Chapter

5

“A-HUNTING WE WILL GO!”

MORNING came to Saturday Cove, and with it the heaviest fog of the summer. Sally, peering through the side lights of the front door, could scarcely make out the tulip tree by the gate.

David handed her a set of oilskins. “We’re meeting Poke at the Historical Society at nine-thirty. Let’s go.”

Through a silent world of white they walked in to town. The fragrance of bayberry and spruce was everywhere heavy about them. Now and then a crystal drop gathered and splashed downward through the branches. Sometime in the night the bay and its familiar islands had vanished. From Harbor Road at the head of the town they could see only the ghostly oneness of sea and sky and land. Over it all moaned the dismal voice of the foghorn on Big Fox Island.

Sally mimicked it. “OOOOOOO-ooo, OOOOOOO-ooo. Spooky old thing.”

“It’s a thick fog, all right,” said David. “You could slice it with a bread knife.”

“But it’s a perfect day to read through the old records. I just know we’re going to find out how long Jonathan was gone that night the British came. I feel it in my bones.” Sally ducked, laughing, as a bluejay took flight from a pine tree and showered them with a cascade of silver drops.

“Let’s hope so,” said David. “But even if we do find out, we won’t be doing any rowing today.”

Sally stared at her brother. “But we have to. We haven’t much time. Poke said so,” she declared as if that settled it.

David shook his head. “We’ll have to wait till the fog lifts.”

“But you’ve gone out in a fog before.”

“Maybe in a light fog,” he agreed. “But not in a pea-soup fog like this. The only times most of us don’t haul are in a real good wind, or in a pea-souper.”

Sally squinted up at the white sky. There was not a glimmer of sun. “Then it’s got to burn off,” she said fiercely. “Because in a few days that Roddie McNeill will own Little Fox and Blueberry, both of them, and then where’ll we be?”

“No worse off than we were before, probably. There’s Poke, coming out of the drugstore.”

Poke greeted them, his dark brows drawn together into a puzzled frown. “I was drinking a milk shake while waiting for you two,” he told them, “when who should come in but Foggy Dennett and Willis Greenlaw.”

“What’s wrong with that?” asked David.

“There’s nothing wrong, really, except what Willis said, or possibly the way he said it.”

“Well, what did he say?” Sally demanded.

“He said, ‘Where’s Dave? Now it’s a pea-soup fog, your friend ought to be out doing a little extra hauling for himself.’ ”

David was relieved. “He was only kidding, Poke. The men do a lot of teasing. Willis knows I wouldn’t go haul in a fog like this.”

“Probably.” Poke brightened as they approached the foursquare colonial building that housed Saturday Cove’s Historical Society, and the incident was quickly forgotten.

Sally’s spirits were high. Elated, she jumped the cracks in the sidewalk. “Just think,” she whispered with a superior glance at the passers-by, “we’re about to go hunting for a buried treasure, and not a soul in town knows it.”

“Except Roddie McNeill,” David reminded her.

“And Uncle Charlie,” Poke added in the interests of accuracy.

Together, they entered the dim hall. Mira Piper, the custodian, glanced up from her desk. Her welcome was so genuine that Poke gave her one of his rare, warm smiles.

“We’re looking for material on the Revolutionary history of Saturday Cove,” he explained.

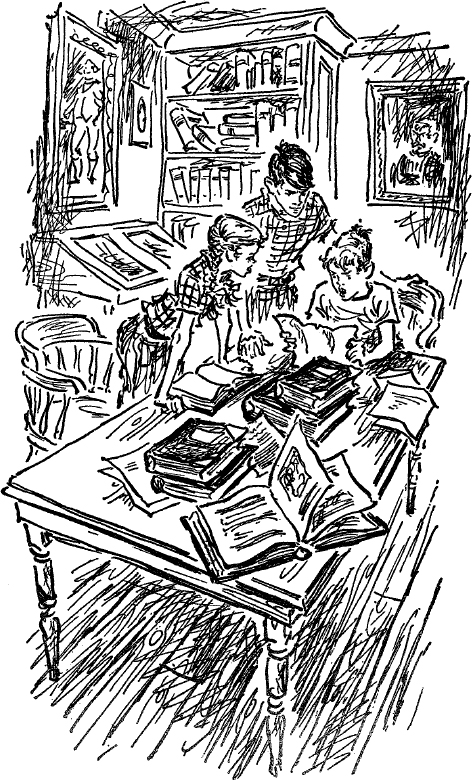

“Wonderful, Elijah!” The little woman nodded appreciatively. “I love to see our young people take an interest in the town history. Now you and Sally and David just follow me.” Like a sparrow she fluttered ahead of them into a reading room. Darting in and out among the files, she soon had the long table piled with volumes and records.

