Chapter Four

By the Law of Almighty God

By the law of Almighty God, I was born free — by the law of man a slave.[1]

— Aaron Siddles, Chatham, 1855

During the summer of 1846, a quiet stranger calling himself “Samuel Russell” departed from Pittsburgh in the free northern state of Pennsylvania and took up residence in Philadelphia. He was stout in stature and appeared to be in his mid-forties. He was guarded about revealing personal details of his past life. It was not uncommon for runaway slaves to lose themselves in that city, which had a large black population and a citizenry with a reputation for possessing strong anti-slavery sentiments. Numerous benevolent societies as well as a public Alms House that also housed an Infirmary existed to render aid to the poor and the sick. There were eighteen black churches — Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Methodist, and Baptist — scattered across the city to tend to the spiritual needs of the twenty thousand coloured inhabitants. Several schools, libraries, and literary societies had been established to encourage education and the expansion of the mind. Opportunities existed for employment and for becoming property owners for the able-bodied and the industrious, and for those who summoned the strength to overcome their private adversities that possessed a sinister way of removing all hope.[2]

But those aspirations and accomplishments were not automatic for those who, like Samuel Russell, arrived penniless. He moved into one of the poorest districts, which was already over-crowded with recent immigrants. It was common for some of these recent arrivals to sleep outdoors when conditions allowed, and to huddle together in larger groups in shanties when the weather turned against them. The winter of 1846–47 was particularly punishing for them, with freezing temperatures and an epidemic of yellow fever (also known as typhus). Malnutrition and exposure worked in tandem with the fever to send dozens to their graves. Many frozen bodies were found in backyards and alleys or in crude shelters with bare wooden or earthen floors, and with crevices in the walls that allowed the winds to whistle in. Some were asphyxiated from the smoke while huddling around a small coal fire in a stove without a chimney pipe. Many of these were released from a life of begging, stealing, gathering scraps of food discarded from other people’s kitchens, or from their miserable occupation collecting and selling rags and bones.[3]

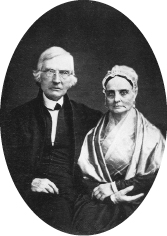

Samuel Russell survived the winter — and whatever hardships he may have experienced in his past. It was hard to guess his status, free man or runaway slave. But he was obviously lonely, despite having developed many friendships in the area. His recent experiences proved to him that some people could be trusted, so he confided his secrets to members of the anti-slavery community, among whom were James and Lucretia Mott, a soft-hearted and quiet Quaker couple who were leaders in that society. James Mott offered Russell a job in his store at 35 Church Alley, which specialized in selling “free produce” dry goods, including cloth made from cotton that had not been picked by slaves. Among the items that they handled were: “Manchester Ginghams,” “Canton Flannel,” Bird Eye Towels,” “black and white Wadding,” and “Calicoes,” as well as aprons, furniture, lamp wicks, bed ticking, and stockings.[4]

Reuniting the family was viewed as even more important than providing an income for “Russell.” Members of the anti-slavery society clandestinely arranged to deliver his wife and nine of their children from Maryland to Philadelphia so they could be with their husband and father. The joy of that meeting can only be imagined. But with two more of their grown-up children remaining in Maryland, there were still vacant spaces in the family circle.

Seeking to fill those empty spaces, Russell took up his pen to compose a letter to his eldest son, addressing it to Calvert County, Maryland. He wrote his return address — 172 Pine Street, between Fifth and Sixth — and asked the intended recipient of the letter to direct their reply to that address. Before taking the letter to be posted, he made the ill-advised but unavoidable mistake of signing his real name “Isaac Brown.”

