Japan has one of the world’s lowest fertility rates. In 2008, Japan’s population fell by a record 51,317. The shortage of children is so severe that the government has created a cabinet position to deal with the problem. Local authorities took to hiring matchmakers to encourage young people to find their soul mates. When they were unable to get satisfaction from private matrimonial agencies, authorities took matters into their own hands and began to set up municipal matchmakers.

The Japanese are attempting to stave off a demographic imbalance of frightening proportions. A 2009 article in the Independent says:

If current trends continue to 2100, the number of Japanese will have halved and many vibrant cities will be ghost towns haunted only by the elderly because the country has the longest life expectancy on the planet. This estimate is based on the 1997 fertility rate of 1.39 children per woman—well below the 2.1 replacement level that a country needs to keep the population from falling.1

Despite the severity of the problem, Japan has so far rejected what seems like an obvious answer: allowing mass immigration. According to some observers, the refusal to entertain this solution derives from a commitment to the “racial ‘purity’ of a population in which foreigners account for only 1 percent.”2 To be sure, the United States waxes and wanes in its enthusiasm for immigration and, as we have seen, even the famously liberal Nordic states are experiencing problems with assimilation. Nonetheless, Japan stands at the extreme end of the continuum. The United Nations claims Japan needs six hundred thousand immigrants a year, but in 2009, Japan accepted only thirty-six refugees and tightened its restrictions on entering the country.3

In almost all of the countries that have experienced growth in the proportion of accordion families, the subject of delayed adulthood sparked diatribes about immigrants. What is the connection? Native-born Europeans understand that one consequence of their children’s long stay in the household is that they are not marrying and not producing the next generation. As a consequence, the next generation of these high-immigration, low-fertility societies is far more diverse than it ever has been. The prospect of a society that looks different is not always welcome.

Marina Tessiore knows this problem from the inside:

Yes, I think [people having fewer children is] a problem, also because immigrant people don’t stop [having children], and so one day they will be more than us. But I understand that nowadays having many children is hard.

Now 5.8 percent of Italy’s population is composed of the foreign-born, most of whom have flocked to the region where the Tessiore family lives, the most prosperous part of the country. Here, immigrants account for nearly 8 percent of the total population.4 When children come out to play in the parks, it is the sons and daughters of the immigrants that Marina sees. She has only one grandchild at an age when her mother had a dozen. Her counterparts in Spain would see much the same on the playground. In 2008, one in five Spanish births were to foreign mothers (20.7 percent) and increased 15 percent in just one year.5

In countries that do admit immigrants (whether legally or illegally), the newcomers often have children at a much earlier age. Both Spain and Italy have below “replacement level” fertility among the native-born6 but much higher birth rates among the immigrant communities in their midst. Immigrant mothers have more children, and among immigrant families completed family size typically outstrips that of the native born. The resulting gap can produce new and acute anxieties about who owns the national culture.

Japanese parents are keenly aware of the problem of low birth rates, not only in their own families but for the society at large. Kana, whom we met in chapter 4, lives with her thirty-one-year-old daughter. She complains about how women are less likely to consider starting a family when society won’t help them with the expense of doing so. From Kana’s perspective, the problem of declining fertility is a matter of “basic human rights,” meaning the rights women should have to pursue careers. If this is not supported by society at large, millions of women will simply “opt out”:

In a society [that doesn’t respect these rights,] they do not provide sufficient day care. Society does not provide an environment where women can bring up their children. So this is revenge from women. They are saying they cannot give birth to children in a society like this. It can be seen as women rising in revolt.

The cost for delivery is also expensive now. It costs several hundred thousands of yen [$4,500 to $5,400] per delivery. They pay for it by themselves and get reimbursed about 300,000 yen [approximately $2,700] afterwards. Still, it costs them 300,000 yen to deliver. Thus the women think if it costs that much, they will not bother. And the monthly checkup costs about 10,000 to 20,000 yen [approximately $90 to $180]. They wouldn’t want to spend that much money.

