Epilogue

The Last Mile of the Way

When I’ve gone the last mile of the way

I will rest at the close of the day;

And I know there are joys that await me,

When I have gone the last mile of the way.

— Johnson Oatman Jr., 1908

Although time must have seemed to stand still during the crisis of the beginning of the 1860s, life continued with all of its twists and turns. Jacob soon took a wife, Rosanna Jones — commonly called Annie, and the couple moved into her parents’ home. They quickly filled their lives with children of their own, first Annie Maria, then Robert James, followed by Arabella.[1] Jacob was soon to learn the pain that his parents and sister had experienced when his three-week-old daughter died on August 20, 1872.[2] A year later, yet another daughter died after a three-month illness in which she wasted away, malnourished and emaciated.[3] Two years after that, his eldest, Annie, died of consumption at the tender age of eight.[4] By 1882, only Robert was left from his first children, but he was (later) joined by siblings Theodore, Alfred B., Florence, Kirby Herbert, and Jessy.[5] Jessy was only to live for ten months when on February 4, 1882, after suffering from a lung disease, she joined her sisters in death.[6] Jacob spent the remainder of his life in Chatham, living at a variety of places in Chatham’s east end, working as a whitewasher, plasterer, and a common labourer.[7] His first wife, Annie, died of apoplexy on September 30, 1896, at the age of fifty-three.[8] Two years later, Jacob married a California-born widow, Clarissa Woodey.

The elusive Leonard Russell resurfaced in the 1870 census of Detroit, now married to twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth Johnson. His bride was Canadian-born, the daughter of parents from Kentucky and Virginia who had fled to the safety of the British Dominion. The couple were the proud parents of three daughters: Carlin (Catharine), seven; Louise (Elisa), six; and Ida (Idell), three. They were all listed by the census taker as having been born in Michigan. Leonard was recorded as a labourer, age twenty-nine, and unable to read or write.[9] In 1871, the family lived at 81 McComb Street before moving down the same street to 366 McComb, from which base he continued his work as a whitewasher.[10] Tragedy struck the household before the end of the decade when the young wife and mother, who had lived in the United States for thirteen years at the time, died of consumption at age thirty-five in December 1879.[11] In 1880, the now-widowed Leonard remained living in Detroit with his three daughters, along with boarder Candis Salter, who supported herself by taking in washing and ironing. Catharine, now seventeen, was in charge of keeping house, while her sisters attended school. Elisa, the middle child, was listed as the only child born in Canada, while her sisters were born in Michigan.[12]

On January 5, 1887, Leonard was awarded a contract for whitewashing and cleaning the jail in Detroit.[13] Nearing the end of that year he crossed over the Detroit River to Windsor and at age forty-seven married a widow, Josephine Lee Goodman, who was ten years his junior.[14] The couple were permanently drawn to the Canadian side of the border, and, by 1891, were living in Windsor. Their home was filled with family members — Leonard’s twenty-seven-year-old daughter from his first marriage, Harriet; his son, John H., eight (by his new wife); his wife’s brother Levi Lee; Lee’s wife Savilla; and their infant daughter. By 1911, Leonard and Josephine had a house to themselves at 287 Howard Street where they peacefully spent their last years together until Leonard’s death on August 26, 1917. The remainder of Samuel and Susannah Russell’s children prove much more difficult to trace.

So many unanswered questions surround what became of the family in the latter half of the nineteenth century as their names slip away from the public records. Could it be that scarlet fever had not finished its fiendish assault in the weeks that followed the January 1861 census taker’s visit to the Russells’ homes? The Chatham Weekly Planet paid little attention to the epidemic and remained strangely silent on the subject in issue after issue. It was not until March 7, 1861, that an article mentioned: “for some time past the scarlet fever has been raging with great fatality in this town. The number of deaths that has occurred is startling — many of them taking place under circumstances that are particularly distressing.” The article went on to state that one family lost four children within days and many others had lost one or two. The “most melancholy bereavement” was assigned to a family named Dolsen who had lost a daughter, then her mother within two days, and the two remaining children were gravely ill. The Russells and every other person who lost loved ones would have taken issue with the writer’s insensitive assessment — however inadvertent his intent may have been — that any one family’s tragedy was more profound than another’s.

Even more intriguing questions are raised upon browsing the names of those who surrounded the Russell family. At the time that they squatted upon the lands of the Raleigh Plains in 1857, their nearest neighbour was a black man named Edward Brown. Living next door to Jacob and Rebecca Russell in Harwich in 1861 was a Willis and Mary Brown whose children included a daughter named Lucinda.[15] Coincidence, perhaps — after all, “Brown” is one of the most common surnames in the English language — but it tugs at the emotions to think that perhaps some of the Brown family from Maryland were eventually reunited in Canada.

Most appealing of all is the hope that perhaps Samuel and Susannah Russell eventually saw the two of their eleven children who did not accompany them to Canada after they left Maryland and ultimately made a hasty flight from the gates of a Pennsylvania prison. Did they ever meet again on one side of the border or the other? Even the question of their first names remains elusive. Given the most common of all naming patterns, is it fair to guess that one of the sons would have been named Isaac?

An investigation into the Records of the Assistant Commissioner for the District of Columbia that contain outrages against blacks in the aftermath of the Civil War reveals the account of a Calvert County incident where a white man threatened to kill a “colored” Isaac Brown because the latter had “Union sentiments.” Brown was forced to flee his home looking for safety.[16] Whether or not this was the son or another relative, the story paints yet another lasting image of the pain and the uncertainty that surrounded the lives of blacks even after freedom was a legal reality. Other attacks in Calvert County, including a white man being beaten and shot at for the offence of having voted for Abraham Lincoln, a black man assaulted for not addressing a white man as “Master,” and multiple charges of black children being forced into apprenticeships despite the protests of their parents, further demonstrate the uneasiness that any remaining members of the Brown family would have felt.[17]

The Somerville family decided to use the traditional spelling of their surname on their memorials in the Middleham Church cemetery.

