6. VII. 15

Dear Friend,

I did not take your remarks in the first letter as an expression of your personal statement. I contrasted your hypothetical thinking with my hypothetical feeling in hypothesizing that your remarks were your personal conviction. I reacted to this hypothesis, but I was well aware of the fact that it was only a hypothesis. I find it absolutely mandatory that we should give each other the credit to assume that neither of us wants to react in a personal way against the other; but we must, in order to get spontaneous reactions, adopt the attitude that each of us writes as if the one would think in this way, and the other feel in this way.

In order to avoid further misunderstandings, which I believe are looming, I would like, before going into your letter in more detail, to communicate the following views to you. In your first letter you write of two kinds of truth, and you will probably remember that I told you months ago that in my view everybody had to solve two mutually opposed problems. In accordance with my type, I have since called these problems “ideals.” Now I think that what you mean by two kinds of truth, and what I call two ideals, to be identical, but that this duality is actually not identical with the two types, although it seems to be so from the standpoint of each individual. Allow me, the concrete or objective [gegenständlich] (as Goethe calls it)86 or symbolic thinker, to make myself clear with the help of an image.

Once, on a motorboat trip, Fräulein Moltzer87 compared the introvert to a motorboat and the extravert to a sailing boat.88 Now let us imagine that we are going on a trip, you in the motorboat, and I in the sailing boat. Suddenly the wind drops, and I feel it as a violation when you leave in your motorboat. I insist on being taken in tow by you, which you in turn feel as a violation. On another trip you run out of gas, but I have a good wind, and we are faced with the opposite situation. As we want to stay together, and have learned from those experiences, you will now put mast and sail in your motorboat, and I a motor in my sailing boat. One can easily imagine a situation in which all his thinking no longer helps the introvert, and he has to feel, and conversely also a situation in which feeling himself into the object no longer helps the extravert, and he has to think.

Now, what I would like to call two kinds of truth or two different ideals is this: your ideal is to construct your motor in a way that a defect is as unlikely as possible, and that it uses as little gas as possible; my analogous ideal is to construct my sailing boat in a way that it can make use of the slightest puff of wind. Now this ideal is in contrast, for you as for me, with another ideal, namely, of coping with the situation by89 another appliance, so that the sailor can make the trip even without wind by using a motor, and the one in the motorboat without motor by using a sail. I would like to call the first ideal that of deepening one’s own personality, and the second one that of adaptation to reality.

These two truths probably run parallel to the two truths that Pastor Keller90 once derived for us from the gospels; the one puts the value of the individual soul above everything, the other the value of the realm of God. I do not think, however, that these two coincide with the various problems of the two types, for both types carry both ideals within themselves. Those ideals run directly counter to each other, because in both types the tendency to develop one’s personality prevents adaptation, and adaptation itself prevents the deepening of one’s personality. So each of the types believes that the other truth91 is the problem of the other type; this other truth only implies, however, that he himself should also solve the problem of the other, while it is not the other’s problem as such. What I called the ideal of deepening one’s own personality you call, in your last letter, the “typical ideal striving,” and the man who strives for it, “the ideally oriented.” Striving for adaptation to reality would then correspond to what you write in your first letter: “[M]an, ever mindful of his role as homo sapiens, tries to tame and control the irrational with the rational,” or to what you call, in your last letter, “the acceptance of the unconscious opposite.” You admit that typical ideal striving is one-sided, but it seems to me that in that one-sidedness there also lies what is important, valuable, and at the same time dangerous.

Nature always follows the principle of economy, so that one partner should not concern himself exclusively with perfecting his motor, while not using the good winds, or that the other should not only let himself be driven by the wind and stand still when the wind drops. Therefore, I would like to call, from my point of view, the one-sided striving for the perfection of one’s personality the irrational truth, and the striving for utilizing one’s faculties for adaptation to reality as much as possible the rational truth. I believe that there is a great danger in striving for the latter, namely, of becoming shallow, precisely because it runs counter to the tendency of deepening one’s personality. A motorboat made into half a sailing boat will lose its value, and vice versa. I can also imagine very well that a perfect sailor, who has developed his capacity for feeling-into to the highest degree, believes that he does not need the motor or thinking; and, conversely, that an expert with the motorboat, an intellectually superior person, has so much confidence in his gas supply and in the reliability of his motors that he does not want to be bothered by sailing or feeling. But you yourself say: “The more ideal the attitude of a type is, the more likely his plan will fail.” Both tendencies applied exclusively, therefore, harbor dangers, and yet both are beneficial, even necessary. And thus it perhaps boils down, once again, to the old maxim: “Do the one thing while not neglecting the other.”