“We’ll take good care of everything, Miss Piper,” David promised.

“And our hands are nice and clean,” Sally put in.

Mira Piper laughed. “I’d already glanced at them,” she confessed. “I’ve always trusted children with these precious old things,” she told them, “and I’ve never once been disappointed. When you’re through looking at them just leave them on this table. I’ll put them away.” Then, with a quick nod, away flew Mira Piper, back to her desk, leaving behind her a delicate fragrance of roses.

All three of them sniffed contentedly for a moment. Then they settled down to work, each with a heavy book. For some time there was silence.

“Aha!” said Poke suddenly.

Sally and David looked up. “What?” they asked, both at once.

“It says here,” whispered Poke earnestly, “that masses of soft limestone can be found in this area along with the more common red sandstone and greenstone and granite.”

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, Poke,” David broke in. “What are you reading?”

Poke looked seriously at the cover. “Lithographs of the Penobscot Bay Area,” he read.

“What does that have to do with the Blake treasure?”

“One never knows,” rumbled Poke. “Interesting fact, though, isn’t it?” Greedily, he resumed his reading.

David, with a tolerant shake of his head, returned to the mass of material piled in front of them.

The long minutes ticked loudly past. Sally read on about the early days of Saturday Cove — its first settlement by John Blake on the island at the head of the inlet, the cutting of timber on the mainland, the visits of the Indians who were peaceful during this period, the slow growth of the village along its present Main Street.

Outside, the foghorn moaned without ceasing. On Blake’s Island the fog would be swirling up the path and about the old house. Again, by the flickering glimmer of the candle, she seemed to see Jonathan’s faded chart. Sharply, she smelled again the cold dampness of the buttery and felt the shadows of the ages reaching out of the silence.

Softly closing her book, Sally tiptoed away from the table and inspected the case of Indian and colonial relics that stood against the wall. Arrowheads. Grape-shot. Militia buttons. Her eyes fell on one button, dull and flat and as large as a silver dollar. A card beneath it bore the legend, “Pewter. Revolutionary War Period. Rare. Found on Blake’s Island.” Sally stared at it, reflecting that it might long ago have graced the coat of John Blake, American patriot. Then, impatiently, she hurried back to the table. David’s sunburned face and Poke’s pale one were still bent in identical attitudes. David had just started on the contents of a manila envelope filled with faded papers.

“This might take days,” Sally told herself. Discouraged, she sat down again and leafed through another book.

Then David whispered, “Poke! Sally! I think I’ve found something.” For a moment he gazed at the paper he held in his hand. Then he glanced up at them. “This is a letter written in 1779 by John Blake to a relative living in Salem.”

“Oh, read it!” cried Sally, and Poke leaned forward with interest.

David cleared his throat. “Dear Joel, Our regiment, which was let go home for the mowing, is again to be mustered and I am to leave this day. I beg of you, Cousin, will you remember that my good wife, Sally, and our children must fend alone for themselves on this island whilst I am gone, and that if the worst should happen to me, I pray that you, my kinfolk, will have a thought for them.”

Sally caught her breath. “Oh, poor John Blake.”

“He came back safely,” David reminded her. “Now listen to this, We are free men fighting on free soil to hold what we have against tyranny. I have faith that I shall return right soon to see to the harvest, and to another important matter. . . .”

“I wonder . . . .” Poke mused.

“Yet again last night we had considerable trouble from the raiders.”

“This is it!” Poke broke in.

“They were off a British frigate of about fifty tons which before sunset came in with the tide. Several of these robbers laid hold on me as I was employed in the barn. They shot my oxen and killed two of my lambs which they quartered and carried aboard their barge. Others of the company entered my house and brought away two muskets of great value.”

