Chapter Eight

Rescue the Slave

Freemen arouse ye, before ’tis too late,

Slavery is knocking at every gate:

Make good the promise your early days gave,

Christian men, Christian men, rescue the slave.[1]

— From the Provincial Freeman

After two days’ rest, Samuel Young departed Dawn for the seat of government for British North America’s provinces, Canada West and Canada East, in Montreal, presided over by Governor General James Bruce, who bore the aristocratic titles 8th Earl of Elgin and 12th Earl of Kincardine, but was more simply known as Lord Elgin. Young carried copies of the detailed pamphlet of the case that had been printed in Philadelphia, as well as some letters of introduction that had been provided by Isaac T. Hopper, Charles H. Stewart, and Hiram Wilson, which he could present to eminent figures in London, Hamilton, Toronto, Kingston, and Montreal. These figures were selected as those whose names would carry weight with the governor general. It was decided that Samuel Russell/Isaac Brown would not make the trip, fearing that if things did not unfold as hoped, he could be arrested by an official who might easily be deceived if he was unaware of all of the facts. Experience had taught them a valuable lesson.

Hiram Wilson transported Young sixty-five miles by horse-drawn carriage to London, where they parted, promising to meet upon Young’s return and to tour other black settlements in Canada West. Young had a warm reception in Toronto, where he met with the influential Colonel John Prince, who had the prestigious position as Queen’s Counsel and was a long-time elected member of the House of Assembly. Prince had been partly responsible for the return of Nelson Hackett to the United States and was generally intolerant of blacks, so it was now critical to have him on Isaac Brown’s side. It was ironic that Charles Stewart, who had once opposed Prince in the Hackett case, now provided Young with the letter of introduction to his former foe. In this case, Prince gave his support to Brown and encouraged Young to proceed to Montreal.

Young was cordially received there by all of the government officials, with the exception of a chilly silence from Attorney General Henry Sherwood from Canada West, who offered no assistance.[2] Undeterred, Young was well received by Major Campbell, the private secretary of Lord Elgin, and by Attorney General William Badgley of Canada East (now Quebec). Badgley, being from the Francophone province and having regularly witnessed the disharmony between two cultures, perhaps had more empathy for Brown, and thoroughly investigated the terms of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty that addressed the legal issue of extradition between Britain and the United States. After studying the law and the legal documents that Young provided, Badgley gave his assurance that Isaac Brown “was as safe as he would be in London, England” and would not be surrendered to Maryland officials.

The timing was fortuitous. Within two days, two emissaries of the governor of Maryland appeared in Montreal and were granted an audience with Lord Elgin. They demanded the surrender of Brown, but were rebuffed. A defiant Reverend Young met the dejected men as they left the office of the governor general and told them of his part in accompanying the fugitive slave to Canada. “At this announcement they were as fierce and ravenous as wild beasts, and said they would soon lynch him if they had him in Baltimore.” Young set aside his usual calm demeanour and invited them to display their bravery on the spot, but the southerners discerned a rising tide of indignation among a gathering crowd of Canadians and decided that discretion was indeed the better part of valour. Still seething, they snarled that they would no longer speak to anyone “who sympathized with niggers” and went on their way, all the while followed by a group who ensured that they would not turn around.[3] An abolitionist acquaintance of Young, who stayed at the same hotel as these two, remarked that prior to their trip to the Government House they were quiet and peaceable, but later “were like mad-men” because Young had thwarted their purpose. They claimed that the governor of Maryland had promised them a reward of $1,000 if they returned with Brown.[4]

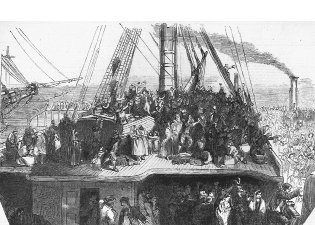

Of the one hundred thousand Irish immigrants who sailed in overcrowded “coffin ships” across the Atlantic to Quebec in 1847, it is estimated that one in five died. The image is from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, January 12, 1856.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-132543