If I now try to apply these views to your letter, what I call adaptation to reality is what you call “accordance with outer reality,” and the deepening of one’s one personality, “accordance with inner reality.” It is not from the fact that there are two types that the two kinds of truth are derived, in my view, but from the fact that for each of the two types there exist two kinds of reality, an inner and an outer one. Certainly the attitudes toward these realities, ideals, or truths taken by each of the two types are very different. I believe the introvert tries above all to develop his personality and to make inner reality harmonious, and he hopes to be able to adapt to reality in this way. The extravert, on the other hand, tries above all to adapt to outer reality, and hopes in this way to develop his personality. This may be the reason why the extravert is driven by something outside himself (by the wind, by feeling that depends on the object). He soon notices, however, that this one-sided attitude does not satisfy him. The introvert, on the other hand, has the force that causes movement (the motor) in himself, and is, eo ipso,92 less dependent on reality. Perhaps we can also put it like this: the conscious striving of the introvert aims at the development of his personality, at the creation of impersonal values, as you call it, and only the acknowledgement of the unconscious opposite leads him to an adaptation to reality. The conscious striving of the extravert, on the other hand, aims at adaptation to reality, and only acknowledging his unconscious opposite will lead him to develop his own personality. The interpretation on the subjective plane leads both of them to acknowledge the unconscious opposite and is, therefore, of the greatest importance for the extravert, too. I do not believe that the liberation of the extravert is possible through the interpretation on the subjective plane, however, because this interpretation leads him away from adaptation to reality. In my view, as I shall elaborate later, real liberation will be possible only if the ideal of adaptation to reality is also striven for.

It was very interesting for me to find that Goethe, that extraverted man, repeatedly expressed mistrust of carrying self-knowledge and the development of one’s personality too far, a mistrust I also felt in recent years toward certain trends in analysis. Thus, in a short essay, “Significant help from a single clever word,”93 Goethe wrote: “Here I confess that the great and so high-sounding task, ‘Know thyself!’ has always appeared suspect to me, the ploy of secretly allied priests who wanted to confuse man by making unattainable demands on him, and to lead him away from activity directed at the outer world toward false inner tranquillity. Man knows himself only so far as he knows the world, of which he becomes aware only in himself, and of himself only in it.” In a similar vein he wrote to Fr[iedrich von] Müller on 8 March 1824: “I maintain that man can never get to know himself, can never observe himself purely as an object. Others know me better than I know myself. I can only know and correctly assess my relations to the outer world, and this is what we should confine ourselves to. With all the striving for self-knowledge, of which priests and morals preach to us, we do not advance in life, and achieve neither results nor true inner improvement.”94 (Cf. also Goethe to Eckermann, 10 April 1829.)95

Goethe’s standpoint may be one-sided, but nevertheless it seems to me of value as a counterbalance to an overemphasis on the tendency to self-development.

Now, your letter has taught me that in my last letter I made a mistake in the form of a projection. Because my abstract thinking leads away from the object, I believed that yours did, too. But I have the impression that you have a similarly wrong view of the extravert, or I will at least assume it hypothetically. Your example of the teacher does not fit with how I see the extravert. If that teacher had really been selfless, and had really felt herself into her students, she would have felt and understood their drive for independence, and her very love would have forced her to honor it. The teacher’s reactions are in my opinion those of a selfish mother, not those typical of an extravert. She reacted in the way she did not because she was extraverted but because she wanted to be a mother.

From the fact that you chose this example, I venture to conclude that you believe the extravert does not consider the object in his abstract feeling (in his love), just as I believed the introvert did not consider the object in his abstract thinking. I would now like to apply one phrase in your letter to the extravert, in the following way:96 you think the extravert does not consider the object in his abstract feeling because it is an outright obstacle for him (owing to an unconscious power tendency, as you suppose), and that when he feels abstractly and selflessly, therefore, he does not really love the object at all.97 Exactly the opposite is the case. He loves the object through his feeling; indeed, it is indispensable for his feeling.

This is not so in the introvert. For him the object is an obstacle to his feeling, because his feeling disregards the object. But apart from this feeling, which disregards the object, the introvert also has sensation, which is as closely related to the object as is the representation of the extravert. You even said it was of a reactive nature. This sensation is in complete accordance with outer reality, while the feeling of the introvert is in accordance with his inner reality. This is not so in the extravert. His sensation of things is inadequate because of his lack of thinking. His feeling is in accordance with outer reality but not with his own inner reality. If the teacher’s feeling had been in accord with outer reality, she would have loved her students selflessly and honored their independence.98 She was not able to do this, because she still had an archaic attitude toward them. The feeling of the extravert is not influenced by the unconscious power principle, precisely because it is not in accordance with his inner reality, just as the abstract thinking99 of the introvert is not influenced by the unconscious search for pleasure.