But expense is only part of the equation for Kana. She sees the birth dearth as a consequence of a malaise or society-wide depression that is leaving women without the motivation to marry or raise a family. As she sees it: “The environment in which they grew up is not something that has made them feel happy about being born. They are not motivated to have children in the first place, and there are not appropriate conditions for that, either.” Kana’s lament focuses on the long-term consequences of the economic stagnation that has plagued Japan for more than a decade. But it is also an uneasy recognition that women have more options in the modern world and that having a family is no longer the unqualified, paramount objective.

There is, of course, a relationship between the growth of the accordion family and the low fertility rates of the native born: the longer young people stay in their parents’ home, the longer they delay marriage and childbirth. Thirty-five-year-old newlyweds immediately confront the biological alarm clock: if they have children at all, they might be able to have only one.

The United States would resemble Japan more closely in its overall fertility rate if we did not have a significant population of newcomers who have comparatively large families. In the next fifty years, the populations of the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Bulgaria, Estonia, and the European Union as a whole will all drop anywhere from 5 to 30 percent. In the United States, though, the population will grow by 25 percent. Accordingly, the Census Bureau projects the population will increase 50 percent in the next fifty years and 100 percent in the next hundred years.7 But where will this population come from and who will contribute to it? New evidence suggests that the native born in this country are less inclined to have children or at least to have them at a young age. More and more American women are either delaying having children or opting out entirely. The trend seems to prevail across all class, education, income, and ethnic groups.8 Nearly one in five American women in their forties is childless, compared with only one in ten in 1971.9

Although politicians riding the anti-immigrant bandwagon in the United States are not likely to admit it, it is the fertility rates of immigrants that will save us from the fate that befalls Japan. Mexican immigrants, in particular, are responsible for keeping our population growth above the replacement level. Newcomers will help the country by creating a larger, younger, and healthier workforce (assuming, of course, that these children of immigrants decide to remain in the United States). In 2006, the U.S. fertility rate hit its highest level since 1971. This means we are producing enough young people to replace and support our aging workers without going beyond the population size that can be supported by current rates of national taxation.10

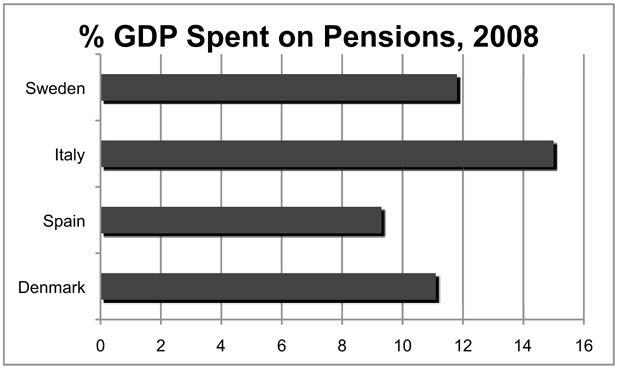

State pensions in most countries, the United States included, depend on the contributions of several active taxpaying workers for every retiree drawing support out of the system. While Europe currently has four people of working age for every older citizen, it will have only two workers per older citizen by 2050. Given current policies, the pension and long-term health care costs associated with an aging population will lead to significant increases in public spending in most EU member states over the next fifty years.

Source: Eurostat, Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg.

When the native-born generations start to “dry up,” a trend prompted in part by the growth of accordion families, the base of the pyramid becomes too thin. There are only a few solutions: invite immigrants in to fill the missing space, tax everyone else at much higher rates, or slash the safety net.11 Of course, what seems demographically plausible can be politically impossible. What would the consequences be if middle-class Americans—of all colors—see a sharp drop in their fertility while poorer families with less education continue to have large families? The answer is clear: we would be at risk for a less productive country unless we quickly invested in public education, enough to insure that future generations were high in human capital. Sadly, particularly in states like California, we seem to be headed in the opposite direction.12

Waves of anti-immigrant sentiment—whether bubbling up from below or stoked by politicians from above—seem almost inevitably to follow financial downturns, labor-market competition, or the political battles that attend the cost of the national safety net. Despite the fact that immigrants have helped stoke economic growth in the Southwestern states, Arizona has led the way on this unfortunate front with legislation authorizing the police to stop anyone who might appear to be an illegal immigrant and demand their papers. Calls have been heard to repeal the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment that grant citizenship to children of illegal immigrants born on American soil. Proponents of the repeal have, among other things, touted it as an anti-terror measure, necessary to address the threat of so-called “terror babies.”