Samuel Young prepared to leave the city in triumph. The city was beautiful with its Old World charm, but Young was eager to share the news of his success, see other black settlements, and finally return to his own family where he could make a final decision on moving to Canada. Before departing, he took notice of an overwhelmingly vindictive epidemic that was attacking Montreal. An outbreak of typhus or “ship fever,” as it was sometimes called, was spreading throughout the desperate masses of immigrants to Canada who had fled the potato famine in Ireland. It was highly contagious and quickly spread in every filthy and crammed hold of a ship that left the British ports carrying those “peasants” who were already suffering the effects of famine and exhaustion. Many of those, who witnessed the many burials at sea and survived the voyage in what came to be known as “coffin ships,” carried the disease into the crowded harbour at Montreal, unleashing it on the rest of the city. Within about twelve days of exposure, the affected began to suffer with fever, headaches, muscle aches, and weakness, followed by rashes on the torso and limbs. After suffering for up to ten days, as many as six thousand people succumbed to the disease. Montreal was not the place to tarry in the summer of 1847, but Reverend Young, being the person that he was, spent some time giving comfort to the afflicted before taking his leave to stay on schedule to keep promises made to friends.

After rejoining Hiram Wilson as previously agreed, the Long Island minister was able to relay the story of Isaac Brown to a large group in Toronto, who revelled in his account of his reception and success in Montreal. Forty-six Toronto black residents were inspired to make public their appreciation by composing a letter and having it printed in The Globe. Part of their motivation was less lofty, as they also attempted to shame Sherwood, the attorney general from their own province, whose duty it was to address the case, for his lack of interest or support.

To the Honourable Wm. Badgley, Attorney General of Canada East, &c., &c.

We, the undersigned, coloured citizens of Toronto and vicinity, loyal and dutiful subjects of her Majesty’s just and powerful government, take pleasure in availing ourselves of this opportunity to express to you our sincere thanks for the courteous and Christian-like manner in which you recently received our late kind and worthy friend, the Rev. Samuel Young, of New York, who is known to have been deeply interested for the protection and welfare of our afflicted brethren in the United States of America, especially as evinced in the case of the innocent and grossly injured and persecuted man, who has lately found his way to this asylum, from the midst of the republican despotism and slavery.

Forasmuch as we deeply sympathised with our honoured advocate and brother, above mentioned, in his philanthropic and praiseworthy exertions for the deliverance of the innocent unoffending fugitive from the bloody grasp of the avaricious man-thief, we cannot find language adequate to express fully our grateful obligations to you for giving him the hand of friendship, and in his worthy course, such candid and earnest assistance as could be looked for, only in an official gentleman possessed of a noble and philanthropic mind.

May the Divine blessing attend you in all the relations you sustain, even to the end of your earthly pilgrimage — and especially in the discharge of the duties which devolve upon you in your official capacity.

(Signed)W. R. ABBOTT, and forty-five others

Letter from the Coloured Citizens of Toronto to Attorney General Badgley. The Globe, December 11, 1847.[5]

Energized from two days filled with accolades and warmth in Toronto, Young and Wilson boarded a steamboat at the Lake Ontario harbour and proceeded to Hamilton, reaching port at sundown on August 24. Reverend Young’s recent fame had already spread to that city and he was met by a messenger, who requested that he come and address a crowd eager to hear first-hand details of the Isaac Brown saga. He did not disappoint, and kept the audience spellbound until late in the night.

The next morning, the two ministers climbed into a stagecoach bound for Waterloo, a trip of forty miles. Their destination was a gateway to the old and established scattered black settlements within the area known as Queen’s Bush. After a night’s sleep in Waterloo, they began their sight-seeing expedition on foot along the crooked roads, littered with stumps, rocks, swamps, and gullies, and small bridges made of trees laid sideways. They were greatly impressed with almost everything they saw on the walk, which extended several miles — the neat log homes, the livestock, the bountiful crops, and the quality of the wheat harvest that was nearing its end. They took particular enjoyment in meeting the residents and listening to their tragic histories of enslavement and to the triumphant stories of escape and freedom.[6]

Upon reaching the mission house known as Mount Hope on Saturday, August 28, they were welcomed by kindred spirits, missionaries John Brooks, originally from Massachusetts, and Fidelia Coburn from Maine. Miss Coburn had previously worked with Hiram Wilson at the British American Institute and both, like Wilson, continued to labour with the meagre support of the American Missionary Association, a few other anti-slavery societies, and the largesse of charitable donors, primarily from New England.

