Chapter Six

One More River to Cross

O, Jordan bank was a great old bank,

Dere ain’t but one more river to cross.

We have some valiant soldier here,

Dere ain’t but one more river to cross

O, Jordan stream will never run dry,

Dere ain’t but one more river to cross

Dere’s a hill on my leff, and he catch on my right,

Dere ain’t but one more river to cross.[1]

— From Army Life in a Black Regiment

The Brown home at 172 Pine Street had been completely vacated. Susannah and her children would take no chance that the location of their husband and father could never again be traced through them. The family had already been separated for extended times and they had endured the anguish of the recent legal proceedings. The return of runaway slaves was handled differently in the many jurisdictions in the many northern states and there was no certainty that Isaac Brown would be safe in any of them. The widespread coverage of his story and its final disposition in Pennsylvania invited Alexander Somerville, Hope Slatter, the governor of Maryland, and others to make further attempts to recapture him. Flight to Canada appeared to be the best — perhaps the only — option. But getting a family of two adults and nine children there without attracting undue notice was quite a different matter. Depending upon their route, the journey would be six hundred miles, maybe more. They would have no other option than to take very public means of transportation — trains cross-country and a boat across the Great Lakes. Bounty hunters, doubly inspired by recent events, might be lurking at every station and port along the way to recapture the now famous fugitive. A period of hiding out until the high-profile case began to fade somewhat from the fore of the public consciousness seemed the prudent course of action.

One thing was certain, Pennsylvania was not safe. Luckily, the anti-slavery societies such as the branch in Philadelphia and Underground Railroad operatives that were liberally sprinkled throughout the northern states were well-connected and in regular communication with one another. Two major assemblies had taken place in the month that Isaac Brown had been in custody: the annual meeting of the American Anti-slavery Society that began on May 11 in New York and the New England Anti-Slavery Convention that took place in Boston on May 25. The remarkable and well-publicized proceedings in the Philadelphia case would certainly have been a prominent subject for conversation, particularly in Boston, coming as it did so soon after Brown’s release.

Some of the attendees, such as James and Lucretia Mott, would have been especially familiar with the intimate details. The long-standing and exceptionally well-respected Quaker couple were on warm terms with the officers of the convention: president Francis Jackson and secretary Edmund Quincy, both of whom also held those same positions with the board of managers of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. William Lloyd Garrison, the most prominent national abolitionist leader, who served as president of the American Anti-slavery Society and editor of the most influential anti-slavery newspaper, the Liberator, was also in attendance, as was Frederick Douglass, the most prominent black leader of the era.[2] An unnamed “fugitive slave from Louisiana” in the audience was also introduced to address the crowd. At first he could not find the words to speak, but after giving way on the podium to another fugitive who spoke of his escape, he became emboldened enough to tell the crowd that he “wished the hall was five million times bigger than it was and that his voice was like six million thunders to fill it.”[3]

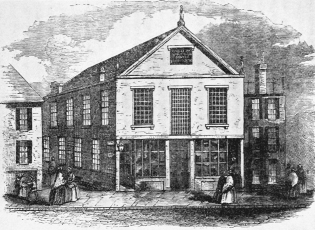

This African-American Church in Boston is identified as the Twelfth Baptist Church with its congregation dating from 1840. Leonard A. Grimes, who became pastor there in 1848, was active in the Underground Railroad. In 1887, William J. Simmons, author of Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, wrote on page 664: “hundred of escaping slaves passed through his hand en route to Canada.” Several other notable black figures, including Lewis and Harriet Hayden, Shadrach Minkins, Anthony Burns, and Thomas Sims, were members.

Courtesy of Milstein Division of United States History, Local History & Genealogy, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, Image ID: 1228854.

Although the identity of this fugitive from Louisiana is uncertain and other details are of necessity shrouded in secrecy, it is clear that Isaac Brown — who once again became “Samuel Russell” — along with his family, was quietly whisked away to New York City, which had its own sophisticated anti-slavery community.[4] It was there that he met with executive members of the American Missionary Association.[5] Arrangements were made that the Brown family was to be taken under the wing of Reverend Samuel Young, a forty-one-year-old Congregationalist minister from nearby Williamsburg, Long Island, who was also a friend of the Hopper family, who were so personally involved in the Brown case.