Trains carried the mails daily from Philadelphia to Baltimore where letters and packages were distributed to the rural postmasters by horseback or coach.[5] Maryland postmasters were instructed to beware of mail that might have “a tendency to create discontent among and stir up to insurrection, the people of color of this State.”[6] While Brown’s letter, which was written to reveal his whereabouts to his son and beseech him to join the rest of the family, would not have strictly fallen under those guidelines aimed at abolitionist literature, it was still risky to reveal his true identity. The owners of any prying eyes who had knowledge of Hope Slatter’s attempts to retrieve Brown stood to be handsomely rewarded for supplying information as to his whereabouts. Knowing that runaways would try to get in touch with loved ones made any mail that the younger Browns might receive the subject of close scrutiny.[7]

Somehow the contents of the letter became known to Alexander Somerville. No doubt enraged that he had already lost the services of Susannah Brown and her children who, although free, worked on his farm, Somerville shared the information contained in the letter with Slatter. Determined to recover the $665 purchase price plus the considerable expense he had incurred in housing and shipping Brown in Maryland and Louisiana, Slatter and Somerville concocted a plan so audacious that it would include the involvement of the highest office in the state.[8] Somerville signed a sworn affidavit charging Isaac Brown “with the crime of assault with intent to kill him.” The sympathetic Governor Thomas G. Pratt, himself a slave owner, who had recently suffered the indignity of having one of his own slave women escape, acted upon his word.[9]

Governor Thomas Pratt of Maryland sent an official request to the governor of Pennsylvania to have Isaac Brown extradited to answer to the charge of “assault with attempt to kill” Alexander Somerville.

Courtesy of Pennsylvania State Archives and Karen James, Pennsylvania State Archives, RG-26 Extradition files, Papers of the Governors.

On April 26, 1847, Governor Pratt issued a requisition to Governor Francis R. Shunk of Pennsylvania, requesting the arrest of Brown on an attempted murder charge and delivery of him to the official Maryland agent, John Zell.[10] According to the United States Constitution, “a person charged in any State, with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee from justice, and be found in another State, shall on demand of the Executive authority of the State from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the State having jurisdiction of his crime.” Accepting the requisition at face value as he was legally compelled to do, Shunk acted quickly and the next day issued an order to Judge Anson V. Parsons “or any other Judge or Justice of the Peace in this Commonwealth” to issue a warrant to any officer of Philadelphia to apprehend, secure, and deliver Brown to Zell. The governor’s order never reached the hands of Judge Parsons, but instead was received by John Swift, the mayor of Philadelphia, who issued the arrest warrant. A few days passed, allowing time for Zell to travel from Baltimore to Philadelphia to meet with local constables and for the legal processes to be put into motion. On Sunday, May 2, armed with a warrant from the mayor, Zell, along with Philadelphia officers William Young and Daniel Bunting, appeared at the Pine Street home and took the stunned Brown into detention and placed him overnight in the northeast police station house on Cherry Street until he could be conveyed to Maryland the next day to — supposedly — stand trial on the charges.[11]

Word of Brown’s arrest quickly spread throughout the black community and a large group assembled to express their outrage. They quickly saw through the ruse that Brown was going to be extradited for trial on the charge of attempted murder, knowing that in fact he was only going to be re-enslaved. Communication was made to influential friends who were members of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. They quickly set up an Acting Committee to devote themselves to Brown’s case.[12] Before the day was over, a group besieged Judge Parsons, telling him of the injustice, and asked him to intervene. Unaware of the governor’s or the mayor’s involvement, and thinking the request reasonable, Parsons issued a writ of habeas corpus, the official Latin term for the order of a judge to a prison official ordering that an inmate be brought to the court so it can be determined whether or not that person is imprisoned lawfully and whether or not he should be released from custody. Habeas corpus is described as the fundamental instrument for safeguarding individual freedom against arbitrary and lawless state action. Parsons directed this writ to John Zell, who was considered to have possession of Isaac Brown, and directed them both to appear before him the next day.

The next morning, on May 3, lawyers, members of the abolition society, female members of the Society of Friends (commonly known as “Quakers”) and a large black delegation filled the first floor court room at Congress Hall to witness the official hearing at the Court of Common Pleas with Judge Parsons, along with Senior Judge Edward King presiding.[13] The future proceedings continued to draw large numbers of supporters with the courtroom packed, the outer halls full, and the overflow crowd milling about outside. The building had a special significance to the American people, having been the location of the second inauguration of President George Washington and the home of Congress for the decade when Philadelphia was the capital of the newly formed United States. At that time the Senate met on the upper floor and the House of Representatives on the main floor below.