Europeans have experienced waves of agitation along the same lines. When a population ages, an already overtaxed welfare system may just collapse because the active workers needed to fuel it are too few in number. Demands for pension reform often follow because the existing system of benefits is too costly. Yet woe be unto the politician who touches this third rail of social policy. A spate of strikes and riots spread through Greece, Germany, Italy, France, Portugal, Spain, and Austria in 2010 as changes in pension benefits, civil-service wages, and the like were proposed to deal with their debt crises. These reforms are rarely popular.

Weakened labor markets, some reflecting the increasing international competition that comes with globalization, mix with the toxic trail of the Great Recession, to produce deep anxieties about the fate of young adults, working-age parents, public-sector workers absorbing cuts in state budgets, and retirees worried about pension reductions. Students in England marched on Parliament in November 2010 in protest against tuition increases prompted by government spending cuts that were, in turn, a conservative effort to reduce deficit spending; French workers have gone on strike in response to government plans to raise the retirement age; Greeks have been on the picket lines objecting to reductions in public-sector employment. These domestic policy debates are unfolding in the context of widespread economic distress not only in the developed nations but in developing countries sending thousands of migrants over the borders in search of whatever work they can find.

Accordion families are growing in number against this backdrop. They see how the younger generation is faltering in the labor market, and they look around to see who might be to blame. Their instrumental concerns—how will my son finish his education, my daughter find a decent job, my mother afford to retire, my father pay for his medicine?—mix with cultural fears that the country is being overrun by strangers who will change its character.

Laura Fuentes has seen her sons devote many years to piling up educational qualifications. Their friends have gone down the same path. Their university years have been worthwhile in their own right, but have they paid off? Not exactly. Jobs are not plentiful even for the well-educated. The available jobs don’t require a high skill level or long incubation in the higher-education system. And so those jobs now tend to go to the foreign born, Laura says, adding:

I think … there are not well-paid jobs in Spain for the people, as [highly] qualified as they are. Many students have gone to the university, they have done many courses, and they end up working [in anything]. Then there is a lack of plumbers and manual workers. There are enough jobs like that, and they are occupied by immigrants. But we have a model of the ideal job, and it is very [hard to accept] that someone with a degree, courses, languages cannot find the kind of jobs they would have found in the past. Supposedly, if you were well-educated, you would get a good job with a little effort. And I think that [the situation now] is scary. I think there is also a problem of integration in the sense that there are many immigrants. For younger people, who are eighteen or twenty, it is becoming more difficult.

Why pursue all these credentials if young Italians or Spaniards cannot get work? This is a question many Europeans are asking themselves, as are the Japanese. It is not a simple matter to downsize expectations and ambitions, particularly when the possibility of upward mobility is of such recent vintage. Legions of farmers and factory workers who wanted something better for their children and grandchildren pushed them to go to university—a path they could never have taken themselves. Confronting the possibility that there is no longer a pot of gold at the end of that rainbow has been a monumental disappointment. A change of this magnitude leads ordinary people to dwell on unfair competition, the diminishing control over the fate of their nations. It does not create a favorable context for immigrant assimilation. Laura’s son knows firsthand how these mobility ambitions were fueled and how hard it is to let go of them as the opportunities decline:

Our parents could not study, [so] they have always obliged us to do so. And so even if you [did not want to], you spent ten years [getting] a degree. You still do it. Whereas before that wouldn’t have happened because they couldn’t pay for you [and it was financially impossible]. Either you were really good and made the effort or.… Well, there were also many people who didn’t have the means, and so they couldn’t [go any further in school].