A view of Boston near the time that the Browns arrived there. Published by N. Currier, circa 1848.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-5249

Reverend Young had an interesting and occasionally melancholy history of his own. Born in New Jersey to a poor family, he was abandoned and sent out into the world as an orphan. He could never recall having seen his parents’ faces or heard their voices. Surviving the many trials of his youth, he came to embrace Christianity and became a dedicated minister. He was never able to overcome poverty in his lifetime, but had no desire to do so. Married with eight children of his own, Young was uniquely capable of empathizing with the individual members of the Brown family.[6]

For over a month, from late May until mid-July, the Browns were hidden away in New York, then in Boston, where they fell under the protection of Francis Jackson, Edmund Quincy, and William Lloyd Garrison. It was not until then that those involved acquired a wavering confidence that it was safe for the family to attempt the trip to Canada, long a favoured destination for fugitive slaves. The Dawn Settlement, near the village of Dresden in southwestern Canada West (now Ontario), was a particularly desirable location and the Boston abolitionists had been generous with their financial support. Two of the founders of Dawn, Hiram Wilson and Josiah Henson, had been in Boston within the month and both had enthusiastically touted the success of the settlement.[7] With this fresh on everyone’s mind, it was decided that this would be an ideal destination for the fleeing family. Josiah Quincy Jr., the mayor of Boston, and brother of Edmund Quincy, was able to secure a railroad pass from Boston to Albany, New York, for the Brown family. As an additional safety precaution, the Browns were accompanied by Reverend Young, whose professional demeanour and white skin allowed him more clout in spear-heading the trip.[8]

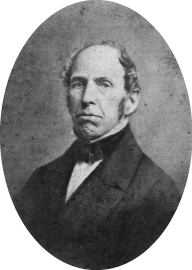

Francis Jackson was one of the most prominent anti-slavery activists and beloved among his peers. More than just a moral theorist, he is credited with welcoming many runaways into his home.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62 -27877.

It was a relief to have an uneventful experience on the more than seven-hour trip to Albany. The landscape that rushed by the train’s window would have offered endless fascination for the Brown children. Rolling hills transformed into small mountains, all subtly coloured the entire spectrum of shades of grey. Inexplicably defying the dictates of nature, giant irregularly shaped evergreens competed with hardwood trees for toeholds in the rock fissures. Clusters of white-barked birch trees were occasionally sprinkled into the mix. The new freight house at the Greenbush Station opposite Albany and at the end of the route was a man-made marvel. With walls nineteen feet high and nine feet thick, the building covered two-and-a-half acres and was said to have cost $100,000 to build and was considered to be the largest building in the United States.[9]

It was with this backdrop that they encountered their first snag, which delayed their progress for a full day. The cumulative fare for the next segment of the journey, at $3 per person or four cents per mile, was costly for the group of twelve, and Reverend Young tried to appeal to the person in charge, a Mr. Goming, to have compassion for the Brown family. It was not unknown for the railroad companies to be flexible, in fact, in the same month they had waved the fee for a carload of students from The New York Institution for the Deaf and Dumb travelling home from Albany to Buffalo to visit family and friends. Steamboat captains on the Hudson River made a like offer and the proprietors of the eatery in the Albany Rail Road House refused to accept payment for the students’ meals.[10] However, Mr. Goming refused to give free passes on the grounds that the company he worked for was opposed to issuing them to blacks. Reverend Young pleaded their case and implored Goming to reconsider. After considerable begging, Goming relented — in part. He finally agreed to give them free passes from Schenectady to Syracuse, leaving Young and the Browns to solve the dilemma of getting from Albany to Schenectady.[11]

It was an “unpleasant task,” but Reverend Young eventually succeeded — perhaps with a competing railroad company — in getting a set of passes for the relatively short eighteen-mile trip from Albany to Schenectady. The trains on this route were immensely popular, sometime carrying between 450 and five hundred passengers crowded into nine of the eight-wheeled passenger cars on a single trip.[12] The group wedged themselves in until they reached Schenectady, where they boarded yet another train for the one-hundred-mile-plus trip to Syracuse, arriving at midnight on Saturday, July 17. They were forced to remain in that city for two days. There would have been a certain comfort for Isaac Brown and his family there. Syracuse was a noted Underground Railroad safe haven with leaders like Jermain Loguen, Reverend Luther Lee, Samuel May, and John Wilkinson.