Thomas Earle served as legal counsel on several other anti-slavery cases. In 1840, he unsuccessfully attempted to wield more political clout for his causes by running for vice-president of United States in 1840 on the Liberty ticket with James G. Birney.

Courtesy of Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania.

The courtroom itself was designed to inspire decorum and obedience, with the judges perched behind an elongated desk on an elevated platform, high above those in attendance. The recording clerk sat at a small desk, immediately below the judges. Slightly forward to both the left and the right were tables and chairs for the lawyers. Benches for jurors ascended at right angles on either side like small choir lofts in a church. The crowd was separated from the principals by a wooden railing that ran the width of the room. The shackled Isaac Brown stood at centre focus within a waist-high iron-barred prisoner enclosure, dwarfed and intimidated by those who held his future in their hands.

Abolitionist lawyers Thomas Earle, Edward Hopper, Charles Gibbons, and, later, David Paul Brown, stood for the defence — a stance recorded by a fellow lawyer as whose “championship of so desperate and so unpopular a cause demanded physical, no less than moral courage on the part of its advocates. The bar as a body, conservatively gave it the cold shoulder, and Mr. Hopper and his associates were, in truth, the victims, frequently of positively uncivil treatment at the hands of their brother lawyers.”[14]

The defence team, who appeared immune to any societal pressures, were particularly imposing. Charles Gibbons, whose father had been an active member of a society founded to protect free blacks from kidnapping and had saved or rescued many slaves from the Baltimore slave markets, was the speaker of the Senate; the soft-spoken but brilliantly articulate Thomas Earle was a former United States vice-presidential candidate for the Liberty Party; Edward Hopper, the son of anti-slavery giant Isaac T. Hopper, who always dressed in the grey conservative Quaker attire, was a witty and amiable personality and had a very large practice; David Paul Brown was renowned for his powers of persuading jurors with his oratorical skills and courtroom theatrics replete with a prominently displayed gold snuff box, elaborate clothing, conspicuous jewellery, and “dandified manners.”[15] In this case, the lawyers took aim at the particular issue of the charge that Isaac Brown had “fled from the justice of that State.” They were prepared to persuasively argue that this could not possibly be the right man as Brown had never voluntarily fled from Maryland.

Gibbons spoke first, vehemently calling the charge a “gross fraud and an imposition upon the Governor” with the only intention being to return an “alleged” fugitive slave to bondage. Clearly taken by surprise at the scope of the argument and the upper level of government involvement, Judge Parsons told the court that he was not even aware of Governor Shunk’s warrant or he would never have issued the writ of habeas corpus and would have simply issued a warrant to deliver Isaac Brown into John Zell’s custody. The judge announced that legally he could only address the issue of establishing that Brown was indeed the person named in the warrant.

This scene, with Independence Hall in the centre and Congress Hall the smaller building to its right, was the location for Isaac Brown’s legal hearings in Philadelphia. Published in 1875 by Thomas Hunter.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. LC-DIG-pga-03855.

Zell protested that this was indeed the proper Isaac Brown who had betrayed his own whereabouts in the intercepted letter that he had sent to Calvert County. Ignoring the argument, Gibbons attempted to buy time by telling the judge that an emissary had been sent to the governor to lay the true facts before him rather than the faulty information that he had formerly received. The perplexed judge, not wishing to appear to question the judgement of his superior, expressed that he had to presume that Governor Shunk would not have acted until he was confident that he was fully informed and that the case was strong. Judge King concurred, stating that it was his duty to carry out the views of the governor.

Gibbons would not back down and mentioned several precedents and points of law to back up his argument. Finally, Judges Parsons and King agreed to take a recess to await the response of the governor and to allow time for Zell to produce evidence as to the identity of the accused. Pennsylvania newspapers shared the touching scene of wife Susannah and his children, who had at some time arrived in Philadelphia, weeping outside the courtroom as Isaac Brown was retained in custody without opportunity of bail and placed in the Moyamensing Prison. Across the state line, the Baltimore Sun copied the same article verbatim — with the exception of the image of Brown’s heartbroken family — in its columns.[16]

When court resumed at 4:00 p.m. the following afternoon, the Maryland delegation was well-prepared. They now had a powerful lawyer, Edward Duffield Ingraham, who, despite being from Pennsylvania, devoted some of his career ruling on returning fugitive slaves from Philadelphia to Southern states.[17] Perhaps his sympathies were influenced by having married a woman from Maryland.[18]

