H. Slatter owner & shipper of the persons named, and particularly describe in the above manifest of slaves and James T. Forrest, Master of the Brig Victorine do solemnly, sincerely, and truly swear, each of us to the best of our knowledge and belief that the above slaves have not been imported into the United States since the first day of January, one thousand eight hundred and eight; and that under the Laws of the State of Maryland are held to service or labor as slaves and are not entitled to freedom under these.

Sworn to this 17th day of December 1845.

Hope H. Slatter

James T. Forrest[20]

The weather had been particularly harsh as the Victorine attempted to leave the harbour. The steamer Relief, a specially designed “ice boat” that was employed to cut through the frozen ice of the Chesapeake Bay, towed them out to open water.[21] There had been gale-force winds the previous day and heavy snows surrounded them, most particularly to the south. The knowledge that ships had been battered and damaged in the storms and heavy seas of that week added to the feelings of dread and the confinement, and the crowding and the discomfort did nothing to help the cargo find their sea legs. As they sailed into an unknown future and into the Christmas season, those hanging precariously to their faith must have questioned how God could have so unmercifully forsaken them. Although probably locked away in the cargo hold to prevent escape, Isaac Brown would have gazed with his mind’s eye upon the familiar coast of Calvert County and the faces of his loved ones as the ship passed by his home. He had no way of knowing that his former master, Alexander Somerville, who was recovering from his wounds, had confided to Susannah Brown that upon reflection he no longer believed that Isaac had shot him and regretted having sold her husband whom he always considered to be “a peaceable and quiet man, and had done everything he wanted him to do.”[22]