Now everybody has to [get] a degree, and of course there are not enough jobs for everybody. We are also forgetting other things. You can’t be spending ten years [getting] a degree, just because you have to be a graduate, when perhaps you may like more a different path. I think there it is [the main cause of the problem with qualified jobs].

When the arc of underemployment intersects the growing presence of immigrants, the two issues can fuse despite being, in some sense, distinct. Blocking immigrants will do nothing to change the depth of frustation among the high-skilled native born. We can send every illegal Mexican back across the border with Arizona, but this will not create new jobs for physicists or English-lit majors.

Laura can see that tensions of this kind are building in Spain, but the national conversation is often eliptical, focusing more on the tensions that arise from a clash of cultures than on the economic dynamics that promote immigration. “There are many Arabs in Fuenlabrada, many Muslims,” she explains, “young people who envy the way you live because there is a big difference in the life standard, in how they live and how we live.” Laura is uncomfortable with the underlying racial tension; it is not a healthy development for Spain. She counsels her brother, who “doesn’t want anything to do with [Muslim immigrants],” to pursue his education as a way to “see that everybody is the same.” But at the same time, she is skeptical of her capacity to persuade him.

Our European and Japanese counterparts weigh the economic imperative to bring immigrants in against the cultural change that their presence provokes. They worry about whether their country will be recognizable if the native born stop having kids and immigrants continue to have large families. The wealthy countries of the European North have less historical experience with immigration and a far more generous welfare state to assist the newcomers in their midst. Yet in recent years, as incidents of political violence (including the assassination of public officials by Muslim extremists) have increased, Scandinavian citizens have also become more wary of the newcomers.

Conservatives see in the immigrants a permanent foreign presence that will never assimilate and should not be given a chance. Immigration should be shut off, closed down; those already present, sent home. Liberals in the Nordic countries are more tolerant of immigrants, but the appreciation for multiculturalism that is a hallmark of the Left and center in the United States is less conspicuous in Europe, hence the policy emphasis has drifted toward increasing educational opportunities that will speed assimilation: language classes, preschool for immigrant children, and ordinances that forbid particular kinds of dress that marks Muslim women by obscuring their faces. Liberals worry out loud that the generosity of the welfare state has promoted social segregation and the growth of a permanent immigrant underclass.

Henrik, the schoolteacher from Copenhagen, has seen the student body change from predominantly native-born Danes to mostly immigrants:

In this area, there used to be only Danes, but each time there is a war in Bosnia or Somalia or Iraq or Iran … there is an inflow of people. It very much depends on the wars. There are a lot of Palestinians and Bosnians and Afghans, because there are also wars there. People come from all the places where the world is on fire.

In Denmark, [we have taken] a very gentle approach toward immigrants that enter the country; there hasn’t been very many demands. You have given them a service, but you haven’t gotten anything in return. I think there is more focus on that aspect now. Rather than just giving them some sort of pacifying welfare allowance, they should be given a job as quickly as possible, and [we should] teach them to provide for themselves and give them some responsibilities rather than just making them passive. There are a lot of immigrants in this area, and people are afraid it will turn into a ghetto. There has been made [an] attempt to start some activities, but then maybe 300,000 [Danish kroner are] spent [on] some sort of project; this doesn’t change anything. It is a long process.

Hans, the MP for the moderate party in Sweden, also made a connection between immigrant assimilation and unemployment by pointing out the relationship between the structural location of immigrants in the economy and the culture they develop. He laments the way in which a “combination of under-the-table work and social welfare becomes accepted. This has even more serious consequences if you’re born abroad. A child who grows up with virtually no one in their surroundings with a normally paid job eventually gets a totally screwed up idea of how things should be.”