In order to respond to Judge Parsons’s demand of the previous day, the Maryland prosecutors had brought in two different men — both slave traders who should know — to positively identify Brown. One was Hope Slatter’s agent, Thomas C. Wilson, who had often seen Brown in the Baltimore slave pen in 1845. The other was Samuel Y. Harris, who had purchased Brown from Somerville and then quickly resold him to Slatter. Harris had travelled 185 miles to Philadelphia, supposedly just to confirm the identification. It took little imagination to realize that these men were expecting to be handsomely reimbursed for their travel by being given the reward of being able to resell Isaac Brown yet again.

During the course of cross-examination, Charles Gibbons pointedly asked Wilson what would appear to be the definitive question that would unequivocally settle the case: “Did not Mr. Slatter send Isaac Brown to Louisiana, and was he not sold in that State?” Mr. Ingraham objected to the question and the judge inexplicably agreed and ruled in his favour. The query was left unanswered.

A short testimony by Samuel Y. Harris followed, confirming that he recognized Isaac Brown from having seen him in the Prince Frederick jail where he was held on suspicion of having shot Alexander Somerville. Evasive and dishonest with the facts, Harris stated that he believed Brown was in jail for only two days “before they took him to Schlatters yard in Baltimore” and he had never seen Brown again until this day. Harris made no mention of having purchased or sold him. Ingraham coolly rested his case asserting that the prisoner’s identity had been clearly established and requested that Brown be surrendered to the agent from Maryland.[19]

It was then Charles Gibbons’s turn to voice his objections. He passionately claimed to have the right to bring all of the facts of the case into the light. He again stated what everyone in the courtroom already knew — that the case was simply a vicious trick to attempt the legal kidnapping of Brown and that the governor had not been presented with the truth. A hesitant Judge Parsons agreed to let the arguments be made and the case played out.[20] Allowing the animated Gibbons to catch his breath, his impressive and dignified partner, the tall, always elegantly dressed Thomas Earle went on the offensive. Earle continued at length, questioning in lawyer jargon the fine legal philosophy as to whether the governor was acting as an officer of Pennsylvania or of the entire United States, until, to the relief of many in attendance, court was mercifully adjourned for the day.

The legal manoeuvring continued, both in the forefront and behind the scenes. Charles Gibbons dispatched an emissary, William Christopher List, who had been present in the court to the state capital in Harrisburg to speak directly to the governor. Gibbons also sent a letter to inform the governor that he had never seen such a widespread and pervasive feeling of sympathy for anyone accused and confided that Judge Parsons did not seem inclined to question the elected head of state’s authority. After quoting points of law, Gibbons beseeched the governor to, at the very least, request that the case be closely examined. Appealing to His Excellency’s emotions and humanity, Gibbons closed with the request “to give the prisoner his liberty — joy to his wife & large family and defeat this attempted fraud upon the act of assembly”[21]

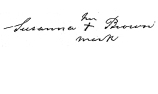

Co-counsel Thomas Earle also wrote to the governor, enclosing affidavits that proved that Brown had never fled from Maryland. Earle shared his findings about Somerville’s shooting and that, although it was illegal in that state for a black to give testimony against a white person, they were allowed to testify for one of their own race. Although there was no one of any colour who could testify as to Brown’s guilt, there were several blacks who were willing to assert that he was innocent of the charges, but none were allowed to speak. Instead, the legal case was abandoned — according to sources, with the knowledge and consent of Governor Pratt.[22] To bolster and humanize the correspondence, Earle included the sworn affidavits of Susannah and Lucinda Brown, which gave their version of the past events. Unable to write, mother and daughter signed their names the only way they knew how — with an X.[23]

Unable to write, mother and daughter signed their names the only way they knew how.