Lee worked as a lecturer for the New York State Anti-Slavery Society in 1839 and 1840 before becoming a Wesleyan minister, and, in 1843, led his congregation to break away from the Methodist Episcopal Church because the latter refused to speak out against slavery and allowed slave owners to be a part of their congregation. They constructed their own church, which today remains the oldest building in Syracuse. Lee was also an executive member of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society along with Lewis Tappan, William Whiting, Charles B. Ray, and George Whipple, most of whom had some connection with the flight of Isaac Brown.[13]

Reverend Lee would have been able to share some stories of his Underground Railroad activities that would have resonated with Isaac Brown. One in particular would be of a fugitive who was enslaved on a plantation where Henry F. Slatter had taken fifty blacks on speculation.

Lee was well-connected with officials from the railroad company in Syracuse. Because of that, he was always able to secure free passage for any runaways who passed through the city simply by writing “Pass this poor colored man” or “poor colored woman,” or in a case like Isaac Brown’s, “poor colored family.”[14] Lee claimed that all of the conductors understood the pass and never challenged it. Their orders would have come from their superiors including John Wilkinson, a lawyer and president of the Syracuse and Utica Railroad.[15]

Wilkinson’s anti-slavery sentiments evolved over time. Seventeen years previously, he had been a vocal attendee at an anti-abolition meeting, at which he chaired a committee to protest those “obnoxious” advocates of immediate emancipation who:

[H]ave caused great excitement and alarm in the States where Slavery exists, and tend to endanger not only the welfare and happiness of the white population in those States, and the well being of the Slaves themselves; but threaten the subversion of the Union under which this country has for more than half a century enjoyed a state of prosperity and happiness unparalleled in the annals of history.[16]

Referring to Abolitionists as “misguided” and “fanatics and incendiaries of a dangerous order,” Wilkinson condemned the formation of abolition societies and the publication of emancipation newspapers and pamphlets.[17] Mercifully, his stance had softened throughout the years or else the recent publication of the pamphlet The Case of Isaac Brown and the attendant media coverage would have surely enraged Wilkinson enough to turn Isaac Brown over to the slave hunters. In coming years Wilkinson would speak out, advocating the prohibition of slavery in all United States territories and against allowing any law that would force the apprehension and surrender of fugitive slaves without allowing them due process.[18] He would also grant permission for a mass meeting of an estimated 1,500 people to assemble in the magnificent new domed engine house of the Syracuse and Utica Railroad Company to celebrate the anniversary of the famous “Jerry Rescue” in which a large crowd fought off federal marshals and local police officers to rescue a fugitive slave who had been arrested and threatened to be returned to the South.[19]

With his recently matured sympathy for runaways, Wilkinson was easily persuaded to provide a free pass for the Brown party to take a train from Syracuse to Buffalo. At midnight Monday, after a two-day pause to refresh themselves, the group boarded the train heading west on a rough route that was long and crooked with steep inclines. The plan was that when the cars stopped along the route at Rochester, Brown and Young were to meet with another man who would have confirmed the validity of their pass. However, Young misunderstood the directions he had received from Wilkinson and failed to meet the person. He had yet to grasp the fact that New York State had a huge patchwork of unaffiliated railroad companies with different officials running each one. As a result, the conductor from the Attica and Buffalo Rail Road made an insolent and heated public refusal to let them proceed on their stretch of track without paying. Skilled in the arts of dealing with that type of behaviour, Young produced the pass, which was signed by Wilkinson that read “to Buffalo” and responded to the irate conductor in a manner intended to cause embarrassment to the hard-hearted railroad employee, who stood his ground.[20]