“They lived by their muskets then,” Poke broke in.

“. . . two firkins of butter, and the roast of venison made ready for the evening meal. They would likewise have plundered the house of other articles of value, but that my brave Sally caused these to be taken away to a place of safety by our son, Jonathan.

“This very night there came up a wind of such force that we were soon rid of the Lobster-backs and did much rejoice in the safe return after two hours of our eldest son. . . .”

David laid down the letter and looked up, his eyes shining.

Poke released a long breath. “Question: How long was Jonathan gone? Answer: Two hours. Question: Where did he go? Answer: To whichever island he could reach and return from in that time.”

“Bucking a head wind one way,” David reminded them.

“And with time out to hide the treasure,” Poke added.

But Sally was not satisfied. “If all this is true, then I don’t see why they didn’t go back later on, after the British left, and dig the treasure up again.”

“Something happened,” Poke stated. “Something that made recovering it right away impossible. John Blake certainly intended to unearth it when he got home from his regiment. Remember, he wrote, I shall return right soon to see to the harvest, and to another important matter. But something had happened, and neither John Blake nor his son, Jonathan, ever recovered the valuables.”

Sally was downcast. “I know what happened,” she said gloomily. “Somebody else dug them up before Jonathan and his father went back for them. That’s what happened.”

David shook his head. “In that case they would have found an empty hole when they went to dig. Then the family story wouldn’t have come down to us the way it did. It would have been the story of a stolen treasure, not a lost one.”

“Could they possibly have forgotten where it was hidden?” Poke then asked.

David thought for a moment. “If they had, wouldn’t that have been part of the story? We never heard that they did any hunting for the treasure, though folks have hunted plenty since then.”

Poke nodded slowly. “That’s right. But for some reason they couldn’t recover it, either before John Blake went away or after he returned. And yet, they kept the hiding place secret, so they must have expected to get the things again sometime.”

Sally, not altogether understanding, looked from one of the boys to the other, content to let them do the reasoning. The old story had begun to come to life. It was taking misty shape from facts long hidden.

Eagerly, David took up the narrative. “If they didn’t recover the treasure in their lifetimes, then the valuables have stayed right where Jonathan hid them the night the British came.”

“But why didn’t Jonathan pass on the secret to his children?” Sally demanded.

“I’ll bet he meant to,” David said softly. “Dad once told me that Jonathan went down with one of his own ships off the coast of Africa while he was still quite young. So perhaps the only clue he ever left was the chart he drew when he was a boy.”

“Only clue,” Poke shook his head. “This case is packed with clues. John’s letter to his relative in Salem tells us how long Jonathan was gone. That, in turn, will tell us which of the islands he rowed to. We know that Jonathan and his father waited their lifetimes for something to happen in order to recover their treasure. And we know that they never recovered it. Something must have happened to the hiding place.” He looked to his friends for help but, carried along on Poke’s enthusiasm, they had nothing new to offer. “If we hunt with our minds are well as our eyes,” he told them, “we may find it. . . .”

Sally leaped to her feet. “Come on! Let’s go out to Blake’s this very minute and start rowing.”

“When you find the island that lies about an hour’s row from Blake’s,” said Poke, “you’ll have your treasure.”

But they went outside into a fog that was, if anything, thicker than ever.

“It’s bound to clear tomorrow,” said Poke, and Sally crossed her fingers.

But the next morning Saturday Cove was fogbound, and the town knew that it was in for a “spell of weather.” For two more days the foghorn on Big Fox Island blew steadily. Automobiles, when they moved at all, crawled half-blind through Main Street with their headlights on. In the Cove the lobster boats lay motionless, at anchor.

“If it gets any thicker,” said David in disgust, “the sea gulls will be walking.”

At first David and Sally railed against the fog. Repeatedly, they peered through the windows to see if, in spite of the weather reports, the fog showed signs of lifting. Neither mentioned the McNeills, nor the deeds to Little Fox and Blueberry Islands. But each knew that the other thought of little else.

To take their minds off the passing of time, David did chores and projects that he never got around to doing in hauling weather, and Sally helped him. Together, they mended the chicken wire. They cleaned the barn. They put up a new tire swing in the loft.