Mr. Brooks’s home was comfortable and the nearby building where he preached and taught was described as “a noble school-house, fit for a church, or a large dwelling.”[7] Miss Coburn lived and worked at her own mission, Mount Pleasant, about three miles away. That day, however, the two missionaries were together, Brooks having come to assist his female colleague who was becoming overwhelmed with the pressures of her situation. Reverend Young and Reverend Wilson sensed another reason, and advised the couple that it might be wise to get married, as they thought they “might be more useful.”[8]

That evening, Samuel Young was called upon to share the story of Isaac Brown to a large gathering at Mount Hope. He was to preach the next morning at Mount Pleasant, but had to decline due to a severe headache. By afternoon it had subsided enough for him to fulfill that promise. The next day, Monday, August 30, he felt fit enough to speak for three hours to another large and responsive crowd. But he had over-taxed himself and an illness brought on by what they logically suspected was exhaustion started to overcome him.

By Tuesday evening, the two friends decided it best to begin their journey home. The twelve-mile walk from Waterloo to Mount Hope had only taken a few hours the week before, but the return trip was much slower. Two days were lost since Reverend Young was unable to travel. He was quickly losing strength as the strange malady took over. On Friday, September 3, they finally reached Waterloo, but could go no further and hired a room at Bowman’s Tavern.

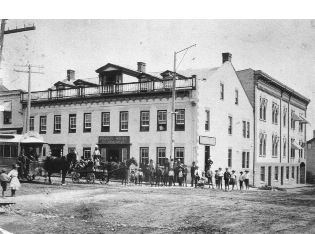

Reverend Samuel Young spent his final days at Bowman’s Tavern, also known as the “Farmer’s Hotel.” Although the original tavern burned to the ground in 1850, it was replaced by a similar structure pictured above.

Courtesy of Ellis Little Local History Room, Waterloo Public Library. Item ID: E-3-12.

A doctor was summoned as soon as they arrived and he rushed to administer what medical treatment he could. By Monday, the patient was getting worse despite the care of a second, more accomplished doctor. Sensing that this might be an illness for which there was no cure, Reverend Young grasped Hiram Wilson’s hand and asked his friend not to leave him until he either recovered or was in his grave. He suffered with a burning fever and a debilitating headache that a cool cloth could relieve but little. The doctors were baffled as to how to treat him. On Wednesday, Young started to become delirious and increasingly unaware of his surroundings, symptoms that only became worse over the next four days. At dawn on Sunday morning, September 12, with Hiram Wilson at his side, as he had constantly been for six days, Samuel Young peacefully and silently took his final breath.

A panic had already set in among the people of the town, fearing contagion from whatever had claimed Young’s life. Despite being physically and emotionally drained, Hiram Wilson rushed to find an owner of a horse and wagon, who would agree to carry the remains to Mount Hope for burial. Wilson judged that place to be most appropriate, lying in the black settlement where he had so recently shared the story of one of their fellows whom he had aided to freedom. By 5:00 p.m., Wilson had found a team and an open wagon to carry the coffin. A Danish man — who incidentally was exceedingly proud that the king of Denmark had moved to abolish slavery before the king of England — volunteered to act as teamster, and a black man, who had came from Mount Hope to check on Young’s health, also agreed to accompany the body. This sombre entourage travelled seven miles until darkness overtook them. The living were offered lodging at the home of a Pennsylvania Deutch family, the dead was sheltered in the barn. Unbeknownst to all, a group of twenty-six black men upon first learning of Reverend Young’s death left a campground meeting near Mount Hope at 3:00 a.m. to walk the fifteen miles to Waterloo to carry the corpse of the man they considered a hero to their race to the sacred ground where they buried their own loved ones.

The next morning the humble funeral cortege continued on. In the early afternoon, Hiram Wilson delivered the eulogy to a large black congregation that had travelled from across the Queen’s Bush. The chosen Bible text was taken from the Book of Revelations: “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord.” All joined together to sing a song that Wilson had hastily written for the occasion:

Friend of the friendless and forlorn,

Kind brother to the bleeding slave,

Thy name we love — thy absence mourn,

We yield thee to the Martyr’s grave.

Here on Mount Hope thy dust shall sleep.

Till the last trump of God shall sound,

Here round thy grave shall pilgrims weep,

And grateful tread this sacred ground.[9]

There was a gentle rain and many tears as they laid him to rest. Conspicuous among the mourners was the solitary figure of the black man who, along with Hiram Wilson, had brought the body to that place after having walked to Waterloo the day before with the intention of helping to attend to Samuel Young. Upon learning that he was dead, the man had become inconsolable. In Wilson’s words “those scenes were solemn and impressive and will not soon be forgotten.”[10]