Disappointments and challenges were becoming increasing burdens for the travellers. But Providence intervened to lighten the load in the form of a man who took a keen interest in the beleaguered group. Upon having his sympathy aroused by Isaac Brown’s heart-wrenching story, the gentleman, a stove-maker by trade, wrote out a pledge to send a heavy, good-quality stove to the Browns once they had reached Canada. The gift from this stranger would be worth between eighteen and thirty dollars, an amount that the intended recipients could never have afforded.[21]

With their spirits buoyed by this random act of kindness, Reverend Young purchased tickets and the entourage continued their trip to Buffalo on Wednesday July 21, where they were met with another pleasant surprise. The conductor, with whom he had earlier quarrelled, met them at the station, and, in the presence of a lawyer, apologetically refunded the money for their fare. This welcome and unexpected turn of events with the promises of Canada almost within their grasp should have been the ultimate gratifying gesture as the Browns were soon to leave the worries of the United States behind. But Susannah had taken ill, worn out from everything they had experienced. Unable to continue immediately, they were forced to spend another two days in Buffalo.

The timing was unfortunate as there had been a major racial incident near the city only five days previously. An Alabama couple, accompanied by their female slave, were on an excursion to see one of nature’s masterpieces, Niagara Falls, and were about to depart when, according to one report, between twenty and thirty blacks rushed the train in an attempt to liberate the girl. Some threw obstructions on the railroad tracks while others rushed the passenger car. The engineers and conductors rushed to assist the slave-owner and violence erupted. Other reports said that a black man was attacked after simply asking the slave girl if she voluntarily wished to go back with her master. Other blacks joined in to defend their fellow. An Alabama newspaper reported that the girl did not want to leave her mistress, while a Washington newspaper reported that the girl had told a hotel chambermaid that her mistress treated her badly and asked that the coloured citizens assist her in escaping. Whatever the facts were, all agreed that the rescue was unsuccessful and several people were seriously wounded. In a general retaliation later that day, a mob fired gunshots and burned down a house that was occupied by blacks.[22]

Perhaps it was the resulting tension that influenced Reverend Young and the Browns to seek a boat headed southwest to cross Lake Erie rather than take one of the nearby ferries that crossed the Niagara River. With Susannah regaining her strength, Young proceeded to plan the final leg of the journey, and boarded a Great Lakes boat, the St. Louis, and asked the clerk if he could book passage. The clerk said if it were up to him he would not take blacks, explaining that he had done it once and the man turned out to be a slave. The Southern press learned of it and printed the story to the detriment of the ship’s business. When the vessel’s master, Captain Wheeler, arrived, he contradicted his clerk, stating: “I will take them. I had as soon take knot heads as pig iron.” At first pretending not to show any offence, Young waited until a group of curious onlookers gathered closer, and, using the psychological technique that he had recently honed on a train’s conductor, softly asked: “Captain, what kind of a civilization is that which teaches you to speak in such disrespectful term of your fellow-beings?”

The embarrassed captain dropped his head and said that he would take them across the lake. A man of unflagging principle, Reverend Young declined, stating: “I have the honour of travelling with a select family, and if you are a fair representative of the character of the company and crew of this boat, I shall not go.”[23] At that, he took his valise and returned to shore, while two crew members tried to persuade him that they would be well treated. Young replied to the well-intentioned men that he would not cross Lake Erie until he could find a civilized captain. It was not until the next day before Young found his man — Captain Croton Shepherd of Ashtabula, Ohio, who commanded the steamboat Cleveland. To his delight, Shepherd had heard of Young’s dressing down of Captain Wheeler the previous day, and in repayment for that pleasure Shepherd would gladly take the entire Brown family at no cost. Young would have to pay his own fare, but the Captain promised him that he could join him in his state room at any time without charge.

It was an enjoyable forty-eight-hour trip across Lake Erie with Captain Shepherd and his crew before they entered the mouth of the Detroit River, passed by the old British Fort Malden in Amherstburg to their right, and the island covered with birch and beech trees that the early French settlers had called Bois Blanc to their left, and finally pulled into the dock in Detroit, Michigan. Only minutes and the narrow Detroit River separated them from the Canadian shore at Windsor. However, it took three long days before they could find a boat that intended to travel up the river to Lake St. Clair, their intended destination within the British colony.