Pym Fortuyn, a Dutch politician who trained as a sociologist, articulated these fears in an attack on Islam as a “backward culture” and advocated closing Dutch borders to Muslim immigrants. Fortuyn was assassinated during the 2002 Dutch national election,13 but his campaign clearly had its effect. In his country, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy, staunch opponents of immigration, pushed through legislation that restricts asylum admissions, welfare payments, and citizenship and residency permits for reasons of family unification. Those under twenty-five who marry foreigners no longer have the right to bring their spouses into the country.14

This reaction isn’t fully explained by tensions in the labor market, for the Netherlands has weathered the challenges of globalization relatively well, as when compared to Spain or Italy. There is virtually no evidence of accordion families in their midst precisely because their youth can still find a place in the labor market and have ample state support for residential independence. Instead, as is the case elsewhere in Scandinavia, they are witnessing a profoundly reactionary rejection of multiculturalism. In a country where, as the Swedish sociologist Åke Daun puts it, “people like being like each other,” there is evidence of extreme exhaustion with immigration.

Journalist Christopher Caldwell writes:

Swedes tell pollsters they want no more asylum-seekers. (A common complaint is that prospective arrivals have figured out how to “game” the rules of asylum applications and that the best way to render one’s story unchallengeable under the law is to destroy one’s identity papers.) A very low rate of mixed marriage is an indication that Swedes may not have been crazy about this immigration in the first place.15

Given the problems in labor markets outside the Nordic sphere, the anti-immigrant movement can be understood as a reaction to economic crisis. The right wing in Italy has pounced on these woes to stir up racial tension over the African migrants landing on their shores. The Northern League launched “Operation White Christmas” in November 2009 to scrutinize the papers of the entirety of one community’s foreign population. Those whose residence permits had expired six or more months before and could not prove that they had attempted to renew them were kicked out of the town (and, presumably, the country). The Northern League member and councilor in charge of security for the town (which is an hour’s drive from Milan), Claudio Abiendi, commented on the timing of the policy to La Repubblica newspaper: “For me Christmas isn’t the holiday of hospitality, but rather that of the Christian tradition and of our identity.”16

Even in the more prosperous countries of Western Europe, the problems attending assimilation are sparking unnerving levels of ethnocentrism and cultural conflict. In November 2010, a prominent member of the German central bank, Thilo Sarrazin, published a book proclaiming the inferiority of Muslim migrants and stoking fears that the country will be overrun by an alien population. The New York Times’s coverage of this story reminded many readers of the last time Germans focused their ire on a despised ethnic group with the headline “With Words on Muslims, Opening a Door Long Shut”:

Mr. Sarrazin’s latest blunt assessment came in the form of his book, “Germany Does Away With Itself,” which was released in August and provoked a heated national debate that has still not cooled.…

In a population of about 82 million, there are about four million Muslims (a number he said he calculated partly by looking at census figures for families with lots of children. Big families must be Muslim, he concluded). Within 80 years, he said, Muslims will make up a majority in Germany.

Second, Mr. Sarrazin believes that intelligence is inherited, not nurtured, and since Muslims are less intelligent (his conclusion) than ethnic Germans, the population will be dumbed down (his conclusion).

Third, to solve a growing demographic problem, Germany will require immigrants, but he says that bringing more Muslims into the country will only make matters worse. He says that after examining three indicators—success in education and employment, and welfare dependency—he concluded that Islam is by its nature a drag on individual success.17

Sarrazin’s book has sold more than a million copies.

The Nordic countries have long prided themselves on tolerance and egalitarianism. They were the haven for Jews attempting to escape the Nazi maw during World War II and have opened their doors to migrants from North Africa and Indonesia who are, on average, less educated and certainly less wealthy than the average Dane or Swede. But these countries, too, seem to be questioning the wisdom of this generosity and the advisability of multiculturalism. The change has been so swift and on such a scale that even a country like Sweden is showing signs of strain. Caldwell writes:

Sweden has suddenly become as heavily populated by minorities as any country in Europe. Of 9 million Swedes, roughly 1,080,000 are foreign-born. There are between 800,000 and 900,000 children of immigrants, between 60,000 and 100,000 illegal immigrants, and 40,000 more asylum-seekers awaiting clearance. The percentage of foreign-born is roughly equivalent to the highest percentage of immigrants the United States ever had in its history (on the eve of World War I). But there are two big differences. First is that, given the age distribution of the native and foreign populations, the percentage of immigrants’ offspring will skyrocket in the next generation, even if not a single new immigrant arrives, and even if immigrant fertility rates fall to native-born levels. But second, when America had the same percentage of foreign-born, many had arrived decades before, and were largely assimilated.18

Mauricio Rojas has emerged as an important voice in Sweden’s small, free-market Liberal People’s Party. A professor of economic history at the University of Lund, Rojas has raised some issues unsettling to those long accustomed to Sweden’s laissez faire culture. In 2004, he completed a nationwide study that showed 136 areas where labor-market participation was under 60 percent—and he wants to remove certain of the subsidies that make such conditions possible. “No one is going to live here without working,” he said. “I told immigrant groups, ‘If we come to power, seven o’clock Monday morning, it’s off to work.’ His Liberal party also urged Swedish-language tests for foreigners.”19 Rojas’s sentiments are shared, increasingly, throughout the Nordic countries. But they still come as a shock to those accustomed to the old Scandinavia, where legislatures rarely imposed rules on inhabitants that would be regarded as intrusive or harsh. The temperature of the debate is alarming to some, including those who openly acknowledge the need for immigrants even as they also recognize the difficulty of integrating them.

Greta, the Danish woman we met in chapter 4, says: “We have to be careful not to throw people out [of the country] ’cause we need them, too. I don’t think we should receive more immigrants, but we have to treat the ones we have well. I think you should treat all people kind. If all this violence carries on, then in a few years it will become extremely awful to live here [in Denmark].”

Greta believes that Danes should provide for immigrants, but she remains wary of them. When violent crime intrudes into her world, they are the first people she thinks about: “It may be the people who come to Denmark. It isn’t that we should blame the dark; we shouldn’t. But two-thirds of the criminals are immigrants; but we [Danes] aren’t free of blame either.”

Unlike Americans, who tend to see the integration of immigrants into American culture as the job of immigrants themselves, the Scandinavians understand it primarily as the role of the government. Greta sees it as a state obligation to provide for immigrants while they are in Denmark and to arrange for them to depart. “When they live [in Denmark], they don’t have the capacity to save money,” she says. “So the state has to give them money so then [they] can manage when they go back.”

Sven is sixty-two years old and has been divorced for fifteen years. He is a senior lecturer in Italian studies at the university in Göteborg and has lived there for about nine years. Sven very much dedicates himself to his work; when he is not lecturing, he works as a translator and has his own translation company. Like Greta, Sven does not blame immigrants for the failure to integrate, nor does he think it is entirely their job to do so. All roads lead to the state:

There are obviously very many immigrants here in Sweden, for better or for worse, and the sad thing is that the authorities have not managed to see to it that most immigrants get jobs and get an education, et cetera, et cetera. I argue that the Swedish authorities have failed at integrating immigrants and making sure their children get a proper education and schooling, too, for that matter. And that means then that there is a large group of immigrants in Sweden, both immigrants and their children, which simply have not adapted to Swedish conditions.

I have seen, living here in Göteborg, how gangs are formed, juvenile gangs with immigrant boys and maybe immigrant girls. And I remember from my time in Malmö and Lund and such [that] Swedes don’t behave that way.

This whole giant, complex issue, it is a big problem that has not been solved, and it needs to be solved in the future in order not to continue to cause conflicts, racial conflicts.

We have close to 15 percent of the population now immigrants or children of immigrants, and I think no European country has such a high percentage. I believe England has about 10 percent, for example.

In recent years, as incidents of political violence have increased, Scandinavian citizens have become more wary of the newcomers in their midst. It’s not that they are opposed to immigration per se. What they want to end is the enclave phenomenon: the segregation of immigrants into their own neighborhoods, the failure of second-generation children to learn Swedish or Danish, and the lapsing into the arms of the welfare state that seems to be the fate of many immigrants barred from the formal labor market.