Members of the general public, such as James Mott, the respected Quaker and spouse of the more famous abolitionist and women’s rights advocate Lucretia Mott, sent similar appeals.[24] Their collective entreaties had the intended effect, as Governor Shunk sent a request to Judge Parsons to suspend further hearings until he could evaluate the case. To assist in this, the governor sought the advice of Benjamin Champneys, the attorney general for Pennsylvania, in interpreting the 1793 Act of Congress that concerned the apprehension and delivery of fugitive slaves. Only a few days earlier, Champneys had written a long and well-considered opinion advising Governor Shunk to refuse to extradite three other runaways to Maryland. In that case, the request had strictly been that the slaves owed their service and labour to their master and had committed a felony under Maryland law by running away. Shunk and Champneys agreed that what may have been a felony in Maryland was no crime in the free state of Pennsylvania. The apologetic tone of Shunk’s letter would have done nothing to assuage his counterpart: “I sincerely regret that a difference should exist between the authorities of the State of Maryland with Pennsylvania, in regard to the construction of our common bond of union, I am constrained, respectfully, to decline issuing warrants for the arrest and delivery of the persons named in your said requisitions.”[25]

On the surface, Isaac Brown’s case was different, inasmuch as he was charged with being a fugitive from justice cited for assault and battery with intent to kill. But the difference was only superficial, with the ultimate intention of returning the accused to slavery being the same. Pennsylvania’s stance related to Brown was intended to be a landmark decision, establishing once and for all the issue of conduct in dealing with requisitions to return fugitives to another state. Champneys travelled the eighty miles from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, to attend the Philadelphia court in person and to voice his own request on behalf of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania that the case be arrested until he could fully investigate it. The appeal was so granted, and the gut-wrenching case ground to a halt pending the attorney general’s ruling.[26]

James and Lucretia Mott were activists and leaders in the anti-slavery movement for much of their married lives. Isaac Brown was just one of legions of former slaves whom they assisted. In addition to their work, which included raising a large family, the couple travelled extensively to address the social and spiritual issues that they believed in. Lucretia was almost assuredly the “venerable Quaker lady” described on May 15, 1847, in Rhode Island’s Newport Mercury, who sat with the weeping Susannah Brown and four of her children in a carriage in front of Independence Hall nervously watching the mob that had assembled to protest the arrest of Isaac Brown.

In a cruel irony of timing, the black population of Philadelphia had chosen that day to publicly celebrate the recent passage of a Pennsylvania anti-kidnapping law by the state legislature with programs and demonstrations of thanksgiving at area churches and elsewhere.[27] The law, which was advocated by the anti-slavery society and passed by a general assembly of the Senate and the House of Representatives, stated that it was henceforth a criminal offence to carry away or cause to be carried away anyone, or by fraud or false pretence take any free black for the purpose of being sold. Any participants in such a plan would be sentenced to hard labour and solitary confinement for a period no less than five years or more than twelve years. They would also be fined a minimum of $500 and maximum of $2,000 with the amount split between the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the person who brought forward the prosecution.[28] For the state’s African-American community, who were used to having their rights short-changed, the celebrations were now somewhat tempered as they kept close watch on how — and if — the law would be implemented.

In the interim, Isaac Brown languished in jail, nervously awaiting his fate. As would be expected, despite the grandiose exterior that resembled a gothic-styled medieval castle hewn from polished white granite, conditions in Moyamensing Prison were uncomfortable, with 464 prisoners held within, including fifty-eight blacks. Crimes ranged from serious felonies to misdemeanours such as vagrancy.

By the time this photograph was taken in 1896, the bright marble exterior of Moyamensing Prison had faded in the half century since Isaac Brown had been imprisoned there. The prison was used from 1835 to 1963. Edgar Allen Poe and Al Capone were among the distinguished inmates.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62 -63344.

A philanthropic group, known as the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, frequently visited to provide moral and spiritual support as well as to make recommendations to ensure that conditions were acceptable. They filed regular reports to record their observations. In one they noted that three tiers of cells were on either side of the extensive corridors and the entire building was lit and ventilated from the roof. One cell block, presumably where Isaac Brown was housed, was reserved for prisoners who had not yet been sentenced. The nine-by-eleven-feet-wide cells had arched ceilings and were said to be well-furnished with each having running water delivered in pipes. The entire building was heated by a long flue that ran under the floor of the first storey. There was a library with a small selection of books available to prisoners. Although it was recorded that the food was well-prepared and available in sufficient quantities, some inmates complained of the lack of variety. Judging by the recent deaths of four black prisoners, caused by inadequate food and ventilation, the report had its flaws.[29]