While waiting, the Browns and Reverend Young were joined by Hiram Wilson, the missionary to the blacks in Canada, who had prepared a house for the family next to his own in the Dawn Settlement. He had made the sixty-mile trip to Detroit to guide them the rest of the way. Forty-four-year-old Wilson had a long history of selfless service to fugitives. After graduating from the Oberlin Theological Seminary in 1836, he travelled to what was then Upper Canada to observe the progress of blacks there. Returning the next year as a representative of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he began a quest to raise money and establish mission schools throughout the province. By 1839, he had established ten schools with fourteen teachers who instructed three hundred students. With the zeal and dedication of an Old Testament prophet, he travelled thousands of miles, criss-crossing the land separating the Great Lakes. Many of his journeys were on foot, covering fifty miles per day. He carried a valise containing a bit of food and he took shelter for the night in whatever household would offer it. Generous beyond reproach, he and his family lived a life of poverty and want.[24]

Wilson had been in Boston when Isaac Brown had first been arrested in Philadelphia, attempting to raise money for the mission dubbed “The British American Institute” that he had helped to found as part of the Dawn Settlement. He had sympathy for the man, as he did for everyone who had suffered the curse of slavery. But Wilson was now the recipient of the profound sympathy of others. Earlier that summer, his beloved wife Hannah had died at the Dawn Settlement. During her final illness, her friends asked if they should not immediately send for her husband who was in Boston, many miles away. She refused, knowing that “he was engaged at his post, pleading the cause of the poor and despised descendants of Africa” and that for the sake of doing good she would sacrifice his company.[25] She had been the one constant in his life: his partner in seeing to the needs of the fugitives who came to their door, a teacher at the mission school, and the devoted mother of four small children. It was not until he had arrived in Detroit on his way back from Boston in late May of that year that he learned of her death. With a heavy heart, he hurried home, arriving eight days after her funeral.[26] Taking but a little time to indulge in his own grief, he soon returned to his calling. Within weeks after having received a letter from Francis Jackson in Boston alerting Wilson about the Browns’ flight, he returned to Detroit to meet them, now safely in the care of Wilson’s anti-slavery friends.

Among those friends was a celebrated lawyer and member of The Michigan State Antislavery Society, Charles H. Stewart. Both he and Hiram Wilson were among the founders of the organization. Stewart had recently run for a seat in Congress on the Liberty ticket, the same party that others, who had helped Isaac Brown, had been associated with.[27] Five years earlier, in a move that had elevated his status among abolitionists on both sides of the border, Stewart had spoken out in protest against the British authorities extraditing Nelson Hackett, a fugitive slave who had been captured in Canada West. When vocal objections failed, Stewart secured a writ of habeas corpus for the runaway, when the latter was transferred from Canada to a Detroit jail cell. The official charge against Hackett was that, in making his escape, he had taken his master’s gold watch and a beaver coat, as well as a horse and saddle. Although Hackett pled guilty to those charges (a confession that he later recanted, claiming that he had been beaten in the head with the butt of a whip and a large stick during his interrogation), it was felt that, as it was in the case of Isaac Brown, this was only a pretext for having the slave returned to bondage. Hackett was returned in shackles to his master in Arkansas, despite all efforts of Stewart and many others on his behalf.[28] According to one of his fellow slaves, upon Hackett’s return to his plantation, he was kept in chains and fetters, flogged unmercifully on several different occasions with the number of lashes ranging from thirty-nine to 150, and finally dispensed to the interior of Texas.[29] Stewart and Wilson had grave concerns that history could repeat itself.

Perhaps Canada was not the safe haven that everyone had assured Isaac Brown it would be. The worries, which were constant companions, increased. And he would still have to eventually cross the Detroit River to the Canadian side to catch a boat bound for the Dawn Settlement. To take that first step, he would have to take the ferry operated by a known slave hunter named Lewis Davenport, who had returned the chained Nelson Hackett part of the way back to Arkansas. Davenport’s hard-hearted reputation was further established when he was awarded the contract to build the scaffold and gallows for the last public hanging in Detroit.[30] Terrifying him further were the slave hunters who had been regularly patrolling the Detroit docks for more than a week, looking for runaways.[31]