The cultural distance between the socially liberal societies of the Nordic countries and the conservative, traditional communities from which so many Muslim immigrants in Europe come does not make the integration task a simple matter, even in a tolerant state.20

Camitta Kiersted grew up in a small town south of Aarhus, and she and her boyfriend now live together in a nearby suburb. She has a university degree in anthropology and European studies, and is currently unemployed. When asked what she thinks the biggest social problem is in Denmark today, she points to immigration, partly because of the conservative attitudes of the newcomers, but even more so because of what their presence brings out in her fellow Danes. According to her, it’s not a pretty picture:

The public debate about immigrants [is a real problem]. I think [the] debate might go completely off track as it did … in Paris. There are forces inside the Muslim world that are really anti-democratic, I mean crazy. And that shouldn’t happen without notice being taken, there must be done something about this.

On the other side in this debate, Denmark is totally way out. Instead of asking people what they would like to do, [the authorities] put up demands that should be met. This is a very mild example. I mean [they are] giving [immigrants so little that] they can hardly live.

Having experienced bouts of unemployment, Camitta is familiar with what it feels like to be on the receiving end of welfare services in Denmark. As the country has become more conservative, wary of the long-term unemployed, the native born have felt that sharper end of the stick. Yet this is mild by comparison to what immigrants experience when they line up for welfare benefits.21 Camitta shares:

What happens to me is nothing compared to what immigrants go through. The way the unemployment service [responds in] their letters is very threatening, telling you what will happen if you don’t show up to your appointments. The threats are lurking under the surface all the time.

Only it is worse [for immigrants who are under] suspicion all the time. The [unemployment insurance] is almost impossible to survive on. And at the same time, you have to be available for the labor market. This is people at the bottom of society; these people have to take all kinds of hard jobs at late hours. Nobody asks the person what the person would like to do.

I remember a few years ago when there was a lack of doctors in Odense. A meeting was held where everybody [among the immigrant population] who was a doctor was asked to come and get help so that they could be integrated in the Danish medical force. People were surprised how many doctors showed up. It just surprises me that you don’t register the skills of people when they enter the country. You just place everyone in the same lowest-level language class and leave them on their own to become taxi drivers, even though they might be doctors or engineers. It is a complete wrong way to go about things.

Katja, twenty-five, lives in an Aarhus apartment with seven other students. She has recently finished four years of training at a teachers college and has lined up her first teaching job. Katja is also a musician and plays in her own band. She shares with Camitta the sense that the immigration debate is having a corrosive impact on Danish society:

At the moment, immigrants are very much classified as being ethnically different from us. I think this prevents people to look upon other people as human beings. We just look at people and say, you are an Arab; we can’t use you for anything. We still have the problem [in Denmark] that you can’t get a job if your name is Muhammad.

Social conflict runs in both directions. The native born eye the immigrants with suspicion and, in Katja’s view, the second generation—the children of immigrants—can feel the loathing and respond in kind:

It has very much been discussed how we can integrate them into the labor market. They started liking [Danish] society and want to participate and be good citizens and be a part of society. If you don’t take part in society and are spit on in the face, then of course you don’t desire to contribute to society and you just think that other people are assholes.

Incendiary attitudes of this kind led to a long-simmering spate of riots in the banlieu—the Parisian suburbs—as segregated youth of North African descent lashed out throughout France, burning cars, trashing shops, and marauding in the streets and subways. Banished to the outskirts of the city, lacking any means of fitting in, whether in school or the work world, the children of Algerian and Moroccan immigrants let it be known that they had had enough. In Katja’s view, Aarhus may not be far behind. Denmark is growing its own segregated, malcontent second generation, as well as an ugly form of Danish nationalism that has no space for diversity.