And once each day David, in return, gave Sally a swimming lesson on the foggy beach at Goose Creek. But it was no use. The instant the cold water closed over Sally’s head she scurried out and, to David’s disgust, refused to go in again.

Occasionally Poke came over. Rather indifferently, the three of them did experiments with David’s old chemistry set, or shot for baskets in the barn.

Finally, on the third long day the wind changed. The wind changed into the northeast only to blow up a gale that lashed at the coast in concentrated fury. Silent and defeated, David watched the rain stream blindingly against the windows, watched the elms toss in the wind, listened to the torrents of water gushing from the rainspouts outside. “This means there’ll be plenty of repairs to make on the gear,” he told Sally gloomily.

Then he brought out his twine. Together, he and Sally knitted heads for the lobster traps, thinly content with at least this much of the sea. And by late afternoon the storm had begun to spend itself.

Mrs. Blake said at supper, “This is a williwaw, all right, a real old-fashioned northeaster. But it will begin to move out tomorrow. You’ll see.”

And she was right.

The next morning Sally ran into David’s room. “You can see all the way to the road,” she cried. “It’s still foggy, but you can make out the tulip tree as clear as anything.”

“Then let’s go!” said David. He was eager to tend to his neglected traps, to check his gear for damage done by the storm. But his interest in the Blake treasure had, like Sally’s, mounted with the delay. The traps could wait, as usual, until the afternoon.

Soon after breakfast they were on their way. Fog still shrouded Saturday Cove, but it no longer seemed like a solid wall. Rather, the mist was in motion, swirling and thinning to show weird glimpses of familiar things.

It was good to be in action again. Sally trotted along in silence for a while beside her brother. Then she lifted her head and sang:

“Cape Cod boys they have no sleds,

Heave away! Heave away —!”

And David joined in:

“They slide down dunes on codfish heads,

We are bound for Califor-ni-ay!”

When they reached Harbor Road they met Mira Piper just leaving her little house at the top of the hill.

“Well,” she smiled at them, “aren’t we all up bright and early. Just like Noah’s animals coming out of the ark after their spell of weather.” She walked along beside them, chatting as rapidly as she walked.

She twitters just like a happy robin, thought Sally, liking her.

“Tell me,” said Mira Piper, “do you two young people know the McNeill boy?”

“Not very well, Miss Piper,” said David.

“Not nearly so well as we’d like to,” Sally added wickedly. David nudged her.

“Such a quiet boy. So interested in history. He was in to see me the very day you were. Just think of it, David and Sally,” she smiled, “new to town, and already taking an interest in our history.”

“Think of that!” Sally said to David with special meaning.

“But so lonely,” Mira Piper went on. “Perhaps you two and that nice Elijah Stokes could make friends with the poor boy.”

“Perhaps we could,” said Sally, so sweetly that she received another nudge from her brother.

Then David said quickly, “Miss Piper, did you show Roddie the same old records that you got out for us?”

“Oh, yes. The town history is available to everyone, you know.” They had reached the Historical Society building and Mira Piper paused dreamily in the doorway. “Just think, children. This old house was new at the very same time that the British raided Blake’s Island.” She gave them a bright smile. “Come in again soon and bring the McNeill boy with you. He’s so interested in history, and he seems so lonely.” Then she disappeared inside, hopeful that she had sown the seeds of friendship between the Blake children and Roddie McNeill.

When they were beyond hearing Sally sputtered, “So lonely! And so interested in the Blake treasure!”

“We don’t really know Roddie,” said David. “Maybe he just likes history.”

Sally’s voice was flat. “We know him well enough. We know he likes to show off in boats. And we know he likes to spy on people.”

David grinned. “If you hadn’t been spying, yourself, we’d never have known that.”

“Well, that proves he has our chart, or he would never have bothered to spy on us.” Sally brightened. “Why don’t we just ask him for it?”

David laughed shortly. “Roddie,” he said, pretending a conversation, “if it isn’t too much to ask, would you be so kind as to hand over our chart? Look, Sally, if he found it and kept it in the first place, he wouldn’t give it up now, would he? Especially since he has found out that there really was a treasure.”

Sally shook her head.

“Let’s say he does have the chart. He’s boned up on town history as well. His dad has bought a couple of the islands in question. Well, then, he probably figures it’s every man for himself, and the winner take all.”