Photo by the author.

Alexander and Olivia Somerville, Isaac Brown’s former master and mistress, lost much of their fortune during the Civil War, including their thirty-two slaves who ranged from infants to people in their mid-seventies.[18] Alexander survived the war by only a few months, dying on August 28, 1865, just days after his fifty-ninth birthday. His simple granite tombstone in the peaceful, treed cemetery of the historic Middleham Chapel has fallen off its base and offers to the family the comforting words “Blessed are the dead that die in the Lord.” Olivia survived her husband for another nine years. Her tombstone, discoloured by time and inscribed with the most well-known passage from the twenty-third psalm, stands beside that of her husband.

Middleham Chapel in Calvert County, the home church for Alexander and Olivia Somerville, is located just south of their farm.

Photo by the author.

Stained-glass window in memory of Alexander and Olivia Somerville at Middleham Chapel, Maryland.

Photo by the author.

The church itself, a relatively tiny brick structure constructed in the shape of a cross, rises on a slight incline and overlooks the cemetery and surrounding countryside. Already an aged building in the years that Alexander Somerville and his family attended, it is the oldest church in Calvert County, built in 1748 to replace a smaller log building that dated from 1684. The cost of the construction in the currency of the time was eighty thousand pounds of tobacco. It was for many years “a Chapel of ease” — a place of worship more conveniently located to serve those who lived at such a distance to make it difficult to attend the main parish church, which could be several miles away.[19]

The home of Alexander Somerville was within an easy wagon ride to Middleham Chapel and he and his family were respected members. Many of them are also remembered through their markers in the cemetery, but a beautiful stained glass window, which is the focal point within the sanctuary, serves as a special memorial to Alexander and his wife.

An even more striking monument belongs to Hope Hull Slatter, the former slave trader who, along with Somerville, was prominently featured in the nightmares of Isaac Brown and his family. A year and a half after shipping Brown to Louisiana, Slatter temporarily retired from his vocation, selling his slave pen in Baltimore, as well as leasing his New Orleans pen to another Baltimore trader.[20] Despite being described as “a man of much intelligence and tact, of very gentlemanly address and considerable public spirit,” his occupation had made him “a sort of Pariah.”[21] According to an unidentified Baltimore source who reported Slatter’s death to the press and who claimed to not “entirely forget the maxim which enjoins to tread lightly o’er the ashes of the dead” the former slave trader wished to become an elite member of high society following his retirement. However, he discovered that, like the mythological garment soaked in the blood of the hydra that killed Hercules, “the shirt of Nessus was upon him and even gold was not potent enough to remove it.” Despite his mansion, impressive carriages, stables of beautiful white horses, and other manifestations of immense wealth, and despite his occasionally unrequited claims to be a friend of President James K. Polk, Slatter remained a social outcast.[22] He moved deeper south to Mobile, Alabama, where he purchased a grandiose building for $25,000 with the intention of turning it into a luxury hotel.[23]

The tomb of Hope Hull Slatter and family in Magnolia Cemetery in Mobile, Alabama. Photo taken in 1974 by Jack E. Boucher for National Park Service Department of the Interior’s Historic American Buildings Survey, Washington, D.C.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: HABS ALA,49-MOBI,226-.

It was in Mobile where he found his longed-for place in upper-class society and where his eventual death from yellow fever in the autumn of 1853 was publicly mourned. The Picayune of September 18 lamented the loss of “a man she can ill spare — a resident capitalist, and a liberal one too.” Both his occupation and his wealth ensured his everlasting place in history and both were responsible for his magnificent tomb in Magnolia Cemetery in the city where he spent his final years.

In sharp contrast is the absence of even the crudest memorial for one of the souls on whom Alexander Somerville and Hope Hull Slatter built their fortunes. There is no stone in Maple Leaf Cemetery in Chatham, Ontario, Canada, to mark the final resting place of Samuel Russell, previously the slave Isaac Brown. No obituary appears in the Chatham Planet or in those many newspapers that once covered his story so passionately and extensively. No last will and testament appears in the records of the Kent County Registry Office. Likewise, those things are missing for Susannah. Perhaps it was their lifelong struggle against poverty that denied those simplest reminders of their passage. The final public recording appeared in the 1864–65 County of Kent Gazetteer, in a section identifying “Professionals,” which listed Samuel Russell, Chatham, doctor. By the time that the 1871 census taker made his rounds through the east end of Chatham, neither Samuel nor Susannah was listed.

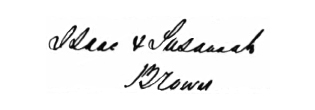

There was one more indirect record that mentioned the hero and heroine of our story, and it is most touching of all. On January 9, 1871, Sarah, one of the couple’s daughters, was married. Her marriage registration recorded that she was then twenty-six, still living in Harwich Township.[24] Given her age, she would be the same daughter identified as “Nancy” in the 1861 census. Her groom, Thomas Cundle, was a widower, born in England and several years her senior. He was a farmer and former stagecoach driver. Methodist minister Alex Langford performed the ceremony. Permelia Langford, the reverend’s wife, and Solomon Merrill, a Chatham hotel keeper whose tavern would bear his name for a century more, served as witnesses. The bride was only a child when she and her family first came to Canada, when they left their surname behind and became the Russells. But today, on the most special day of her life, unlike her siblings when they were in a similar circumstance, she used her birth name. When asked for the name of her parents, Reverend Langford entered the reply into the register:[25]