Katja is a schoolteacher, and she sees that new generation up close. She cannot escape the sense that they are growing up in a different world than the one in which she did. Their home life is, she thinks, disorderly and rough, which means they start out with too many handicaps to be able to blend seamlessly into the Danish world:

In the elementary school, there [have also] been problems. Here in Aarhus, [in immigrant ghetto schools,] they have relied on the educational strategy they used to practice in the past, where focus was constantly directed at the things the pupils can’t do. “You don’t know how to spell, learn how to.” And these [immigrant] kids don’t have a lot of skills, and they really have a lot of trouble, they aren’t [properly] fed. They really get crappy food [at home], so they can’t concentrate. They have thirteen siblings and parents that are mentally unbalanced and have post-traumatic stress syndrome.

And this is where something should be done, there should be more money given to these schools to make sure that [the kids] get fed properly and so they can stay awake, so that they don’t fall asleep or get hyper. A lot of kids get hyper because they get too much sugar. The methods of teaching should be rethought. How could the schools raise the self-esteem of the pupils so the pupils won’t end up hating Danes and authorities? So they don’t become angry young people that go out and get into trouble like all other people with low self-esteem do.

[I]n general, in this process of globalization, we have to look upon people with other cultures in a more sophisticated manner. That they have other beliefs. We have relics from the age of colonization, about how other races are inferior. It said in the books of history that they were monkeys, the other [races].

These sentiments about the lack of immigrant integration are echoed by some in the Southern European countries as well. Stefano Astore, twenty-six, would agree with Camitta that the biggest problem with immigrants has little to do with their behavior and everything to do with how fellow Italians react to the presence of anyone who is a little different. Stefano lives near Milan with his parents and sister. He did not go to university, but he has worked steadily since he left school at the age of sixteen. Even so, he cannot afford to live on his own. In some settings, that might lead him to blame immigrants for his economic difficulties. Instead, he blames his fellow countrymen for their ignorance: “Immigration is another problem because people become intolerant toward other people, and there’s a lot of racism, especially among those people that don’t have enough culture to understand that the melting pot is a richness for society.”

The dominant tone of the debate in Spain seems to belong to those who believe that the immigrants are a permanent foreign presence that will never assimilate and should not be given a chance. Take Elena, the married mother of three, whose twenty-five-year-old son lives at home with her in Madrid. Elena thinks of herself as a liberal. After all, one of her daughters is a social worker employed by the Refugee Department of the Red Cross. Still, Elena believes that “too many people are coming in, and it is a problem [politicians] have to tackle because it is going beyond their control.” Others are less harsh in their views but still express fear of immigrants and are not sure exactly where to place the blame for what they perceive as their bad behavior. Some blame the immigrants themselves, while others blame the state. Most seem to blame a combination of the two.

Migration has long been a feature of the Mediterranean world, but the emergence of the European Union accelerated the trends. As long as the economies were growing and the progression of native-born youth into the labor market was smooth, the absorption of hundreds of thousands of culturally distinctive families was a minor matter. The eruption of budget deficits, rising unemployment, and housing shortages (relative to the demand), created tensions that exacerbated underlying distrust of the newcomers and fueled the ascendance of far-right political parties that had long simmered on the sidelines.

These tensions have emerged in countries with a pronounced trend toward accordion families (like Spain and Italy) and in societies where youth independence remains the norm. Japan is so antagonistic toward the idea of immigration that it has almost none and hence is a rapidly aging society, in which birth rates have declined sharply, and no one is there to fill in the gaps as immigrants have in the United States or Western Europe. Japan escapes the rising anger directed at “the other,” only to turn the same kind of frustration toward its own youth. In all of these instances, globalization has set off problems of intergenerational downward mobility, stagnation in labor markets, and fiscal pressures that threaten the safety net. Where immigrants are available to shoulder some of the blame, they find themselves the target of reactionary politics or cultural frustration. There is no direct line between the accordion family and immigration, but the dismay that follows blocked opportunity and disappointment lands on the outsider, whether defined as a Japanese freeter or a Moroccan youth unwelcome in Denmark.