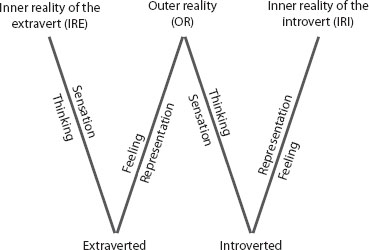

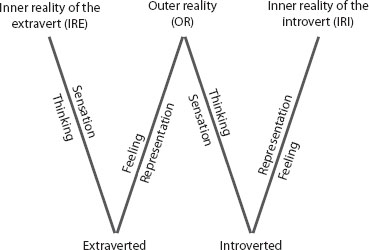

To make myself even clearer, I would like to use a graphical schema, although I can imagine that you as an introvert will have little sympathy for it. Outer reality is the same for both types, only their adaptation to it is different; inner reality is different for each of them, however. Guided by this idea I arrive at the following schema:100

I now realize that in my last letter I wrongly assumed that, since my tendency E[xtravert]-IRE is in accordance with inner reality, it would be the same for your corresponding tendency I[ntrovert]-OR. This was where I made a projection. I ask myself, however, if the introvert is not also inclined to assume that the tendency E-OR of the extravert leads as much to inner reality as his own corresponding tendency I-IRI. Since my thinking and sensation are in accordance with my inner reality, or let us say for short, egocentric, I assumed that yours were, too; and since your representation and feeling are in accordance with your inner reality, thus equally egocentric, you probably also found it suggestive to assume the same for me. In other words, we thought the tendencies E-IRE and I-OR on the one hand, and E-OR and I-IRI on the other, were identical, and this resulted in the feeling that the one did not do justice to the other, that the one was violating the other.

As far as this feeling of being violated is concerned, I naturally expected you to resist serving as an object for purifying my feelings, just as I resisted being merely thought. There is nothing irreconcilable in this difference for me, however. As a matter of fact, I have never felt this opposite nature of the two types as anything tragic but only saw a meaningful interaction of nature in it. What you felt as a violation, I felt as a meaningful force. I felt this force as unpleasant, or as a violation, only so long as I believed I had to submit completely to your thinking, to let my sailing boat be towed by your motorboat. The more I developed my abstract thinking, putting a motor in my sailing boat, the more I felt this force as salutary. It forced me to perfect my motor more and more. So I need not submit to your thinking but to my own, although I know that my motor will not be as perfect as yours for the time being. At the end of your letter you write yourself that I feel violated only so long as I violate my own thinking (instead of submitting myself to it). Vice versa, it seems to me that the introvert will feel the love of the extravert as a violation only so long as he believes he has to throw himself at the feet of the feeling of the extravert, to let himself be towed by the extravert’s sailing boat, or, as you put it, so long as he simply accepts the love of the other. The more the introvert learns to use his motorboat also as a sailing boat, the more he no longer violates his own feelings but tries to develop them instead (even if they are less sophisticated than those of the extravert), and the less he will experience the love of the extravert as a violation but more as a salutary force. Or, in short, the opposites are irreconcilable only so long as the extravert—because he himself cannot think—does not feel accepted by the introvert, and the introvert—because he himself cannot love—feels violated by the love of the extravert.

Now one could imagine that an arrangement between the two types could be found, in which the extravert accepts the introvert’s striving for the creation of impersonal values as an expression of love, and the introvert the love of the extravert as the latter’s impersonal value. In that way each would encourage the other in his one-sided ideal striving. But I do not think that this corresponds with our nature. The introvert who tries out this solution would probably soon ask himself, What use is the extravert’s love to me if he has no real impersonal values? And the extravert would ask himself, What use are the impersonal values of the introvert to me if he cannot give them to me with love? Therefore, I would like to expand your formulas for the two types as follows:

Introversion: I have to realize that my object, apart from its reality, is not only the symbol of my inferior pleasure to me, which I seek to gratify through it, but also the object of a higher conscious love, which I have to develop out of the unconscious, inferior pleasure in the object.

Extraversion: I have to realize that my object, apart from its reality, is not only the symbol of my unjust, tyrannical power to me, the approval of which I seek to get from it, but also an object through which I have to develop the conscious strength of my personality out of the unconscious, tyrannical striving for power.