During the lull in the proceedings, much of the Philadelphia public diverted their attention to the arrival of the miniature “General” Tom Thumb, who was fresh from a triumphant tour of Europe where he was reported to have met with several of the Crown heads, including Queen Victoria, who showered him with expensive gifts. At least one newspaper reported that his receipts from the tour were the equivalent of $750,000. The wag who wrote the article calculated that amount in silver would weigh twenty-three tons and that it would take fifty-five horses to haul the precious cargo.[30] The sixteen-year-old, fifteen-pound, twenty-seven-inch-tall Tom performed three shows a day at the city museum along with his “pigmy ponies, chariot and elfin coachman and footman” who wore cocked hats and wigs. Tom delighted his audiences with impersonations of Napoleon, a highland chief, Frederick the Great, and ancient Romans and Greeks. The mayor hosted him in his home and the female “beauties” and “elites” flocked around the diminutive charmer. He claimed to have been currently engaged to eight different women, which he modestly claimed to be enough for any one person.[31]

But despite whatever events were happening around the city, focus remained upon the Brown case. The black population of Philadelphia was becoming increasingly agitated. The editor of the Pennsylvania Freeman tried to incite its readers into a frenzy of indignation over the trampling of the rights of one of the God’s creatures. The principal penny newspapers of Philadelphia, the Sun and Spirit of the Times, did likewise by publishing details of Brown’s brother’s brutal death at the hands of Somerville and the lack of any evidence of Brown being the one who had shot Somerville. The newspapers also relayed the injustice of the imprisonment of the innocent daughter Lucinda Brown for several days and her father’s forced exile away from his wife and twelve children (contrary to the eleven children recorded elsewhere) when he was sold to Slatter and then to the Deep South. The Freeman went even further by publicly challenging Judge Parsons to have the courage to stand up for right “though his decision shall put all Baltimore, aye! all Maryland in a blaze.”[32] The flavour of the reports in the Maryland newspapers differed a great deal, informing their readers of the injustices they were being subjected to.[33]

The Maryland contingent, not wanting to delay by awaiting the ruling of Pennsylvania Attorney General Benjamin Champneys, attempted to make pre-emptive measures. A grand jury in Calvert County was hurriedly organized, which formally indicted Isaac Brown. The jurors had apparently already decided Brown’s guilt ruling that he:

[W]ith force and arms at the County aforesaid in and upon the said Alexander Somerville in the peace of God and the State of Maryland then and there causing did make an assault with an intent … then and there feloniously wilfully and of his malice aforethought to Kill and Murder and other wrongs to the said Alexander then and there did to the great Damage of the said Alexander against the act of Assembly in such case made and provided and against the peace government and dignity of the State.

The document continued at considerable length with similar wording so as to leave no doubt of the Grand Jury’s stance.[34]

Thomas George Pratt completed his term as governor of Maryland in January 1848. His political retirement was short-term as the General Assembly elected him to the United States Senate. During the Civil War, the Northern forces were suspicious of him because of his pro-slavery views and confined him for several weeks.

Library of Congress Prints and Photograph Division, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-cwpbh-00201.

Armed with this, on May 11, Governor Pratt again presented a requisition to Pennsylvania’s governor with all of the formal requirements of the law addressed. When it arrived the next day, Attorney General Champneys was just finishing writing his opinion, which incidentally found that the earlier requisition was not sufficient to hold Brown in custody. However, in consequence of the secretary of state advising Champneys of the new requisition, his work was outdated and was set aside.[35] Shunk revoked the previous warrant and instructed Judge Parsons that a new one had been issued.[36] Parsons received the letter on Friday, May 21, and prepared for court on Monday morning, at which time he would release Isaac Brown to the agents from Maryland. The next day’s edition of the Public Ledger informed its readers of the latest development. The attorney general and the governor had reviewed the law and made their ruling. It appeared that all legal avenues were closed and Judge Parson’s direction was clear.

Feeling that all was now lost, the news sent a wave of terror, desperation, and heartbreak over Brown and his allies.