“That’s what Mr. McNeill was saying at Uncle Charlie’s antique shop,” Sally remembered. “And he said that a smart operator finds the short cuts or he gets left.”

Unconsciously, they began to walk faster. They reached the docks just as Perce Dennett drove his bait truck out onto Main Street. David raised his hand in greeting, but the man seemed not to see him.

“It’s a good thing this is bait day,” David told Sally. “I was just about flat out of redfish.”

“I wish you didn’t have to haul this afternoon,” Sally complained, not interested in the redfish. “I wish we could row all day.”

“We’ll do what we have time for.”

“If only Poke would go out in a boat,” said Sally with a flash of her old resentment. “Then he and I could row out to all the islands while you’re hauling.”

David agreed with her, but remained silent.

“If only Mother didn’t mind if I rowed alone.”

“You have to learn to swim, first,” David reminded her.

Sally, downcast, said no more.

They stopped at the gear shed only long enough to get the oars. As they passed the bait barrel, David stopped, surprised. “That’s funny. Perce didn’t leave me any bait.”

He looked into the barrels grouped by the other shacks. Each was filled to the brim with briney, salted redfish.

“He must have forgotten you,” said Sally.

“He never did before.” Frowning, David followed Sally down the ramp.

Back in the dory again, the motor taking life under his hands, he decided that it didn’t matter if Perce had forgotten him. Willis Greenlaw or Foggy Dennett would lend him enough bait for the day.

The Lobster Boy swung slowly into the cove. A short way out they caught sight of a figure sculling his skiff slowly in toward Fishermen’s Dock.

“There’s Willis coming in from hauling,” said David with relief. He cut back the motor and greeted the lobsterman. “Could you let me have a little bait later on?” he called. “I’m flat out and Perce forgot to leave me any.”

His words hung unanswered on the fog. Without changing expression, Willis Greenlaw continued steadily on his way.

Silently, they stared after him.

Sally said in a puzzled voice, “Maybe he didn’t hear you.”

But David was remembering that Willis had approached Poke in the drugstore a few days before. What was it he had said? “Now it’s a pea-soup fog, your friend, Dave Blake, ought to be out doing a little extra hauling for himself.”

“But what are they worrying about?” David asked himself. “Even if I did haul in a pea-souper, even if I got lost, it wouldn’t hurt them any.”

David glanced at Sally’s anxious face and forced a smile. “Maybe it wasn’t Willis, after all. It’s hard to see in this fog.” But it was Willis, all right. David had seen him clearly when the mist had thinned for a moment. A dark worry began to nag at him.

Then they were put-putting into the fog. Maybe Willis hadn’t heard him. Or maybe his mind had been on something else. David forced his attention back to the task of guiding the dory out of the cove.

“We’ll use the motor as far as Blake’s,” David shouted. “Then we’ll start rowing to Little Fox. Then Blueberry. Because if the McNeills don’t own those islands yet, they soon will.”

Close to the shore of Blake’s, David shut off the motor and checked his watch. “If Little Fox is the right island, we should be there in less than an hour. That would give Jonathan time to hide the things and row back against a head wind.”

David headed the dory for the bell buoy that would serve as a bearing on Little Fox Island beyond. Neither spoke as he pulled easily, steadily at the oars. But both of them had the same thought, Was this the course that young Jonathan had taken, alone and in danger, that windy night so long ago?

Soon the dismal clang, clang, of the buoy grew louder. The red marker became visible beside them, rising and falling on the long swells. Then, very gradually, the outline of Little Fox Island took form beyond the buoy.

Now and then as they rowed on, the muffled sound of a motor came to them and a lobster boat moved into their view and out again. But otherwise this was an unearthly trip. It seemed to David that they were alone in a wet, white world where everyday things did not exist.

When they turned into the sheltered cove of the island, David looked at his watch. “Forty minutes. Sally, Jonathan could have come to Little Fox. He could have hidden the treasure here.”

But Sally did not answer. She sat frozen in the bow, staring at something just beyond.

Not ten yards away lay the Pirate, Roddie McNeill’s boat, her narrow hull gleaming against the gray water.

Then, through the fog, they heard the sounds of a spade striking into rocky island soil.