In other words, the introvert not only must wish to develop himself in order to be loved but also must love in an active way in order to develop. The extravert not only must love in order to develop but also must have the wish to develop in order to be loved. For the time being, I would just like to show how I envisage the development toward this ideal state with the help of the image we used: the more the pilot of the motorboat perfects his motor, the more his boat will rise in the water and the more he will fly across it. Eventually his motor will become so perfect that he will exchange the resistance of water for that of the air and will fly on the water. And when he then also uses the sails as wings, he will rise above the water and actually fly. The sailor, on the other hand, will gradually perfect his yachtsmanship so that he will glide more and more swiftly over the water, and gradually he will learn to use his sails as wings. When he then also uses the motor, he will be able to rise out of the water into the air. Each perfects his own characteristics at first: the one makes a propeller out of his propelling screw, the other wings out of his sails. Then he reaches a point when he can develop further only if he accepts and takes over from the other the very thing by which he felt most violated at first, the sailor the motor, and the motorboat pilot the sails.

To conclude, a word on the subjectivity of the notion of beauty. It is part of the ideal striving of the extravert that he assumes not only a subjective notion of beauty but one that lies outside him, although it can be understood only metaphysically, a concept of absolute beauty, as Plato describes it in the Symposium.101 It is part of the ideal striving of the introvert that he assumes not only a subjective concept of truth but one that lies outside him, although it can be understood only metaphysically, the concept of absolute truth, or of the universally valid concept, as you called it. Going by motorboat is the search for absolute truth, sailing the search for absolute beauty. The universal confusion over the concept of beauty is as little a proof of the nonexistence of a metaphysical, absolute concept of beauty, as the equally great and universal confusion over the concept of truth is of the nonexistence of a metaphysical absolute truth. In his ideal striving the extravert needs the concept of absolute beauty, yet in order to adapt to reality he has to realize that the beauty does not lie in reality but in the feeling that he attaches to things. The introvert, in his ideal striving, cannot accept the concept of absolute beauty; he knows that the beauty lies only in his feeling. In order to adapt he has to assume, however, that the thing in itself can be beautiful and that an absolute beauty exists beyond his feeling.

In his ideal striving the introvert needs the concept of absolute truth, yet in order to adapt to reality he has to see that the truth is realized only in his thinking, not in reality. The extravert, in his ideal striving, cannot accept the concept of absolute truth; he knows that it exists only in his thinking. In order to adapt he has to assume, however, that there is a truth in itself, and that there is an absolute truth beyond his thinking. I once put the ideal in the following words: the introvert must strive for beautiful truth, and the extravert for true beauty.

Many other things could be derived from this, but for now only the following: Plato shows that only he who is driven by eros knows absolute beauty. Absolute truth, then, is probably known only by someone who is driven by phobos.

With best regards,

your Hans Schmid

86 The German psychiatrist and philosopher Johann Christian August Heinroth (1773–1843) characterized Goethe’s way of thinking as “concrete” or “objective” [gegenständlich]. Goethe fully agreed with this characterization, for example, in his essay “Significant help from a single clever word,” quoted by Schmid later on in this letter.

87 Maria Moltzer (1874–1944), daughter of the owner of the Dutch liquor factory Bols, became a nurse in protest against the misuse of alcohol. She was trained by Jung as a psychotherapist, became a member of his closer circle, and from 1913 on worked as an analyst in Zurich. Cf. Shamdasani, 1998b, pp. 103–6.

88 Here some lines inserted in the margin are heavily crossed out.

89 Crossed out: heterogeneous.

90 Adolf Keller (1872–1963), Swiss pastor and theologian, a member of the circle around Jung, later an active member of the Psychological Club. Cf. Jehle-Wildberger, 2009, and his wife’s description of him in her memoirs (Swann, 2011).

91 Crossed out: which seems irrational to him.

92 Latin for “by that very act (or fact).”

93 “Bedeutende Fördernis durch ein einziges geistreiches Wort” (1823).

94 Burkhardt, 1870, p. 1939. Friedrich von Müller (1779–1849) was chancellor of the grand duchy of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach and a close friend of Goethe (cf. ibid., Einleitung).

95 There Goethe said: “Throughout the ages people have said again and again that one should try to know oneself. This is a strange demand with which nobody has complied so far, and with which actually nobody should comply. With all his thoughts and wishes man is dependent upon the external, upon the world around him, and he is occupied enough with knowing it and making use of it to the extent that he needs it for his purposes. He knows of himself only when he enjoys or suffers, and thus he is taught about himself, and what he has to seek and to avoid, only by suffering or joy. But man is a dark being, by the way, and he does not know from where he comes nor where he goes, he knows little of the world, and least about himself. I do not know myself either, and God beware I should” (Eckermann, 1835, p. 376).

96 Regarding the following sentence, Jung noted in the margin: nonsense.

97 The following two sentences inserted in the margin.

98 This sentence added in the margin.

99 Corrected from: feeling.

100 Cf. Jung’s later fourfold diagram of the functions (Jung, 2012, p. 128).

101 Schmid may rather have thought of Plato’s Phaedo, however, in which Plato discusses the general essence of qualities in general, and “absolute beauty” in particular (the so-called problem of universals).